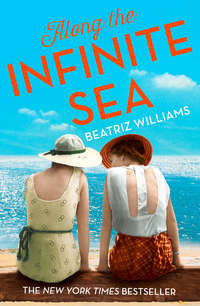

Along the Infinite Sea: Love, friendship and heartbreak, the perfect summer read

ANNABELLE

Antibes • 1935

1.

But long before the Ritz, there was the Côte d’Azur.

My father had used the last of Mummy’s money to lease his usual villa for the summer, perched on a picturesque cliff between Antibes and Cannes, and such was the lingering glamor of his face and his title that everybody came. There were rich American artists and poor English aristocrats; there was exiled Italian royalty and ambitious French bourgeoisie. To his credit, my father didn’t discriminate. He welcomed them all. He gave them crumbling rooms and moderately fresh linens, cheap food and good wine, and they kept on coming in their stylish waves, smoking cigarettes and getting drunk and sleeping with one another. Someone regularly had to be saved from drowning.

Altogether it was a fascinating summer for a young lady just out of a strict convent school in the grimmest possible northwest corner of Brittany. The charcoal lash of Biscay storms had been replaced by the azure sway of the Mediterranean; the ascetic nuns had been replaced by decadent Austrian dukes. And there was my brother, Charles. I adored Charles. He was four years older and terribly dashing, and for a time, when I was young, I actually thought I would never, ever get married because nobody could be as handsome as my brother, because all other men fell short.

He invited his own guests, my brother, and a few of them were here tonight. In the way of older brothers, he didn’t quite worship me the way I worshipped him. I might have been a pet lamb, straying in my woolly innocence through his fields, to be shooed gently away in case of wolves. They held their own court (literally: they gathered in the tennis courts at half past eleven in the morning for hot black coffee and muscular Turkish cigarettes) and swam in their own corner of the beach, down the treacherous cliff path: naked, of course. There were no women. Charles’s retreat was run along strictly fraternal lines. If anyone fancied sex, he came back to the house and stalked one or another of my father’s crimson-lipped professional beauties, so I learned to stay away from the so-called library and the terrace (favored hunting grounds) between the hours of two o’clock in the afternoon and midnight, though I observed their comings and goings the way other girls read gossip magazines.

Which is all a rather long way of explaining why I happened to be lying on the top of the garden wall, gazing quietly toward the lanterns and the female bodies in their shimmering dresses, the crisp drunk black-and-white gentlemen, on the moonless evening they brought the injured Jew to the house.

At half past ten, shortly before the Jew’s arrival, I became aware of an immense heat taking shape in the air nearby. I waited for this body to carry on into the garden, or the scrubby sea lawn sloping toward the cliffs, but instead it lingered quietly, smelling of liquor and cigarettes. Without turning my head, I said, in English, “I’m sorry. Am I in your way?”

“I beg your pardon. I did not wish to disturb you.” The English came without hesitation, a fluid intermingling of High German and British public schools, delivered in a thick bass voice.

I told him, without turning my head, that he hadn’t. I knew how to kick away these unwanted advances from my father’s accidental strays. (The nuns, remember.)

“Very good,” he said, but he didn’t leave.

He occupied a massive hole in the darkness behind me, and that—combined with the massive voice, the hint of dialect—suggested that this man was Herr von Kleist, an army general and Junker baron who had arrived three days ago in a magnificent black Mercedes Roadster with a single steamer trunk and no female companion. How he knew my father, I couldn’t say; not that prior acquaintance with the host was any requirement for staying at the Villa Vanilla. (That was my name for the house, in reference to the sandy-pale stone with which it was built.) I had spoken to him a few times, in the evenings before dinner. He always sat alone, holding a single small glass of liquor.

I rose to a sitting position and swung my feet down from the wall. “I’ll leave you to yourself, then,” I said, and I prepared to jump down.

“No, please.” He waved his hand. “Do not stir yourself.”

“I was about to leave anyway.”

“No, you mistake me. I only came to see if you were well. I saw you steal out here and lie on the garden wall.” He gestured again. “I hope you are not unwell.”

“I’m quite well, thank you.”

“Then why are you here, alone?”

“Because I like to be alone.”

He nodded. “Yes, of course. This is what I thought about you, when you were playing your cello for us the other night.”

He was dressed in a precise white jacket and tie, making him seem even larger than he did by day, and unlike the other guests he had no cigarette with him, no glass of some cocktail or another to occupy his hands, though I smelled both in the air surrounding him. The moon was new, and I couldn’t see his face, just the giant outline of him, the smudge of shadow against the night. But I detected a slight nervousness, a particle of anxiety lying between me and the sea. I’d seen many things at the Villa Vanilla, but I hadn’t seen nervousness, and it made me curious.

“Really? Why did you think that?”

“Because—” He stopped and switched to French. “Because you are different from the others here. You are too young and new. You shouldn’t be here.”

“None of us should be here, really. It is a great scandal, isn’t it?”

“But you particularly. Watching this.” Another gesture, this time at the terrace on the other side of the wall, and the shimmering figures inside it.

“Oh, I’m used to that.”

“I’m very sorry to hear that.”

“Why should you be sorry? You’re a part of it, aren’t you? You came here willingly, unlike me, who simply lives here and can’t help it. I expect you know what goes on, and why. I expect you’re here for your share.”

He hesitated. There was a flash of light from the house, or perhaps the driveway, and it lit the top of his head for an instant. He had an almost Scandinavian cast to him, this baron, so large and fair. (I pictured a Viking longboat invading some corner of Prussia, generations ago.) His hair was short and bristling and the palest possible shade of blond; his eyes were the color of Arctic sea ice. I thought he was about forty, as old as the world. “May I sit down?” he asked politely.

“Of course.”

I thought he would take the bench, but instead he placed his hands on the wall, about five feet down from me, and hoisted his big body atop as easily as if he were mounting a horse.

“How athletic of you,” I said.

“Yes. I believe firmly in the importance of physical fitness.”

“Of course you do. Did you have something important to tell me?”

He stared toward Africa. “No.”

Someone laughed on the terrace behind us, a high and curdling giggle cut short by the delicate smash of crystal. Neither of us moved.

Herr von Kleist sat still on the brink of the wall. I didn’t know a man that large could have such perfect control over his limbs. “My friend the prince, your father, I saw him quite by chance last spring, at the embassy in Paris. He told me that I must come to his villa this summer, that I am in need of sunshine and amitié. I thought perhaps he was right. I am afraid, in my inexperience, I did not guess the meaning of his word amitié.”

“Your inexperience?” I said dubiously.

“I have never been to a place like this. Like the void left behind by an absence of imagination, which they are attempting, in their wretchedness and ignorance, to fill with vice.”

“Yes, you’re right. I’ve just been thinking exactly the same thing.”

“My wife died eleven years ago. That is loss. That is a void left behind. But I try to fill that loss with something substantial, with work and the raising of our children.”

What on earth did you say to a thing like that? I ventured: “How many children do you have?”

“Four,” he said.

I waited for him to elaborate—age, sex, height, education, talents—but he did not. I stared down at the gossamer in my lap and said, “Where are they now?”

“With my sister. She was the one who insisted I go, and so I did. I regretted it the instant I walked through the door. There was a woman in the hall, a dark-haired woman, and she was smoking a cigarette and using the most unkempt language.”

“Probably Mrs. Henderson. She’s desperately rich and miserable. An American. She sleeps with everybody, even the servants.”

“It grieves me to hear this.”

“I’m afraid it’s true.”

“No, not that it’s true. I do not give a damn—pardon, Mademoiselle—about Mrs. Henderson. It grieves me that you know this about her. That your family would allow you under the same roof as such a woman as that.”

“Oh, it’s not as bad as that. My father doesn’t allow me to mingle very much with his guests, except to entertain them with my cello after dinner. He doesn’t know what to do with me at all, really, since I left Saint Cecilia’s, and I’m too old for a governess.”

“He ought to send you to live with a relative.”

“I would run away. I’d return here.”

“Why? You will pardon my curiosity. Why, when you are not like them?”

“Why not? I’m like a scientist, studying bugs. I find them fascinating, even if I don’t mean to turn into a mosquito myself.”

Herr von Kleist had placed his hands on his knees, and as large as his knees were, his hands dwarfed them. “Mosquitoes. Very good,” he said gravely. “Yes, this is exactly what I imagined about you, when I saw you lying on the garden wall just now, observing the mosquitoes.”

We had switched back into English at some point, I couldn’t remember when.

I said, “Really, you shouldn’t be here. You should go home to your children.”

He made another one of his sighs, weary of everything. “You are the one who should leave. There is not much hope for us, but you can still be saved. This is not the place for you.”

I jumped down from the wall and dusted the grit from my hands. “I’d say there’s plenty of hope for you. You seem like a decent man. Anyway, this is the only place I know, other than the convent.”

“Then go back to your convent.”

I was about to laugh, and I realized he was serious. At least his voice was serious, and his eyes, which were sad and invisible in the darkness. “But I don’t want to go back.”

“No, of course you do not. You want to live. You are how old?”

“Nineteen.”

He made a defeated noise and slid down from the wall. “You think I am ancient.”

“No, not at all,” I lied.

“I’m thirty-eight. But that does not matter.” He picked my hand from my side and kissed it. “It is you who matter.”

He was drunk, of course. I realized it now. He was one of those lucky fellows who held it perfectly, without slurring a single word, but he was drunk nonetheless. There was the slightest waver in his titanic frame as he stood before me, engulfing my fingers between his two leathery palms, and there was that waft of liquor I’d noticed from the beginning. Who could blame him? It took such an unlikely amount of moral resolve to remain sober at the Villa Vanilla.

When I didn’t speak, he moved his heavy head in a single nod. “Yes. It is better this way. Nothing valuable is ever gained in haste.”

“Quite true,” someone said, but it wasn’t me. It was my brother, Charles, coming up behind me like a cat in the night, and before either of us had time to reflect on the silent surprise of his appearance, he had pried my hand from the grasp of Herr von Kleist and begged the general’s forgiveness.

An urgent matter had arisen, and he needed to borrow his sister for a moment.

2.

“Borrow me?” I jogged to keep up as my brother’s long legs tore the scrubby grass between the garden and the cliffs. “Are you short for poker?”

“Of course not.” He yanked the cigarette stub from his mouth and tossed it on the ground, into a patch of gravel. “What the hell were you doing with that Nazi?”

“Nazi? He’s a Nazi?”

“They’re all Nazis now, aren’t they? Pay attention, it’s the cliff.”

I wasn’t dressed for climbing. I gathered up my skirts in one hand. We started down the path, over the lip of the cliff, and the sea crashed in my ears. I followed the flash of Charles’s shoes just ahead. “What’s the hurry?” I asked.

“Just be quiet.”

The last of the light from the house had dissolved, and I began to stumble in the absolute blackness of the night. I had only the faint ghostliness of Charles’s white shirt—he had somehow shed his dinner jacket—to guide me, as it jerked and jumped about and nearly disappeared in the space before me. The toe of my slipper found a rock, and I staggered to the ground.

“What’s the matter with you?” Charles said.

“I can’t see.”

He swore and fumbled in his pockets, and a second later a match struck against the edge of a box and hissed to life. “My God,” I said, staring at Charles’s face in the tiny yellow glow. “Is that blood?”

He touched his cheek. “Probably. Look around. Get your bearings.”

I looked down the slope of the cliff, the familiar path dissolving into the oily night. “Yes. All right.”

The match sizzled out against his fingers, and he dropped it into the rocks and took my hand. “Let’s go. Try to keep quiet, will you?”

I knew exactly where I was now. I could picture each stone, each twist in the jagged path. Inside the grip of Charles’s hand, my fingers tingled. Something was up, something extraordinary—so extraordinary, my brother was actually drawing me under the snug shelter of his confidence. Like when we were children, before Mummy died, before we returned to France and went our separate ways: me to the convent, my brother to the École Normale in Paris. That was when the curtain had come down. I was no longer his co-conspirator.

But I remembered how it was. My blood remembered: racing down my limbs, racing up to my brain like a cleansing bath. Come down to the beach, I’ve found something, Charles would say, and we would run hand in hand to the gritty boulder-strewn cove near the lighthouse, where he might show me an old blue glass bottle that had washed up onshore and surely contained a coded message (it never did), or a mysterious dead fish that must—equally surely—represent an undiscovered species (also never); and once, best of all, there was a bleached white skeleton, half articulated, its grinning skull exactly the size of Charles’s spread hand. I had thought, We’re in trouble now, someone will find out, someone will sneak into the house and kill us, too, to eliminate the witnesses; at the same time, I had cast about for the glimpse of wood that must be lying half hidden in the nearby sand, the treasure chest that this skeleton had guarded with his life.

Now, as I stumbled faithfully down the cliff path in Charles’s wake, and my eyes so adjusted to the darkness that I began to pick out the white tips of the waves crashing on the beach, the rocks returning the starlight, I wondered what bleached white skeleton he had found for me tonight.

And then the path fell into the sand, and Charles was tugging me through the dunes with such strength that my slippers were sucked away from my feet. We made for the point on the eastern end of the beach, where the sea curled around a finger of cliff and formed a slight cove on the other side. There was just enough shelter from the current for a small boathouse and a launch, which the guests sometimes used to ferry back and forth to the yachts in Cannes or Antibes. I saw the roof now, a gray smear in the starlight. Charles plunged straight toward it, running now. The sand flew from his feet. Just before he ducked through the doorway, he stopped and turned to me.

“You did say you nursed in a hospital, right? At the convent? I’m not imagining things?”

“What? Yes, every day, after—”

“Good.” He took my hand and pulled me inside.

There were four of them there, Charles’s friends, two of them still in their dinner jackets and waistcoats. An oil lantern sat on the warped old planks of the deck, next to the nervously bobbing launch, spreading just enough light to illuminate the fifth man in the boathouse.

He sat slumped against the wall, and his bare chest was covered in blood. He lifted his head as I came in—the chin had been tucked into the hollow of his clavicle—and he said, in deep German-accented English, much like the voice of Herr von Kleist, only more slurred and amused: “This is your great plan, Créouville?”

3.

But his chest wasn’t injured. As I cried out and fell to my knees at his side, I saw that he was holding a thick white wad to his thigh, around which a makeshift tourniquet had already been applied, and that the white wad—a shirt, I determined—was rapidly filling with blood, like the discarded red shirts next to his knee.

“Actually, it seems to be getting better,” he said.

I adjusted the tourniquet—it was too loose—and lifted away the shirt. A round wound welled instantly with blood. I said, incredulous: “But it’s a—”

“Gunshot,” he said.

I pressed the shirt back into the wound and called for whisky.

“I like the way you think,” said the wounded man.

“It’s not to drink. It’s to clean the wound. How long ago did this happen?”

“About twenty minutes. Right, boys?”

There was a general murmur of agreement, and a bottle appeared next to my hand. Gin, not whisky. I lifted away the shirt. The flow of blood had already slowed. “This will sting,” I said, and I tilted the bottle to allow a stream of gin on the torn flesh.

I was expecting a howl, but the man only grunted and gripped the side of the leg. “He needs a doctor, as quickly as possible,” I said to the men. “Has someone telephoned Dr. Duchamps?”

There was no reply. I put my fingers under the injured man’s chin and peered into his eyes. His pupils were dilated, but not severely; he met my gaze and followed me as I turned my face from one side to the other. I glanced back at Charles. “Well? Doctor? Is he on his way?”

Charles crouched next to me. “No.”

“Why not?”

“Too much fuss. There’s someone meeting you on the ship.”

“Ship? What ship?”

The injured man said, “My ship.”

“You’re going with him,” said Charles. “You can still drive the launch, can’t you?”

“What?”

“You’re the only one who can do it. The rest of us have to stay here.”

“What? Why?”

“Cover,” said the injured man, through his gritted teeth.

I looked back down at the wound, which was now only seeping. Probably the bullet had only nicked the femoral artery, otherwise he would have been dead by now. He was a large man—not as large as Herr von Kleist, but larger than my brother—and he had plenty of blood to spare. Still, it was a close thing. My brain was sharp, but my fingers were trembling as I pressed the shirt back down. Another fraction of an inch. My God. “I don’t have the slightest idea what you mean,” I said, “and why not one of you perfectly able-bodied men can help me get this man to safety, but we don’t have a minute to waste arguing. Give him a fresh shirt. If he can hold it to his leg himself, I can take him to his damned yacht. It is a yacht, isn’t it?”

“Yes, Mademoiselle,” the man said humbly.

“Of course it is. And if the police catch up with us, what am I to say?”

“That you know nothing about it, of course.”

I took the fresh shirt from Charles’s hand and replaced the old; I took the man’s large limp hand and pressed it to the makeshift bandage. “I’ll take the gin. Charles, you put him in the launch.”

“You see?” said Charles. “I told you she was a sport.”

4.

On the launch, I took pity on the man and gave him the bottle of gin, while I steered us around the tip of the Cap d’Antibes and west toward Cannes, where his yacht was apparently moored. He took a grateful swig and tilted his head to the stars. The lantern sat at the bottom of the boat, so as not to be visible from shore.

“You are very beautiful,” he said.

“Stop. You’re not flirting with me, please. You came three millimeters away from death just now.” The draft was cool and salty; it stung my cheeks, or maybe I was only blushing.

“No, I am not flirting. But you are beautiful. A statement of fact.”

I peered into the dark sea, seeking out the distant harbor lights, smaller than stars on the horizon. The water was calm tonight, only a hint of chop. As if God himself were watching over this man.

“Am I allowed to ask your name?” I said.

He hesitated. “Stefan.”

“Stefan. Is that your real name?”

“If you call me Stefan, Mademoiselle, I will answer you.”

“I see. And what sort of trouble gets a nice man shot in the middle of a night like this, so he can’t see a doctor onshore? Argument at the casino? Is the other man perhaps dead?”

“No, it was not an argument in the casino.”

He tilted the bottle back to his lips. I thought, I must keep him talking. He has to keep talking, to stay conscious. “And the other man?”

“Hmm. Do you really wish to know this, Mademoiselle?”

“Oh, priceless. I’m harboring a criminal fugitive.”

“Do not worry about that. You will be handsomely rewarded.”

“I don’t want to be rewarded. I want you to live.”

He didn’t reply, and I glanced back to make sure he hadn’t fainted. I wouldn’t have blamed him, lighter as he was of a pint or two of good red blood. But his eyes were open, each one containing a slim gold reflection of the lantern, and they were trained on me with an expression of profound … something.

I was about to ask him another question, but he spoke first.

“Where did you learn to treat a wound from a gun, Mademoiselle de Créouville?”

“I’ve never even seen a wound from a gun. But the sisters ran a charity hospital, and the men from the village got in regular brawls. Sometimes with knives.”

“The sisters? You are a nun?”

“No. I was at a convent school. I’ve only just escaped. Anyway, they made us all work in the charity hospital, because of Christ tending the feet of the poor. Hold on!” We hit a series of brisk chops, the wake of some unseen vessel plowing through the night sea nearby. Stefan grunted, and when the water calmed and I could relax my attention to the wheel, I glanced back again to see that his face was quite pale.

He spoke, however, without inflection. “You have a knack for it, I think. You did not scream at the blood, as most girls would. As I think most men might.”

“I have a brother. I’ve seen blood before.”

“Ah, the dashing mademoiselle. You tend wounds. You drive a boat fearlessly through the dark. What sort of sister is this for my friend Créouville? He said nothing about you before.”

“He has successfully ignored me for the past half decade, since we were sent back to France after our mother died.”

“I am sorry to hear about this.”

I tightened my hands on the wheel and stared ahead. The pinpricks were growing larger now, more recognizably human. I hardly ever ventured into Cannes, and certainly not by myself, but I’d passed the harbor enough to know its geography. “Where is your ship moored?” I asked.

He muttered something, and I looked back over my shoulder. His eyes were half closed, his back slumped.