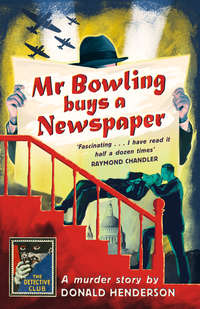

Mr Bowling Buys a Newspaper

Mr Bowling kept going.

‘By jove, really, how interesting,’ when being told about various bugs which ate leaves and so on. ‘Well, I’m blowed, what?’

‘I spray them,’ Mr Watson went on, endlessly.

Mr Bowling was wondering whether Mr Watson’s teeth would be likely to fall out, they might get to the back of his throat, and choke up the epiglottis. It might not look like murder, then.

The conversation veered round towards the blitz again.

‘Yes,’ Mr Watson said, ‘I was very shocked indeed to hear about your poor wife.’

‘Oh, well …’

‘I know what it’s like. I lost my wife suddenly one Saturday afternoon,’ he said, rather as if he’d taken her shopping, and it had happened that way.

‘Really?’

‘A bus …’

‘I say! I’m sorry, a beastly thing, that!’

‘But these things happen! Sad! Sad! But we’ve all got to go sometime.’

‘That’s true enough.’

‘Well, now, come into the dining room. There are various things to go into. And I expect you want my signature.’

They went into the dining room. It was very neat, and there was a picture of Mr Watson’s married daughter sitting in a deck chair at Margate and showing the most hideous legs. She really looked a corker. There was a plant in the firegrate, and on the table were Mr Watson’s pens and bits of blotting, all very fussy and neat, everything at right angles to everything else. He was like an old hen with his things. He sat busily down in his salt-and-pepper suit and started frowning about his money and his policies and his views on the Stock Exchange in general. The moment he saw the policy Mr Bowling had planned to try and get him to sign, he seized it in his bony fingers and stared.

Mr Bowling got to his left side, a little behind him.

‘Whatever’s this?’ Mr Watson exclaimed. ‘This won’t do at all,’ he said, and suddenly tore it up into little pieces.

He turned round towards Mr Bowling as if for another form, and Mr Bowling put his thick hand out. He suddenly and rather thoughtfully put his hand on Mr Watson’s moustache, and pressed Mr Watson’s head back so that it rested on his own chest, and the chair tilted and came back, and he quite easily dragged Mr Watson backwards out of sight of the little bay window. He felt the back of his legs touching the red plush settee, and he allowed himself to say quietly: ‘Take it easily, then it won’t take at all long,’ to Mr Watson, whose expression, if it was possible to judge it, was that of a startled child being forced to play a game he had never played before, and didn’t really like.

Mr Watson poised in mid-air, on the tilted chair, but generously supported in every possible way by his companion, over-toppled the chair, which fell on its side with a mild bump. Some footsteps went up the road, and some footsteps came down the road.

Mr Watson had started to do extraordinary things with his hands. He seized Mr Bowling’s two ears, and contrived to give a very sharp and fairly prolonged twist to them. After that, he transferred his grip to Mr Bowling’s hair.

When that had but little effect, he started up a bit of a spluttering, covering Mr Bowling’s hand with spittle, and managing to grip in pincer movements at the backs of Mr Bowling’s hams.

There was quite a strong smell of geraniums, Mr Bowling noticed. It was not unpleasant. He thought several times: ‘What is actually happening? Am I dreaming?’

If he was dreaming, the dream continued.

The red plush settee again touched the backs of his calves. Mr Watson was frantically trying to get freed by a rapid series of shakes. He shook his stomach to and fro, and wriggled. Mr Bowling permitted himself to sit and get a better purchase, as it occurred to him that Mr Watson might be going to take rather longer than Ivy had. Mr Watson’s grey eyes began to show a neat mixture of astonishment and increasing terror, and he wriggled and spreadeagled his long pepper-and-salt legs, and managed to get a bit of breath in through his nose. Mr Bowling tightened the vacuum there, and pressed hard at the moustache, which was a trifle ticklish. Mr Watson’s attitude was a trifle obscene. Various things began to pass rapidly through Mr Bowling’s brain, which had begun to be astonishingly clear. He thought, well, this was rather amazing, he hadn’t wasted much time, so he was doing it after all—and why? There was no money in it, none whatever: now, why was that thought such a comfort? Why? Why, because, one supposed, fraud was rather a shabby thing; even if it was money belonging to a company worth millions, it was still fraud. And another thing, did it occur to one that somebody else may be at that moment in the little house? In the kitchen, perhaps? And another thing: where did one get this method from? It was pretty effective. Burke and Hare used to do it. Had one read of it first, or thought of it first and then read of it? The subconscious was a very interesting thing. Did people realise that places were sometimes haunted by the future—as well as by the past? Did one …?

There was no stopping the amazing pace of his thoughts. His life raced backwards and forwards. He was holding Colton behind the chapel. Now it was Mr Watson again. Now it was poor Ivy.

Now it was Mr Watson.

Why was it? Why was he doing it? And why did he now know he was going to do several more murders? Murders? Don’t call them that—such a vulgar word.

Then it came to him swiftly and clearly that he was doing it because he was so thoroughly disappointed in himself and his life; he wanted to be caught.

He wanted it.

Suddenly Mr Watson managed to give a violent lurch.

But it didn’t mean anything. His face was black, his head had sunk, his body gave a kind of twist and Mr Bowling held him a few moments more and then allowed it to collapse face downwards into the red cushion. He pulled up the sagging knees and dumped them on the settee and stood up. He was panting.

Presently, Mr Bowling straightened his collar, took up his papers and hat and went out of the house.

He smiled in the summer sunshine and decided to go to the pictures.

He went to the Metropole in Victoria, somehow he felt more at home in Victoria than Fulham, it was near to Queenie, where he would go later on. For the present, he wanted the quiet and the dark, but not the quiet and the dark of solitude.

He wanted to think things out.

He presently decided that he was a fox. He wanted the chase, he expected to be caught, and he even wanted that. He wanted the hunters to have every chance.

He was one of life’s misfits. A bungler with money, and with life; just a poor devil with an artistic soul, ruined by education. Cursed or blessed with a weak heart, and thereby useless to his country in matters to do with killing; just a knock-about. Yes, yes, he thought in the pictures, the sooner they catch me, the better: though not a soul will ever understand. Not a soul.

He sat in the pictures with his eyes shut, in very severe mental agony.

Half way through the big picture, he fell fast asleep. When he woke up, people were roaring with laughter. He roared with laughter too until tears came.

Then he slipped out and hurriedly bought a newspaper.

CHAPTER V

QUEENIE was waiting for him in the new flat she and Rodney had recently chosen. They still stuck to Belgravia, it was a habit, it was home, they knew all the locals.

Locals were their background.

Queenie was wife-hunting for Mr Bowling. ‘Dear Bill,’ as she called him. ‘I must have a scout round,’ she told Rodney in her pleasant way.

‘I doubt if you need trouble,’ Rodney said. He took what he called rather a poor view of that Bowling fellow.

‘Whyever?’ Queenie teased him now and again.

‘I hate cynics,’ Rodney commented, and he argued with Queenie that there was too much of the cynic about that Bowling fellow. She wouldn’t agree, saying that ‘old Bill simply wants understanding.’

‘Maybe I don’t understand him, then!’

‘And he’s going through something,’ she frowned. She was vague about this, usually tossing it aside with a laugh.

Rodney liked to say that Bill had been rather rude to him about the Civil Service being what he called ‘departmental minded’, licking each other’s boots in a time-serving way in the interests of advancement, and afterwards running each other down behind each other’s backs. All individuality, Mr Bowling pronounced, was unhesitatingly sacrificed in the interests of pay day. On top of this, that fellow Bowling had got a bit tight one night and it had got back to him that Bowling thought him ‘typical’ of the M.O.I. If you offered yourself for a war job there, (Bowling reported) they put you through an exam, and only when you passed it suddenly thought of asking you about your grade of health. If you said you were Grade One, Two or Three, they said, sorry, can’t employ you unless you’re Grade Four, old chap, and looked brightly at you, almost proud of the waste of time and paper involved in the preliminary correspondence and the exam! And Bowling had said: ‘The perfect job for dear old Rodney—suit him down to the ground.’

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов