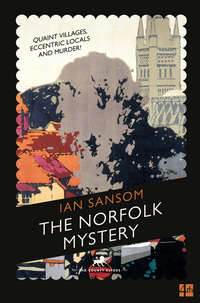

The Norfolk Mystery

She glanced at me, her Picasso-like profile all the more striking in motion.

‘Do you drive, Sefton?’

‘I do.’

She then seemed to be waiting for me to ask something back; she was that kind of woman. The kind who asked questions in order to have them asked back, using men essentially as pocket-mirrors.

‘This is a lovely car,’ I said.

‘Oh, this? Yes. Father’s mad on cars. He’s got half a dozen, you know. Loads and loads. The bull-nosed Morris Cowley, with a dickey seat – dodgy fuel pump. And the ancient Austin, Of Accursed Memory. The Morris Oxford, with beige curtains at the windows; sometimes he’ll take a nap in it in the afternoons. It’s terribly sweet really.’

‘Yes.’

‘He can’t drive, though, of course. And he has all these sorts of crazy ideas. He thinks cars run better at night-time – something to do with the evening air. Claims it’s scientific. Absolute clap-trap, of course. But this is my favourite,’ she continued, stroking the steering wheel. ‘It’s a Lagonda,’ she said, stressing the second syllable, in the Italian fashion. ‘Isn’t it a lovely word?’

‘Quite lovely,’ I said.

‘Lagonda,’ she repeated. She clearly liked the idea of Italian. Or Italians. ‘Only twenty-five of them made. Designed by Mr Bentley himself, I believe. Herr Himmler has one in Germany. Harmsworth. King Leopold of the Belgians. I think you’ll find that ours is one of the only white Lagonda LG45 Rapides in England.’

‘Really?’ I said. She seemed to be awaiting congratulations on this fact. I declined to compliment, and instead silently admired the car’s upholstery and its fine walnut dashboard.

Saxlingham outdistanced, we were now beyond signposts, in deep English country.

‘She handles very well,’ she continued. ‘The car, I mean, Sefton.’ That ridiculous eyebrow again. ‘One of Father’s concessions to modernity. He won’t buy us proper plumbing, but anything that gets him from here to there more quickly he’s happy to fork out for! Honestly! It’s the production version of the Lagonda race car, you know. She’s really the last word.’

‘In what?’

‘Cars, silly! Top speed of a hundred and five miles per hour. Would you like me to show you?’

‘No, thank you, miss,’ I said, suspecting that we were already not far from such a speed. ‘I’ll take your word for it.’

‘Oh come on, Sefton,’ she said, fiercely revving the car’s engine. ‘Don’t you enjoy a little adventure?’

‘I used to,’ I said.

‘What? Lost your taste for it?’

‘Possibly, miss, yes.’

‘Oh dear. Well, perhaps I’ll be able to revive your flagging interest then, eh?’ And with this she leaned forward eagerly in her seat, stamped on the accelerator, and we began tearing up the roads.

‘You’re not scared are you?’ she called, as our speed increased.

But I now found her absurd flirtatious antics too wearisome to respond to at all, and simply gazed at the hedgerows speeding past inches from the car, which was spitting up stones and dirt – we were now driving along a single-track road that had clearly been made for horses’ hoofs rather than high-speed Lagondas.

We breasted a small hill and began careering down the other side, approaching a bend at both unsuitable angle and speed.

‘Slow down, miss,’ I said sharply.

‘What?’

‘Slow down.’

As we sped unwisely towards the bend she turned and looked at me and there was a look in her eye that I recognised – the same look I had seen in men’s eyes in Spain; and the look they must have seen in mine. Desperation. Fear. Joy. A shameless, stiff, direct gaze, challenging life itself. Terrifying.

She was understeering – out of ignorance, I suspected, rather than daring – as we approached the bend, and I found myself reaching across her, grabbing the wheel and tugging it towards me, attempting to correct the angle and bring the car in more tightly.

‘Look out!’ she screamed, as we swept down upon the bend, the rear of the Lagonda swinging out from behind us, her foot slamming down instinctively on the brakes.

‘Don’t brake!’ I screamed – I knew it would throw the car – and grabbed down at her ankle and pulled it up, reaching down with my other hand to apply a little pressure in order to transfer weight to the front.

It worked. Just.

We skidded to a halt, engine and tyres smoking, my head first in her lap and then juddering into the Lagonda’s pretty dashboard. The engine cut out.

‘Oh!’ she yelled. ‘You maddening man! What on earth do you think you’re doing?’

‘What do you think you’re doing?’ I yelled back.

At which challenge she threw her head back and laughed, a great throaty, hollow laugh, as though the whole thing were a mere prank she’d rehearsed many times. Which she may have.

‘What am I doing? I’m living, Sefton! How do you like it, eh?’

I sat up, straightened myself, opened the car door and climbed out.

‘What are you doing?’ she called.

‘I’m getting out here, miss, thank you,’ I said.

‘But you can’t!’

‘Yes I can.’ I began walking on ahead. ‘I’ll find my own way now, thank you, miss.’

‘How dare you!’ I could hear the stamp of her pretty little foot. ‘Get back in here now! Now!’

The rich and exotic beauty of the English countryside

I walked on ahead, feeling calm.

‘Sefton!’ she called. ‘Did you hear me, man? Get back in here, now.’

Then, realising that I had no intention of obeying her orders and that she had indeed lost control of the situation, she promptly started up the still smoking engine, stamped her foot on the accelerator, and sped past, hooting the horn as she went.

‘See. You. Later. Sluggard!’ she called, snatching triumph with one last toss of her head. The look in her eyes remained with me for some time.

It was a trek to the Morley house. My head was throbbing. My foot was sore. I stopped off at a cottage on the road to a place called Blakeney, asking for directions, and the old cottager came out – a fine country figure, rigged out in greasy waistcoat and side whiskers of the variety people used to call ‘weepers’ – and pointed back the way I’d come. ‘But I’m terrible blind,’ he warned, as I departed. I wasn’t sure if he meant literally, or if it was some amusement of his. Whichever, he sent me the wrong way, and it was long past supper time when I eventually arrived, sans suitcase, sans pills, sans everything.

A thin new moon was set high in the sky.

I felt wretched. Outcast. Like an apparition. Or a newborn child.

CHAPTER FIVE

THE FAMOUS MORLEY HOUSE, St George’s – described by Burchfield as ‘a true Englishman’s castle’ and by Bolton as ‘his legacy in bricks and mortar’ – was at that time only twenty years old, Morley himself having overseen its construction. Some, I know, have written off the house as a work of Edwardian folly, others have celebrated it as a testament to a great Englishman’s passions. But it was far too dark for me to make a judgement that first evening. Country dark is a darkness far beyond what city-dwellers imagine and at St George’s, at night, one could almost swim in the thick black swirling around one. I passed up the driveway, between imposing entrance gates – atop which, in glinting moonlight, sat St George on the one hand, dragon dutifully slain, and the Golden Hind on the other – and up past what I assumed to be a small lake, and walked, exhausted, between an avenue of old trees and finally up stone steps to the house, with statues of Britannia and lions rampant guarding the entrance. The door, an anachronistic mass of carved oak – like something by Ghiberti for a cathedral – stood open.

A true Englishman’s castle

‘Good evening!’ I called, peering into the house’s gloom. ‘Mr Morley? It’s Sefton, sir. I’m sorry I—’

For half a moment there came no reply and then suddenly in the entrance hall there was cacophony, the whole house, it seemed, screaming out in agony in response to my call. The noise was that of cold-blooded murder. Startled, I drew back, almost tripping down the steps, my heart racing. I shut my eyes and actually thought I might be sick – the maddening Miriam, no food, no pills, only a little tobacco. I had slipped back into a dream of Spain. But then, after several minutes, when the incredible noise continued and no one came, and with no intention of retracing my weary footsteps back down the driveway and all the way back to misery and London, I peered cautiously into the hall.

There were, thank God, no demons. It was no dream. The grand entrance hall to St George’s – as readers of Burchfield will recall – had been set up as a kind of a zoo and a natural history museum. The walls all around were hung with glass cases and shelves holding displays of skulls and bones, and turtle shells, and sets of teeth and taxidermised beasts: one case seemed to comprise a collection merely of snouts. And then below these displays of their ancestors and relatives were the living animals themselves, a literal tableau vivant. Rather poor taste, I thought – keeping animals in a kind of animal catacomb. Drawing my eye, directly opposite the great doorway, was the celebrated aquarium, set up on a simple wooden plinth, the whole thing not less than the height of a man and perhaps more than twenty feet across – nothing like it outside the major aquariums of Europe – and designed as a kind of Alpine garden, thick with pebbles and vegetation, and with brightly coloured fish weaving their way through crystal-clear water and decorative stonework. I was drawn towards this extraordinary, oddly luminescent sight and moved mesmerised towards it, noticing a clipboard attached to the plinth, which seemed to record feeding times and observations. ‘Dytiscus,’ read the notes. ‘Dragon-fly larvae?’ But I was distracted by all this for only a moment before there came a sudden whoosh and swooping above my head, as a couple of – could they have been? Neither Burchfield nor Bolton make mention of them – jackdaws made their presence known. As my eyes became accustomed to the gloom I glanced all around me and made out among the extraordinary menagerie a goose, a cockatoo, dogs, shrews – and, set apart from the other animals, where one might otherwise expect what-nots or a display of family silver, a large, roomy cage containing what I thought was probably a capuchin monkey. At the sight and sound of me, the monkey raised herself, looked lazily around, and then lay back down to sleep.

As I reeled and tottered slightly, disorientated from these incredible sights and the incessant noise – ‘a place of wonder’, according to Burchfield, though he evidently had never come upon it unprepared, and at night – I thought I heard the faint tapping of a typewriter coming from elsewhere in the house, and knowing that Morley himself could not be far away I rushed down a long corridor lined with thousands of books and bound piles of newspapers, pursued by various loping and persistently swooping creatures, until I burst in upon a kitchen. Which, like the entrance hall, both was and was not what one might usually hope and expect.

St George’s was not so much a home as a small, privately funded research institute. The kitchen resembled a laboratory. Indeed, I realised on that first night, judging merely by the ingredients, chemicals and equipment lining the shelves, that it was both kitchen and laboratory, home for both amateur bacteriologist and amateur chef. Up above the fine Delft tiles and the up-to-the-minute range and the sink, up on the walls, were pretty collections of porcelain and china, flanked by row upon row of frosted and dark brown bottles of chemicals. And recipe books. And below, at a vast oak refectory table scarred with much evidence either of meals or experiments, sat Morley, my very own Dr Frankenstein, in colourful bow tie, slippers and tartan dressing gown.

I breathed a sigh of relief.

The cockatoo came and settled on his shoulder, two terriers at his feet. The jackdaws circled once, then fled away. Cats, geese – and a peacock! – warmed and disported themselves by the range.

‘Ah, good, Sefton,’ he said, glancing up from what I now regarded as his customary position behind a typewriter, surrounded by books, and egg-timer at his elbow. ‘You found us then?’

‘Yes, sir,’ I said, panting slightly, regaining my composure.

‘Glass of barley water?’ He indicated a jug of misty-looking liquid by his elbow. It was his customary evening treat.

‘No, thank you.’ I was rather hoping for strong drink.

‘And you met my daughter, I hear.’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘She’s rather eccentric and strong-willed, I’m afraid.’

‘That’s … perhaps one way of describing it, sir, yes.’

‘Yes. Women are essentially wild animals, Sefton. That’s what you have to remember.’

‘Well …’

‘Untameable,’ he said. ‘Not like these.’ He stroked a terrier at his side, gestured at the bird, the cats. The peacock. ‘And what with the bobbed hair, I have to say, about as unlovely as a docked horse. After her mother died – my wife – we tried her at a convent school in Belgium. No good. No good at all. Wild animals,’ he repeated. ‘Scientifically proven, Sefton. I’ve made quite a study of animal behaviour, you know.’

‘Yes, I was … admiring your …’

‘Menagerie?’

‘Yes. And the aquarium. On the way in.’

‘Good. Yes. We’ve an aviary as well. And a terrarium, of course. And then there’s the farm. Model farm only. But. You’re familiar with ethology, Sefton?’

‘I don’t think I am, actually, sir, no.’

‘Sit down, sit down. No need to stand on ceremony now.’ I perched precariously on a round-backed chair by the table, its wicker seat half caved in and piled with books. ‘Ethology,’ continued Morley. ‘Study of gestures, Sefton. Or rather, interpretation of character through the study of gesture. Applies in particular to animal behaviour.’

As usual, I wasn’t sure if I was expected to answer, or to listen. But then Morley went on, kindly resolving my dilemma for me.

‘Can also be applied to humans, of course. So you’d have to ask, what was she signalling to you?’

‘Who, sir?’

‘My daughter, Sefton. She’s told me all about it. The journey.’

‘I see, sir.’

‘This is where our friend Herr Freud goes wrong, I believe. Confusing mental qualities with behaviour. Most of our fraying is a kind of animal suffering, you see. I do wish psychoanalysts would spend more time studying animal communication.’

‘I’m afraid I don’t quite—’

‘I’ll be honest with you, Sefton. You’ll need to watch her carefully. Attend to her gestures. And the eyes – everything is in the eyes. The face, as you know, speaks for us. We must learn to read it. Which is becoming more difficult all the time. With women’s faces, I mean. Foreheads tightened. Creases erased. Extraordinary. You’ve read about this? Young women having their bosoms unloaded and … uploaded? American, of course. Jewesses do it with their noses, I believe. Dreadful. Nothing to be ashamed of, surely? And many women now of course supporting their entire families, you know. Businesswomen. Materfamilias. Noblesse industrielle. Waitresses in dinner jackets in London – it’s a fashion from France.’

‘Is it, sir?’

‘The feminine question, it seems, no longer requires a masculine answer, Sefton.’

As usual, Morley’s mind seemed to be spinning up and around and away from the conversation into realms where it was difficult to follow. Fortunately, he brought himself back down to earth – I was far too tired to have tried dragging him down myself.

‘Anyway, we’re setting off tomorrow, Sefton.’

‘Tomorrow, sir?’

‘Yes. Research for the first book. The County Guides. Remember? Book one. Numero uno. Un. Eins. In Polish, do you know?’

‘No, I’m afraid …’

‘Numbers one to ten, in the major Indo-European languages? Essential knowledge, I would have thought, for every man, woman and child in this day and age.’

‘No, I’m afraid I … Jeden?’ I hazarded a guess.

‘Excellent!’ said Morley. ‘I knew I’d made the right choice with you, Sefton.’

I silently thanked my father for all the ambassadors who’d trooped through our drawing room all those years ago, jabbering in their languages and teaching us children cards, much to my mother’s dismay.

‘Anyway, all the arrangements have been made. You’ll have the cottage on your return, but for tonight you have a room upstairs. The upper room. I hope it’s sufficient.’

‘I’m sure it’ll be more than sufficient, sir.’

‘Good. And there’s no need to call me sir.’

‘Very well, sir.’

‘You may call me Mr Morley.’

‘Very good, Mr Morley.’

‘We’ll be leaving by 7 a.m. I like to get an early start. Now. You’ll be wanting some supper?’

‘Well …’

‘The maid has set something out in your room, I think. You’re not a vegetarian?’

‘No.’

‘Marvellous. All very well for Hindus, for whom I have the very greatest respect, I should say. But, the boiled beef of England, isn’t it? Cold meats for you, mostly, I think. Seed cake. You know the sort of thing. And you’re travelling light, I see. Good good. Russian tea?’ he asked, indicating a tall glass of brackish-looking liquid by the typewriter, which one might have mistaken for typewriter fuel. ‘I developed a passion for it after my time in Russia.’

‘No. I’m fine, thank you.’

‘Well, good. That’s us then. You go on ahead. Make yourself at home. I’ve an article to finish here. Chronicle. On the history of the folk harp. Fascinating subject. One can see in its history the spread of certain common craft skills across civilisations. I’ll see you first thing.’

‘Certainly.’ I made back towards the door, avoiding animals, in the hope of finding my room without further adventure. ‘Just one question, Mr Morley, if I may.’

‘Yes. Of course, Sefton.’

‘Which county will we be beginning with tomorrow, sir?’

‘I thought we’d start close to home, Sefton. With God’s own county.’

‘Yorkshire?’

‘Norfolk. “I am a Norfolk man and glory in being so.” Who said that, Sefton?’

‘I don’t know, Mr Morley.’

‘Nelson, of course! Horatio Nelson! Adopted son of the county, whose native sons include …?’

‘Hmm. I—’

‘The aboriginally Norfolk, Sefton? The autochthones? The Sparti, as it were? The old Swadeshi, as our friend Mr Gandhi might have it? Come, come.’

‘I’m sorry, I—’

‘People from round here?’

‘I don’t know, Mr Morley, I’m afraid.’

‘Boadicea? Elizabeth Fry? Thomas Paine? Dame Margery Kempe? Sir Robert Walpole! You’ll need to be reading up on your Norfolk folk, Sefton. The character and the characters of Norfolk, Sefton, that’s what we’re after! Plenty of flavour. Plenty of seasoning. I’ve left some of the relevant maps and guides in your room, so you can get started tonight.’

‘Very good, Mr Morley.’

‘Seven, no later,’ he called, as I left the kitchen and he returned to his work, almost as in meditation, animals happily around him, tap-tap-tapping at the typewriter.

CHAPTER SIX

‘WAS IT EDWARD IV who breakfasted on a buttock of beef and a tankard of old ale every morning?’ asked Morley.

‘It may have been, sir.’

‘Well, we don’t.’

‘No,’ I agreed.

‘Cup of hot water with a slice of lemon. Bowl of oatmeal,’ said Morley, tapping his spoon decisively on the side of his bowl. ‘Sets a man up for the day. Full of goodness, oatmeal. Steel-cut. Pure as driven snow.’

‘Pass the sugar, would you?’ said Miriam. ‘Indispensable, wouldn’t you say, Sefton? Utterly tasteless without, isn’t it? Like eating gruel.’

‘Gruel? Gruel?’ said Morley, before embarking on a short excursion on the history of the word, punctuated by Miriam’s protests and my own occasional weary agreements.

It was the morning after the night before, and I was enjoying my first taste of breakfast in the dining room at St George’s, which was not a household, I came to realise, that liked to ease its way into the day. There was neither a halt nor indeed even a pause in the relentless clamour of argument and quarrelling that echoed around the place like trains at a continental railway station. The conversation – to quote Sir Francis Bacon, or possibly Dr Johnson, or Hazlitt, certainly one of the great English essayists, who Morley liked to quote at every opportunity, and who I now, in turn, like to misquote – was like a fire lit early to warm the day and once lit was inextinguishable. Even when engaged in apparently casual conversation, Morley and his daughter exchanged verbal thrusts and parries that could be shocking to the outsider. For his part, Morley was not a man who brooked much disagreement, and his daughter was not a woman who liked to be bested in argument: and so the sparks would fly. All houses, of course, have an atmosphere – some pleasant, some not so pleasant, and some merely strange, no matter how humble nor how grand. The atmosphere of St George’s was one of a noisy Academy, presided over by Socrates and his rebellious daughter.

‘Sleep well?’

‘He’s not a child, Father. “A dry bed deserves a boiled sweet.”’

‘Sorry, I—’

‘Ignore her, Sefton. She only does it to provoke.’

‘Are you feeling provoked, Sefton?’ asked Miriam.

‘Erm. No. I don’t think so.’

‘Good,’ said Morley. ‘Dies faustus, eh? Dies faustus! All set?’

‘I think so, Mr Morley.’

‘Good, good. First day. Gradus ad Parnassum. Miriam will be driving us, in the Lagonda.’

‘Very well.’

‘Until you get the hang of it.’

‘Get the hang of it!’ snorted Miriam.

‘Anyway, I thought it would be nice for you to accompany us on the first outing. And I’ll need to brief Mr Sefton properly.’

‘Brief him? It’s hardly a military operation, Father.’

‘Have you exercised, Sefton?’

‘Not this morning, sir, no.’

‘Pity. Never mind. No time now. But in future I’ll expect you to be in fine fettle for our little trips. You’re welcome to use the swimming pool, you know. Down by the orchard.’

‘Thank you.’

‘Not at all. You have a bathing gown?’

‘No, I’m afraid my clothes … I left my luggage on the train.’

‘I see.’ He eyed my blue serge suit with a tailor’s precision, his eyes like tiny chalks.

‘Oh. We’ll have to see what we can do. I think we might have some clothes that fit you. Miriam, do you think?’ They both looked me up and down.

‘About the same height,’ said Miriam.

‘Same build,’ agreed Morley. ‘You know where the clothes are?’

‘Yes, Father.’ Miriam sighed. There was an awkward – and unusual – silence. Miriam poured more coffee, the remains of the coffee from a flask.

‘Anyway,’ said Morley. ‘Bathing suit. I’ll lend you one of mine. Fifty lengths, I’d say? Controlled Interval Method of training I prefer. We need you in tip-top shape. This is not going to be a holiday, you know.’