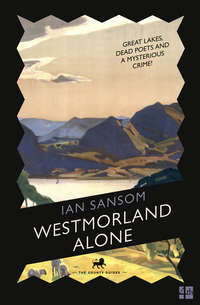

Westmorland Alone

It was indeed a marvellous diamond bracelet, as marvellous diamond bracelets go. Men had a terrible habit of showering Miriam with marvellous gifts – diamonds, sapphires, furs and pearls, the kind of gifts they wouldn’t dare to give their wives, for fear of raising suspicion.

‘Isn’t it more usual to exchange rings?’ I asked.

‘Oh, the ring is coming!’ said Miriam.

When the poor chap had finalised his divorce, I thought, but didn’t dare say.

The sound of the city was growing all around us: horse and carts, cars, charabancs, paperboys, and above it all, the sound of a woman nearby selling flowers. ‘Fresh flowers! Fresh flowers! Buy my fresh flowers! Flowers for the ladies!’

Miriam smiled her smile at me and glanced nonchalantly away.

‘Anyway, Sefton,’ she continued, ‘this means that I won’t be joining you and Father on any more trips. And so I just wanted some sort of guarantee that you’d be around for as long as this damned project takes. Father has become terribly fond of you, Sefton, as I’m sure you know.’

There was in fact very little sign of Morley’s having become very fond of me. Morley didn’t really do ‘fond’. I don’t think he’d have known the meaning of ‘fond’, outside a dictionary definition.

‘Sefton?’

I didn’t answer.

‘As you know, Father needs a certain amount of … looking after. After Mother died …’

Mrs Morley had died before I had started work with Morley; he and Miriam rarely spoke of her.

‘He needs a certain amount of care and attention. I hope you can—’

We were disturbed by the sounds of what seemed to be an argument – of an English voice uttering some low, strange, unfamiliar words, the sound of a woman shouting in response, either in distress or delight, of voices calling out, and of general confusion and hubbub.

‘Thank you!’ called the voice. ‘Gestena! Danke schön. Grazie. Go raibh maith agat! Xie xie. Muchas gracias!’ It was a Babel of thanks-giving. It could only be one person: Morley.

He approached us, be-tweeded, bow-tied and brogued as ever, and carrying what appeared to be every single British daily newspaper, and very possibly every European paper as well. He appeared indeed like an emblem or a symbol of himself: Morley was, basically, a machine for turning piles of paper into yet more piles of paper. He was also carrying, rather incongruously, an enormous bunch of gaudy and distinctly unfresh-looking flowers.

‘Ah, Sefton!’ he said, thrusting the flowers at me, and the newspapers at Miriam.

‘Flowers, Mr Morley?’

‘Oh no, sorry, they’re for Miriam. The papers are for us, Sefton, reading material on the way.’

I duly handed Miriam the flowers.

‘For me, really?’ she said. ‘You shouldn’t have, Sefton!’ She handed me the papers in return, shaking her diamond bracelet at me unnecessarily as she did so. ‘They’re lovely, Father, thank you.’

‘Well, I could hardly not buy any flowers from the woman, since she allowed me to practise my – admittedly rather rusty – Romani on her.’

I had no idea that Morley spoke Romani. But I wasn’t surprised.

‘Devilish sort of language. Do you know it at all, Sefton?’

‘I can’t say I do, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Dozens of varieties and dialects. Indo-Aryan, of course, but quite unique in many of its features – tense patterns and what have you. And only two genders. Easy to slip up. I fear I may have said something to upset the poor woman. I remember I was in Albania once and I thought I was complimenting this very proud Romani gentleman about his pigs, when in fact I said something about defecating on him and his family! Terribly embarrassing.’

‘Father,’ said Miriam. ‘That’s enough. Get in the car.’ This was one of Miriam’s more successful methods of dealing with Morley: shutting him up and ordering him around.

We were beginning to attract a small crowd of onlookers. The Lagonda was by no means inconspicuous, and Morley was the closest thing to a celebrity that one could possibly be without appearing on the silver screen. I scanned the crowd, beginning to feel distinctly uncomfortable. I half expected to see Delaney, Mickey Gleason, MacDonald, the police, or indeed my old varsity chums from the steps of Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court. Morley of course was unaware and oblivious, as always.

‘Anyway, Sefton, now you’re here you can tell me, what do you think of the Great North Road?’ He was shifting quickly and apparently senselessly from subject to subject – as was his habit.

‘The Great North Road, Mr Morley?’

‘Yes, indeed, the great English road, is it not? The spine of England! From which and to which everything is connected. Any thoughts at all at all at all?’

I had no thoughts about the Great North Road, and Morley wasn’t interested in my thoughts about the Great North Road. He was interested in using me as a sounding board.

‘Do you know Harper’s book on the road?’

‘I can’t say I do, Mr Morley, no.’

‘Pity. Marvellous book. Rather romantic and sentimental perhaps – and outdated, actually, thinking about it.’ His moustache twitched – the telltale sign of an idea forming. ‘Miriam, don’t you think we could perhaps produce our own little homage to the Great North Road on this trip? Four Hundred Miles of England?’

‘I think our hands are rather full at the moment, Father,’ said Miriam. She got out of the car, and ushered Morley into the back seat of the Lagonda, and began fitting his desk around him.

‘Well, a slim volume perhaps? Three Hundred and Forty Miles of England? We could stop our tour at Berwick-upon-Tweed?’

‘Yes, Father.’ This was another of Miriam’s techniques for dealing with Morley: humouring him. It seemed to work.

‘A little preface or prologue, perhaps? A record of significant stops and sights along the way. A kind of investigation of the meaning of the road. You know, I rather have the notion that it might be possible to invent an entirely new kind of writing about places – a kind of chronicling not only of their physical but also their psychical history, as it were.’

‘Psychical geography?’ I said.

‘Exactly!’ said Morley.

‘I don’t think it would catch on, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘No?’

‘No, Father.’

‘Well, just a straightforward guide then, perhaps? Stilton. Stamford. Boroughbridge. Are you a fan of Stilton, Sefton?’

‘Stilton, Mr Morley?’

‘The cheese, man. Are you a Stiltonite? Lovely with a slice of apple, Stilton.’

‘Where do you stand on Stilton, Sefton?’ asked Miriam.

‘The English Parmesan, Stilton,’ said Morley. ‘Or perhaps Parmesan is the Italian Stilton …’

‘Sorry?’

I was no longer listening. I had spotted a policeman who had noticed the crowd and who was now walking briskly towards us. He seemed to be looking directly at me. I was still standing by the Lagonda. I checked quickly behind me; if I was quick I’d be able to make it across the Euston Road and disappear.

All was not lost.

And then it was.

I had spotted him too late.

The policeman blew his whistle: many people had now stopped and were staring. I had nowhere to go.

‘Hey! You!’ he called, reaching the Lagonda. ‘You! What on earth are you doing?’

‘Excellent whistle!’ said Morley, from the back of the Lagonda.

‘What?’

‘Your whistle, Officer. I wonder, is it made by Messrs J. Egdon of Birmingham, by any chance?’

‘I have no idea,’ said the policeman.

‘They’re renowned for their whistles,’ said Morley.

‘Really? And you’re a whistle expert, are you?’

‘I wouldn’t say that …’ began Morley. He was a whistle expert, obviously.

‘Who are you and what do you think you’re doing?’ demanded the policeman.

‘Well, to answer your second question first, if I may,’ said Miriam. ‘I think you’ll find that what we’re currently doing is speaking with you.’

‘You are blocking the entrance to the station, madam,’ said the policeman, unamused.

It was true: Miriam had parked, as usual, without care or regard for other road-users, and our small gathering of onlookers had begun to cause a problem.

‘Oh, that!’ said Miriam. ‘Are we? Really? I hadn’t noticed. I’m terribly sorry.’

‘I’m not looking for an apology, madam. You realise I could book you under the Road Traffic Act of 1930 for obstructing the king’s highway?’

‘Oh, I’m sure you could book us, Officer,’ said Miriam, lowering her voice and fixing the poor policeman with her most glimmering smile. ‘But the question is, would you?’

This threw the policeman rather, who obviously was not accustomed to being flirted with by a woman of Miriam’s considerable expertise and world-class charms. He changed his line of questioning and turned to me.

‘Is this man with you, madam?’ He had clearly noted my rather rumpled appearance.

‘Him?’ said Miriam.

I could see that she was considering causing mischief. I prepared to sprint.

‘Of course!’ she said. ‘He’s my fiancé, aren’t you, darling!’ She leaned across the car and offered her cheek for me to kiss. I had no choice but to oblige. ‘He’s just bought me some flowers, Officer. Isn’t he adorable?’

‘Ha!’ came a laugh from the back seat.

‘And this gentleman?’ asked the policeman, nodding towards Morley.

‘This is my father, Officer.’

‘And where are you all headed this morning, might I ask?’ The policeman addressed his question to me.

‘We are headed to …’ I had no idea. Miriam and Morley usually didn’t tell me where our next destination was until we were en route. I rather suspected that this was often because they didn’t know themselves.

‘We are headed, sir, to the very heart of the country!’ said Morley. ‘The hub! The centre! The cultural capital!’

‘And where is that exactly?’ asked the policeman, having extracted a notebook from his pocket and taken down the registration of the car.

‘Westmorlandia!’ said Morley. ‘Westmoria! The western Moorish county.’ He began whistling the Toreador Song from Carmen. (He had a recording of the Spanish mezzo-soprano Conchita Supervia singing the role of Carmen, which he claimed was one of the great cultural achievements of all time. He also claimed this, it should be said, for Caruso singing ‘Bella figlia dell’ amore’ in Rigoletto, Rosa Ponselle in Tosca, and John McCormack singing just about anything.)

‘No. Still no wiser, sir. If you wouldn’t mind spelling that for me?’

‘Westmorlandia! One of the truly great English counties!’ continued Morley. ‘Home of the poets! Land of the great artists! We shall be visiting the mighty Kendal. Penrith – deep red Penrith! Ambleside. And we shall follow the River Eden as she rises at Mallerstang and makes her majestic way to the Solway Firth—’

‘We’re visiting the Lake District, basically,’ said Miriam.

‘Ah,’ said the policeman, writing in his notebook.

‘Westmorland!’ cried Morley. ‘Do get it right, Miriam, please. Westmorland! Which – combined with Cumberland – might together accurately be described as “the Lake District”, though of course the designation is rather misleading because—’

‘And what is your business exactly in Westmorland, sir?’

‘Our business? Our business, sir, is to do no less than justice and no more than to offer honest praise!’

‘Exactly what is your business in Westmorland, sir?’ The policeman was getting tired: I’d seen it before. Morley’s eccentricities could be extremely wearing.

‘We are writing a guidebook,’ said Miriam. ‘To the county and its—’

‘Roofs!’ cried Morley. ‘The roofs of Westmorland are some of the finest in the land, Officer. Did you know?’ Morley had a great enthusiasm for roofs. He began explaining the quality of the roofs of Westmorland to the policeman, who wisely decided at that point that it was time to give up.

‘On you go then, please,’ he said. ‘If you don’t mind. Move along now, people,’ he told the crowd. ‘There’s nothing to see here.’

‘Thank you, Officer,’ said Miriam. ‘Come on, darling,’ she said to me.

I remained silent and did not breathe a sigh of relief until the policeman had plodded his way far enough from the car and the crowd had begun to disperse, and then I breathed a very big sigh of relief indeed.

‘Let’s go,’ I said to Miriam, moving quickly around to the passenger side of the Lagonda.

‘All aboard the Skylark!’ cried Morley.

‘You’re keen all of a sudden,’ said Miriam to me.

‘Charming man,’ said Morley. ‘The British bobby – curious, steadfast, and yet always polite.’

‘Indeed,’ said Miriam. ‘Now, gentlemen, shall we just check our route.’ She produced a map and several of the boards onto which Morley had mounted his county maps. ‘Our route. We begin in London, obviously.’

‘Starting at the GPO?’ said Morley. ‘The traditional starting point of the Great North Road?’

‘Starting here, Father. And then Herts, and Beds, and Cambridgeshire, Rutland, Lincs, Notts, West Riding—’

‘And then a left turn at Scotch Corner?’ said Morley.

‘And then a left turn at Scotch Corner,’ agreed Miriam.

I was half listening and had already begun opening the door when I saw him: MacDonald. He was perhaps a hundred yards away, across the other side of the Euston Road. I recalled him mentioning before that he lived somewhere up around King’s Cross. When he saw me, as inevitably he would, he would doubtless want to raise the small matter with me of my having abandoned our card game, and possibly the no less small matter of my having departed with several packets of Delaney’s precious ‘snuff’.

I stood rooted to the spot.

‘Scotch Corner,’ continued Morley, ‘being of course the junction of the traditional Brigantian trade routes in pre-Roman Britain, and the site where the Romans fought the Brigantes. The Brigantes being?’

‘A Northern Celtic tribe, Father,’ said Miriam wearily.

‘Correct! And they fought the Romans at the Battle of?’

‘Scotch Corner?’ I said.

MacDonald had seen me. He stared for a moment in surprise and then smiled a dark smile and began making his way hurriedly through the traffic. I had less than two minutes. If I stayed with Miriam and Morley and the car we wouldn’t be going anywhere fast.

I had a choice. I could either make a run for it or …

‘The Battle of Scotch Corner is correct!’ said Morley. ‘You know, perhaps you’re finally getting to grips with this stuff, Sefton. We’ll also have a look at the Stanwick fortifications, which are about five miles north-west of Scotch Corner, and which I think I’m right in saying form the most extensive Celtic site in Britain—’

‘I think I might get the train, actually, Mr Morley, and meet you there.’

‘The train?’ said Miriam.

‘Ah!’ said Morley. ‘You’re thinking of the Settle–Carlisle line, Sefton, are you not? Possibly the greatest railway line in the country. A sort of railway companion to our Great North Road journey?’

‘Exactly,’ I said. ‘That’s exactly what I’m thinking, Mr Morley.’ MacDonald was twenty yards away and closing fast. ‘I would just need some money, to—’

‘Of course,’ said Morley. ‘Good thinking, Sefton. I think it would certainly add immeasurably to the book if you were to travel by train, we were to travel by car, and then we could compare notes when we arrive in Westmorland and—’

‘I really need to go now though.’

Morley consulted his two watches – the luminous and the non-luminous dials.

‘Yes, the seven fifteen, would that be it?’ He had – naturally – memorised most of Bradshaw’s. ‘If you hurry you might just catch it.’

‘I’m going to catch it.’

‘Good, now let’s give the man the means, Miriam, shall we?’

Miriam looked at me suspiciously but nonetheless began rooting around in her handbag.

‘And the camera, Miriam, give him the camera. Come on, hurry!’

‘The new Leica, Father? But I thought I might—’

‘Now, now, Sefton is our photographer. We did buy the camera for him. It’s the new Leica, Sefton. I was particularly impressed by the set-up we saw in Devon, and I thought perhaps you might enjoy using it. Give you something to play with on the train.’

‘I’m sure Sefton will find something to play with on the train,’ said Miriam, handing over the camera and a handful of cash. ‘That should be enough to cover a third-class fare, Sefton. You’ll be travelling third class, of course?’ Miriam smiled at me.

‘For colour?’ said Morley. ‘Yes, good thinking, Miriam. Travelling with the people. Ours is a people’s history, after all.’

‘Of course,’ I said.

MacDonald was just five yards away. I could see the veins throbbing in his neck and his eyes bulging.

‘I think we’ll beat you to it,’ said Miriam, but I didn’t answer: I had already begun to run.

‘Sefton!’ shouted Miriam after me. ‘Where will we see you?’

‘Appleby!’ cried Morley. ‘The county town of Westmorland! We’ll meet you at Appleby, Sefton!’

I ran into the station, shouting to the porters for the seven fifteen: they pointed me to platform 3. I ran past the ticket inspector and made it to the last carriage of the train, where a young mother was struggling to get on with a young girl and a baby. The guard was calling the departure as I managed to lift up the girl and slam the door behind us – and the train shuddered forward.

I stood for a long time at the window looking out for MacDonald, but there was no sign of him. I must have lost him in the crowd.

Satisfied, I made my way to a compartment, squeezing past fellow passengers and their luggage. There was the woman with the baby and the child.

‘Mummy, Mummy,’ said the little girl. ‘It’s the nice man, Mummy.’

The young woman smiled at me warmly.

‘Do you mind if I join you?’ I said.

‘Of course,’ she said. ‘Thank you so much for helping.’

‘The baby will cry,’ said the little girl. ‘But all babies cry. What’s that?’ she asked, pointing at the Leica.

‘It’s a camera,’ I said.

‘What’s a camera?’

‘It’s something that you can take pictures with.’

‘Like a drawing?’

‘Yes, I suppose.’

‘Is there a pencil inside it?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘There’s not a pencil.’

‘Is there a pen?’

‘No, there’s not a pen either.’

‘Is there paint?’

‘Look,’ I said. ‘Do you want to see?’

The girl looked at her mother, her mother nodded, and the little girl came and sat close to me; as we left London I showed her how to open the camera, how to check the shutter and the focus and how to frame a photograph. I took her photograph and she took mine.

‘Are you coming with us?’ asked the girl. ‘Mummy, can the man come with us?’

‘The man is on his own journey,’ said the mother. ‘He’ll be going somewhere himself.’

‘We’re going to Carlisle,’ said the little girl. ‘Where are you going?’

I looked at her. I felt suddenly exhausted. ‘I don’t know, actually,’ I said. ‘I don’t know where I’m going.’

‘You’re funny,’ said the girl. ‘You’re a funny man!’

‘He’s just tired,’ said the mother. ‘Let him rest now.’

CHAPTER 3

72 MILES, 1,728 YARDS

IT WOULD NOT BE an exaggeration to say that Morley was obsessed with the Settle–Carlisle line. He was obsessed with a lot of things, of course, but the Settle–Carlisle remained for him one of the great foundation stones – ‘one of the canonical lines’, he famously called it – of England. I have no doubt that if he could have seen the destruction later wrought upon the railways he would not have despaired: he simply would not have let it happen. There would have been campaigns, organisations, books, leaflets, marches on London, a popular uprising: Mr Beeching would have taken one hell of a beating.

After our trip to Westmorland, Morley revised and updated his famous book, 72 Miles, 1,728 Yards (1935), in which he describes the route of the Settle–Carlisle line, mile by mile, yard by yard, tunnel by tunnel, viaduct by viaduct, every gradient, every ascent, every twist and every turn. I doubted that the new edition would sell a single copy. It became a bestseller. His most popular lecture series – by far – during our time together was on the Settle–Carlisle line, more popular than the ‘World of Wonders’ series and the ‘Home Husbandry’ series combined, more popular even than the infamous ‘Communism, Fascism: What Exactly is the Difference?’ lecture, which always drew a crowd (and which, indeed, on a number of occasions, caused a riot). In the Settle–Carlisle lectures he lovingly described the planning and construction of the line, its maintenance, and its day-to-day operations, beginning and ending with a sing-song recitation of the names of all the stations: Settle, Horton-in-Ribblesdale, Ribblehead, Dent, Garsdale, Kirkby Stephen, Crosby Garrett, Ormside, Appleby, Long Marton, Newbiggin, Culgaith, Langwathby, Little Salkeld, Lazonby and Kirkoswald, Armathwaite, Cotehill, Cumwhinton, Scotby, Carlisle. Anywhere north of Watford the recitation of the station names alone would often earn him a standing ovation. (Admittedly, the lectures tended to be less popular in the Home Counties, though they played surprisingly well in London.)

Indeed, in recognition of his work promoting the railway industry in general and the Settle–Carlisle line in particular the big four railway companies – the old LNER, and the GWR, the LMS and SR – awarded Morley in 1939 a fat little golden locket, inscribed with his name, on a chain. He needed only present the locket to a ticket inspector on board a train to be granted free first-class travel the length and breadth of the country. Morley cared almost nothing for awards and baubles: one bathroom at St George’s was rather eccentrically papered with moulding black and white certificates and citations that might more usually have been proudly framed and displayed, and a crusty old armoire in a guest bedroom served as storage space for his various medals, statuettes and gifts ‘in recognition of’, many of them featuring depictions of pens and quills carved in marble, onyx, or, in one case – after our trip to Durham – made out of coal. Morley referred habitually to such awards and honours as ‘chaff’ and, occasionally, as his ‘pointless paper empire’.* But the Big Four locket travelled with him everywhere until the day he died.

According to Morley in 72 Miles the Ribblehead viaduct was one of the modern wonders of the world, and the route of the Settle–Carlisle line ‘a journey into the heart of England and Englishness’. (He also made this claim, it should perhaps be conceded, about the west Norfolk coastal route, the GWR journey down to Devon, the Esk Valley line, and the all-electric Southern Belle route from Victoria to Brighton.) Describing the Settle–Carlisle line he rose to sweeping rhetorical heights:

There is perhaps not even in Switzerland, nor in India, nor indeed in our own green and pleasant land, a more magnificent journey than that through the great valley of the Ribble, and on round the broad shoulder of the mighty Whernside at Blea Moor, on through the valleys of the Dee and Garsdale, up and over the watershed to the summit at Aisgill, and then through the justly named Eden Valley towards Carlisle. If the good Lord Himself had been a railway engineer during the glory years of the mid- to late nineteenth century, he could not have plotted a finer route.

‘The Settle–Carlisle line is not a journey by rail,’ he famously concludes 72 Miles. ‘It is the journey of a soul.’ There was perhaps a slight tendency in all his work for Morley to wax unnecessarily lyrical but in his great paean to the Settle–Carlisle line his prose found its proper subject. The book combined perfectly his poetic instincts with his obsessive practical concerns. He was an expert on every aspect of the line, from the ‘long, tall’ Douglas fir and Baltic pine sleepers, to the ‘doughty’ granite chipping ballast, the ‘proud’ stations, the tunnels, the viaducts and the signals. And of course, alas, he became an expert on its tragedies.