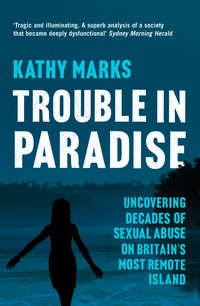

Trouble in Paradise: Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island

Then it was time to move, and that meant up.

Pitcairn, the tip of an extinct volcano, has little flat land. Overshadowing The Landing, as it is known, is a 300-foot cliff, at the top of which Adamstown, the one settlement, crouches on a slender plateau. It is reached via a steeply winding track, aptly called the Hill of Difficulty, which in 2004 was still ferociously rutted and suitable only for quad bikes, the sole vehicles used on the unsealed roads. A dozen quad bikes were parked near the jetty, like a herd of exotic animals congregating around a waterhole. I climbed onto the back of one driven by the island’s New Zealand doctor.

I took the doctor for an islander and he did not enlighten me, apparently enjoying a little game of who’s who. As I tried to draw him into conversation, we passed a pink bulldozer on a hairpin bend; inside it was a dark-haired man with a moustache and swarthy features, who was busily repairing a stretch of road. I did not realise then, but it was Steve Christian—Randy’s father, mayor of Pitcairn, and the principal defendant in the child abuse trials. Steve had not been on the longboat, nor at The Landing. But there he was, watching events from on high and asserting himself as a person of importance as he carried out vital maintenance work completely unconnected with our arrival.

The quad bike laboured uphill, with spectacular views of the bay unfolding beneath us. At the top, the ground suddenly levelled out, and we forked right along the ‘main road’, a dusty red trail that snakes through the village, fringed by a dense tangle of bush—hibiscus, frangipani, banana and coconut palms, pandanus trees, bamboo and towering banyans. Turning down a side lane, we headed back towards the ocean, and after passing a cemetery stopped outside the Government Lodge, the rather grandly named dwelling allocated to the media.

The Lodge, generally occupied by official visitors, was a pre-fabricated four-bedroom house, rather basic, with spartan furnishings. It reminded me of my student days 20 years earlier, and the comparison was fitting, for we six adults, aged from late 20s to late 50s, were about to revert to precisely that kind of communal set-up. I agreed to share a room with Claire Harvey, a reporter with The Australian newspaper. Ewart Barnsley, the Television New Zealand (TVNZ) correspondent, took up residence with his cameraman, Zane Willis. Neil Tweedie, of Britain’s Daily Telegraph, was to have his own room, as would Sue Ingram from Radio New Zealand.

The Lodge was not only our new home, but a workspace. Media interest in the forthcoming trials was intense; TVNZ’s footage would be broadcast around the world, and our syndicated press stories and photographs would be published widely. I was acutely aware that we were all filing for different time zones, and mostly for more than one outlet—in my case, newspapers in the UK and New Zealand. Television, radio and print each had its own demands. I wondered how we would fare, all cooped up together and confronting Pitcairn’s peculiar logistical challenges.

Laptops were quickly arranged on the dining-room table and hooked up to the relatively new internet system. Zane and Ewart set up an editing suite in their bedroom. Satellite phones were lined up on a grassy bank behind the house, antennae pointing optimistically skywards: the island had no landline telephones and mobiles had not functioned since we had left Tahiti. Satphones would be our only means of speaking to anyone in the outside world.

We had brought with us every conceivable piece of technical equipment, as there was no question of getting anything repaired or replaced on Pitcairn. For the other necessities of life, only limited items would be available in the local shop. Packing for the trip had involved trying to envisage every eventuality—and we had only been allowed 20 kilograms of luggage.

After briefly settling in, Claire and I set off to explore. A back lane wound up past the Mission House, usually inhabited by the resident Seventh-day Adventist pastor but temporarily assigned to the three trial judges from New Zealand. The islanders were all Adventists, having converted en masse in the late 19th century. Beyond the Mission House, past a tall mango tree, stood Pitcairn’s newest building: a large, L-shaped prison, elevated on stilts above a dirt yard, with six double cells fronted by a wide wooden deck. The prison, which looked quite attractive, had been built by men who were at risk of becoming its first inmates—no one had wanted to miss out on the work, even in the circumstances.

The lane spat us out in the village, Adamstown, which appeared to be deserted. Scattered along the main road were houses of weatherboard and corrugated iron, somewhat ramshackle-looking; other homes, all single-storey, were found off a jumble of tracks that meandered further up the hillside. Although there was, notwithstanding the steep terrain, quite a bit of space on which to build, people seemed to be living almost on top of each other.

Above the main road was the square, the heart of the community, where a few mainly timber buildings clustered around a patch of roughly laid concrete. The brick Adventist church faced the public hall, with its graceful white verandah; between them were squeezed the pint-sized library and post office. A bench ran along the fourth side.

In front of the hall, which was also the courthouse, was an imposing sight: the Bounty’s anchor, mounted on a plinth. Outside the hall, among several notices pinned up on a board, was one that warned the islanders about ‘personal incidents that could be sensationalised in the media’. It was signed by Steve Christian. Another reminded the locals that ‘malicious gossip’ was an offence.

As we wandered back to the Lodge, I was struck by the stillness in the lanes and a heaviness in the air. Dusk was falling, but it was still humid, and everything around us seemed exaggerated: the spring flowers were too vivid, as if daubed from a child’s palette, the bees buzzing around them were a little too loud. Perhaps I was affected by thoughts of why we had come here. But I smelt a definite whiff of menace.

My other lasting impression was the sheer ordinariness of the place. While the island had a kind of wild beauty, Adamstown looked like a run-down rural village in England or New Zealand. And it was tiny. Already I felt hemmed in, and unsettled by the omnipresent ocean, an immense blue blanket swaddling and smothering us, a wall separating Pitcairn from the world. The sense of isolation was overpowering.

Back home, we were greeted by the aroma of something burning. Baking was one of the new skills we would have to learn, for bread, like so many everyday commodities, could not be bought. A colleague had gamely put a loaf in the oven, but then forgotten about it, distracted by deadlines.

At 10 p.m. the living room went dark, prompting a chorus of groans and curses. Public electricity, supplied by a diesel generator, was rationed to ten hours a day. Most homes had a back-up system, with a bank of 12-volt batteries providing a few hours of extra power. However, in our ignorance we had already drained our batteries, and had to carry on working by candlelight.

Hours later, after everyone else had gone to bed, I paced up and down outside the house, trying to send my first day’s copy via satellite phone. The temperature had dropped, and I was surrounded by a darkness more complete than I had ever experienced. With no moon or stars, and no artificial light for hundreds of miles, I would not have found our back door again without a torch.

As I waved my phone around like a conductor’s baton, searching for a signal, I reflected on the weeks that lay ahead of me. Pitcairn would be no run-of-the-mill assignment, that was clear. And it was clear, too, that the story was about more than just the child abuse trials. It was about a strange little community, marching to its own tune in the middle of nowhere—and at the core of which we were now ensconced, rather uneasily.

CHAPTER 2 Mutiny, murder and myth-making

The next morning I got up and took a hot shower. Only later did I realise that, on Pitcairn, hot water does not simply arrive through the tap. A wood fire in a little shed near the house heats a copper boiler, which in turn heats cold water pipes leading to a storage tank. But in order for this to happen, a fire has to be built. And firewood has to be chopped.

Fortunately for the rest of us, Ewart Barnsley, the TVNZ journalist, was an early riser with a practical disposition. Shortly after dawn, he had chopped wood and lit the fire. From then on, he made that his daily chore.

We were discovering some of the other quirks of Pitcairn life. The ‘duncan’, for instance, which is an outside pit toilet. Ours was situated about 30 feet from the Lodge. The island does not have a sewerage system, and its only source of water, for drinking and washing, is rain.

Then there were the land crabs that lurked around, some the size of a dinner plate, turning a night-time trip to the duncan into a hair-raising ordeal. These fearsome-looking creatures usually tucked their soft bodies inside a coconut shell for protection, but we heard tales of crabs seen wearing a sweetcorn tin, a plastic doll’s head, and a Pond’s Cold Cream jar.

Should any of us encounter a particularly aggressive crab, or one of Pitcairn’s formidable spiders, help was close by, and it had an English accent. Three British diplomats—among 29 outsiders who had recently descended on the island, nearly doubling its population—were installed next door to us in the Government Hostel, another pre-fabricated dwelling for visitors. For the trials, just one new house had been put up, called McCoy’s after one of the mutineers, and it had been assigned to the prosecution team of three lawyers and two police officers. They found themselves living next door to Steve Christian, the Pitcairn mayor, who was facing court on six counts of rape and four of indecent assault. And the defence lawyers? They were sleeping in cells in the new jail.

At the Lodge, our other next-door neighbour was Len Brown, the oldest of the seven defendants. Len, who was charged with two rapes, was 78 and quite deaf, but still cut a physically imposing figure. Soon after we arrived, we saw him sitting in his garden, working on a carved replica of the Bounty—one of the wooden souvenirs that the islanders sell to tourists. For reasons unclear, a rusting cannon from the real ship stood on Len’s front lawn.

The mutiny on the Bounty is one of the most notorious events in British maritime history. Yet it was only one of a series of rebellions against the British Navy in the late 18th century. One uprising in 1797 involved dozens of ships and a blockade of London. Another led to the murder at sea of a captain and eight of his officers.

That few people are familiar with these incidents, while nearly everyone knows about the drama on board the Bounty, can be explained in one word: Hollywood. The mutiny inspired five films between 1916 and 1984, three of them made by American studios, with Fletcher Christian played by matinée idols such as Clark Gable, Marlon Brando and Mel Gibson. Studio bosses loved the story, with its exotic South Seas setting, scenes of swashbuckling adventure and cast of semi-naked Polynesian maidens, and so did generations of cinemagoers, who warmed to Christian and sided with him against the apparently cruel and sadistic Captain William Bligh. The mutineers’ descendants mostly shared that view of Bligh as the villain and Christian as the dashing young hero; to this day, they will not hear a word against their infamous ancestor.

The historical background is more complex than Hollywood has allowed. And it all began with breadfruit, a large, globe-shaped fruit.

Breadfruit trees had been discovered in Tahiti in 1769 by Sir Joseph Banks, the English naturalist, who urged King George III to introduce them to the West Indies as a cheap food source for slaves on the sugar plantations. The King appointed Bligh, a Royal Navy lieutenant, to lead an expedition, and in December 1787 a 220-ton former merchant ship, His Majesty’s Armed Vessel Bounty, set sail from Portsmouth with 46 officers and men. Among them was Fletcher Christian, the master’s mate and, effectively, Bligh’s chief officer.

Bligh was an ambitious 33-year-old, and an outstanding navigator who had accompanied Captain James Cook on his final voyage. Christian was 23, equally ambitious, and from a genteel—albeit no longer wealthy—family with strong links to the Isle of Man. He had sailed twice previously under Bligh, who regarded him as a friend and protégé.

The plan was to head to Tahiti via South America, collect some breadfruit saplings and transport them to the Caribbean. However, the Bounty ran into atrocious weather at Cape Horn, after which Bligh elected to go east, taking the longer route. The ship reached Tahiti’s Matavai Bay in October 1788.

Early European visitors had called the island an earthly paradise, and after nearly a year at sea the Englishmen could only agree. Tahiti’s white beaches were caressed by warm breezes; its trees hung heavy with fruit and its lagoons teemed with fish. The native men treated the sailors as ‘blood brothers’, while the beautiful, uninhibited women showered them with attention. Six months later, when it was time to depart, no one except the puritanical Bligh was keen to resume the rigours of shipboard life.

Bligh was convinced that it was Tahiti’s charms, so reluctantly relinquished, that triggered the events of 28 April 1789. Most historians now agree that, far from being a brutal despot, Bligh was an enlightened captain who kept his crew healthy and flogged only sparingly. But he was also prone to fly into rages. After the Bounty left Tahiti, he humiliated the thin-skinned, volatile Christian, branding him a coward and accusing him of stealing coconuts from a stash on deck. Their relationship had broken down—although probably not as a result of a gay liaison gone sour, as some have speculated.

Three weeks out of Matavai Bay, as the Bounty approached the Friendly Islands (now called Tonga), five men burst into Bligh’s cabin at dawn. With Christian pointing a bayonet at his chest, Bligh was made to climb into the ship’s launch, along with 18 loyal officers and men. He appealed to Christian, reminding him, ‘You have danced my children upon your knee.’ The latter, reportedly in a delirious state, replied, ‘That, Captain Bligh, that is the thing … I am in hell … I am in hell.’

Bligh and his followers were set adrift with no charts and only meagre supplies. In a remarkable feat of navigation, Bligh guided the launch across 3618 miles of open sea, landing on the island of Timor 48 days later. Amazingly, only one life had been lost: that of a quartermaster, killed not at sea but in a skirmish with Tongans. In Batavia (now Jakarta), Bligh found a berth on a Dutch East Indiaman, and in March 1790 he arrived back in England, where he recounted his tale to an astonished nation.

The mutineers, meanwhile, were searching for a refuge. They could not go home to England, and an attempt to settle on Tubuai, 400 miles south of Tahiti, was abandoned after clashes with the locals. The men split into two factions. Sixteen of them decided to chance their luck on Tahiti; the other nine, led by Christian, would continue their quest. The Bounty dropped the first group at Tahiti, but picked up some new passengers: 12 Polynesian women, six Polynesian men and a baby accompanied Christian’s band on their journey.

Two months later, while flicking through a book in Bligh’s library, Christian noticed a reference to ‘Pitcairn’s Island’. The island sounded promising, but it had been incorrectly charted, and another two months passed before he finally sighted it in January 1790. Christian led a party ashore, and when he returned he was smiling for the first time in weeks. Pitcairn was not only off the map, but it was also unpopulated, and it was a natural fortress—thickly forested, with towering cliffs and no safe anchorage. Yet it had fertile soil, fruit trees and (unlike now) a water source. The mutineers ran the Bounty aground and prepared to establish a new community far from civilisation.

The sailors divided the cultivable land into nine plots, one for each of them. The proud Polynesian men, who had been their friends and equals on Tahiti, received nothing; instead they were to be their servants. The Englishmen also took one ‘wife’ apiece, with the other three women shared among the six Tahitians. These actions created a deadly stew of sexual jealousy and racial resentment, which boiled over two years later.

After the wives of John Williams and John Adams died, the pair commandeered two of the Polynesians’ women. Enraged, the native men hatched a plot to murder the mutineers. But the latter were tipped off, and it was two Tahitians who were killed, one of them by his former wife.

In 1793 violence flared again. The four remaining Polynesian men stole some muskets, and within the space of one day murdered five Englishmen, including Fletcher Christian. Only John Adams, William McCoy, Matthew Quintal and Edward Young survived. Tit-for-tat killings followed, by the end of which all the Tahitian men were dead.

Calm then descended on the community—until 1798, when McCoy built a still and began producing a powerful spirit from the roots of the ti-plant. The men, and some of the women, spent their days in a drunken stupor, and it was in such a state that McCoy threw himself off a cliff. Quintal grew increasingly wild, and tried to snatch Young’s and Adams’ wives; the pair decided that they had no option but to kill him. They hacked Quintal to death with a hatchet. At last the cycle of bloodshed was over.

In 1800 Young died from an asthma attack. It was ten years since the mutineers had first spied Pitcairn. Of the 15 men who had settled there, only Adams was left.

Carved into a cliff high above Adamstown is Christian’s Cave, reached by a vertiginously sheer trail trampled by the wild goats that roam the island’s ridges and escarpments. It was to this windblown spot, a dark slash in the volcanic rock face, that Christian would retreat, so it is said, to scan the Pacific Ocean for British naval ships—and to reflect, perhaps, on the reckless act that had exiled him for eternity.

Once the Bounty was stripped and burnt to the waterline, the mutiny stopped being Christian’s story. He was no longer a leader, and little is known about his life on Pitcairn, apart from the fact that his Tahitian wife—called Maimiti, or sometimes Mauatua—bore him two sons and a daughter. There is still debate about whether he really died there, or somehow managed to return to England—stoked by a ‘sighting’ of him in Plymouth, and the failure ever to locate his burial site.

The only mutineer with a preserved grave is John Adams, and it is he, not Christian, who was the father of the Pitcairn community, who set it on the course it was to follow for the next 200 years.

Adams, an ambiguous figure, signed up for the Bounty as Alexander Smith, reverting to his real name on the island. Rough and ready, like the average working-class salt, he played a prominent role in the seizing of the Bounty and subsequent racial warfare. Then, after the killings, he underwent a miraculous conversion—at least, that was his account, and there was no one left alive to challenge it.

Adams claimed that Edward Young taught him to read, using a Bible retrieved from the Bounty, and that he was so affected by the Bible’s teachings that he repented of his misdeeds and embraced Christianity. After Young’s death he was left alone with nine women and the 24 children born to the mutineers during those violent early years; strangely, no children were fathered by the Polynesian men. And, according to Adams, all of them led lives of spotless integrity under his patriarchal guidance.

The outside world, meanwhile, was gripped by the mystery of the mutineers’ whereabouts. The men on Tahiti had been quickly tracked down and shipped home, then court-martialled, after which three of them were hanged. Fletcher Christian and his followers, though, seemed to have vanished.

The little society headed by Adams lived in complete isolation until 1808, when an American whaler, the Topaz, stumbled across it; the Topaz’s captain, Mayhew Folger, was astounded to be greeted by three dark-skinned young men in a canoe, all of whom spoke perfect English. Adams related his tale of sin and redemption to Folger who, after just a few hours on shore, left convinced that Pitcairn was ‘the world’s most pious and perfect community’. He informed the Admiralty about his incredible discovery, but the news was received with indifference; Britain was at war with France, and the mutiny was no longer of much interest in naval circles.

To each visitor after Folger, Adams gave a slightly different version of events, and few visitors interviewed the women, who were the only other witnesses. It was the start of the myth-making that was to obscure the reality of Pitcairn for the next two centuries.

By 1814 Adams was out of danger, following another chance visit, this time by two British naval captains. Enchanted by the new colony, they advised the Admiralty that it would be ‘an act of great cruelty and inhumanity’ to repatriate Adams and put him on trial.

Pitcairn’s period of seclusion was over. A stream of ships called, mainly British men-of-war, but also whalers and merchant vessels. All of them found a peaceful, devout society whose young people were healthy, modest and well educated. The legend of an island populated by reformed sinners, the offspring of murderers and mutineers, spread across the English-speaking world.

To outsiders, the idea of a Western-style community flourishing in such a faraway spot was compelling. Missionary groups dispatched crateloads of Bibles; other well-wishers, including Queen Victoria, sent gifts such as flour, guns, fishing hooks, crockery and an organ. Pitcairn was many things to many people. It was a religious fable. It was a fairy tale. It was the fulfilment of a Utopian dream.

The island’s fame grew in the late 19th century, after the locals rescued foreign sailors from a series of shipwrecks. Then in 1914 the opening of the Panama Canal put Pitcairn on the main shipping route to Australia and New Zealand. Liners packed with European emigrants would pause halfway across the Pacific so that their passengers could glimpse the island, and even meet its inhabitants, for—then as now—the islanders would board the ships to sell their souvenirs.

Jet travel destroyed the glamour of the ocean voyage, but while the rest of the world shrank, Pitcairn remained tantalisingly inaccessible, thus retaining much of its original allure. Children still scoured atlases for it; adults projected their escapist fantasies onto it; armchair travellers daydreamed about stepping ashore. The islanders, meanwhile, cultivated their own mystique, nurturing the romantic aura that drew tourists—and their American dollars—to their door.

The day after we arrived on Pitcairn, Olive Christian, Steve’s wife, invited members of the media to Big Fence, her sprawling home overlooking the Pacific. Like the rest of my colleagues, I had absolutely no idea what to expect.

When we got there in the early afternoon, 15 women—almost the entire adult female population—were assembled on sofas and plastic chairs arranged around the edge of the living room. The room, which had a lino floor, was as big as a barn; the walls were decorated with family photographs and a large mural of fish and dolphins. Through the front window we could see tall Norfolk pines clinging to slopes that tumbled steeply to the ocean.

The women represented all four of Pitcairn’s main clans: the Christians and Youngs, still carrying mutineers’ surnames, and the Browns and Warrens, descendants of 19th-century sailor settlers. The other English lines—Adams, Quintal and McCoy—had died out, although not in New Zealand or on Norfolk Island, 1200 miles east of Australia, where most people with Pitcairn roots now live.