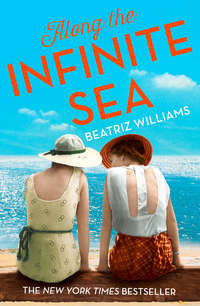

Along the Infinite Sea: Love, friendship and heartbreak, the perfect summer read

The woman stopped shrilling when she saw me. She was dressed in a long and shimmering evening gown, and her hair was a little disordered. There was a diamond clip holding back a handful of once-sleek curls at her temple, and a circle of matching diamonds around her neck. Her lipstick was long gone. Her eyes flicked up and down, taking me in, exposing the line of smudged kohl on her upper lid. “And who are you?” she asked, in haughty French, though I could tell from her accent that she was English.

“His nurse.”

“I must see him.”

I stood back from the door. “Five minutes,” I said, in my sternest ward sister voice, “and if you upset him even the smallest amount, if I hear so much as a single word through this door, I will open your veins and bathe in your blood.”

I must have looked as if I meant it, for she ducked through the door like a frightened rabbit, and when six minutes had passed without a single sound, I knocked briefly on the door and opened it.

Stefan lay quite still on the bed. His eyes were closed, and the woman’s hand rested in his palm. She was curled in the armchair—my armchair, I thought fiercely—and she didn’t look up when I entered. “He is so pale,” she said, and her voice was rough. “I have never seen him like this. He is always so vital.”

“As I said, he has lost a great deal of blood.”

“May I sit with him a little longer?”

She said it humbly, the haughtiness dissolved, and when she tilted her head in my direction and accepted my gaze, I saw a track of gray kohl running down from the corner of her eye to the curve of her cheekbone. She had dark blond hair the color of honey, and it gleamed dully in the lamplight. Her gown was cut into a V so low, I could count the ribs below her breasts. I looked at Stefan’s hand holding hers, and I said, “Yes, a little longer,” and went back out the door and down the narrow corridor to the stern of the ship, which was pointed toward the exposed turrets of the Fort Royal on the Île Sainte-Marguerite, where the Man in the Iron Mask had spent a decade of his life in a special isolated cell, though no one ever knew who he was or why he was there. Whether he had a family who mourned him.

4.

I had sent a note for Charles with the departing doctor, in the small hours of the morning, and I expected my brother any moment to arrive on the yacht, to assure himself of Stefan’s survival and to bring me home.

But lunchtime came and went, the disheveled blonde departed, and though someone brought me a tray of food, and a bowl of hot broth for Stefan, Charles never appeared.

Stefan slept. At six o’clock, a boat hailed the deck and the doctor’s head popped over the side, followed by his bag. The day had been warm, and the air was still hot and laden with moisture. “How is our patient this evening?” he asked.

“Much better.” I turned and led him down the hallway to Stefan’s commodious stateroom. “He’s slept most of the day and had a little broth.” I didn’t mention the woman.

“Excellent, excellent. Sleep is the best thing for him. Pulse? Temperature?”

“All normal. The pulse is slow, but not alarmingly so.”

“To be expected. He is an active man. Well, well,” he said, ducking through the door, “how is our intrepid hero, eh?”

Stefan was awake, propped up on his pillows. He shot the doctor the kind of look that parents send each other when children are present, and listening too closely. The doctor glanced at me, cleared his throat, and set his bag on the end of the bed.

“Now, then,” he said, “let us take a look at this little scratch of yours.”

On the way back to the boat, the doctor gave me a list of instructions: sleep, food, signs of trouble. “He is quite strong, however, and I should not be surprised if he is up and about in a matter of days. I shall send over a pair of crutches. You will see that he does not overexert himself, please.”

“I don’t understand. I had no expectation of staying longer than a day.”

The doctor stopped in his tracks and turned to me. “What’s this?”

“I gave you a message, to give to my brother. Wasn’t there a reply? Isn’t he coming for me?”

He pushed his spectacles up his nose and blinked slowly. The sun was beginning to touch the cliffs to the west, and the orange light surrounded his hair. The deck around us was neat and shining, bleached to the color of bone, smelling of tar and sunshine. “Coming for you? Of course not. You are to care for the patient. Who else is to do it?”

“But I’ll be missed,” I said helplessly. “My father— You must know who I am. I can’t just disappear.”

The doctor turned and resumed his journey across the deck to the ladder, where his tender lay bobbing in the Isolde’s lee. “My dear girl, this is nothing that young Créouville cannot explain. He is a clever fellow. No doubt he has already put about a suitable story.”

“But I don’t understand. What’s going on? What sort of trouble is this?”

“I don’t know what you mean,” he said virtuously.

“Yes, you do. What sort of trouble gets a man shot in the night like that, everything a big secret, and what … what does my brother have to do with any of it? And why the devil are you smiling that way, like a cat?”

“Because I am astonished, Mademoiselle, and not a little filled with admiration, that you have undertaken this little adventure with no knowledge whatever of its meaning.”

We had reached the ladder. I grabbed him by the arm and turned him around. “Then perhaps you might begin by explaining it to me.”

He shook his head and patted my cheek. His eyes were kind, and the smile had disappeared. “I cannot, of course. But when the patient is a little more recovered, it’s my professional opinion that you have every right to ask him yourself.”

5.

The next day, Stefan roared for his crutches, an excellent sign, but I wouldn’t let him have them. I made him eat two eggs for breakfast and a little more beef broth, and he grumbled and ate. I told him that if he were very good and rested quietly, I would let him try out the crutches tomorrow. He glared with his salt caramel eyes and directed me to go to the Isolde’s library and bring him some books. He wrote down their titles on a piece of paper.

The weather was hot again today, the sun like a blister in the fierce blue sky, and every porthole was open to the cooling breeze off the water. I passed along the silent corridor to the grand staircase, a sleek modern fusion of chrome and white marble, filled with seething Mediterranean light, and the library was exactly where Stefan said it should be: the other side of the main salon.

It was locked, but Stefan had given me the key. I opened the door expecting the usual half-stocked library of the yachting class: the shelves occupied by a few token volumes and a great many valuable objets of a maritime theme, the furniture arranged for style instead of a comfortable hours-long submersion between a pair of cloth covers.

But the Isolde’s library wasn’t like the rest of the ship. There was nothing sleek about it, nothing constructed out of shiny material. The walnut shelves wrapped around the walls, stuffed with books, newer ones and older ones, held in place by slim wooden rails in case of stormy seas. A sofa and a pair of armchairs dozed near the portholes, and a small walnut desk sat on the other side, next to a cabinet that briefly interrupted the flow of shelving. I thought, Now, here is a room I might like to live in.

I looked down at the paper in my hand. Goethe, Die Leiden des jungen Werthers; Locke, Some Thoughts Concerning Education; Dumas père, Le vicomte de Bragelonne, ou Dix ans plus tard.

When I returned to Stefan’s cabin a half hour later, he was sitting up against the pillows and staring at the porthole opposite, which was open to the breeze. The rooftops of the fort shifted in and out of the frame, nearly white in the sunshine. It was too hot for blankets, and he lay in his pajamas on the bed I had made expertly underneath him that morning, tight as a drum. “Here are your books,” I said.

“Thank you.”

“How are you feeling?”

“Like a bear in a cage.”

“You are certainly acting like a bear.”

He looked up from the books. “I’m sorry.”

“I’ve had worse patients. It’s good that you’re a bear. Better a bear than a sick little worm.”

“Poor Mademoiselle de Créouville. I understand your brother has ordered you to stay with me and nurse me back to health.”

“Not in so many words.” I paused. “Not in any words at all, really. He sent over a few clothes and a toothbrush yesterday, with the doctor, but there was no note of any kind. I still haven’t the faintest idea who you are, or what I’m doing here.”

He frowned. “Do you need one?”

I folded my arms and sank into the armchair next to the bed. His pajamas were fine silky cotton and striped in blue, and one lapel was still folded endearingly on the inside, as if belonging to a little boy who had dressed himself too hastily. The blueness brought out the bright caramel of his eyes and, by some elusive trick, made his chest seem even sturdier than before. His color had returned, pink and new; his hair was brushed; his thick jaw was smooth and smelled of shaving soap. You would hardly have known he was hurt, except for the bulky dressing that distended one blue-striped pajama leg. “What do you think?” I said.

He reached for the pack of cigarettes on the nightstand. “You are a nurse. You see before you an injured man. You have a cabin, a change of clothes, a dozen men to serve you. What more is necessary for an obedient young lady who knows it is impertinent to ask questions?”

I opened my mouth to say something indignant, and then I saw the expression on his face as he lit the cigarette between his lips with a sharp-edged gold lighter and tossed the lighter back on the nightstand. The end of the cigarette flared orange. I said, “You do realize you’re at my mercy, don’t you?”

“I have known that for some time, yes. Since you first walked into that miserable boathouse in your white dress and stained it with my blood.”

“Oh, you’re flirting again. Anyway, I returned the favor, didn’t I?”

“Yes. We are now bound at the most elemental level, aren’t we? I believe the ancients would say we have taken a sacred oath, and are bound together for eternity.” He reached for the ashtray and placed it on the bed, next to his leg, and his eyes danced.

“If that’s your strategy for conquering my virtue, you’ll have to try much harder.”

Stefan’s face turned more serious. He placed his hand with the cigarette on the topmost book, the Goethe, nearly covering it, and said, “What I mean by all that, of course, is thank you, Mademoiselle. Because there are really no proper words to describe my gratitude.”

I leaned forward and turned the lapel of his pajamas right side out. “Since we are now bound together for eternity,” I said, “you may call me Annabelle.”

6.

Of course, my full name was much longer.

I was christened Annabelle Marie-Elisabeth, Princesse de Créouville, a title bought for me by my mother, who married Prince Edouard de Créouville with her share of the colossal fortune left to her and her sister by their father, a New England industrialist. Textiles, I believe. I never met the man who was my grandfather. My father was impoverished, as European nobility generally was, and generously happy to make the necessary bargain.

At least my mother was beautiful. Not beautiful like a film star—on a woman with less money, her beauty would be labeled handsome—but striking enough to set her apart from most of the debutantes that year. So she married her prince, she gave birth to Charles nine months later and me another four years after that, and then, ooh la la, caught her husband in bed with Peggy Guggenheim and asked for a divorce. (But everybody’s doing it, my father protested, and my mother said, Adultery or Peggy Guggenheim? and my father replied, Both.) So that was the end of that, though in order to secure my father’s cooperation in the divorce (he was Catholic and so was the marriage) my mother had to leave behind what remained of her fortune. C’est la vie. We moved back to America and lived in a modest house in Brookline, Massachusetts, summering with relatives in Cape Cod, until Mummy’s appendix burst and it was back to France and Saint Cecilia’s on the storm-dashed Brittany coast.

“But that is medieval,” said Stefan, to whom I was relating this story a week later, on a pair of deck chairs overlooking a fascinating sunset. He was still in pajamas, smoking a cigarette and drinking a dry martini; I wore a lavender sundress and sipped lemonade.

“My father’s Paris apartment was hardly the place for an eleven-year-old girl,” I pointed out.

“True. And I suppose I have no right to complain, having reaped the benefit of your convent education. But I hate to think of my Annabelle being imprisoned in such a bitter climate, when she is so clearly meant for sunshine and freedom. And then to have lost such a mother at such an age, and your father so clearly unworthy of this gift with which he was entrusted. It enrages me. Are you sure you won’t have a drink?”

“I have a drink.”

“I mean a real one, Annabelle. A grown-up drink.”

“I don’t drink when I’m on duty.”

“Are you still on duty, then?” He crushed the spent cigarette into an ashtray and plucked the olive out of his martini. He handed it to me.

I popped the gin-soaked olive into my mouth. “Yes, very much.”

“I am sorry to hear that. I had hoped, by now, you were staying of your own accord. Do you not enjoy these long hours on the deck of my beautiful ship, when you read to me in your charming voice, and then I return the favor by teaching you German and telling you stories until the sun sets?”

“Of course I do. But until you’re wearing a dinner jacket instead of pajamas, and your crutches have been put away, you’re still my patient. And then you won’t need me anymore, so I’ll go back home.”

He finished the martini and reached for another cigarette. “Ah, Annabelle. You crush me. But you know already I have no need of a nurse. Dr. Duchamps told me so yesterday, when he removed the stitches.” He tapped his leg with his cigarette. “I am nearly healed.”

“He didn’t tell me that.”

“Perhaps he is a romantic fellow and wants you to stay right here with me, tending to my many needs.”

Suddenly I was tired of all the flirting, all the charming innuendo that meant nothing at all. I braced my hands on the arms of the deck chair and lifted myself away.

“Where are you going?” asked Stefan.

“To get some air.”

The air at the Isolde’s prow was no fresher than the air twenty feet away in the center of the deck—and we both knew it—but I spread my hands out anyway and drew in a deep and briny breath. The breeze was picking up with the setting of the sun. My dress wound softly around my legs. I wasn’t wearing shoes; shoes seemed pointless on the well-scrubbed deck of a yacht like this. The bow pointed west, toward the dying red sun, and to my left the water washed against the shore of the Île Saint-Honorat, a few hundred yards away.

I thought, It’s time to go, Annabelle. You’re falling in love.

Because how could you not fall in love with Stefan, when he was so handsome and dark-haired, so well read and well spoken and ridden with mysterious midnight bullets—the highwayman, and you the landlord’s dark-eyed daughter!—and you were nursing him back to health on a yacht moored off the southern coast of France? When you had spent so many long hours on the deck of his beautiful ship, in a perfect exchange of amity, while the sun glowed above you and then fell lazily away. And it was August, and you were nineteen and had never been kissed. This thing was inevitable, it was impossible that I shouldn’t fall in love with him.

For God’s sake, what had my brother been thinking? Did he imagine I still wore pigtails? I thought of the woman who had visited Stefan that first day, who had held Stefan’s hand in hers, tall and lithe and glittering. She hadn’t returned—women like her had little to do with sickrooms—but she would. How could you not return to a man like Stefan?

Time to go home, Annabelle. Wherever that was.

I closed my eyes to the last of the sun. When I turned around, Stefan’s deck chair was empty.

7.

I didn’t have much to pack, and when I finished it was time to bring Stefan his dinner, which I had formed the habit of doing myself. He wasn’t in his room, however. After several minutes of fruitless searching, I found him in the library, with his leg propped up on the sofa.

He waved to the desk. “You can put it there.”

“Oh, yes, my lord and master.” I set the tray down with a little more crash than necessary.

Stefan looked up. “What was that?”

I put my hands behind my back. “I’m leaving tomorrow morning. The wound is healing well, and you’re well out of danger of infection. You don’t need me.”

He placed his finger in the crease of the book and closed it. “What makes you think that?”

“Because the flesh has knit well, there’s no sign of redness or suppuration—”

“No, I mean thinking that I don’t need you.”

I screwed my hands together. “I’m going to miss this flirting of yours.”

“I am not flirting, Annabelle.”

His face was serious. A Stefan without a smile could look very severe indeed; there was a spare quality to all those bones and angles, a minimum of fuss. My hands were damp; I wiped them carefully on the back of my dress, so he wouldn’t see. “I’ve already packed,” I said. “It’s for the best.”

He went on looking at me in his steady way, as if he were waiting for me to change my mind. Or maybe not: Maybe he was eager for me to leave, so his mistress could return. Nurse out; mistress in. The patient’s progress. For everyone’s good health and serenity, really.

“Well,” I said. “Good night, then.”

“Good night, Mademoiselle de Créouville,” he said softly, and I turned and left the room before I could cry.

8.

I woke up suddenly at three o’clock in the morning and couldn’t go back to sleep. The wind had changed direction, drawing the yacht around on her mooring; you started to notice these things when you’d been living on a ship for a week and a half, the subtle tugs and pulls on the architecture around you, the various qualities of the air. My legs twitched restlessly. I rose from my bed and went out on deck.

The night was clear and dry and unnaturally warm. I had been right about the change in wind: the familiar shape of the Île Sainte-Marguerite now rose up to port, lit by a buoyant white moon. I made my way down the deck, and I had nearly reached the railing when I realized that Stefan’s deck chair was still out, and Stefan was in it.

I spun around, expecting his voice to reach me, some comment rich with entendre. But he lay still, overflowing the chair, and in the pale glow of the moon it seemed as if his eyes were closed. I thought, I should go back to my cabin right now.

But my cabin was hot and stuffy, and while it was hot outside, here in the still Mediterranean night, at least there was moving air. I stepped carefully to the rail, making as little noise as possible, and stared down at the inviting ripples of cool water, the narrow silver path of moonlight daring me toward the jagged shore of the island.

If I were still a girl on Cape Cod, I thought, I would take that dare. If I hadn’t spent seven years at a convent, learning to subdue myself, I would dive right off this ship and swim two hundred yards around the rocks and cliffs and the treacherous Pointe du Dragon to stagger ashore on the Île Sainte-Marguerite, where France’s most notorious prisoner spent a decade of his life, dreaming over the sea. I had been like that, once; I had taken dares. I had swum fearlessly into the surf. When had I evaporated into this sapless young lady, observing life, living wholly on the inside, waiting for everything to happen to me? When had I decided the risk wasn’t worth the effort?

I looked back over my shoulder, at Stefan’s quiet body. He wasn’t wearing his pajamas, I realized. He was wearing something else, a suit, a dinner jacket. As if he were waiting to meet someone, at three o’clock in the morning, on the deck of his yacht; as if he had a glamorous appointment of some kind, and the lady was late. The blood splintered down my veins, making me dizzy, the kind of drunkenness that comes from a succession of dry martinis swallowed too quickly.

You should wake him, I thought. You should do it. You have to be kissed by someone, sometime. Why not him? Why not here and now, in the moonlight, by somebody familiar with the practice of kissing?

“Good evening,” he said.

I nearly flipped over the railing, backward into the sea. “I didn’t realize you were here.”

“I’m here most nights. The cabin’s too stuffy for me.” He sat up and swung his left foot down to the deck, next to a silver bucket, glinting in the moonlight. “Join me. I have champagne.”

“At this hour?”

“Can you think of a better one?”

“I don’t drink on duty.”

“But you’re not on duty, are you? You have tendered your resignation to me, and rather coldly at that, considering what we have shared.” He rested his elbow on his left knee and considered me. I was wearing my nightgown and my dressing gown belted over it, like a Victorian maiden afraid of ravishment. My hair was loose and just touched my shoulders. “Is something the matter?” he said.

“No.”

“There must be something the matter. It’s not even dawn yet, and here you are, out on deck, looking as if you mean to do something dramatic.”

I laughed. “Do I? I can’t imagine what. I don’t do dramatic things.”

“Oh, no. You only wrap tourniquets around the legs of dying men—”

“You weren’t dying, not quite, and anyway, I wasn’t the one who put the tourniquet on you.”

He waved his hand. “You carry him in a boat across the sea—”

“Across a harbor, a very still and familiar harbor.”

“Toward an unknown destination, a yacht, and you nurse him back to health. All without knowing who he is, and why he’s there, and why he’s been shot through the leg and nearly killed. Whether you’ve just committed an illegal act and are now wanted by a dozen different branches of the police.”

“Am I?”

“I doubt it. Not in France, in any case.”

“Well, that’s a relief.”

He reached into his inside jacket pocket and drew out his cigarette case. “So I’ve been lying here, day after day, and wondering why. Why you would do such a thing.”

“You might just have asked me.”

“I was afraid of your answer.”

I watched him light the cigarette and replace the case and the lighter in his pocket. The smoke hovered in the still air. Stefan waved it away, observing me, waiting for me to reply.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of,” I said. “It’s simple. My brother asked me to.”

“You trust your brother like that?”

“Yes. He would never ask me to do something dishonorable.”

He muttered something in German and swung himself upright.

“You should use your crutches,” I said.

“I am sick of fucking crutches,” he said, and then, quickly, “I beg your pardon. I find I am out of sorts tonight.”

I gripped the rail as he limped toward me. “I suppose I am, too.”