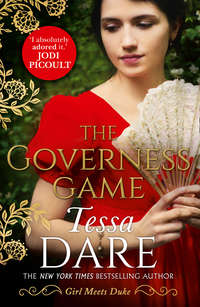

The Governess Game: the unputdownable new Regency romance from the New York Times bestselling author of The Duchess Deal

“I truly should go,” she said. “I seem to have interrupted something, and I—”

“You’re not interrupting anything. Nothing of consequence, at any rate.” He patted the back of an armchair. “Sit down.”

She numbly took the offered seat. He dropped onto the chaise across from her. From the way he sank into the cushioning, Alexandra suspected the upholstery had strained and bounced beneath many a torrid encounter.

In one last farcical swipe at decency, he ran a hand through his disheveled brown hair. “I’ve two that need looking after.”

Clocks.

Yes. Concentrate on the clocks. Those ticking things with dials and gears and numbers. They were how she made her living, and she’d been knocking on the door of every servants’ entrance in Mayfair to find more clients. She wasn’t here to gawk at the sprinkling of hair on his chest, or ponder the meaning of his black armband, or flog herself over silly fantasies that he would sweep her into his arms, confess his months of suffering for love of her, and vow to abandon his sinful ways now that she’d given him reason to live.

She slammed the lid on her imagination, buckled the strap, affixed a padlock, and then pushed it off a cliff.

This was just another business call.

He went on, “I can’t tell you much of their history. They’d been passed around by several different relations before they landed with me last autumn.”

Family heirlooms, then. “They must be precious.”

“Oh, yes,” he replied dryly. “Precious indeed. To be honest, I’ve no idea what to do with the two of them. They came along with the title.”

“The title?” she echoed.

“Belvoir.” When she did not respond, he added, “As in, the duke of it.”

A wild burst of laughter escaped her.

A duke? Oh, how Penny would gloat over having guessed that.

“Believe me,” he said, “I find it absurd, as well. Actually, I’m merely heir to a duke, for now. Since my uncle is infirm, I’ve been handed the legal responsibilities. All the duties of a dukedom, none of the perks.” He waved aimlessly in her direction. “Well, then. Teach me a lesson.”

“I . . . I beg your pardon?”

“I could inquire as to your education and experience, but that seems a waste of time. We may as well have a demonstration.”

A demonstration? Did he want to know how clockworks operated? Perhaps he meant the chronometer. She could explain why it kept the right time when clocks could lose several minutes a day.

“What sort of lesson did you have in mind?”

He shrugged. “Whatever you think I might need to learn.”

Alex couldn’t hold it in any longer. She buried her face in her hands and moaned into them.

He leaned toward her at once. “Are you ill? I do hope it’s not typhus.”

“It’s disappointment. I expected something different. I should have known better.”

He lifted an eyebrow. “What precisely were you expecting?”

“You don’t want to know.” And I don’t want to tell you.

“Oh, but I do.”

“No, you don’t. You really, truly don’t.”

“Come now. That kind of protestation only makes a man more intrigued. Just have out with it.”

“A gentleman,” she blurted out. “I expected you’d be a gentleman.”

“You weren’t wrong. I am a gentleman. Eventually, I’m going to be a peer.”

“I didn’t mean it that way. I thought you’d be the respectable, considerate, honorable kind of gentleman.”

“Ah,” he said. “Yes, that was a mistaken assumption on your part.”

“Obviously. Just look at you.”

As she spoke, her gaze drifted downward, toward his broad shoulders. Then toward the rumpled linen of his shirt. Then toward the intriguing wedge of masculine chest exposed by his open collar. The skin there was smooth and taut, and the muscular contours were defined, and . . .

And she was openly staring now.

“Look at this place. Wineglasses scattered on the table. Perfume still lingering in the air. What kind of gentleman conducts an employment interview in this . . .” She indicated their surroundings, at a loss for the word. “. . . cave of carnality?”

“Cave of Carnality,” he echoed with amusement. “Oh, I like that. I’ve a mind to engrave that on a plaque.”

“So you understand my mistake now.” The words kept pouring out of her, rash and unconsidered, and she couldn’t put them back in the bottle. She couldn’t even find a cork. “When I opened the door, I was fool enough to expect someone else. A man who’d never allow a lady to wander London with only one stocking and call it ‘nothing of consequence.’ Stockings are of consequence, Mr. Reynaud. So are the women who wear them.” She made a defeated wave at his black armband. “All of this whilst you’re in mourning.”

“Now that, I can explain.”

“Please don’t. This lesson is cruel enough already.” She shook her head. “Then there’s the telescope.”

“Hold a moment.” He sat forward. “What has a telescope to do with anything?”

“That”—she pointed with an outstretched arm—“is a genuine Dollond. A forty-six-inch achromatic with a triple object-glass of three-and-three-quarters-inch aperture. Polished wood barrel, brass draw tubes. Capable of magnifying land objects sixty times over, and celestial objects to one hundred and eighty times. It’s an instrument most could only dream of owning, and you’re letting it gather dust. It’s . . . Well, it’s heartbreaking.”

Heartbreaking, indeed.

In the end, Alex had only herself to blame. All the clues were there. His dreadful taste in books. His charming grin that made promises no man could intend to keep. And those eyes . . . They held some kind of potent, brain-addling sorcery, and he went about jostling young women in bookshops without the decency to keep them hidden beneath a wide-brimmed hat.

Her only consolation was that he’d forget this conversation the moment she left, just as he’d forgotten her before.

“Thank you, Mr. Reynaud. You’ve given me a much-needed lesson today.” She released a heavy sigh and tipped her gaze to the wall. “Antlers. Really?”

After a prolonged silence, he whistled softly through his teeth.

She rose to her feet, reaching for her satchel. “I’ll show myself out.”

“Oh, no, you won’t.” He stood. “Miss Mountbatten, that was capital.”

“What?”

“Absolutely brilliant. I would very much like to engage your services.”

Perhaps she had this all wrong. Maybe he was not the Bookshop Rake after all, but the Bookshop Madman.

Then he went and did the most incomprehensible thing yet. He looked into her eyes, smiled just enough to reveal a lethal dimple, and spoke the words she’d stupidly dreamed of hearing him say.

“You,” he said, “are everything I’ve been searching for. And I’m not letting you get away.”

Oh.

Oh, Lord.

“Come, then. My wards will be delighted to meet their new governess.”

Chapter Two

Governess?

Alexandra was speechless.

“I’ll show you upstairs.” In a display of masculine presumption, Mr. Reynaud took the satchel from her grip. As he relieved her of its weight, his hand grazed hers. The fleeting brush of warmth pushed her brain off balance. He turned and walked to the back of the room. “This way.”

She shook life into her frozen arms and followed. How could she do otherwise? He’d taken her satchel—and with it her chronometer, plus her ledger of clients and appointments. Her livelihood was literally in his hands.

“Mr. Reynaud, I—”

“They’re called Rosamund and Daisy. Aged ten and seven, respectively. Sisters.”

“Mr. Reynaud, please. Can we—”

He led her through a kitchen and up the stairs. They emerged into a first-floor corridor. She followed him down a passageway with walls covered in striped emerald silk. From the springy plush beneath her boots, she would have guessed the corridor to be carpeted in clouds. Her work took her into many a fine London house, but she never ceased marveling at the luxury.

He led the way up the main staircase, taking the risers two at a time.

“They carry the last name Fairfax, but it’s likely an adopted name. They’re natural children. Some distant relation sired a few by-blows and left their guardianship to the estate.”

As they climbed flight after flight of stairs, Alexandra could scarcely keep pace with him, much less change the topic of conversation.

“I’m sending them to school at Michaelmas term.” He added wearily, “Assuming I can bribe a respectable school into taking them.”

At last, they reached the top of the house. Alex darted forward to grab his sleeve. “Mr. Reynaud, please. There’s been some sort of misunderstanding. A grave misunderstanding.”

“Not at all. We understand one another perfectly. I’m a paltry excuse for a gentleman, as you say. I’m also no fool. That scolding you delivered downstairs was brilliant. The girls need a firm hand. Discipline. I’m the last soul on earth to teach them proper behavior. But you, Miss Mountbatten? You are just the one for the job.” He gestured at the rooms that opened off the passageway. “You’ll have a bedchamber to yourself, of course. The nursery is this way.”

“Wait—”

“Here we are.” He flung open the door.

Alexandra’s mind refused to make sense of the scene. Two flaxen-haired girls stood on either side of a bed. A beautiful bed. A grand four-poster with a lacy lavender canopy, gold-painted posts, and matching bed hangings tied back with pink cord. The bed would have been any young girl’s dream. Beneath it, however, was a nightmare. The white bed linens were streaked and spattered with crimson.

“You’re too late.” The younger of the two turned to face them, her expression eerily solemn. “She’s dead.”

“Curse it all.” Mr. Reynaud heaved a sigh. “Not again.”

Chase couldn’t believe it.

Twice in one morning. Insupportable.

He put down Miss Mountbatten’s satchel, stalked to the bed, and swiped a finger along the soiled linens. Red currant jelly, by the looks of it.

“It was the bloody flux,” Rosamund said.

Of course it was. Chase set his jaw. “From now on, there will be no jelly. None, do you hear? No conserves, no jam, no preserves of any kind.”

“No jelly?” Daisy asked mournfully. “Whyever not?”

“Because I am not eulogizing another leprosy victim covered in sores that weep marmalade! That’s why not. Oh, and no mushy peas, either. Millicent’s bout of dyspepsia last week ruined the drawing room carpet.”

“But—”

“No arguments.” He leveled a finger at his morbid little wards. “Or I’m going to lock the both of you in this room and feed you nothing but dry crusts.”

“How very gothic,” Rosamund replied.

“I’m afraid I must be going now.” The faintly voiced interruption came from Miss Mountbatten, who’d remained near the doorway.

And who, shortly thereafter, made a stealthy reach for her satchel and vanished through said doorway.

Damn it.

He strode to the map and jabbed a tack into the first empty expanse he saw. “Start packing your things.”

“There aren’t any boarding schools in the Lapland,” Rosamund said.

“I’ll put up the money to start one,” he said on his way to the door. “I hope you like herring.”

Then he ran after his newest—and please, God, not latest to quit—governess.

“Wait.” He took the stairs three at a time, vaulting over the banister so as to catch her on the next landing. “Miss Mountbatten, wait.” With a flailing swipe, he caught her by the arm.

They stood wedged in the stairwell. She was short, and he was tall. The crown of her head met him mid-sternum. Conversation was comically impossible. He released her arm and took two steps downward so he might look her in the eye.

Her gaze nearly knocked him down the stairs. For a woman of small stature, she made a prodigious impact. A delicate snub of a nose, olive skin, and a glossy knot of midnight-black hair. And fathomless dark eyes that pulled on something deep in his chest. He needed a moment to collect himself.

“Millicent is Daisy’s doll. She kills the thing at least once a day, but—” Curse it, he’d left red smudges on her sleeve, and God only knew what substance she presumed it to be. “No, it’s not what you think. It’s only red currant jelly.” He held up his stained index finger. “Here, taste for yourself.”

She blinked at him. “Did you just invite me to lick your finger?”

He wiped his hand on a fold of his shirt. God, he was making a hash of this. If she worried for her virtue, that wouldn’t aid his case. Any sensible young woman would hesitate to accept employment in the house of a scandalous rake—even if the rake’s wards were perfect angels. Chase’s wards were incorrigible, morbid hellions.

In fact, the post offered few advantages, save one.

“I’ll pay you handsomely,” he said. “An astronomical sum.”

“There’s been a mistake. I came to offer my services as a timekeeper. I’m not a governess. I’ve no training, no experience. And governesses are gently bred women, aren’t they? I don’t meet that qualification, either.”

“I don’t care if you’re gently bred, roughly bred, or a loaf of brown bread with butter. You’re educated, you understand propriety, and you’re . . . breathing.”

“I’m certain you’ll find someone else to fill the post.”

“The post has been filled. And vacated. And filled and vacated several times over. Sometimes multiple times in one day.”

You’re not doing your offer any favors, Reynaud.

“But you’re not like the rest of those candidates,” he hastened to say. “You’re different.”

She was different.

Here was a woman who’d just schooled him within an inch of his dignity. She thought him a crude, unintelligent layabout. A paltry excuse for nobility and a waste of good tailoring. Miss Mountbatten—quite wisely—wanted nothing to do with him.

And Chase was positively desperate to keep her near.

The desire rising in him wasn’t physical. Well, it wasn’t entirely physical. She was pretty, and he appreciated a forthright woman who knew what she was about. But mingled with the attraction was something more. A wish to impress her, to be worthy of her approval.

She made him want to be better. And wasn’t that an ideal quality in a governess? He had to keep this woman in his employ.

“It’s only for the summer,” he said. “A year’s wages, for a few months of work.”

“I’m sorry.” She sidestepped him and continued down the stairs.

“Two years’ wages. Three.”

“Mr. Reynaud . . .”

Chase caught her at the door. “It comes down to this. Those girls need you.”

He waited until she looked at him, and then he reached into his arsenal of persuasion.

A hard swallow, indicating a manful struggle with emotion.

An intense, searching gaze.

The husky whisper of a confession.

“Miss Mountbatten.” Hell, why not go for it all? “Alexandra. I need you.”

There. That line worked on every woman.

It didn’t work on her.

“No, you don’t.” A flash of irony crossed her face. “Don’t worry. You’ll forget me soon enough.”

And then she did what Chase yearned to do, often. She flung open the door, fled the house, and didn’t once look back.

Chapter Three

Two hours later, Alexandra found herself standing on a Billingsgate dock.

Terrified.

The June morning was soaked with sunshine, but she’d left Mr. Reynaud’s house in a mental fog. Her distraction was such that she’d made two wrong turnings on her well-trod path to London Bridge, and now she had missed the noon coach to Greenwich.

The rational solution was to take a wherry down the Thames. However, the mere sight of the boat sent an irrational shiver rippling down her spine.

I can’t. I just can’t.

But what were her alternatives?

If she risked waiting for a later coach, the bridge would be madness, crushed with carts going nowhere. She’d never make it home before dark.

She could call off the journey entirely. However, calibrating the chronometer once a fortnight was her signature promise to customers. They paid for precise Greenwich time, and she delivered it, without fail.

Just do it, she told herself. It’s time to move past this, you ninny. You were raised on a ship, after all. A merchant frigate was your cradle.

Yes. But it had nearly been her coffin, too.

Nevertheless, here she stood ten years later. Alive. She could survive a brief jaunt down the Thames to Greenwich.

She could do this.

As the boatman loaded bundles and helped passengers into the wherry, she hung back, waiting until the last possible moment.

“Are you coming, miss, or ain’t ye?”

“I’m coming.” Alex accepted his hand and boarded the boat, wedging herself on a plank between two older women and settling her satchel on her lap.

When the boatman cast off the ropes mooring the wherry to the dock, she decided to set her mind on something else. Now that she knew better than to fantasize about Chase Reynaud, a good portion of her brain was suddenly available for other pursuits. Naming all the constellations bordering Ursa Major, perhaps.

Drat. Too easy. She rattled through the list in moments—Draco, Camelopardalis, Lynx, Leo Minor, Leo, Coma Berenices, Canes Venatici, Boötes—and there her concentration fractured. Once the first oar hit water, she couldn’t piece a single thought together.

She balled her hands in fists and dug her nails into her palms, attempting to distract herself by means of pain. That didn’t work, either. She felt nothing but the lift and roll of water beneath the craft. That terrifying sensation of coming unmoored. Drifting untethered.

No. She couldn’t do this after all.

Alex pushed to her feet, making her way to the edge of the boat. They hadn’t yet pushed off. Still just a foot from the dock. “Wait,” she told the boatman. “I’ve just recalled something. I need to disembark.”

“Too late, miss. You can cross again when the boat comes back.” He moved to push off with the oar.

“Please.” She was begging now, her voice cracking. “It’s urgent. I must get off the boat. I . . .”

“Sit down, woman,” he barked, bracing his oar to push off.

Alex was frantic, wild. She scrambled atop the rail of the boat, wavering on her toes. The other passengers cried out in alarm as the boat tipped to one side. The boatman gripped the hem of her frock, attempting to yank her down into the boat. His grasping only increased her desperation.

She quickly judged the distance between the wherry and the dock. She could make it, she thought, but only if she jumped.

And jumped now.

She made the leap.

Her judgment wasn’t faulty. If not for her boot slipping on the wherry’s edge, she would have made the jump cleanly. Instead, she plunged into the water with a splash, gasping as she went and catching a foul, wretched mouthful of the Thames.

When she surfaced, a man on the dock caught her under the arm, pulling her up and helping her scramble out of the river.

On the dock at last, she sputtered and choked with relief.

That’s when she noticed it had gone missing. Her satchel. The chronometer. When she’d tumbled into the river, it had fallen from her grip and sunk into the depths.

Her livelihood, gone.

A sob wrenched from her body, like a droplet wrung from damp cloth.

One more thing the water had taken from her. It was the insatiable monster in her life. Jonah’s whale. Devouring everything she loved, but spitting her back out, again and again, more lost and lonely than ever.

And once more, there was nothing to do but pick herself up and start over.

“Well? What do you think?” Chase spread his arms and turned slowly, putting on a display of his unfinished apartment. “I’m remaking it into a manly retreat.”

Barrow stared at the shambles of what had formerly been the housekeeper’s quarters. “Where are Mrs. Greeley’s things?”

“I’ve moved her to a bedchamber on the second floor. Far superior accommodations.”

“Dare I ask the reason behind this renovation?”

Chase went to pour them two tumblers of brandy. “Until Rosamund and Daisy go off to school, I need somewhere to escape.”

“A grown man escaping from two little girls. Now that’s rather pathetic, isn’t it?”

“Come now. I don’t know what to do with children. There’s no point in troubling to learn. I’m not going to sire any of the grimy things. Even if I wished to marry, there’s no use searching for a wife. You’ve laid claim to the best woman in England.”

“This is true.”

John Barrow Sr. had been Chase’s father’s solicitor, and from the time Chase and John Jr. had been boys, it was understood they would continue the family tradition. Also understood, but never spoken of, was the reason why. They were half brothers. Chase’s father had impregnated a local gentleman’s daughter, and his loyal solicitor had taken it upon himself to marry her and raise the child as his own.

So Chase and John had grown up together, sharing both tutors and paddlings. Squabbling over horses and girls. Despite the disparity in their social ranks, they’d maintained a close friendship through school and beyond. A damned lucky thing, on Chase’s part. Now, with a dukedom at stake, he needed a trusted friend to help manage the estate.

“How is my godson?” Chase asked. “Speaking of grimy things.”

“Charles is living up to his namesake, unfortunately.”

“Ah. Charming every woman in sight.”

“Lying about while everyone else does the work.”

“I’ll have you know,” Chase said indignantly, “I have been hard at work during your absence. Witness the renovation in progress around you. I built that bar myself, thank you very much. It only needs a few coats of lacquer. And if that’s not sufficient for you—in the past week alone I’ve gone through a decade of bank ledgers, given seven orgasms, and interviewed five governesses. And no, none of the governesses were recipients of the orgasms, although a few of them looked as though they could use one.”

“Five candidates, and you didn’t find one to hire?”

“I hired each and every one of them. None of them lasted more than two days. In fact, the latest didn’t even make it past the nursery door. A pity, too. I had hopes for her. She was different.”

Normally, Chase was the one coaxing women to leave. He wished he’d been able to make Alexandra Mountbatten stay.

Barrow peered at him. “That was odd.”

“What was odd?”

“You sighed.”

“That’s not odd at all. Not lately.”

“Well, it was the tone of the sigh. Not weary or annoyed. It was . . . wistful.”

Chase gave him a sidelong look. “I have never been wistful a day in my life. I am entirely devoid of wist.” He tugged on his waistcoat. “Now if you’ll excuse me, I have an engagement this evening. The women of London can’t pleasure themselves, you know. I mean, they can pleasure themselves. But on occasion they generously let me have a go at it.”

“Who is she this time?”

“Do you really care?”

“I don’t know. Do you?” Barrow gave him a look that cut like a switch. “Someday you’ll have to put a stop to this.”

Chase bristled. “You are a solicitor. Not a judge. Spare me the moralizing. I make women no promises I don’t intend to keep.”

In truth, he made no promises at all. His lovers knew precisely what he had on offer—pleasure—and what he didn’t have to give—anything more. No emotional attachment, no romance, no love.

No marriage.

As war, illness, and his own unforgivable failures would have it, in the space of three years, Chase had gone from fourth in line for his uncle’s title to the presumptive heir. It was a development few could have imagined, and one that nobody, Chase included, had desired. But once his uncle let go the thin cord connecting him to life, Chase would become the Duke of Belvoir, fully responsible for lands, investments, tenants.