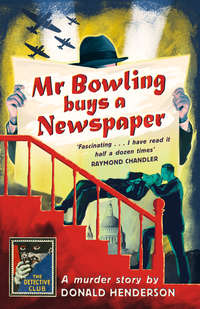

Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper

He kept on with the firm and went to see ‘the office’ just as usual, and was just as patient with Mr Watson, his most self-centred client. Mr Watson depressed him very much, a dreary fellow in a brown trilby hat, with a brownish outlook. He thought we should lose the war, because he didn’t think any Empire had the right to rule for more than a thousand years. He wasn’t a conchie, but on his own admission, only because he had not the moral strength to face a tribunal. All he thought about was whether his money was safe, and whether his various bits and pieces were safely covered by insurance policies. He never missed a premium, never had a drink, never had a woman. He said so. It was the way he put it. Women were a sort of meal. But he was never hungry. He’d been married, but you could only imagine what it must have been like. Perhaps just at Christmas, just to cheer the old woman up.

Mr Watson lived in Fulham too, Number Ten, Peel Road, one of a row of little red houses. At the back was a row of little gardens, mostly full of potatoes and cabbages now, the war effort. Quite a lot of houses had been hit in Fulham, so that London looked like a dirty old woman who had had a lot of her teeth out. She grinned, waiting for the dentist to come back again and pull out a few more. Perhaps the dentist would come again and perhaps he wouldn’t, for the present her agony was almost forgotten. The neighbours thought: ‘Yes, but she looks tidy again. More or less.’ Mr Watson had a married daughter called Mrs Heaton who came up from Kingston about twice a year. She wore rather cheap furs and ran a baby Austin. Mr Bowling was very interested because he knew she wouldn’t get a penny when Mr Watson died, although she fondly thought she was going to get everything. Mr Watson had one day confided his will. The money was going to a dogs home. Mr Watson had been so fond of a spaniel which had passed on, he would not purchase another dog. But he liked to visit various doggie establishments, and in the parks would stop all and sundry and enquire of the owners their endearing habits. So there was something human about him, like there was about everyone if you searched really hard. After his wife’s funeral in Fulham, and after he had got his affairs a little in order, War Damage Claim safely listed and sent in, and his furnished room in Notting Hill Gate chosen, a nice long way off, Mr Bowling sat on his divan and had a bit of a think about Mr Watson. He thought how awful he was about money, it was dreadful wanting money just for the sake of having it in the bank, better to collect fag cards, for all the good it did you or anybody else. You could forgive a decent motive. You could not forgive miserliness. It was, he confessed to himself, a little like trying to find a reason for murdering Mr Watson, but it had to be admitted he was a fair and sporting choice. If he was a happy, generous man, one would not dream of plotting against him, it wouldn’t be cricket. And then, another sound reason, he’d fled from town when the Huns started coming, and crept back when the Huns had gone again. The man simply asked for it. Asked for it. He must die for Art! That was what it would amount to. His death would get a bit of good music printed and published. He would leave something to posterity after all.

He sat and tried to think about money. He was not good at it. He was too artistic, too creative, if you wanted to know. The mere thought of insurance made him shudder, but a chap had had to do something. Salary and commission, that’s what it had boiled down to. ‘Oh, I tootle round,’ was what he explained to friends. ‘See what I can pick up. What about you, old man? Your life insured? Why not come to my people?’ There wasn’t much in it. But it scraped up a living. Hardly enough to get tight on, though, let alone keep a wife. As for kids! ‘No, siree! No bally fear!’

In his new room at Number Forty, he thought:

‘If old Watson wrote out a policy saying that if he kicked the bucket he’d leave a couple of thousand quid to me, then it would be worth bumping him off. That’s the ticket, I think?’

Yes, but how to make him do that? Forgery? No, that wouldn’t be cricket, a chap wasn’t a criminal.

He thought:

‘A pot of paste. If I pasted the policy he thought he was signing—over the real one, allowing only the bottom for the signature? Then he’d sign the one that mattered to me, and a steaming kettle would do the rest. By jove, yes! Think it would work? Or would he spot it?’

He kicked off his shoes and lay down flat. ‘I wonder,’ he thought.

Mr Bowling’s background was in reality so little a background at all, that to paint one at all needs a cycloramic effect. It was a colourful fusion of people in shabby places. Had they homes, it would have been a Dickensian background; but these homes were, in the main, furnished, single rooms, occasional flats. Sir Hugh Walpole wrote of duchesses and balls and stately houses, of the hills and lakes of Cumberland. Mr Bowling had had relations with a substantial background once, but his story removed him from it as a child, and placed him, for want of a better description, with the Moderns, though not the Moderns who belonged to Noel Coward. They didn’t drink cocktails, they drank mild and bitter, or draught cider when really hard pressed, and fell about Hammersmith’s houses filled with it and Red Biddy. No mansion-flats for them, and less and less evening dress. They didn’t go to theatres. They went to pubs and concerts, dodged or seduced landladies, and remained the people who mattered when England went to war. They knew the Labour Exchange and the Army Medical Board better than most. They had no influence, no wires to pull, and told each other: ‘I hear they’re taking on men, four quid a week, dear. Why not pop along and see? I know it’s not you—but it’s better than this?’ You went along and the chap was decent, but he saw you were a gentleman and he was slightly embarrassed. He was afraid the work was dirty and rough. ‘No clerical jobs, you see, they’re all taken.’ They thought at the Labour Exchange that an actor, author or musician temporarily a bit desperate for cash, could only fit into clerical work, and there was none. ‘Would you drive a Sainsbury’s van?’ they sometimes asked. ‘But it’s hardly you, it is. I don’t suppose they’d take you on.’ You couldn’t even draw the dole, because you hadn’t been a salaried worker for at least six months. You had to queue up with the scum of the earth (which you never did) and be ‘on the Parish’. Very tasty. But how different when the same government who thus humiliated you decided to go to war! ‘Bloody heroes now,’ Mr Bowling laughed good-naturedly at Queenie about it. ‘Nothing too good for us now, what?’ He was perfectly good-tempered about it. In just the same way, when he had sent in his War Damage Claim, he realised with something of a latent shock that he had lost every one of his musical compositions, the accumulated work of years. ‘Why, there was a bally thing there I wrote at school, when I used to play the organ in chapel,’ he laughed sadly. ‘I’ve lost the lot … But, good Lor’, what value can I put on them? I never had them published, modern stuff and classical stuff. They’re worth only the paper they’re written on—for the Salvage Campaign! Look here,’ he decided whimsically, ‘I’ll make a present of my life work to my country, I’ll claim nothing. And if that isn’t patriotism, I dunno what is!’ He roared with good-natured laughter and the clerk seemed rather to admire him, he hadn’t liked the look of him at first, people rarely did.

‘Very well, sir,’ he said. ‘This is the lot, then.’

‘Yes. We only rented the house. I’ve got all I can think of in the list. Tots up to a jolly old four hundred and seventy-eight quid. And I’m not cheating you,’ he challenged.

He hadn’t cheated at all. He’d been warned all round: ‘They aren’t giving full value, you know. I should pile it up a bit. After all, remember you’ve got to wait till after the war—twenty years’ time!’

Roars of laughter.

When they wrote and asked him to accept two-thirds of his claim, he accepted at once, regardless of genuine loss, and also the loss of his music. Who cared? There was three hundred odd quid to look forward to after the bally old war, if we won, what, and if one lived through the night’s blitz. It was comfortable and one had never been fussy. Not for shillings and pence. It was the general idea of wide security, no more shabbiness, that was what one hungered for. A chap wanted something really substantial. No more of this bloody messing about. A really decent house, cottage perhaps, but in town, of course, you could have your huntin’, fishin’ and shootin’; a cottagey house in Knightsbridge or Belgravia, yes, Belgravia (what was left of it), or else a really decent flat. That was the ticket.

Lying flat on his divan, and plotting the demise of Mr Watson, he tried to work out how much money he must get before he could chuck the game. It was really easier to deal with one or two of his dear old lady clients, they were gullible and often fell for him, and they had pots of dough. But he was through with killing women. It had been frightful, one never thought of ugly detail. Watson was a bit of a sly customer, but that rather gave it a fillip and made it more sporting. To get him to sign the bally policy would be tricky enough, and then there was the office to think about. He would have to kill Watson the same day, or at any rate the next day, before the office could write and confirm things. And what were the office going to say? ‘You’re a lucky chap, aren’t you, Mr Bowling? Most astonishing bit of luck, what?’ Yes it wasn’t going to be too simple, was it. There were mugs about, but the office weren’t mugs, and Mr Watson wasn’t a mug. Had he had some gin, he would have thought queerly: ‘What does it matter, anyway? If I’m caught, I am! Who cares? … I’d rather like to be tried at the Old Bailey, honestly I would!’ He heard himself assuming gin and thinking this—and wondered why, and if he really meant it deep down. Men are queer things, he thought. He whispered it to the empty room. ‘Men are queer things.’ Then he whispered: ‘How much money shall I want, to make life real and worth while, to get stuff published, you can get these things done if you can dangle a bag of gold in the right quarters? How many must I kill?’ He was vague. He thought he’d better try and get hold of ten thousand pounds, but it sounded such a large sum, when you were more used to odd ten bob notes. Money bored him and never stayed in his mind for long. Detail bored him too. It ought to be easy for the police, he thought. If they can’t spot me, they’ll never spot anyone. He forgot about money and the details of Watson’s murder and suddenly thought: ‘By jove, can I remember all my compositions? What a sweat, writing them out again? I’m not as energetic as I was.’ Mr Bowling was thirty-seven. On the day he murdered Mr Watson in Fulham, he was thirty-eight. At Queenie’s that same night, when she asked him what sort of a birthday he had had, he roared with laughter. But she commented that his hands were clammy.

His hands went clammy when anything really moved or excited him; it was nothing. Nerves, you called it. On his wedding day they’d been clammy, and on his first day at his public school. When his father had died, a week before that fourteenth birthday, his hands had turned clammy while he thought how unfortunate it was, now he was stuck with his stepmother, who loathed him. There were two kinds of stepmothers—which people tended to forget—the brilliantly successful, and the sadistically cruel. She was one of the latter, or he would not have criticised her for loathing him. Well, they loathed each other, there was a polite and very strained tolerance. His father had been vague as his son still was, and had left no will, so stepmother collared everything. She was a woman of ‘ideas,’ so she let him carry on with the public school education, but she packed him off to live permanently with a relative who had a house where the school was. She wasn’t a bad old girl and was fond of the bottle. He infinitely preferred it to being with his stepmother. A severe and rather cruel snag was the enforced severance from his sister, they were genuinely fond of each other, and she was the only real affection in his life then or now. She ran away from home, married and died in childbirth, but she was as real to him now as if she was still bobbing about in the sordid world, especially when he had a go at the Moonlight Sonata. She’d stand by the piano, nearly enough, and he’d smile sadly at her and talk to her. Anyone coming in thought he was nuts. At school they thought he was nuts, he would do mad things, it was really in order to try and become popular, he had what was called an inferiority complex, a silly but useful phrase meaning he’d been kicked around as a child, mentally or physically, and hadn’t found his feet yet; perhaps he wouldn’t find his feet until he was forty or so, or at all, a chap like that naturally needed help. He needed love. It was no good sneering at it, it just showed your bally ignorance. Well, which was worse, to have that, or to have a superiority complex? The first suited creative art quite well—you could work ferociously in the dark, without an audience and in time maybe get away with it, emerging to find your complex gone; the second suited actors and politicians, you needed all the ego and conceit you could manage—and Heaven help you if you couldn’t get away with it then. At school he would do whatever the other chaps dared him, like climbing up the tower, or creeping past the Housemaster’s bedroom to tap on the servant’s door and moan: ‘Whoooooo!’ like a ghost. When she screamed, and he got caught and flogged, he showed his marks proudly and roared with laughter. He had rather a big head, like a tadpole, and rather a pink face. The other chaps admired him, in a way, he had guts, was generous when he had anything to be generous with, but they didn’t ‘like’ him. He didn’t make a friend. He was mostly to be seen sitting over a magazine, beaming round hopefully to see if he was in favour today or not. He was hopeless at maths, good at French, plucky at boxing and swimming and P.T., a good long-distance runner, and oddly religious. His music master took a fancy to him, but it was difficult because the old chap had peculiar pawing habits with boys. It was dangerous to be up there with the bellows. ‘Bowling,’ he liked saying, ‘you’re a nice boy, I like you. You should learn to play the organ.’ This he did, with easy agility, and giggling with laughter when he was kissed and fondled, it was all so silly. He composed an organ solo which was performed on Speech Day, a huge moment in his life. He beamed round at everyone that day with much success, and he heard Colton Major, a scraggy youth he had always hated, saying to his mother:

‘That’s Bowling, he wrote it, I was telling you, mater! He’s really rather decent!’

Later, in fun, he got hold of scraggy Colton in the bushes and put a hand behind his neck and turned his scraggy frame round. It was easy. He put his hand over Colton’s mouth, and rather close to his nose, and it was amusing to hear Colton’s smothered screams. They were more like squeals. His face turned a dusky red, and then very slightly black. He thought he’d better let go.

Colton stood panting and gasping for breath.

‘You are a … swine, Bowling,’ he panted.

‘I suppose I am.’

‘… Why did you do that?’

‘I dunno. Because we’re leaving this term! Some such vague reason!’

‘You are a queer fellow. I think you’re a cad. You might have killed a man.’

‘What of it?’

‘It would have been murder.’

‘Well, there’s worse things than murder, Colton? Cheating. And running down a man’s parents. Things like that.’

‘I shan’t speak to you again,’ Colton panted and decided. ‘For the rest of our time here.’

Bowling roared with laughter.

In bed that night he was in the dock. He was smiling confidently and the jury were looking at him, all thinking:

‘He’s not guilty. Can’t you see—he’s a gentleman.’

The judge liked him too.

But the evidence went against him, and although he and the judge had gone to the same school (he was Mr Justice Colton), he put on the Black Cap and sentenced him to be hanged by the neck. It didn’t matter much, everyone knew he was not the usual criminal type, and when the last hours came and there was no reprieve there was still Angel to come and say goodbye to him, for she loved him.

Angel had lovely fair hair and warm ways with her. She was too lovely to be touched, even if you married her. You just sat at her feet, and only just dared to stroke her like a cat.

CHAPTER III

ANGEL went to the high school up the road. The boys got speaking to her over the wall. She had long golden hair and a lacrosse stick and a blue gym dress. One day Bowling trailed her all the way home, but she was too wonderful to talk to, he was too frightened, it was much safer to talk to God. So he trailed the two miles back and went into the chapel and prayed. He was afraid to pray in the proper pew, in case any of the chaps thought him a goody-goody, so he went up to the organ-loft and pretended he was about to play the organ—which he could not do in any case unless somebody worked the bellows. He felt God was real, an actual person, and that He was sorry for having to make people come down here for seventy years or so—less if you deserved it—as a sort of obscure punishment. Bowling could never see that death was a hard thing, despite all the beauties and happinesses which were to be found here; how could it be anything but a real ease from hard labour and worry, with our wars and our struggles? Yet there were people afraid of it. He honestly was not afraid of it, and he saw some vast scheme behind it all, which our inadequate mentalities were unfitted to imagine. There was some very good reason for suffering and hardship, we should probably never know what it was, we were perhaps not meant to. We just had to get along as we thought best, and try not to feel too tired after a bit. He early saw that love was the thing, marriage the nearest approach to happiness while we were here. He modelled this idea on Angel, the little girl over the wall. Up in the chapel he felt glad he had never thought or said coarse things about her, like the other chaps did, and he prayed to have somebody like that for himself. He was hungry for love, spiritual love, and loving God didn’t seem quite adequate, you wanted long, feminine, golden hair to stroke. He hadn’t even had a mother to love. She had quickly died. ‘At the sight of you, I expect,’ his stepmother had jested, a jest which hurt, as it was meant to. He grew up worried about his looks, trying to think he looked all right. He was afraid: ‘Nobody will love me, I’m afraid!’ That was why he smiled and laughed such a lot; hoping people would think he was nice.

‘Hallo,’ he always said, smiling broadly. He rubbed his hands together slowly. ‘Nice to see you! By jove, what?’

People were either embarrassed, or bored.

‘O, good morning, Mr Bowling. How are you?’

Not: ‘How are you?’

Except Queenie. She was different.

Queenie hated prudes. She’s had lots of men, and was even courageous about the colour bar. She’d give you Hell if you started up that topic. She said it was just as bad as the Nazis’ race creed. Humanity was the thing, we were all flesh and blood, and either our flesh and blood was feeling pretty good, or it was feeling pretty bad, and if the latter you should do something about it for folks. She got stranded for cash when she was in her ’teens and answered a friendship advertisement. ‘And I’ve been friendly ever since,’ she challenged. ‘So what?’ She liked to wink. ‘Finally I ran into a bit of regular money and married it. So what? My heart’s in the right place?’

He didn’t bump into Queenie and her crowd until he was about thirty. He’d had a pretty sordid time until then. He left public school with literally nothing. The Great War—so called—was over, and now it was the bitter, workless peace.

Work? There was no work. Unless you were a factory hand, or a grocer, or a machine tool maker.

The only faint possibility for a gentleman was a frightful thing called Salesmanship.

When he was desperate, he got on to this. Writing music? ‘Don’t make me laugh,’ he said to everyone. ‘It’s who you know—not what you know.’ He was a fairly good pianist, but he went to agents in vain. As for selling anything!

‘This won’t do,’ he thought, shabby and hungry. ‘Is this all my education means?’

He wished he’d been apprenticed to a garage all those school years. Mending punctures and things.

He had a peep down the Morning Post. There was nothing. Yes, there was, there was Salesmanship. Vacuum cleaners. Trade journals. Itinerary for housewives. Doors slammed in your face, Margate, Sheffield, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells. You could have it. There was no food in it, no clothes, no beer, no fags, no pictures, no women.

Life was complete Hell. Only those who had been through it knew what complete Hell on earth it really was, to an educated man with a sense of humour, a sense of patience, and a sense of God—which meant a sense of courage. And an artistic man, at that, whose mind and heart responded to the hidden chords of good music.

He would lie on his back on shabby divans and think about it. He’d try to laugh.

‘It’s no bally good giving in, you know? No blessed good at all, don’t you know! What?’

He first met Queenie in a pub. It was the Plumber’s Arms off Ebury Street. She wasn’t married then, she was friendly. He only had fourpence, what was the good of keeping it? He’d just tumbled on to the insurance racket, commission only, and maybe things would soon brighten up a bit. He digged up the road a bit, a bed-and-breakfast place, where he owed five weeks’ rent, but the old girl saw he was a gentleman and honest and down on his luck. She said openly she liked his smile and his laugh. Still, things couldn’t go on like this, you know, what? He saw Queenie looking at him and smiling. He smiled too, but regretted she would be unlucky if she wanted a drink. She was a bit blowsy, but she had a nice face and a smooth skin. She used the usual technique and said hadn’t she seen him somewhere before? He said the usual, yes, where was it now, but hastily adding he was flat broke, he was terribly sorry. ‘That’s all right, my dear,’ she said at once, ‘you must have one with me. Double Haig?’

‘I say, doubles, eh?’ he queried, wishing she’d buy a double sandwich instead.

‘Why not?’ she said sympathetically.

He saw her give his clothes a polite once-over.

‘Married?’ she said.

‘Yep,’ he said.

They got talking. With some people it was easy as winking. He told her about his marriage, how he’d cleared out, and how he already felt beaten and ready to go back.

‘I miss my piano. And the carpet,’ he laughed.

‘Where?’

‘Oh, Fulham.’

‘Poor old you.’

‘It’s hers, you see. Nearly everything. It was her money when we got married, that was my big mistake. She’s a lady, but she’s odd. Oh, I dunno. I was only twenty-one.’

‘Oh!’

‘She’s a bit older than me, quite a bit. Her parents cut her off, didn’t like me. She drags it up. I’m never allowed to forget. She goes on and on. Year after year, you know. I dunno, at last I blew right up in the air. You have to, sooner or later, don’t you?’

He laughed.

‘Let’s have another,’ she said.

He laughed again. Very ashamed, he went pink and said, ‘My dear, quite honestly, will you buy me a sandwich?’

She got half a whisky bottle, a couple of quarts of Bass, some fags, a cigar and marched him out.

‘There’s food at home. Come along.’

‘You’re a darling. This is ripping. Oh, my God, I feel a complete cad.’

‘You dry up.’

‘You’re a perfect pet.’

‘It’s in here …’

‘I wish there’d be a bally war or something, what?’

He laughed and she laughed and they stumbled up the narrow stairs to the top floor. It was rather theatreish, the hangings were like red plush. There was a not unpleasant suggestion of onions. There were two rooms, overcrowded with furniture and clothes chucked about, and the bath was in the kitchen with a board on it, the board crowded with vegetables and things. She showed the geyser, saying she’d given it a proper old polish this morning, and he could have a bath later on, just as he liked. She slipped into a white dressing gown affair and he sat smoking while she shoved something in the oven. When she finished that he gave her a kiss and they stood smiling at each other, she standing, he sitting on the edge of the bath, sort of amused, rueful expressions saying: ‘This old world, what can you do with it, short of making a complete hash of it?’ When he’d eaten they got talking about prudery and hypocrites, and discussing what the devil sin really was, where it began and where it ended, and what morals really were, poor old Hatry got landed, while old So and So, a complete rogue if ever there was one, remained M.P. for West Ditherminster, with packets of dough in armaments. Then they got down to whether, once agreed what sin was, you got punished for it on this earth—or later. It was very absorbing, and had always fascinated him very particularly; but Queenie dropped asleep on the sofa with his arm round her warm, plump body, and as she didn’t believe in God it was unlikely they would ever reach a conclusion. Being strong as a lion, despite all the undernourishment he had gone through, he carted her into bed and got himself undressed. The effort upset him strangely, but she was dead out, so he knelt by the bed and stared at her, quaintly saying the Lord’s Prayer out loud. The stuff she put on her hair was a bit faded at the roots, but she looked fair and he thought of Angel again. When he got into bed, she didn’t leave much room, and he had to get out to go and switch off the light. After that, he had to get out again twice in the night, forgetting the light both times, so the night was like a kind of steeple chase, treading over Queenie’s plump body, and trying not to kneel on her stomach in the dark. He made love to her in the morning when she woke up, a sudden impulse it was, and an impatient one, and afterwards he felt a bit worried. But she said: