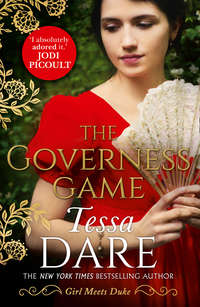

The Governess Game: the unputdownable new Regency romance from the New York Times bestselling author of The Duchess Deal

There was only one traditional responsibility he wouldn’t take on.

He wouldn’t be fathering an heir.

The Belvoir title should have been Anthony’s by rights, and Chase refused to usurp his cousin’s birthright. His line was the crooked, rotting branch of the family tree, and he meant to saw it off. Cleanly and completely. It was the least he could do to atone.

And since there would be no marriage or children in his future, didn’t he deserve a bit of stolen pleasure in the present? A touch of closeness, now and then. Whispered words in his ear, the heat of skin against skin. The scent and taste and softness of a woman as she surrendered her pleasure to him.

A few scattered, blessed hours of forgetting everything else.

“Which of these would look better hanging above the bar?” Chase held up two paintings. “The fan dancer, or the bathing nymphs? The nymphs have those delightful bare bottoms, but that saucy look in the fan dancer’s eyes is undeniably captivating.”

Barrow ignored the question. “So if you haven’t found—or kept—a governess, who’s minding the girls?”

“One of the maids. Hattie, I think.”

No sooner had he said this than screams and a thunder of footsteps came barreling down the stairs.

Hattie appeared in the doorway, her hair askew and her apron slashed to tatters. “Mr. Reynaud, I regret to say that I cannot continue in your employ.”

He cut her off. “Say no more. You’ll have severance wages and a letter of character waiting in the morning.”

The maid fled, babbling with gratitude.

Once he heard the door close, Chase sank into a chair and buried his face in his hands. There went his plans for the evening.

“Now that,” Barrow said, “was a despairing sigh.”

The front doorbell rang. “I’d better answer that myself.” Chase rose to his feet. “I’m not certain I have any servants remaining to do it.”

He opened the door, and there she was: Miss Alexandra Mountbatten. Soaked to the skin, her dark hair dripping.

He tried not to look downward, and when he did so anyway, he told himself it was out of concern for her well-being. He was concerned for her well-being. Especially if one defined “well-being” to mean “breasts.”

So he noticed her nipples. What of it? He spent a ridiculous portion of his waking hours thinking of nipples. Hers just happened to be the nearest, and the most chilled. Hard as jewels beneath her bodice. Red as rubies, maybe. Or pink topaz, pale amethyst . . . ? No. Given her dark coloring, they were most likely a rich, polished amber.

The chattering of teeth pulled his attention back upward. God, he was every bit the repulsive cad she’d called him, and more.

She caught her bluish bottom lip beneath her teeth. “Is the post still available?”

He didn’t hesitate. “Name your price.”

“Ten pounds a week. Another hundred once they’ve gone off to school.”

“Five pounds a week,” he countered. “And two hundred once they’ve gone off to school.”

“One more thing.” From beneath a dripping umbrella of eyelashes, her eyes met his. “I want the use of your telescope. The one down in your . . .”

He crossed his arms and leaned against the door. “Cave of Carnality?”

“Yes.”

Chase supposed he had offered her an astronomical sum. Besides, he wasn’t making use of it. “Very well.”

She sniffled. “I’ll report first thing tomorrow.”

He caught her arm as she turned to leave. “Good God. At least come in and get warm first.”

I’ll warm you.

He chased the errant thought away, like he would an eager puppy. She was in his employ now, and there would be no such ideas. Even he had that much decency.

“Thank you, no. I’ll need to pack my things.”

She walked away, leaving a trail of sloshy bootprints. Chase looked about the entrance hall for an umbrella and found none. Of course there wouldn’t be a greatcoat, either, not in the middle of June.

With a curse, he bolted through the door empty-handed and dashed after her. “Miss Mountbatten.”

She stopped and turned on her heel. “Yes?”

“You’re not leaving dressed like that.” He shrugged out of his tailored topcoat, shaking it down his arms.

“I can’t accept your coat.”

“You can, and you will.” He swung the coat around her shoulders and tucked it tight. She was so petite, the garment’s hem nearly reached her boots. The sight was equal parts comic and piteous.

“But—”

He jerked on the coat’s lapels, drawing them together. “Yes, yes. I know you’re bossy. As a governess, it’s to your credit. But I’m your employer, as of two minutes ago. For as much as I’m paying you, I expect you to do as I say.” As he worked the buttons through their holes, he went on. “Given the alacrity with which you fled my offer of employment this morning, it’s obvious something dire occurred to make you change your mind. If I were any sort of decent fellow, I would ask about that dire situation and sort it out. Seeing as I am a selfish blackguard, however, I intend to take full advantage of your lowered circumstances.”

There, now. He had her buttoned, and he stood back to look at her. She looked like a sausage roll.

A soggy sausage roll.

A soggy, confused sausage roll with slick ebony hair that would feel like satin ribbons between his fingertips.

Right. He dragged himself back to the point.

“I need a governess. Not just any governess, Miss Mountbatten. I need you. Which is why I will not have you walking home in the rain and catching the grippe.”

“But it isn’t—”

“I insist. Most insistently.”

She blinked at him. “Very well.”

Finally, she heeded his demands. She walked down the pavement and turned the corner, disappearing from view.

As he returned to the house, Chase took note of an unexpected sensation. Or rather, the lack of an expected sensation. Miss Mountbatten had appeared at his front door soaked to the skin, and he hadn’t yet felt a single raindrop.

He tipped his head to the sky. Strange. Nothing overhead but the periwinkle and orange streaks of twilight.

It wasn’t raining.

In fact, now that he thought of it, it hadn’t rained all day.

Chapter Four

At home, Alexandra unwrapped herself from Mr. Reynaud’s coat and hung it on a peg. She’d likely ruined the thing. The garment had smelled deliciously of mint and sandalwood when he’d wrapped it about her shoulders. Now it reeked of the Thames.

After bathing and changing into a clean shift and dressing gown, she followed the scent of baking biscuits down to the kitchen. Thank heaven for Nicola and freshly baked biscuits.

She sat down at the table and laid her head on folded arms. “Hullo, Nic.”

Nicola whisked a tray of biscuits from the oven. A sweet, lemony steam permeated the kitchen. “Goodness, has the day gone already?”

“It has, I’m afraid.” And what a day it had been. Alex lifted her head. “Do you remember the Bookshop Rake?”

“The Bookshop Rake?” Nicola frowned. “It’s not a poem or limerick, is it? I’m useless at those.”

“No, it’s a man. We met with him in Hatchard’s last autumn. I was carrying a stack of your books in one arm, and reading one of my own with my free hand. He and I collided. I was startled, dropped everything. He helped me gather up the books.”

Nicola piled the biscuits onto a plate and carried it to the table, setting it between them.

“Tall,” Alex prompted. “Brown hair, green eyes, fine attire. Handsome. Flirtatious. We all decided he must be a terrible rake.” And we didn’t guess the half of it. “Penny teased me for months. Surely you must remember.”

Nicola lowered herself into a chair, thoughtful. “Maybe I do recall. Was I buying natural history books?”

“Cookery and Roman architecture.”

“Oh. Hm.” Biscuit in one hand and book in the other, Nicola was already absorbed in other thoughts.

Alexandra reached for a biscuit and took a resigned bite. That was Nicola for you. She jettisoned useless information like ballast. She needed the brain space to cram in more facts and theories, Alex supposed. And to come up with her ideas.

When Nicola was concentrating, she set aside everything else. She would neglect the passing of hours and days, if not for the odor of burnt cakes coming from the kitchen, or the clamor of the twenty-three—

Cuckoo! Cuckoo!

The twenty-three clocks.

So it began. The chiming, ringing, chirping, and bonging from timepieces that stood, hung, sat—even danced—in every corner of the house.

Alexandra couldn’t complain about the noise. Nicola’s clocks were the only reason she could afford to live in a place like Bloom Square. In exchange for a room in her friend’s inherited Mayfair house, Alex bartered her timekeeping services. The din was loud enough when they all struck the hour in unison . . . but if they fell out of synchrony, the noise went on for ages.

After the last chime sounded, Alex spoke to whatever fraction of her friend’s divided attention she could command. “He offered me a post. The Bookshop Rake.”

“The Bookshop Rake?” Lady Penelope Campion burst through the kitchen door, flushed and breathless, holding a flour sack in one hand and clutching a bundle to her chest with the other. “Did I hear mention of the Bookshop Rake?”

With a soft moan, Alex laid her head on the table again.

“Oh, Alexandra.” Penny dropped the sack, sat down beside her, and clutched her arm. “You’ve found each other at last. I knew you would.”

“It wasn’t like that. Not in the slightest.”

“Tell me everything. Was he just as handsome as he was in Hatchard’s?”

“Please, Penny. I beg you. Hear me out before you start dreaming up names for the children.”

“Oh!” Penny snapped her fingers. “I nearly forgot the reason for my visit. It’s Bixby’s cart. He was chasing after the goslings, and he popped the axle out of place.” At the sound of his name, the rat terrier poked his head out from the blanket. Penny clucked and fussed over him. “What a little scoundrel you are. If you had all four legs, I shouldn’t know what to do with you.”

Nicola reached for the sack and withdrew the contraption inside—a tiny cart she’d rigged up to serve in place of Bixby’s hind legs. She turned it over, inspecting the axle. “Won’t take but a moment.”

“There, now. Alex, you were saying . . . ?”

“She was saying he offered her work.” Nicola retrieved her little caddy of hand tools and sorted through the wrenches and pliers. “That’s all.”

“Of course he offered her work,” Penny said. “As a pretext. That way he can see her once a week. He’s taken with her.”

Alex placed both hands on the table. “If you’re going to make up your own tale, I can retire to bed.”

“No, no.” Penny fed Bixby a biscuit. “We’re listening.”

Alexandra poured herself a cup of tea and began at the beginning. By the time she reached the end of her tale, the plate of biscuits had been devoured to crumbs and Bixby was racing circles around the table with the aid of his cart.

“He ran after you and gave you his coat.” Penny sighed. “So romantic.”

“Romantic?” Nicola made a face. “Did you miss the bit where he keeps two little girls locked in the attic and feeds them nothing but dry crusts?”

“Not at all,” Penny returned. “It’s one more reason to accept. Just think of how much those orphaned girls need her.”

Alex rubbed her temples. How she missed Emma. She adored all three of her friends, but Emma was the most understanding among them. A former seamstress, she’d once worked for her living, too. At the moment, however, both Emma and her heavily pregnant belly were happily ensconced in the country.

Nicola tsked. “Alex, I can’t believe you accepted the post.”

“I couldn’t say no. He offered me an astronomical sum. I will make more in two months than I could hope to make in two years of clock setting. Besides, after what happened at the dock, I didn’t have a choice.”

“Of course you had a choice. You might have asked your friends for help,” Penny said. “We are always here if you need us.”

“We could have scraped together the money to replace your chronometer.” Nicola looked up from her tinkering. “And you know you are welcome to stay with me as long as you wish.”

“That’s lovely of you both. But what if you loaned me money I couldn’t repay?” She turned to Nicola. “What if you decide to marry, and your husband doesn’t want a spinster in the house?”

Nicola chuckled. “Me, married. Now that is a laugh.”

“No, it isn’t,” Penny protested. “It’s entirely likely that a dashing gentleman will fall in love with you and propose.”

“But would I want to accept? That’s the question.”

Alexandra was grateful the conversation had veered to Nicola. The risk she was taking was so enormous, she couldn’t contemplate it. No more than a snowflake could contemplate summer. If she failed in this post, she could lose any chance of supporting herself thereafter. And as much as she adored her friends, Alex craved a place of her own.

A home.

Even a tiny cottage in the country would do nicely, so long as it was hers. She longed to feel real earth beneath her feet and let her toes burrow into the soil like roots. No more drifting on tides.

However, her plan required money. A large amount of money. She scoured the papers for notices of cottages to let and made careful note of the rents. She’d drawn up a budget, then calculated the lump sum she’d need to have saved in the bank in order to live on the interest.

Four hundred pounds.

In three years, she’d managed to save fifty-seven.

Now she had the chance to walk away with two hundred and fifty pounds by Michaelmas. For that sum, she would shovel the Shepherd Market middens during the height of summer. Naked.

“I have to go upstairs and pack my things. I’ve promised to report tomorrow morning.”

“Be careful of him, Alex,” Nicola said. “If he is truly a rake, as you say.”

“Believe me, there’s nothing to fear. He isn’t interested in me. He didn’t even remember meeting me. Apparently I was quite forgettable.”

“Stop.” Penny stole Alex’s hand. “I will hear none of that. You are not forgettable.”

Dear, sweet Penny, with her heart for lost and broken creatures. No doubt she recalled the name and personality of every last mouse in the cupboard. But most people weren’t Penny, and this wasn’t the first time Alexandra had raised her hopes, only to be disappointed.

“It doesn’t matter whether he recalled me or not. I’ll be looking after his wards. I will scarcely see him.”

“Oh, you will see him,” Penny said. “Especially if you go wandering about the house at night. Try the library first.”

“Lock yourself in your room,” Nicola countered. “I’ll make you a deadbolt.”

“Stop, the both of you. I’m accepting a well-paid situation for the summer. Until yesterday, I was setting clocks; tomorrow, I begin as a governess. It’s not romantic. It’s not dangerous. It’s work.”

“You don’t have to be sensible all the time,” Penny said.

Easy enough to say, for a lady with a house of her own and a thousand pounds a year. Penny and Nicola didn’t have to be sensible all the time, perhaps, but Alexandra did. She couldn’t afford to be swept away.

Fortunately, there was no longer any chance of that happening. Never mind that he’d ensorcelled every other woman in London. Alex knew better. Now that she’d seen his shameless nature, Chase Reynaud had lost all appeal. She would never be tempted by him again.

Not his smile.

Not his eyes.

Most certainly not his bare chest.

Nor his voice, forearms, wit, charm, or large feet.

And not his warm, delicious-smelling coat, either.

Oh, Alex. You are doomed.

Chapter Five

Alexandra reported for duty the following morning. This time, she knew to knock at the front door. And, to her profound relief, the housekeeper answered.

Mrs. Greeley looked her up and down. “I thought you were the girl who sets clocks.”

“I was,” Alexandra answered. “Apparently now I’m a governess.”

“Hmph. By the end of the day, you’ll be the girl who sets clocks again.” She waved Alex toward the stairs. “Come, then. I’ll show you to the nursery. I’ll have Jane prepare you a room, and Thomas will bring up your trunks in a bit.”

Alex suspected Jane and Thomas would be waiting to see if she lasted the morning before they went to the trouble.

When she entered the nursery today, she did not come upon another murder scene. Thank goodness. This time, she had the chance to take a proper look at the surroundings—and what she took in left her breathless.

The room was a fairyland. All done up in frothy white and buttery yellows and blushing pinks. Like the window of a confectionery. White wainscoting lined the bottom half of the room, and here and there painted ivy tendrils climbed the sky-blue walls. The room offered no shortage of playthings. Alex saw rocking horses, miniature tea sets, and marionettes. An upholstered window seat had been wedged under one of the eaves, and beneath it ranged a shelf overflowing with books.

Considering the freshness of the paint and the lavish quality of the furnishings, she deduced two things: First, the room had been done up expressly for these two girls. Second, no expense had been spared.

“That one there is Rosamund.” The housekeeper pointed to the elder of the two girls.

Rosamund sat reading a book in the window seat. She didn’t look up.

“And that’s Daisy,” Mrs. Greeley said.

Daisy acknowledged her at least, dropping in a slight curtsy. Her eyes, pale blue and wide as shillings, were downright unsettling. In her arms, she cradled a doll. A quite expensive one, with a head carved from wood, covered with gesso, and painted with rosy cheeks and red lips.

Alexandra crossed the room to Daisy’s side. “I’m most pleased to meet you, Daisy. This must be Millicent.”

Daisy took a step in retreat. “Don’t draw too near. She has consumption.”

“Consumption? I’m sorry to hear it. But I’ve no doubt you’ll nurse her to a swift recovery.”

The girl shook her head gravely. “She’ll be dead by tomorrow morning.”

“Surely she won’t—”

“Oh, she will,” Rosamund said dryly, speaking from the window seat. “Best to have a few words prepared.”

“A few words prepared for what?”

Without moving her lips, Daisy made a few dry, hacking coughs. “Millicent needs quiet.”

“Yes, of course she does. Do you know what I hear is the best remedy for consumption? Fresh air and sunshine. A stroll to the park should set her up nicely.”

“No outings,” Mrs. Greeley declared. “They’re to focus on their lessons. Mr. Reynaud was very clear.”

“Oh. Well, then. Perhaps we can soothe Millicent another way.” She thought on it. “Perhaps tea with heaps of milk and sugar, and a dish of custard. What do you think, Daisy? Shall we give it a go?”

“No custard,” Mrs. Greeley said.

“They’re not allowed custard, either?”

“That’s Daisy’s fault,” Rosamund explained. “She gave Millicent a nasty case of the grippe and used it for phlegm.”

Daisy shushed them all, clutching the doll tightly to her chest. “Please. Allow her some peace in her final hours.”

“I won’t disturb your peace if you don’t disturb mine,” Rosamund said. “You had better not wake me with hacking and wheezing in the middle of the night.”

Now that she had Rosamund’s attention, Alex decided to try with her. “What are you reading?”

“A book.” She turned a page.

“Is it a storybook?”

“No, it is a book of practical advice. How to Torture Your Governess in Ten Simple Steps.”

“She’s likely writing the second volume,” Mrs. Greeley muttered. “The cook will send up your luncheon at noon.”

The housekeeper disappeared, leaving Alexandra alone with her two young charges. Her stomach fluttered with nerves.

Steady, she told herself. Rosamund and Daisy were only girls, after all. Girls who’d been orphaned and passed from home to home, guardian to guardian. If they greeted a newly arrived governess with mistrust, it was only natural. In fact, it was sensible. Alex had been an orphan, too. She understood. It would take time to build trust.

“We won’t have any lessons today,” she announced.

“No lessons?” Rosamund lifted an eyebrow from behind her book. “What are we going to do all day?”

“Well, I intend to acquaint myself with the schoolroom, then perhaps write a letter or read a book. How you spend the day is yours to decide.”

“So you intend to bilk our guardian for wages while letting us do as we please,” the girl said. “I approve.”

“That is not my intent, but we have the whole summer for lessons. Of course, if you wished to begin today, I could—”

Rosamund put her nose back in her book.

Alex was relieved. The truth was, she had no idea where to even start. Being a governess hadn’t sounded so difficult last night—she had an education, after all—but now that she was here, she felt at a loss.

While the girls were occupied, Alex had a look at her surroundings. One side of the space had been designated as a schoolroom. She found it furnished with just as much attention and thought as the nursery. Two child-sized writing desks, an adult-sized table with a wide, flat top, and a bedsheet-sized slate hanging on the wall. On the slate, in careful script, someone had chalked five words:

Letters

Ciphers

Geography

Comportment

Needlework

Alex moved on to a world map affixed to the wall. The continents were peppered with tacks in a seemingly random arrangement. Malta, Finland, Timbuktu, a speck of an island in the Indian Ocean, the Sahara Desert.

Daisy appeared at her elbow. “Those are the places Mr. Reynaud says he’s sending us to boarding school.”

Alex considered the options. “Well, if I were you, I’d take Malta in a heartbeat. It’s quite lovely. Surrounded by azure seas.”

“You’ve been to Malta?”

“I’ve been all sorts of places. My father was a sea captain.” Alex rearranged the tacks, pushing them into common trading ports. “Macao. Lima. Lisbon. Bombay. And I was born near here.” She placed the final tack.

“Where’s that?”

“Read for yourself.”

Daisy flashed a glance over her shoulder, then whispered, “I can’t.”

“Ma-ni-la.” Alex sounded out the syllables for her. “It’s a port in the Philippine Islands.”

Seven years old, and she couldn’t yet read. Oh, dear.

“Say, Daisy. I’m wondering if we have enough pencils and bits of chalk. Would you help me count them out?”

“I—”

“Daisy,” Rosamund interrupted sharply. “I think I hear Millicent coughing.”

As her sister went to nurse her ailing patient, Rosamund fixed Alex with an unflinching—and unmistakable—look. Stay away from my sister.

Alex’s spirits dipped. The challenge before her was already intimidating. She had no teaching experience, the younger of her two charges had not yet learned to read, and her employer would be completely unhelpful.

However, it was plain that the most formidable obstacle in this entire endeavor would come in the shape of a mistrustful, strong-willed, ten-year-old girl.

So. The war of wills began here.

If she didn’t want to leave this house penniless, it was a war Alexandra had to win.

Chapter Six

That evening, Chase stood in the doorway of his governess’s bedchamber, waging a fierce battle with temptation.

He’d stopped by her room with the most innocent of motives. He intended to see that she’d settled in, and be assured that the accommodations were to her liking.