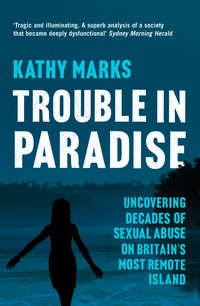

Trouble in Paradise: Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island

At the time of the Big Fence gathering, the names of the seven Pitcairn-based defendants were still suppressed by a court order. However, we were privy to this poorly kept secret. Every woman in the room was related to one or more of the men—as a wife, mother, sister, cousin, aunt or stepmother-in-law.

Looking around, I saw that, with a few exceptions, the women were solidly built. While some were dark-haired, with striking Polynesian features, others, with their fair skin and European looks, would not have stood out in an English village. All of them were casually dressed, many in shorts and singlets: practical choices, given the heat and ubiquitous Pitcairn dust.

We had been summoned to Big Fence, it turned out, to be told that their menfolk were not ‘perverts’ or ‘hardened criminals’: they were decent, hard-working family types. No islander would tolerate children being interfered with, and no one on Pitcairn had ever been raped. The ‘victims’ were girls who had known exactly what they were doing. It was they who had thrown themselves at the men.

As I digested this notion, which was being put forward with some passion, I noticed that a handful of people were dominating proceedings. These particular women were speaking over the top of each other, impatient to get their point across. Others said little, and looked ill at ease. Steve Christian’s mother, Dobrey, sat quietly, weaving a basket from pandanus leaves.

The talkative ones explained that under-age sex was the norm on Pitcairn. Darralyn Griffiths, the daughter of Jay Warren, one of the defendants, told us in a matter-of-fact way that she had lost her virginity at 13, ‘and I felt shit hot about it too, I felt like a big lady’. She was partly boasting, partly censorious of her younger self, it seemed to me. Others clamoured to make similar admissions. ‘I had it at 12, and I was shit hot too,’ said Jay’s sister, Meralda, a woman in her 40s. Darralyn’s mother, Carol, 54 years old, agreed that 13 was ‘the normal age’, adding, ‘I used to be a wild thing when I was young and single.’ Olive Christian described her youth, with evident nostalgia, as a time when ‘we all thought sex was like food on the table’.

The British police had misunderstood Pitcairn, they claimed: it was a South Pacific island where, to young people, sex was as natural as the ocean breeze. Olive said, ‘It’s been this way for generations, and we’ve seen nothing wrong in it. Everyone has sex young. That’s our lifestyle.’ Darralyn echoed her. ‘It was just the way it was. No one thought it was bad.’

We must have looked surprised. They were surprised we were surprised. Well, at what age did we start having sex, they demanded. It was clear, in this company and at this particular juncture, that the question could not be avoided. Some of our responses met with howls of derision. The women of Pitcairn did not believe that anyone could have lost their virginity at 18; the idea of being that old was simply preposterous.

The serious point of this was to persuade us that the criminal case was based on a misconception—and, furthermore, that it was all part of an elaborate plot. Britain was determined to ‘close the island down’, they said, because it had become a financial burden—a ‘thorn in the arse’, as Tania Christian, Steve and Olive’s daughter, put it. What better way to achieve that than to jail the men who were the very backbone of the community?

Why, though, we wondered aloud, would the women who had spoken to police have fabricated their accounts—accounts that, despite them growing up on the island in different eras and now living thousands of miles apart, were remarkably alike? At this point the Pitcairners produced their trump card: Carol Warren’s daughters, Darralyn and Charlene.

Charlene, 25 years old, with long, curly hair and a diffident manner, spoke up first, egged on by her mother. Charlene revealed that she had been one of the women who made a statement in 2000, alleging sexual abuse by Pitcairn men. But, she added, as others sitting around her clucked approvingly, she had only done so because she had been blinded by greed. She explained, ‘The detectives … dragged me to the police station. I didn’t know what I had done. I was ignorant. I was offered good money for each person I could name. They said I would get something like NZ$4000 (£1,500) for every guy. After I had added it up in my head, I was, like, “Whoa!” I just blurted everything out to them.’

Then it was her sister’s turn. Darralyn was 27; well built, with a fair complexion, she resembled Charlene physically, but was more self-assured. Darralyn told us that she had also made a statement—but, she said, only after being browbeaten by police. She claimed that detectives had asked her to ‘make up a false allegation against a guy here, because they didn’t have enough evidence to put him under’.

A New Zealand detective and child abuse specialist, Karen Vaughan, who had joined the British inquiry team, told Darralyn’s partner, Turi Griffiths, that if they had a baby daughter and brought her to the island, she would get raped too, Darralyn alleged. ‘I was shit scared. They told me if I tell the truth, everything will be fine. They said they’d heard from other people about my past. They asked me disgusting personal questions.’

Both sisters were living in New Zealand at the time of the investigation, and both told police that they were prepared to go to court. But ‘after I really thought about it, it was half and half … I wanted it just as bad as them. It was very much a mutual thing,’ said Charlene, referring to the men whom she had named as abusers. That re-evaluation took place after Charlene returned to Pitcairn. Darralyn changed her mind shortly before she, too, went home.

By now my head was spinning. We had had middle-aged matrons bragging about their sexual exploits. We had had Charlene and Darralyn outing themselves as victims, but not really victims. Now their mother, Carol, was declaring that no Pitcairn girl had ever been abused—and, almost in the same breath, telling us that she had had an unpleasant experience as a child. ‘It didn’t affect me,’ she said. ‘I was probably luckier than some I’ve read about. It was tried but nothing happened. I was ten at the time. But even at ten I knew it was wrong, it’s a bad thing. I screamed like hell.’

When she heard that Darralyn had spoken to police, Carol said, ‘I thought, what on earth is that girl thinking about? The silly idiot … Well, if that’s what she’s gone and done, I’ll have to stand by her.’ She went on, ‘I told the cops, not one of these girls went into this with their eyes shut. They knew exactly what they were doing. They weren’t forced by anyone. The women here are loose, and it’s not the men’s fault. What are they supposed to do?’

Carol then hinted at ‘some really bad stuff that I know about that’s happened on the island that’s a heck of a lot worse [than under-age sex] … That’s sick sex I’m talking about, between adults’. She was referring to adultery, it transpired, and as she uttered the word, Carol growled like an alley cat. ‘Maybe I’m old-fashioned, but to me that’s taboo,’ she said. ‘Some people don’t care. They don’t have morals.’

Like the others, Carol had a way of looking at you without meeting your eye. It was disconcerting. The women, with their permanently distant expressions, all seemed to be wearing masks. The outspoken ones laughed a lot, particularly at coarse jokes. They came across as both manipulative and naïve. They were not the type to be easily intimidated. They were feisty and opinionated: people who would be able to look after themselves.

But when conversation moved to the prospect of their male relatives being jailed, the women suddenly appeared vulnerable. ‘I wouldn’t want to be without the men,’ Meralda said softly. Carol interjected, ‘We’re lost as hell without them.’ Olive reckoned that, without the men, ‘you might as well pick Pitcairn up and throw it away, because no one is going to survive … We can’t look after ourselves.’ With the population already at crisis point, they claimed, if even a couple of men were locked up, there would be too few to crew the longboats and maintain the roads. Meralda questioned why Britain had singled out the able-bodied men. Olive said, ‘There’s no one who can replace them. They can’t bring outsiders in to run the boats. They’ve no idea what to do.’

Of all those present, Olive stood to lose most. Among the seven defendants on the island, she counted her husband (Steve), her son (Randy), father (Len) and younger brother (Dave). The six men facing court in New Zealand included her other brother, Kay, and her two other sons, Trent and Shawn. Like certain women in the room, Olive also had connections with some of the alleged victims. She lamented, ‘We live as one big family on this island, and nothing will ever be the same … Right now, with all this going on, maybe they should have hanged Fletcher Christian.’

We had been at Big Fence for several hours, and no one was showing any sign of moving. The women, it seemed, were willing to stay for as long as it took to win us over. When we got our cameras out, they smiled, repeatedly. We could take as many pictures as we wanted.

We had not, though, been offered so much as a glass of water. It was a hot afternoon, and my tongue was sticking to the roof of my mouth. After a few more photographs, the six of us left. We would never set foot inside Steve Christian’s house again. And some of those women would never again speak to us, or even acknowledge our existence.

The next day, two of those who had remained in the background invited us to talk to them privately. They did not wish their names to be used, and we met them on neutral ground; even so, the other islanders knew within hours that the interview had taken place.

The two were anxious to dispel the impression that Pitcairn was a hotbed of under-age sex. That had not been their experience when they were growing up, they claimed. I asked why they had kept quiet at Big Fence. ‘There’s no point in one little voice speaking up,’ one woman replied. She told us that the Pitcairners usually avoided confrontation. ‘If you’re opposed to something, you tend to defer. We all have to get along together. We’re a community. None of us can survive here on our own.’

The pair were already unpopular because they had not condemned the prosecution outright. One observed, ‘If you try to give a balanced view, you’re regarded as disloyal.’ The other had been called a ‘Pommy supporter’ and ‘puppet of the Governor’ while going about her business in the Adamstown square.

The women believed that the sexual abuse had to be stopped. ‘If it’s as bad as it’s been made out to be, then it needed to be addressed,’ said one. She added, ‘But I’m not condemning the guys. I don’t personally want to see them jailed. I feel very sorry for the guys. Yet we’re hurting for the girls. It’s a double-edged sword. We’re all related. We’re related to the victims. We’re related to the offenders. And whatever decision is made, it’s going to hurt everybody. The ripples are so widespread.’

One woman alluded to victims within her own family, and said that she admired the courage of those giving evidence. However, she went on, ‘I don’t know who’s done what to whom, and I don’t really want to know, because then I’ll have to live with that for the rest of my life. You go to bed at night, you can’t sleep for thinking about it. No one wants to take that on board.’

This off-the-record conversation, I remember, left me feeling like Alice in Wonderland. The women at Big Fence had promised us the real story. The two dissidents had given us another perspective. But theirs, too, was clouded by ambiguity.

Walking home, as we passed little groups of people chatting in the road, I was struck by a sense of life unfolding in parallel universes. On the surface, the island seemed innocuous, even banal. Then every so often you glimpsed something hard-edged and sinister. Which was the real Pitcairn?

CHAPTER 3 Opening a right can of worms

While exploring my surroundings in those early days before the trials began, I poked my head into the public hall, which doubled as Pitcairn’s courthouse. A familiar figure gazed back at me: Queen Elizabeth II, in a hat and pearls, clasping a bunch of flowers. There were, in all, three photographs of the Queen at the front of the hall, as well as one of the Duke of Edinburgh and one of the royal couple. On the same wall hung a Union Jack, together with a Pitcairn flag and a British coat of arms.

It was an overt display of patriotism of a kind rarely seen nowadays, and it was in striking contrast to the anti-British sentiments expressed at Big Fence, where most of the women seemed to agree with Tania Christian, Steve’s daughter, when she declared that ‘Britain can go to hell as far as I care.’

The reality was that, until Operation Unique started, barely a subversive murmur was heard around Adamstown. Pitcairn was Britain’s last remaining territory in the South Pacific, and its inhabitants were—as visitors often remarked—among Her Majesty’s most loyal subjects. Until not so long ago, ‘God Save the Queen’ was sung at public meetings, school concerts, even the twice-weekly film shows, while the British flag was flown on the slightest pretext. A number of islanders were MBEs, and several, including Steve Christian, Jay Warren and Brian Young, one of the ‘off-island’ accused, had been invited to Buckingham Palace.

Pitcairn’s origins were emphatically anti-British, of course; in Fletcher Christian’s day, there were few acts more heinous than mutiny. So it was an ironic twist when, a couple of decades later, the British Navy became the islanders’ guardian and lifeline. The captains of British warships that patrolled the South Seas in the 19th century, keeping an eye on that corner of Empire, felt responsible for the minuscule territory. They developed a sentimental attachment to the place and stopped there regularly, delivering gifts and supplies. They also found themselves settling disputes and dispensing justice in the fledgling community.

Russell Elliott, the commander of HMS Fly, who visited in 1838 after a difficult decade for the islanders, is recalled with particular fondness. Following John Adams’ death in 1829, the Pitcairners had emigrated to Tahiti, where many of them died of unfamiliar diseases. The rest, after limping home, spent five years under the despotic rule of an English adventurer, Joshua Hill, who convinced them that he had been sent out from Britain to govern them. When Hill left, they were then terrorised by American whalers, who threatened to rape the women and taunted the locals for having ‘no laws, no authority, no country’. Demoralised, the islanders begged Elliott to place them under the protection of the British flag, and he agreed, drawing up a legal code and constitution that gave women the vote for possibly the first time anywhere.

Pitcairn was now British, although for the next 60 years its only connection with the mother country was to be the visiting navy ships. In 1856, concerned about overpopulation, the islanders decamped again, this time to the former British penal colony of Norfolk Island; however, a few families returned, and the population—the origin of the modern community—climbed back to pre-Norfolk levels. Then in 1898 Pitcairn was taken under the wing of the Western Pacific High Commission, based in Fiji, which oversaw British colonies in the region. The WPHC did not trouble itself greatly with its newest acquisition: during a half-century of administrative control, only one High Commissioner visited—Sir Cecil Rodwell, who turned up unannounced in 1929.

In the meantime, the warships stopped calling, although the vacuum was partly filled, following the opening of the Panama Canal, by passenger liners. The captains and pursers of the merchant fleet took over the Royal Navy’s paternal role, ordering provisions for the islanders, carrying goods and passengers for free, and donating items from their own stores.

With the liners came emigration, and intermarriage with New Zealanders. While strong ties were forged between Pitcairn and New Zealand, the relationship with Britain remained fundamental, and one of the colony’s proudest hours came in 1971, when the Duke of Edinburgh and Lord Mountbatten arrived on the Royal Yacht Britannia and were transported to shore in a longboat flying the Union Jack from its midships. Official visits, to the disappointment of the locals, continued to be fleeting and infrequent, though.

There were, obviously, practical obstacles hindering more effective colonial scrutiny. Pitcairn, 3350 miles from Fiji, was hard to get to and even harder to get away from. In order to visit for 11 days in 1944, Harry Maude, a Fiji-based British official, had to be away from home for nearly six months. Communications were also primitive. Until 1985 the only way to contact the island was to send a radio telegram by Morse code.

But logistics were not the only issue. Pitcairn was tiny and remote, with no resources worth exploiting, and—unlike, say, the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic—it was of no strategic importance. When responsibility for the island was transferred from Fiji to New Zealand in 1970, the British Foreign Office reassured the High Commissioner to Wellington, who would now be supervising the colony, that ‘the duties of the Governor of Pitcairn are not onerous’.

If recent governors heard that statement, they would sigh. In the past, their role as the Queen’s representative on Pitcairn was mainly ceremonial, although they did have the power to pass laws and override the local council. But since allegations of widespread sexual offending came to light, the island has taken up an inordinate amount of their time.

While the scandal broke in 2000, the first hint of it actually came in 1996, with an incident that not only foreshadowed what was to follow, but set off a chain of events that led inexorably to Operation Unique, and the women of Pitcairn breaking their silence. An 11-year-old Australian girl living on the island with her family—let us call her Caroline*—accused Shawn Christian, Steve’s youngest son, of rape. Her father reported it to the Foreign Office, and Kent Police, based in southeast England, offered to investigate.

Dennis McGookin, a freshly promoted detective superintendent and genial ex-rugby player, was given the case. Accompanied by Peter George, an astute detective sergeant, he flew to Auckland in September 1996, where the pair met Leon Salt, the Pitcairn Commissioner, and the British official in charge of servicing the practical needs of the remote territory. (Among other things, the Commissioner organises the delivery of supplies.) The three men travelled to Pitcairn on a container ship, the America Star; arriving in a big swell, they descended the ship’s wildly swinging Jacob’s ladder into the waiting longboat.

Despite Pitcairn having been a British possession for 160 years, McGookin and George were the first British police to set foot there. They were nervous about their reception; yet the islanders, including 20-year-old Shawn, could not have been friendlier. Shawn readily admitted to having sex with Caroline, saying that it had been consensual. He showed them love letters from her, and even escorted them to the sites of their encounters, which included the church.

Caroline’s family had already left the island. She had been questioned by police in New Zealand, and was said to be very tall for her age, physically mature and ‘quite streetwise’. She had made the rape allegation after her parents caught her coming home late. Despite her age, the detectives decided just to caution Shawn for under-age sex.

The inquiry was over in a day, but the Englishmen had to wait to be picked up by a chartered yacht from Tahiti. They resolved to spend their time addressing the issue of law enforcement.

Pitcairn had never had independent policing. The island, theoretically, policed itself. The Wellington-based British Governor appointed a police officer, and the locals elected a magistrate, who was the political leader as well as handling court cases. Until Dennis McGookin and Peter George appeared, the only law was another islander.

The police officer in 1996 was Meralda Warren, a sparky, extrovert woman in her mid-30s. (Meralda was one of the vocal participants at the Big Fence meeting.) While she was bright, Meralda had no qualifications for the position, nor had she received any training. ‘Everyone on the island had a job, and that just happened to be hers,’ says McGookin. Meralda was also related to nearly everyone in the community. If a crime was committed, she might have to arrest her father, or her brother, or one of her many cousins.

History indicated, though, that she was unlikely to find herself in that delicate situation. Her predecessor, Ron Christian, who had been the police officer for five years, had never made a single arrest. Neither had the two previous incumbents, of seven and 21 years’ service respectively. No one had been arrested since the 1950s. The Pitcairners, it seemed, were extraordinarily law-abiding. All Meralda did was issue driving licences and stamp visitors’ passports. To be fair, that was all her predecessors had done.

The magistrate in 1996 was Meralda’s elder brother, Jay, later to go on trial himself. Jay, who was on the longboat when we arrived, had occupied the post for six years. Like Meralda, he had no qualifications or training, and was related to nearly everyone on the island. That could have been tricky, but fortunately for Jay, not a single court case had taken place during his time in office. And previous magistrates had been similarly blessed. The Adamstown court had not sat for nearly three decades.

Not that the locals would have feared the prospect of jail. The size of a garden shed and riddled with termites, the prison—a white wooden building—had never held a criminal. Lifejackets and building materials were stored in its three cells.

The British detectives were unimpressed with Meralda and Jay. According to Peter George, whom I interviewed in the Kent Police canteen in Maidstone in 2005, ‘It was glaringly obvious, bluntly speaking, that their standard of policing was not really adequate.’

When the police left Pitcairn at the end of their ten-day stay, the islanders, including Shawn Christian, waved them off at the jetty. Soon afterwards, the Governor, Robert Alston, wrote a letter to the Chief Constable of Kent Police, David Phillips. Thanks to McGookin and George, he said, the matter—which ‘had the potential to turn into a long, drawn-out and complicated legal case’—had been satisfactorily resolved. Alston added that the visit had ‘had a salutary effect on the islanders and one which will remain with them for a long time’. As a token of gratitude, he sent Phillips a Pitcairn coat of arms, to be displayed at Kent Police headquarters.

Dennis McGookin was not so convinced about the salutary effect. Back in London, he informed the Foreign Office that the island needed to be properly policed. Britain was not prepared to fund a full-time police officer for a community of a few dozen people. Instead, it decided to recruit a community constable to travel to Pitcairn periodically and train the local officer.

In 1997 Gail Cox, who had been with Kent Police for 17 years, was selected for the job. Cox was easygoing and gregarious; she had worked in the traffic section, in schools liaison and on general patrol duties. The Daily Telegraph newspaper, which interviewed her before she left, reported that she was ‘a practised hand at dealing with pub brawls and squabbles between neighbours’, and ‘highly regarded for her ability to defuse situations before they turn nasty’. Cox told the paper that ‘if the line needs to be drawn, it will be drawn, and I am not frightened to draw it’. Those words were to prove prophetic.

Leon Salt, the Auckland-based Commissioner, accompanied Gail Cox to the island and introduced her to the locals. ‘I put on this jokey persona, and they seemed to like that,’ she told me when I met her in Auckland in 2006. ‘They were very accepting of me. I became part of the community.’

Cox spent 12 weeks on Pitcairn, and established a good rapport with the islanders—perhaps too good. ‘A lot of people are romanced by the place, and I fell for it,’ she says. ‘I saw the community through rose-coloured glasses. I thought it was this really idyllic place, and everybody was really nice.’