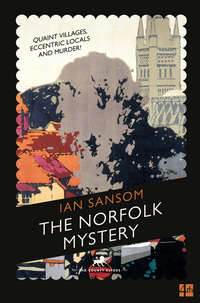

The Norfolk Mystery

‘Sit,’ he said. His voice was pleasant, like an old yellow vellum – the voice of a long-accomplished public speaker. It was a voice thick with the authority of books. I sat in the leather armchair facing the desk.

From this position I could see him cross and uncross his legs as he sat at the table. He had improvised for himself, I noted, as a footrest a copy of Debrett’s Peerage, Baronetage, Knightage and Companionage, illustrated with armorial bearings – half-calf, well rubbed – his restless feet jogging constantly upon it. He wore a pair of highly polished brown brogue boots of the kind gentlemen sometimes wear for country pursuits; it was almost as if he were striding through his typing, the sound of which filled the room like gunfire. He continued to type and did not speak to me for what seemed like a long time, yet I did not find this curious silence at all unsettling, for what somehow emanated from him was a sense of complete calm and control, of light, even, a quality of personality of the kind I had occasionally encountered at Cambridge, and in Spain, among both men and women of all classes and types, a personality of the sort I believe Mr Jung calls the ‘extravert’, a character somehow unshadowed as many of us are shadowed, someone fully realised and confident, completely present, blazing. Another word for this kind of determining character, I suppose, is ‘charisma’, and my interviewer, whether knowing it or not, seemed to epitomise this elusive and much prized quality. He had ‘it’, whatever ‘it’ is – something more than a twinkle in the eye. He also seemed, I have to admit, deeply familiar, but I could not at this stage have identified him precisely.

‘You are?’ he asked, in a momentary pause from his labours.

‘Stephen Sefton.’

He glanced at what I assumed were my employment particulars set out on the top of a pile of papers by his right elbow.

‘Sefton. Apologies. Must finish an article,’ he said. He had a large egg-timer beside the Underwood, whose sands were fast running out. ‘Two minutes till the post.’

‘I see,’ I said.

‘You can type?’ he asked, continuing himself to beat out a rhythm on the keys.

‘Yes.’

Rattle.

‘Shorthand?’

Ping.

‘I’m afraid not, sir, no.’

‘I see. Too much of a’ – carriage return – ‘hoity-toity?’

‘No, sir, I don’t think so.’

Rattle. ‘You’d be prepared to learn, then?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Good.’ Back space.

‘Photography. You can handle a camera?’

‘I’m sure I could try, sir.’

‘Hmm. And Cambridge, wasn’t it? Christ’s College.’

‘Yes, sir.’

Ping.

‘Which makes you rather over-qualified for this position.’

‘Sorry, sir.’

Rattle.

‘No need to apologise. It’s just that none of the other candidates has been blessed with anything like your educational advantages, Sefton.’ Carriage return.

‘I have been very … lucky, sir.’

‘Not a varsity type among them.’

‘I see, sir.’

Ping.

‘Curious. Perhaps you can tell me about it.’

‘About what, sir?’

‘What went wrong.’

‘What went wrong? I … I don’t know what went wrong.’

‘Clearly. Well, tell me about the college then, Sefton.’

‘The college?’

‘Yes. Christ’s College. I am intrigued.’

‘Well, it was very … nice.’

‘Nice?’

He paused in his typing and peered dimly at me in a manner I later came to recognise as a characteristic sign of his disbelief and despair at another’s complete ignorance and lack of effort. ‘Come on, man. Buck up. You can do better than that, can’t you?’

I was uncertain as to how to respond.

‘I certainly enjoyed my time there, sir.’

‘I believe you did enjoy your time at college, Sefton. Indeed, I see by your abysmal degree classification that you may have enjoyed your time there rather more than was advisable.’

‘Perhaps, sir, yes.’

‘Too rich to work, are we?’

‘No, sir,’ I replied. I was not, in fact, rich at all. My parents were dead. The family fortune, such as it was, had been squandered. I had inherited only cutlery, crockery, debts, regrets and memories.

He looked at me sceptically. And then tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, tap, and then a final and resounding tap as the sands of the timer ran out. A knock came at the door.

‘Eleven o’clock post,’ said my interviewer. ‘Enter!’

A porter entered the dark room as my interviewer peeled the page he had been typing from the Underwood, shook it decisively, folded it twice, placed it in an envelope, sealed it and handed it over. The porter left the room in silence.

My interviewer then checked his watch, promptly upended his egg-timer – ‘Fifteen minutes,’ he said – sat back in his chair, stroked his moustache, and returned to the subject we had been discussing as if nothing had occurred.

‘I was asking about the history of the college, Sefton.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t know much about the history, sir.’

‘It was founded by?’

‘I don’t know, sir.’

‘I see. You are interested in history, though?’

‘I have taught history, sir, as a schoolmaster.’

‘That’s not the question I asked, though, Sefton, is it?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Schooled at Merchant Taylors’, I see.’ He brandished my curriculum vitae before him, as though it were a piece of dubious evidence and I were a felon on trial.

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Never mind. Keen on sports?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘No time for them myself. Except perhaps croquet. And boxing. Greyhound racing. Motor racing. Speedway. Athletics … They’ve ruined cricket. And you fancy yourself as a writer, I see?’

‘I wouldn’t say that, sir.’

‘It says here, publications in the Public Schools’ Book of Verse, 1930, 1931 and 1932.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘So, you’re a poet?’

‘I write poetry, sir.’

‘I see. The modern stuff, is it?’

‘I suppose it is, sir. Yes.’

‘Hm. You know Wordsworth, though?’

‘Yes, sir, I do.’

‘Go ahead, then.’

‘Sorry, sir, I don’t understand. Go ahead with what?’

‘A recitation, please, Sefton. Wordsworth. Whatever you choose.’

And he leaned back in his chair, closed his eyes, and waited.

It was fortunate – both fortunate, in fact, and unfortunate – that while at Merchant Taylors’ I had been tutored by the late Dr C.T. Davis, a Welshman and famously strict disciplinarian, who beat us boys regularly and relentlessly, but who also drummed into us passages of poetry, his appalling cruelty matched only by his undeniable intellectual ferocity. If a boy failed to recite a line correctly, Davis – who, it seemed, knew the whole of the corpus of English poetry by heart – would literally throw the book at him. There were rumours that more than one boy had been blinded by Quiller-Couch’s Oxford Book of English Verse. I myself was several times beaten about the ears with Tennyson and struck hard with A Shropshire Lad. By age sixteen, however, we victim-beneficiaries of Dr Davis’s methods were able to recite large parts of the great works of the English poets, as well as Homer and Dante. We had also, as a side effect, become enemies of authority, our souls spoiled and our minds tainted for ever with bitterness towards serious learning. But no matter. At my interviewer’s prompting I began gladly to recall the beginning of the Prelude, as familiar to me as a popular song:

Oh there is blessing in this gentle breeze,

A visitant that while it fans my cheek

Doth seem half-conscious of the joy it brings

From the green fields, and from yon azure sky.

These words seemed to please my interviewer – as much, if not more so than they would have done Dr Davis himself – for he leaned forward across the Underwood and joined me in the following lines:

Whate’er its mission, the soft breeze can come

To none more grateful than to me; escaped

From the vast city, where I long had pined

A discontented sojourner: now free,

Free as a bird to settle where I will.

He then fell silent as I continued.

What dwelling shall receive me? in what vale

Shall be my harbour? underneath what grove

Shall I take up my home? and what clear stream

Shall with its murmur lull me into rest?

The earth is all before me. With a heart

Joyous, nor scared at its own liberty,

I look about; and should the chosen guide

Be nothing better than a wandering cloud,

I cannot miss my way. I breathe again!

‘Very good, very good,’ pronounced my interlocutor, waving his hand dismissively. ‘Now. Canada’s main imports and exports?’

This sudden change of tack, I must admit, threw me entirely. I rather thought I had hit my stride with the Wordsworth. But it seemed my interviewer was in fact no aesthete, like our beloved Dr Davis, nor indeed a scrupuland like the loathed Dr Leavis, the man who had quietly dominated the English School at Cambridge while I was there, with his thumbscrewing Scrutiny, and his dogmatic belief in literature as the vital force of culture. Poetry, I had been taught, is the highest form of literature, if not indeed of human endeavour: it yields the highest form of pleasure and teaches the highest form of wisdom. Yet poetry for my interviewer seemed to be no more than a handy set of rhythmical facts, and about as significant or useful as a times table, or a knowledge of the workings of the internal combustion engine. I had of course absolutely no idea what Canada’s main imports and exports might be and took a wild guess at wood, fish and tobacco. These were not, as it turned out, the correct answers – ‘Precious metals?’ prompted my interviewer, as though a man without knowledge of such simple facts were no better than a savage – and the interview took a turn for the worse.

‘Could you give ten three-letter nouns naming food and drink?’

‘Rum, sir?’

‘Rum?’ My interviewer’s face went white, to match his moustache.

‘Yes.’

‘Anything else, Sefton – anything apart from distilled and fermented drink?’

‘Cod?’

‘Yes.’

‘Eel?’

‘Satisfactory, if curious choices,’ my interviewer concluded. ‘You might more obviously have had egg or pea.’

‘Or pig, sir?’

‘A pig, I think you’ll agree, is an animal, Sefton. It is not a foodstuff until it has been butchered and made into joints. A pig is potential food, is it not?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Tell me, Sefton, are you able to adapt yourself quickly and easily to new sets of circumstances?’

‘I believe I am sir, yes.’

‘And could you give me an example?’

I suggested that in my work as a schoolmaster I had encountered numerous occasions when I had been required to adapt to circumstances. I did not explain that one such occasion was when I had been found in a compromising situation with the headmaster’s wife. Fortunately, my interviewer did not ask for further elaboration and we returned promptly to questions of more import: the lives of the saints; folk customs; Latin tags; the classification of plants and animals. During the conversation he would glance concernedly at the egg-timer on his desk and thrum his fingers on the table, as though batting against time itself.

‘You seem to have a reasonably well-stocked mind, Sefton.’

‘Thank you, sir.’

‘As one would expect. Languages?’

‘French, sir. Latin. Greek. German. Some Spanish.’

‘Yes. I see you were in Spain.’

‘I was, sir.’

‘A Byron on the barricades?’

‘I never considered myself as such, no, sir.’

‘No pasaran.’

‘That’s correct, sir.’

‘Unable to fight in Spain, I learned Spanish instead.’

We spoke for a few minutes in Spanish, my interviewer remarking in a rudimentary way upon the weather and enquiring about the prices of rooms in hotels.

‘Your Spanish is certainly satisfactory, Sefton,’ he said. ‘Good. Do you have any questions about the position?’

‘Yes, sir.’

My main question, naturally, was what the position was and what it might entail – I still had no clear idea. I cleared my throat and tried to formulate the question in as inoffensive a manner as possible. ‘I wondered, sir, exactly what it might … entail, working as your assistant?’

My interviewer looked at me directly and unguardedly at this point, in a way that made me feel exceedingly uncomfortable. He had a way of looking at you that seemed violently frank, as though willing you to reveal yourself. And when he spoke he lowered his voice, as though confiding a secret.

‘Well, Sefton. I hope I can be honest with you?’

‘By all means, sir.’

‘Good.’ He carefully fingered his moustache before going on. The light of the lamps was reflected in his eyes. ‘I believe, Sefton, that there is a terrible darkness deepening all around us. We face not un mauvais quart d’heure, Sefton, but something more serious. Do you understand what I am saying?’

‘I think so, sir.’

I was not at all sure in fact if the serious darkness he was referring to was the darkness I had encountered in Spain, and which haunted me in my dreams, or if it were some other, ineffable darkness of a kind with which I was not familiar.

‘I think perhaps you do see, Sefton.’ He stared hard at me, as though attempting to penetrate my thoughts, his voice gradually rising in volume and pitch. ‘Anyway. It is my intention to shed some light while I may.’

‘I see, sir.’

‘I hope that you do, Sefton. It has been my life’s work. What I see around me, Sefton, is the world as we know it rapidly disappearing: the food we eat; the work we do; the way we talk; the way we consort ourselves. Everything changing. All of it about to go, or gone already: the miller, the blacksmith, the wheelwright. Destroyed by the rhythms of our machine age.’ He paused again to stroke his moustache. ‘It has been my great privilege, Sefton, in my career to visit the great countries and cities of the world: Paris, Vienna, Rome. I intend my last great project to be about our own enchanted land.’

‘England, sir.’

‘Precisely. The British Isles, Sefton. These islands. The archipelago. Before they disappear completely.’

‘Very good, sir.’

He fell silent, staring into the middle distance.

I felt that my question about the job had not been answered entirely or clearly, and realised I might need to prompt him for a more direct answer. ‘And what exactly would the person appointed by you be required to do, sir, on your … project?’

‘Ah. Yes. What I need, Sefton, is someone to write up basic copy that I shall then jolly up and make good. The person appointed would also be required to make arrangements for travel and accommodation, and to assist me in all aspects of my researches on the project as I see fit.’

‘I see, sir.’

‘I shan’t give you a false impression of my daily rounds, Sefton. There is no glamour. It is tiresome work requiring long hours, endurance and determination.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘And do you think you’re up to such a task?’

‘I believe so, sir.’

‘Are you married, Sefton?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Engaged to be married?’

‘No, sir.’

‘A homosexual?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Pets?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Good. We’ve plenty of those already. You don’t mind dogs?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Terriers?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Cats?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Birds?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Aversions or allergies to any kind of animals?’

‘Not that I know of, sir.’

‘And you are not in current employ?’

‘No, sir.’

‘Good. So you’d be able to start immediately?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Very well.’

My curiosity had certainly been piqued by my interviewer’s description of his enterprise, but after several rounds of questioning I was still keen to know more about the details. I made one more bid for clarity. ‘Can I ask, sir, exactly what the project is to be?’

‘The project?’ He sounded surprised, as though the nature of his work was widely known. ‘A series of books, Sefton, called The County Guides. A complete series of guides to the counties of England.’

‘All of them, sir?’

‘Indeed.’

‘How many counties are there?’

‘Schoolmaster, aren’t we, Sefton?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Well, then? Let me ask you the question: how many counties are there?’

‘Forty? thirty-nine?’

‘Thirty-nine. Exactly.’

‘So, thirty-nine books?’

‘We may also include the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey, Sefton. In which case there shall be forty-one.’

‘An … ambitious project then, sir.’ It struck me, in fact, not so much as ambitious as the very definition of folly.

‘In a life, Mr Sefton, of finite duration I can’t imagine why anyone would wish to embark on any other kind of project. Can you?’

‘No, sir.’

‘I intend the County Guides as nothing less than the new Domesday Book. I shall be going out into England with my assistant to find all the good things and to put them down.’

‘Only the good, sir?’

‘The books are intended as a celebration, yes, Sefton.’

‘Works of … selective amnesia, then, sir?’

My interviewer frowned deeply at this untoward remark. ‘Among those I would call the “not-so-intelligentsia”, Sefton, I know there to be an inclination to talk down our great nation. Are you one such down-talker?’

‘I like to think I’m a realist, sir.’

‘As am I, Sefton, as am I. Which is why I am undertaking this project. You may wish to reflect, sir, that you are of a generation that may live to see the year 2000, from which distant perspective you will be viewing a nation doubtless very different from that which you see around you now. It is my desire merely to set down a record of this place before its roots are cut and its sap drained, and the ancient oaks are felled once and for all. I do not wish England – our England – to be unknown by future generations. Do you understand, Sefton?’

‘I think so, sir.’

‘Good.’ He shifted in his seat and he glanced around the room, as though someone were among us. ‘Because I believe I can feel the chilly hand of fate coming upon us, Sefton. The County Guides I hope shall be clarion calls: they may be memorials.’ He paused momentarily for reflection upon this profundity.

‘And how long do you imagine this great enterprise will take, sir?’

‘I intend to have completed the series by the end of the decade, Sefton.’

‘By 1940?’

‘1939 I think you’ll find marks the end of the decade, Sefton. 1940 forms a part of the next, surely?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘So, 1939’s our deadline.’

‘A book on every county? By 1939?’

‘On every county, yes, Sefton. And by 1939. A celebration of England and the Englishman. From the wheelwrights of Devon to the potters of the north, from the shoe-makers of Northampton to the chair-makers of High Wycombe, the books will be—’

‘The chair-makers of High Wycombe?’

‘Renowned for its chair-making, Sefton. Do you know nothing of the English counties? Anyway, as I was explaining. I envisage this not merely as my magnum opus, but as a magnum bonum. De omnibus rebus, et quibusdam aliis—’

‘But that’s … dozens of books a year, sir.’

‘Precisely. Which is why I need an assistant, Sefton.’

‘I see, sir.’ The sheer scale of the task seemed ludicrous, lunatic. Which is, I think, what appealed: my own life had already reached the brink.

‘I was ably assisted for a number of years, Sefton, by my daughter and by my late wife. But my daughter is … maturing. And so I find myself … seeking to employ another. Anyway,’ he announced, as the final grains of sand gathered to announce the passing of fifteen minutes, ‘tempus fugit.’

‘Irreparable tempus,’ I said.

He glanced at me approvingly. ‘The hour is coming, Sefton, when no man may work.’

‘Indeed, sir.’

And at this he rose from his seat and walked towards the door. I followed. ‘I do hope that you don’t imagine that because of our surroundings today’ – he gestured into the gloom around him – ‘that we shall be going in for ritzy social gatherings, Sefton.’

‘No, sir. Not at all.’

‘Or chatterbangs. No swirl of the cocktail eddies here.’

‘I understand, sir.’

‘Good. Well. That’ll be all, I think, Sefton. I’ll send a telegram.’ He went to shake my hand.

‘Actually, sir. I have one more question, if I may.’

‘Yes?’

There was one question that remained unanswered, and which I was keen to have resolved before leaving the room.

‘Might I ask your name, sir?’

‘My name? My apologies. I thought you knew, Sefton. My name is Morley. Swanton Morley.’

CHAPTER THREE

SWANTON MORLEY.

Anyone who grew up in England after the Great War will naturally be familiar with the name, a name synonymous with popular learning – the learning, that is, of the kind scorned by my bloodless professors at Cambridge, and adored by the throbbing masses. Swanton Morley was, depending on which newspaper you read, a poor man’s Huxley, a poor man’s Bertrand Russell, or a poor man’s Trevelyan. According to the title of his popular column in the Daily Herald he was, simply, ‘The People’s Professor’.

Morley’s story is, of course, well known: a shilling life will give you all the facts. (I rely here, for my own background information, on Burchfield’s popular The People’s Professor, and R.F. Bolton’s Mind’s Work: The Life of Swanton Morley.) Born in poverty in rural Norfolk, and having left school at fourteen, Morley began his career in local newspapers as a copy-holder. Coming of age at the turn of the century, he had ‘stepped boldly forward’, according to Bolton, ‘to become one of the heroes of England’s emancipated classes’. By the time he was twenty-five years old he was the editor of the Westminster Gazette. ‘Unyielding in his mental habits’, in Burchfield’s phrase, Morley had grown up the only child of elderly, Methodist parents. He was a man of strict principles, known for his temperance campaigns, his fulminations against free trade, and his passionate denunciations of the evils of tobacco. He was also an amateur entomologist, a beekeeper, a keen cyclist, a gentleman farmer, a member of the Linnean Society and the Royal Society, the founder of the Society for the Prevention of Litter – and the chairman of so many committees and charitable organisations that Bolton provides an appendix in order to list them and all his other extraordinarily various and energetic outpourings of the self.

On the day of my interview, however, I knew absolutely none of this.

Like most of the British public, I knew not of Morley the man, but of Morley’s books. Everyone knew the books. Morley produced books like most men produce their pocket handkerchiefs, his rate of production being such that one might almost have suspected him of being under the influence of some drug or narcotic, if it weren’t for his reputation as a man of exemplary habits and discipline. Morley had published, on average, since the early 1900s, half a dozen books a year. And I had read not one of them.