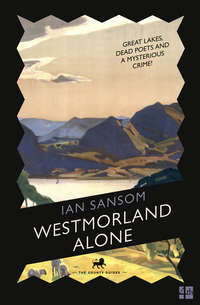

Westmorland Alone

‘I’ve not seen it like this since t’fair,’ said one woman, as I jostled my way past.

‘Folk turning out to gawk,’ said another. ‘T’ should be ashamed.’

People were not ashamed, but they were baffled, just as we were baffled. ‘What happened?’ came the endless murmur. ‘What happened?’

Lucy’s mother with her baby walked on up ahead of me, weeping. I made no attempt to go to her, to comfort her or to apologise: I simply lowered my head and walked on.

In Spain I had often suffered exactly the feeling of that afternoon in Appleby: of arriving in a strange town, and not quite knowing or understanding what was happening, and with the knowledge and feeling of already having done something terribly wrong, so that the whole place seemed alien and unkind, a foreign land inhabited by foreign people suffering their uniquely foreign woes in their uniquely foreign ways. According to Morley in the County Guides, Appleby is renowned for its beautiful main street, ‘more Parisian boulevard than English High Street’ but I must admit that on that first day I did not much notice its beauty, and which particular Parisian boulevard Morley had in mind is not entirely clear, since there are none, to my knowledge, that are furnished with butchers, bakers, chandlers, haberdashers, gentlemen’s outfitters, greengrocers and pubs; Paris, for all its allurements, is no real comparison for a prim and proper English county town. A finer and – as it turns out – more fitting comparison for Appleby might be with a Wild West frontier town, in florid English red stone.

The Tufton Arms Hotel had seen better days, though it was difficult to say exactly when those days had been. It was a sad sort of place: scuffed, worn moquette carpets, cheap and pointless marquetry, cracked clerestory lights, plush, dusty furniture; like a vast dull first-class carriage. The hotel bar was the centre of operations. Tea urns had been set out on some of the tables, and plates of bakery buns. There was much bustling and much organising being done: volunteers from the local Band of Hope had somehow appeared, with their own banner, and had positioned themselves in the hotel lobby, arranging places for people to stay, and drawing up lists and matching locals with passengers; the Women’s Institute were doling out the tea and buns; and the police had settled themselves in to conduct interviews. Morley later wrote in praise of the scene as a ‘model of modest English efficiency’. It may have been. It may have been a demonstration of all that is best in the human spirit, a triumph of calm over distress and of civilisation over human wretchedness. All I know is that it was thoroughly depressing and that I was desperate to get away. I needed a drink.

‘Yes, sir?’ asked the barman – one of those old-style hotel barmen, a professional barman, a middle-aged gent, spruce and natty, in a tight little tie and a bottle-green waistcoat. He might just as easily be a town councillor or a greengrocer.

‘Whisky, please.’

‘So, were you in the crash?’ he asked. My torn jacket and bloodied shirt, the bump on my head, and the ragged trousers must have been a give-away. I didn’t answer. ‘Very good, sir. Drinks are on the house for anyone who was in the crash.’

‘In that case make it a double,’ I said.

‘There’ll be no trains in or out for a week, I reckon,’ continued the barman, as he was examining the bottles behind the bar. ‘So I reckon we’ll be getting through a lot of port and lemon.’ He nodded towards the crowd around the bar, mostly women. ‘So, Scotch: we’ve got Haig, Black and White, or Macnish’s Doctor’s Special. Irish, I’m afraid we’ve only Bushmills or …’ He held up a full bottle of Irish whiskey. ‘Bushmills.’

‘I’ll take a Bushmills then.’ I had converted to Bushmills at one of Delaney’s places: he served only Irish whiskey, his famous gin fizz, and other drinks even more distinctly suspect and of no discernible provenance.

‘There was a little girl killed,’ he said. ‘Is that right?’

I said nothing. I drank the whiskey and ordered another. And then another.

I could see her face in the mirror behind the bar. I could see her smile. I could feel her hand holding mine. I could hear her asking questions. She seemed to be everywhere. But the more I drank the quieter she became. I also took a pinch or two of Delaney’s powders – and eventually she was silent.

Morley, hectic and inquisitive as ever, had conveniently situated himself at the far end of the table at which the police had made their makeshift headquarters – the perfect location for a quiet spot of eavesdropping. He was armed with a cup of black tea, and was busy with his pen writing in one of his tiny German waistcoat-pocket-sized notebooks. He had about him his usual glow. Miriam was smoking and surveying the room with a look of pity and disgust. I sat down with them. I felt sick.

‘Ah, Sefton,’ said Morley. ‘The hero of the hour.’

‘Hardly,’ I said.

‘Come, come, we’ve heard all about your exploits, dragging people from their carriages and what have you, saving lives—’

I got up to leave, but Miriam gripped my arm and forced me to sit back down.

‘He’s had a shock, Father. Best to leave it.’

‘Of course!’ said Morley. ‘Yes, of course, quite upsetting.’

‘I wonder actually if, in the circumstances, we should perhaps call a halt to the book, Father,’ said Miriam.

‘Agreed,’ I said.

‘Yes,’ said Morley, to my surprise. ‘Perhaps we should.’

‘Really?’ said Miriam.

‘Till tomorrow morning, perhaps?’

‘What?’ I said.

‘Otherwise we would slip very far behind in our schedule, Miriam.’

‘Our schedule,’ I said, with contempt.

‘Is something wrong, Sefton?’ asked Morley.

‘Father,’ said Miriam, coming to my rescue. ‘I was thinking we should perhaps take a longer break?’

‘Agreed. Again,’ I said.

‘A longer break?’ In all my years with Morley I rarely saw him riled or succumbing to petty rages, but this suggestion made him spiteful. ‘Do you both want us to give up then?’ said Morley. ‘Just because there’s been a train crash?’

‘No,’ said Miriam slowly, as if speaking to an ignorant child. ‘But you’re right: there has been a train crash.’

‘And what on earth do you propose doing when real disaster occurs?’ asked Morley. ‘As it surely will.’

‘Real disaster?’ I said.

‘A war, or a famine? Another Spanish flu? A crash is an accident. It may be a tragedy. But it is not, strictly speaking, a disaster. Do you know what a disaster is?’

‘I think I do,’ I said.

‘Has there been great loss of life?’

‘A little girl died, Father!’ said Miriam.

‘Which is tragic, but as I say, it is not—’

I moved to get up again and again Miriam held me back.

‘I’m sorry but I have no intention of continuing to work with you on this book at this time, Mr Morley,’ I said.

‘And I have no intention of allowing you to give up our enterprise at this time, Sefton, simply because of misfortune. Would any great art ever have been created if we had given up because of some setback? Did any of us give up what we were doing during the Great War? Did I give up when my son and my wife—’

‘And did I give up when in Spain—’

‘Boys! Please!’ said Miriam, slapping the table with both hands. ‘I have no intention of allowing you two to bicker like children. Of course Sefton won’t be giving up on the project, will you, Sefton?’ She glared fiercely at me.

‘Well, it rather sounds like it to me,’ said Morley. ‘Tu ne cèdes.’

‘We are not talking about giving up, Father. But I do think we might at least pause in our endeavours until the tragic matters here are in some way resolved.’

Morley huffed. I gazed distractedly around the room.

‘You know you can be terribly insensitive sometimes,’ said Miriam.

‘Insensitive?’ cried Morley. ‘Me? Insensitive?’

Fortunately – before I walked off, or struck Morley for his self-righteous stupidity – our conversation was interrupted by a young man who had sidled over, obviously intent on talking to us. He looked as though he might be a butcher’s boy: his face was flushed, and he had that soft, odd, awkward manner of someone more at home with animals than with humans. He was not in fact though a butcher’s boy: he was a reporter from the Westmorland Gazette. (Morley, who had of course started out as a muck-raking journalist, had little time for practitioners of his previous profession. In private he referred to them unflatteringly as ‘Gobbos’, after Shakespeare’s word-mangling idiot in The Merchant of Venice. In Morley’s Defence of the Realm (1939) he describes journalists as ‘allowed fools, paid to express contempt for people, politics, religion and society as a whole’. Over the years he described journalists variously to me as ‘vampires’, ‘grave-robbers’, ‘cutpurses’, but also as ‘the just’, as ‘valiant heroes’, and as ‘seekers after the truth’. His feelings and ideas were often inconsistent and contradictory.)

‘The Westmorland Gazette!’ cried Morley. ‘Of course! Thomas De Quincey’s old paper, is it not?’

‘I believe so, sir, yes.’

‘Founded when?’

‘I’m not entirely sure, sir.’ The young chap’s red-flushed cheeks flushed all the redder.

‘Don’t know when? You write for the newspaper and you don’t know when it was founded?’

‘No, sir.’ The poor fellow had round, pleading eyes.

‘Do you know the date of your mother’s birthday?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And your father’s?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘I rest my case,’ said Morley, though exactly which case he was resting I was not entirely sure. His metaphors and analogies were not always entirely clear or helpful. ‘I think you’ll find it was established in 1818.’

‘Sorry, sir.’

‘“Sorry, sir”?’ cried Morley, almost knocking over his cup of tea. ‘“Sorry, sir”? A little more gumption wouldn’t go amiss, young man. I’m not at all sure you’re cut out for this business. Well, do you have any questions for us?’

The young man began frantically flicking through his notebook.

‘Wordsworth one of the original backers, I think?’ said Morley. ‘Was he not?’

‘Of?’

‘The paper, man!’

‘I’m not sure, sir—’

‘Everybody knows it was Wordsworth! Late Wordsworth. Reactionary Wordsworth. Prefer the young Wordsworth myself, but never mind. And De Quincey was the first editor, I believe – or the second? – though he was so drugged with his laudanum that he refused to go to the office. Still the case with your current editor?’

‘Not as far as I’m aware, sir, no.’

‘And does the paper still take the Tory line?’

‘I’m not sure, sir.’

‘You’re not sure?’

‘I’ve only just started work at the paper, sir.’

‘Well, you’ll not be working there long at this rate, will you, man? Original motto of the paper?’

‘Erm …’

‘“Truth we pursue, and court Decorum: What more would readers have before ’em?” Rather good, isn’t it?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘And do you pursue Truth and court Decorum, young man?’

‘I suppose I do, sir.’

‘Well, that’s a start, I suppose,’ said Morley. ‘Offices where, in Kendal?’

‘Yes, sir. On Stricklandgate.’

’You are a lucky young fellow. Probably the finest patch for a newspaper man in the whole of England, the Westmorland Gazette. From the hill farms of the Yorkshire Dales in the east to Furness in the west, and Helvellyn in the north to Morecambe Bay in the south …’

‘I suppose so, sir, yes.’

‘You suppose? You suppose? Well then, ask another question, man!’ Morley produced a pocket egg-timer and placed it on the table. ‘You’ve got three minutes.’

‘I just wondered if you’d give me a quote, sir, about the rail crash, and your role in—’

‘Give you a quote? One doesn’t give quotes, young man. People speak, and one shapes their words, like a mother bear licking a cub into shape.’

‘Well, if you wouldn’t mind—’

‘I am reminded of the words of the great Dean Swift, sir: “For life is a tragedy, wherein we sit as spectators awhile, and then act our part in it.”’

‘Is that a quote?’

‘It’s a quote of a quote.’

‘Ah.’

‘Just write it down,’ said Miriam. ‘It’ll do.’

‘I’m afraid I cannot comment on the accident until the police have conducted their investigation and compiled their accident report,’ added Morley. ‘Next question?’

‘Is it true that the train was speeding, and that—’

‘I refer you to my previous answer. Next question!’

‘Is it true that you rescued a number of people from the carriages?’

‘I can make no such claim. The person who did so is my assistant, Stephen Sefton, who is— Sefton?’

I had made myself scarce, slipping away from the table and behind Morley to the bar. I had absolutely no desire to hear him engage in Socratic dialogue with some poor young reporter from the Westmorland Gazette, and even less desire to appear in the Westmorland Gazette.

‘Sefton?’ called Morley across the packed room. I was only a few yards away, but the crowd was dense. ‘Sefton?’ I made no response. ‘He’s probably gone to get another drink. Do you indulge?’ he asked the boy reporter.

‘Indulge?’

‘In drink?’ said Morley.

‘Well, I have occasionally—’

‘Don’t,’ said Morley. ‘The best advice I can give anyone is the same advice my father gave me as a young man: don’t smoke, drink or fornicate, and never bring the police to the door.’

Such advice was too late for me, alas: I was already busy with another Bushmills and was immersing myself in the day’s Times, looking for news of the police searching for a man following an assault outside Marlborough Street Magistrates’ Court. There was nothing that I could find. I sank the whiskey.

‘Three minutes!’ I heard Morley announce, snatching up his egg-timer. ‘That’s your lot, boy. You’re really going to have to work on that interview technique.’

The poor boy reporter got up and left, and I returned safely to the table.

While all this was going on the policemen at the other end of our table were conducting interviews with passengers: I knew that sooner or later they were going to want to interview me. I was dreading the moment. I had too much to say to them without making any admissions or speaking any untruths. They were a typically unlikely and unprepossessing bunch of country coppers: one of them had big ears like wingnuts, almost like a character in a children’s comic; another was broad and squat, almost square, and was busy writing everything down, though it looked rather as though he was unaccustomed to handling a pen; and the third, clearly the most senior officer, had a bald head and a bottle-brush moustache, and he kept scratching at his rather scraggy neck and rubbing a hand across his brow, as though trying to soothe his troubled mind. Passengers were ushered before this trio by a formidable woman in a shop coat called Mrs Sweeton who seemed to have appointed herself as official usher. ‘Thank you, Mrs Sweeton,’ the senior policeman would regularly pronounce. ‘Next, Mrs Sweeton.’ I rather fancied that they knew each other very well. The passengers gave their statements and then were ushered away again. ‘Thank you, Mrs Sweeton. Thank you, Mrs Sweeton.’

Morley was clearly keeping a keen and close eye on all this, and as I sat back down at the table he shushed me and indicated to me with his hand that I should sit and be quiet, attend to the conversations, and take notes. Another man was being ushered before the police – but this was no passenger.

The crowd in the bar parted as he was escorted to the table by two gentlemen dressed in LMS uniforms, like captains of the guard – thick black blazers, emblazoned caps and shiny brass buttons. I had seen the man they were escorting at the scene of the crash, frantically rushing first to the front of the train and then back to the rear. He was tall and good-looking, with high cheekbones, and though smartly turned out in his own LMS uniform he looked terribly afraid and uncertain.

‘He’s dishy,’ said Miriam to me, as he sat down at the table: he was the sort of young man, I thought, who might easily attract the wrong sort of woman.

A total hush fell over the thronging crowd.

It was George Wilson, the Appleby signalman.

CHAPTER 6

THE LOCOMOTIVE ACCIDENT EXAMINATION GUIDE

THOUGH WE WERE SITTING NEARBY, close enough to hear, it wasn’t possible to pick up every word of the police interview over the hubbub of the bar – after a few preliminary questions the crowd had returned to their own rumours and conversations – and it wasn’t until the senior policeman raised his voice that the conversation with the signalman became entirely clear.

‘So, can you think of any reason for the engine derailment?’

‘Axle defect, bearing failure, boiler defect, bolt failure, brake failure, broken rail, debris, defective this or that, drive shaft failure, driver error, fireman error, excessive loading, excessive speed, lack of signal detection, landslip, signal layout defect. Series implexa causaram.’ This was not, suffice it to say, the signalman’s answer. It was Morley, interrupting.

‘I beg your pardon?’ said the policeman, looking across for the first time at the three of us perched at the end of the table. ‘I don’t think you’re a part of this conversation, sir, are you?’

‘And signalman error,’ said Morley, to the signalman. ‘If you don’t mind my saying so. Let’s not assume. It’s a checklist, from The Locomotive Accident Examination Guide, I think, first published by Hoyten and Cole in—’

The policeman looked despairingly at his two companions.

‘I do mind you saying so, sir, actually. And I’d be grateful if you’d keep your thoughts to yourself for the moment. If you were involved in the crash you’ll have an opportunity to give a statement, along with everyone else.’

‘Father,’ said Miriam, with a voice of restraint. ‘Irritabis crabrones.’

‘It’s only what the company’s accident expert will say, when he arrives,’ said Morley. ‘I thought it might save you some time.’

‘He’s only trying to help,’ said Miriam. ‘Sorry, Officer.’

‘Si cum hac exceptione detur sapientia, ut illam inclusam teneam nec enuntiem, reiciam.’

‘What’s he saying?’ asked the policeman.

‘If wisdom were offered me on condition that I should keep it bottled up, I would not accept it,’ said Miriam. ‘Roughly.’

‘Well, he’s going to need to bottle it up for the moment, if you don’t mind. We’re more than qualified to be able to get to the bottom of things, thank you. We’re just trying to establish what might have happened—’

‘I know what happened,’ said the signalman.

‘What?’ asked Morley.

‘Please!’ said the policeman. ‘I’m conducting an interview here.’

‘Apologies, Officer,’ said Morley.

‘What happened, then?’ the policeman asked the signalman.

‘I was about to say,’ said the signalman. ‘I’ve already explained to Eric—’

‘The stationmaster?’

Eric, standing smartly by the table, quietly nodded, his LMS cap lending the nod an air of locomotive authority.

‘Well?’ said the policeman.

‘It was children on the line. I didn’t have any choice.’

‘Children?’ said the policeman.

‘Gypsy children. It’s those ones that come for the fair, and then never went away,’ said the signalman.

‘The Appleby Fair,’ said Morley to me.

I wrote it down.

‘The Appleby Fair,’ said the policeman.

‘That’s right,’ said the signalman. ‘They come up here and then they hang around and you can’t get rid of the buggers and they let their bloody children run wild, and if it wasn’t for them—’

‘You know, I have always wanted to visit the Appleby Fair,’ said Morley to me.

‘You’re not missing anything,’ said the signalman to Morley. ‘And if it wasn’t for those bloody kids none of this would have happened. I didn’t have any choice. I had to divert the train into the dairy siding.’

‘The dairy siding?’ asked Morley.

‘The Express Dairy Creamery. The milk goes down to London.’

‘I see,’ said the policeman. He sat back in his chair and sighed.

There was an awkward silence. The police looked relieved. The stationmaster, his companion and the signalman looked devastated: this was their crash, after all. Morley, unfortunately, was determined to make it his.

‘An interesting case, is it not?’ said Morley.

‘If you wouldn’t mind leaving the police work to us, sir,’ said the policeman.

‘Philosophically interesting, I mean, Officer.’

‘Sorry, sir, you are?’ asked the policeman.

‘Swanton Morley,’ announced Morley, in his brisk, no-nonsense fashion.

‘The People’s Professor?’ said the policeman.

‘I am sometimes referred to as such, yes,’ said Morley.

The policeman’s manner changed entirely. ‘Very nice to meet you, Mr Morley.’ He leaned across the table and vigorously shook Morley’s hand. ‘My father was a great one for your books, sir.’

‘I’m delighted to hear it.’

‘He loved your books on wildlife,’ continued the policeman.

‘Very good,’ said Morley.

‘And the ones on hobbies and home improvements.’

‘Excellent.’

‘He was less keen on the philosophical ones.’

‘Ah, well—’

‘And I’ve never read any myself. We gave them all away when my father passed on.’

‘Well, never mind,’ said Morley. ‘What we have here, funnily enough, is a classic philosophical problem.’

‘Is it indeed?’

‘It is. A classic moral dilemma.’

‘You’d better write that down,’ the senior policeman instructed his burly colleague.

‘Really, Sergeant?’ asked the burly one.

‘Write it down,’ repeated the policeman. ‘It might be significant.’ He stared at Morley as if beholding a work of art. ‘The People’s Professor, well, well. Lads, you’ve read the People’s Professor?’ The two other policemen shook their heads.

‘Ah well,’ said Morley to me. ‘Non quivis suavia comedit edulia.’

‘What did he say?’ the policeman asked Miriam.

‘Not sure,’ she said.

‘Marvellous,’ said the policeman.

‘Notebook to hand?’ Morley asked me. This usually meant that he had seen some opportunity and was about to deliver an impromptu lecture, which he wished to be recorded for posterity. An opportunity this clearly was. I did not alas have a notebook to hand. These are merely my recollections.

‘Might I elaborate?’ he asked the policeman.

‘By all means, Mr Morley.’

Morley turned to address the signalman, who was looking defeated and ashamed. ‘I’m so sorry you should have been faced with such a dilemma, young man. Mr Wilson, is it not, if I heard correctly?’

‘That’s right, sir. George Wilson.’

‘Well, Mr Wilson, I’m afraid you have been confronted with one of the fundamental questions in ethics.’

‘Has he?’ said the policeman.

‘Indeed he has. We might call it the “Changing the Points Problem”.’ (For a full elaboration of the problem, see Morley’s article, ‘The “Changing the Points Problem”’ in the Journal of Philosophy, vol.113, summer 1938: another article that caused more trouble than it was worth.) ‘Faced with the likelihood of causing harm to an individual or individuals, should one or should one not change the points?’