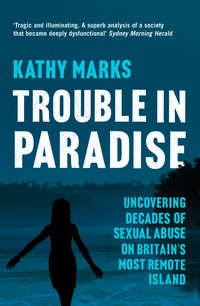

Trouble in Paradise: Uncovering the Dark Secrets of Britain’s Most Remote Island

In August 2000 Peter George and Robert Vinson, the detectives assigned to Operation Unique, returned to the Antipodes to start tracing the 20 women on their list: most of them lived in Australia or New Zealand, with a few in Britain and the United States. Accompanied by two New Zealand detectives, Karen Vaughan, the sharp-witted willowy blonde with child abuse expertise, and Paula Feast, police worked at a hectic pace—flying into a city, hiring a car and often just turning up on people’s doorsteps. Yet ‘every door we knocked on,’ George told me, ‘we got the same response … Every Pitcairn girl, and I mean every single one, a 100 per cent hit, had been a victim of sexual abuse to varying degrees.’ Vinson remembers, ‘We got disclosure after disclosure. It was staggering. It was like opening the floodgates for some of these women.’

The victims, by then in their late teens to late 40s, described incidents covering the whole gamut of abuse, from relatively minor assaults to violent rape. Some recalled blighted childhoods during which they were targeted by half a dozen or more Pitcairn men. The majority named more than one offender. In numerous instances, the abuse had started when they were three to five years old.

Most had kept their experiences to themselves, confiding in no one, not even their husbands. Now their husbands were hearing for the first time about the horrors of growing up as a girl on Pitcairn. Reliving it all was traumatic for the women, some of whom went into long-term counselling after telling their stories. Relationships and families were placed under enormous strain.

The first group of women told detectives about older victims, including friends and relatives, who had also been abused. Abandoning their 20-year time limit, police interviewed those women too, drawing a new line at 1960; before then, the relevant sexual offences law did not apply on the island.

By the end of the investigation, 31 victims—including two men—had spoken to police, naming 30 offenders, 27 of them native Pitcairners. Nearly every island male from the past three generations had been implicated; almost a third of those named were dead. Among the outsiders alleged to have taken part was a New Zealand teacher posted to Pitcairn in the 1960s, Albert Reeves.

Nearly a dozen women had made accusations against brothers, uncles or first cousins. But incest was not the only reason why Operation Unique at an early stage became, in Robert Vinson’s words, ‘very messy’. With every victim who was tracked down, the connections between those involved grew ever more excruciatingly tangled.

Belinda and Karen had been the first to disclose abuse. Next police spoke to Catherine, who claimed that Belinda’s father had raped her. Detectives then questioned a woman called Gillian, who—as well as recounting her own experiences—suggested that they contact two sisters, Geraldine and Rita. The pair told police that they had been raped as little girls. Their assailant, they said, was Gillian’s father.

Gillian’s uncle was allegedly an offender also, and so was her grandfather. Her first cousin was a victim. So was a relation of Geraldine’s and Rita’s. Their brother was said to be an abuser.

As the layers of secrecy that had enclosed Pitcairn for decades were peeled away, a picture emerged of almost systematic abuse. Many families allegedly contained both offenders and victims. How would those families cope with the fallout?

News travels fast along Pitcairn’s ‘coconut grapevine’. Just from the engine noise, the islanders can identify the driver of any quad bike that passes their house. They claim to know what everyone else is up to, at any hour of the day or night. ‘The jungle drum of Pitcairn is unbelievable,’ says Mary Maple, a former teacher on the island.

The grapevine extends across New Zealand, Australia and Norfolk Island, and during 2000 it buzzed with stories of English police questioning Pitcairn women. So when Peter George and Robert Vinson arrived at Pitcairn aboard a 48-foot yacht in September, no one was in any doubt as to why they had come.

After interviewing the island women, detectives were questioning the men. They had already spoken to suspects in New Zealand and Australia. Now it was the turn of those who lived on Pitcairn. Vinson and George set up video-recording equipment at the Lodge, where they were staying, and invited the men in one by one. While they were questioning Dave Brown, Len’s son and Olive’s brother, the power went off. Dave obligingly helped them to start up the generator, enabling them to resume his interview.

Despite the circumstances of their visit, the two Englishmen were received hospitably. ‘We were greeted with open arms, even by the accused,’ says Peter George, who recalls people ‘bringing us fish and freshly baked cakes … It was surreal.’

Beneath the surface, though, the community was in turmoil. When police began to ask questions, ‘everyone got the fright of their lives’, says Neville Tosen, the pastor. ‘Some of the men were quite clear that they were going to go to jail. They started cutting firewood for their mothers and wives, laying in stocks for a long period. They thought they were going to be taken off the island.’

Terry Young, who had promised his father, Sam, on his deathbed that he would look after his mother, Vula, was especially anxious. So was Dave. ‘I’m in trouble, no question,’ Dave told several people. ‘I’m going to jail … They’re going to lock me up and throw away the key.’ Even men who were not under scrutiny were alarmed. One older islander told an outsider, ‘They [the police] are going back 20 years. If they went back further, there’d be others.’

Elderly women who depended on their sons saw their whole future at risk, says Neville Tosen. ‘One mother was telling her son to come clean. Another was beside herself with worry. She said, “The police have come, and they’re going to take my boy away and hang him.”’

While Tosen had long had his suspicions, he was appalled to find out the scale of the alleged abuse. Above all, he was at a loss to comprehend how the older women, the mothers and grandmothers, could have allowed it to happen. It seemed obvious to him that they must have known. He and Rhonda spoke to the matriarchs. ‘We said to them, “Where were you when this was going on? You’re the elders of the island, surely you must be unhappy?” And they replied that nothing had changed. One of the grandmothers said, “We all went through it, it’s part of life on Pitcairn.” She said she couldn’t understand what all the fuss was about.’

The couple were feeling increasingly isolated. The communal satellite phone never seemed to be working when Tosen tried to reach Adventist regional headquarters. ‘We couldn’t get a message out of Pitcairn,’ he says. ‘We couldn’t even contact our kids. I also wrote letters to the Church administration, saying I was concerned about things on the island. They never arrived.’

Accompanying police on their visit was Eva Learner, an English social worker, who was sent out to support the locals and assess the impact of the investigation. In a report to the Foreign Office, Learner said that the men were ‘in [a] distinct state of shock and fear … very weepy … depressed and withdrawn’. Within the wider community, she encountered ‘general disbelief … about the nature and extent of the alleged abuse’: the islanders could not grasp ‘why the matters being investigated were of concern … or how they might be damaging to young women and children’. Mothers, Learner wrote, ‘professed difficulty in understanding that this had happened to their daughters’.

When the police departed, the locals thanked them. ‘They thought we were going to go away and never come back,’ says Peter George. Six months later, in March 2001, some of the team returned for more interviews; in October that year they visited yet again. By then, according to Karen Vaughan, who went on the two latter occasions, ‘it was clear they wished we’d go away … They thought we’d go there once and then realise how difficult, logistically, it was to pursue. The men just thought they could get away with it.’

By mid-2001 police had finished their inquiries and built up an extensive file of evidence. But Leon Salt was deeply sceptical, and predicted that they would get no further. Salt, who had opposed a prosecution from the outset, told detectives, ‘The women may speak to you, they may give you statements, but you’ll never get them to go to court and give evidence. You’ll never get the Pitcairners to testify against each other.’

Now that I was on the island, with the trials starting shortly, I was about to find out whether or not he was right.

CHAPTER 5 The fiefdom and its leader

It was Tuesday morning, which meant that Pitcairn’s one shop, situated on the main road, a couple of banana groves down from the square, was open for business. But you had to be quick, for it would be closed by 9 a.m.—and if you missed it, you had to wait until Thursday, when it opened for another solitary hour of trading.

The small shop was crowded, although probably no more than a dozen people were browsing the dusty shelves, stacked with tins of lambs’ tongues and condensed milk. Olive Christian, a grandson on her hip, was inspecting bottles of bleach, while her mother-in-law, Dobrey, chatted animatedly in Pitkern to another elderly islander. Olive’s son, Randy, and several other men who were about to go on trial stood around, laughing loudly at some private joke. They were mostly barefoot, and carried fishing knives in their belts. As Claire and I roamed the aisles, a figure in a baggy grey T-shirt leant over a freezer of meat. ‘We don’t like reporters here,’ said Dave Brown, with a half-smile.

Short and stocky, with a bushy moustache, Dave was charged with 16 offences, including indecent assault and gross indecency with a child. But, like the other defendants, he was free on bail, and for now he was just gassing with his mates.

Behind the till, entering purchases in tattered account books labelled simply ‘Dobrey’ or ‘Olive’, was Darralyn Griffiths, née Warren. Darralyn had withdrawn from the case, claiming that she had been coerced into giving a statement; it was common knowledge, however, that she and Dave had had an ‘affair’ that began when he was 34 and she was 13. It had prompted many a sly wink at the time, although not from Dave’s wife, Lea, or Darralyn’s mother, Carol, whose main objection had been that Dave was married.

Also open that morning, again for the blink of an eye, was the minuscule post office, presided over by Dennis Christian. Dennis, the postmaster, was charged with three sexual assaults. Considerably more forthcoming than Dave, he explained to us politely that Pitcairn’s once booming stamp business was in decline. ‘Hardly anyone mails any more,’ he said. ‘Everyone jumps on the internet nowadays.’

The library, too, had unlocked its door for an hour, revealing a closet-sized space and shelves piled haphazardly with Bounty-related books, airport novels and travel guides. All could be borrowed indefinitely, without risk of a fine. Next door, the island secretary, Betty Christian, was sweeping out her office, which had another picture of the Queen on the wall. Outside, a few of the older women were swapping gossip on the wooden bench, which was known as the ‘bus shelter’.

I had now met, or at least laid eyes on, all seven of the Pitcairn-based defendants: Randy Christian and Jay Warren on the longboat; Steve Christian in the pink bulldozer; Dave Brown at the shop; Dennis Christian at the post office; and Len Brown, our next-door neighbour, in his garden. The seventh man was Terry Young, who lived near the store with his mother, Vula. I had passed him in the main road, a large, lumbering figure. Terry was charged with one rape and seven indecent assaults.

Within two or three days of landing, we knew who was who among the 40 or so Pitcairn residents. (Half a dozen were away.) And they, of course, knew who we were: six despised reporters tramping around their island. We could not have avoided the locals if we had tried. Every time we stepped out, we bumped into them; often as we walked along the dirt tracks, they would overtake us on the quad bikes that they hopped on even for short trips. I was never sure whether to wave: it seemed rude not to, but sometimes the only response was an icy stare.

Not everyone was unfriendly. Outside the medical centre, I met a chatty, baby-faced Englishman: Mike Lupton-Christian, who is married to Brenda Christian, Steve’s sister. Mike and Brenda had met in England, and had moved to the island in 1999 with her son from a previous marriage, Andrew. Mike, who had added Brenda’s surname to his, appeared to be well suited to Pitcairn life. A former manager of retail and leisure services for the British military, he had a practical nature and was not afraid to get his hands dirty. But his attempts to muck in had so far been frustrated.

Mike, who was qualified to drive heavy machinery, was keen to use Pitcairn’s big red tractor. He needed a local licence, but when he applied to the council’s internal committee, chaired by Randy Christian, nothing happened. He made inquiries. Still nothing happened. ‘They kept saying things like “After the next ship’s been”,’ said Mike.

Vaine Peu, an amiable Cook Islander and the partner of Charlene Warren, told a similar story; Turi Griffiths, Darralyn’s husband, also from the Cooks, could not get a licence either. As for Simon Young, an Englishman who had settled on Pitcairn with his American – Filipina wife, Shirley, he had managed to secure a licence—but only for an old blue tractor, and only for collecting rubbish, which was his job. Mike, Vaine, Turi and Simon had one thing in common: they were all outsiders. Meanwhile, two local teenagers were being trained to drive the big red tractor.

Those who could not drive the tractor, which was used in countless chores, most notably to plough the islanders’ gardens, were dependent on those who could. And those who could were men who had been born on Pitcairn and spent their lives there: the ‘Big Fence gang’, as they were called.

If the big red tractor was a symbol of power from which outsiders were excluded, it was eclipsed by the longboat—Pitcairn’s umbilical cord, and the sole preserve of Steve Christian and his followers.

Such is the aura surrounding the longboat that it was an anticlimax to discover that it is just a large open boat with an outboard engine and an aluminium hull. The boat’s mystique dates from the days when it was made of wood, powered by oars, and hauled up the slipway by hand. But while less muscle may be required now, its significance has not diminished: without it, Pitcairn could not function. The boat—or boats, for there are two of them—collect people and supplies from the ships in all weather. Cargo, including fuel drums and timber, is lowered in a net; for those standing underneath, it can be dangerous work. The heavily laden vessel is then guided back into shallow, surf-lashed Bounty Bay, and it is their skill in accomplishing that task in the wildest conditions that gives Pitcairn’s men their intrepid reputation.

The longboat slows down as it approaches the cove and pauses, with its motor idling. The engineer turns round to face the open sea; when he spots a suitable wave, he opens the engine up at full throttle. The boat is swept forward and surfs into the bay through a slender, rock-studded channel, skidding to a halt by the jetty—which, for passengers, is like landing at the bottom of a helter-skelter. There is little room for error, though, and islanders have been killed or seriously injured on occasions when the swell has seized the boat and dashed it against rocks.

For the local boys, joining the crew is a rite of passage, and they long to be skipper or coxswain, just like other boys dream of driving a train. The coxswain has the most kudos of anyone on the island. In an exceptionally macho society, he is the most macho figure of all.

Steve has been a coxswain since the age of 17. Randy—the only one of Steve’s sons living on the island, and thus seen as the heir apparent to his political power—is a coxswain. So is Dave Brown. So is Jay Warren. Those men were always at the back of the boat, in charge of the tiller or engine. Len Brown, who in his day headed one of Pitcairn’s leading families, was among the island’s most capable engineers and coxswains.

Vaine Peu, Simon Young and Mike Lupton-Christian had all asked to be trained for the key roles. But the locals were unenthusiastic, for according to them, you had to have grown up on Pitcairn. So ‘the boys’, as they were known, continued to control the longboat—and, with it, the community’s access to resources, its economy, its very survival.

As of 2004, Steve and Randy occupied the highest-ranking official positions on Pitcairn. As mayor, Steve was the community leader and chairman of the local council, which administers the island day to day. (The Governor wields overall authority.) Randy was chairman of the influential internal committee, which, among other things, allocated jobs. The pair also headed the unofficial hierarchy, for the real power base on the island was not the public hall, where the council met monthly, but Big Fence, Steve’s family home, where important decisions were made by his ‘inner circle’, and the same men gathered on Friday nights for rowdy drinking sessions.

Only native-born Pitcairners were part of the gang. Outsiders, particularly men, were regarded with hostility and suspicion. Steve and his mates, it is said, saw them as a threat to their jobs, and to the cosy way they ran the place for their own benefit. ‘They hate outsiders with a vengeance,’ a former Pitcairn teacher told me. ‘It’s their rock, and they don’t want anyone else on it.’

At the same time, Pitcairn is desperate for new blood. From a high of 227 in 1937, the population has dropped to around 50. Yet as much as newcomers are needed, they are feared and disliked, and also looked down on, because they lack the Bounty lineage. The locals ridicule them for breaking invisible protocols, and say of them in Pitkern that they ‘cah wipe’—do everything wrong.

According to Mike Lupton-Christian, as an outsider, ‘you’re actually treated quite badly … They don’t like people coming in with new ideas or doing anything better than them. You become very unpopular if you disagree with them.’ Mike’s house, built high on a hillside overlooking the Pacific, is derisively called ‘Pommy Ridge’ by other islanders.

In the past, some newcomers have turned up starry-eyed and then left, unable to deal with the hardships of Pitcairn life. But outsiders are expected to fail. Nola Warren, one of the matriarchs, says, ‘People from outside can’t live here. They’ll never settle down. They wouldn’t be able to cope.’

Some are not given much of a chance. Nicola Ludwig and Hendrik Roos, from the German city of Leipzig, were ideal immigrants: young, strong and fit, with small children. They loved the outdoors, and were eager to adopt a self-sufficient lifestyle. Nicola, whose family is now in New Zealand, told me recently, ‘We went to Pitcairn for an adventure and to get away from the outside world. We were absolutely naïve about the place. We thought it was this little community full of greenies, where everyone is nice to each other.’ Although Hendrik pitched in, particularly on the boats, the Pitcairn men ostracised him and subjected him to anti-German insults. Eighteen months after the family arrived, a container ship offered them a free passage to Auckland. They packed up and left.

Some islanders are treated as outsiders, too. Brenda Christian—small, but very strong and fit—is always in the thick of it with the men, flitting around the boats and shouldering heavy loads. Yet Brenda is not considered a true Pitcairner. She left the island at the age of 18 and did not return until 30 years later.

Like Brenda, Pawl Warren has an obvious rapport with island life. Shaven-headed Pawl, who gave us a fright when we first saw him on the longboat, left Pitcairn as a baby and grew up in New Zealand. In 1993, inspired by the Hollywood films about the mutiny, he moved back with his wife, Lorraine, and three children. Pawl describes the island as ‘a magical place’, but adds, ‘It’s not been easy to fit in here, because the hierarchy was already established.’

Even locals who have not lived away may experience similar problems. Tom and Betty Christian—elders of the Church, well travelled, well read and relatively affluent—are envied and distrusted by many of their fellow islanders. The couple, who have pioneered most of Pitcairn’s commercial ventures and undertaken overseas trips sponsored by the Adventist Church, find themselves increasingly isolated in their own community.

In the early 1990s, in an effort to boost the population, British administrators introduced a scheme to attract young Norfolk Islanders. A few people took up the offer of work and cheap housing; none of them ended up staying for long. Even Randy Christian’s wife, Nadine, who has married into the island’s most powerful family, confides, ‘The Pitcairners have their own way of doing things. I’ve had to try and do stuff the Pitcairn way, but it’s very difficult.’

I asked Matthew Forbes, Karen Wolstenholme’s successor as Deputy Governor, who, in his opinion, had been the last outsider to settle successfully on the island. After a long pause, Forbes suggested Samuel Warren, an American whaler who arrived in 1864.

Nadine, Steve Christian’s daughter-in-law, had been one of the talkative women at the Big Fence meeting; for the time being, she and other female relatives were as close as we would get to Steve. However, we soon came to know his voice well, thanks to the VHF radio system that is Pitcairn’s domestic telephone network. Every house and public building has a VHF unit. If you want to speak to someone, you holler out their name three times on the main frequency, Channel 16. (Only a first name is needed.) When they respond, the two of you switch to another channel—and everyone else adjusts their sets, in order to eavesdrop.

The radio in our living room crackled into life dozens of times a day, as the islanders got in touch with each other to chat or make plans. Steve’s rich tones rang out frequently. He might have been about to go on trial, but he was, unmistakably, still in charge. It was he who made public announcements, informing people when the next ship would be calling, or telling them not to worry if they saw smoke rising—‘We’re just burning rubbish.’

While Steve was elected mayor in 1999, unofficially he had been a leader since his teens. Good-looking, self-confident and powerfully built, he had always stood out: cleverer than his peers, a bit more articulate, and possessing a certain raw charm. His late father, Ivan, had been magistrate for eight years, and his mother, Dobrey, remains a formidable woman. Despite a strict upbringing, Steve was described as a tearaway by a Royal Air Force team stationed on Pitcairn in the 1970s, when he was in his early 20s. In a report to British authorities, the team also tipped him as a ‘future strongman’, and said that he would be a ‘severe loss’ if he decided to emigrate. Steve never did leave, except for limited periods, and that has been a source of strength.

In his youth, Steve had the pick of the local girls, and he eventually married Olive Brown, Len’s eldest daughter, although—much to people’s amusement—he reportedly also had affairs with her two younger sisters; he was referred to as ‘the man with three wives’. The birth of three sons, Trent, Randy and Shawn, consolidated his status. In addition, Steve has a multitude of talents. It is said of him that he can fix anything, and that he is a person who gets things done. A few years ago, when the islanders were heading home in a gale and rough seas, a rope got caught in the longboat’s propeller. Steve dived overboard, cut the rope and was back in the boat before some of its occupants had realised anything was amiss.

On another occasion, when a woman was seriously ill, her husband contacted a specialist in California via ham radio. (Until recently, the only health professional on Pitcairn was a nurse.) The doctor proffered a long-distance diagnosis, and Steve, on his instructions, fashioned two surgical instruments which the nurse then used to perform an emergency procedure. The woman believes that Steve saved her life. ‘It was a miracle, and he was part of that miracle,’ she says.