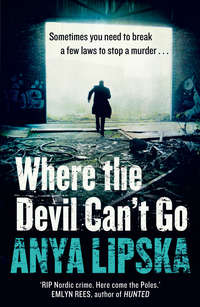

Where the Devil Can’t Go

He ordered the drinks and, leaving a twenty on the bar to pay for them, strolled to the toilets. After using the urinal, he lingered at the washbasin, combing his hair in the mirror and praying nobody took him for a pedzio. Just as he expected, a minute or two later, a shaven-headed, rail-thin guy in a hooded jacket slid up to the sink next to him, turned on the taps, and made a pretence of washing his hands.

‘Wanna buy Mitsubishi?’ he asked in Polish, without turning his head.

Janusz had a pretty good idea he wasn’t being offered a used car. Pocketing the comb, he raised a non-committal eyebrow.

‘It’s good stuff,’ the guy urged, ‘double-stacked …’ Suddenly, he found his sales pitch interrupted as his face was brought into violent and painful contact with the mirror.

‘What the fu …?!’ He gazed open-mouthed at his contorted reflection and scrabbled at the back of his neck where Janusz’s rocklike fist gripped his balled-up hood.

Janusz shook his head, gave him another little push for the profanity.

‘A word of advice, my friend. The undercover policja are all over this place. Apparently, some scumbag is selling drugs to youngsters.’

The guy tried to wipe snot and blood from his nose.

‘Your best move would be to take your … business up to the West End, and rethink your policy on selling to anyone under twenty-one.’ Janusz bent his head down to the guy’s level, locked eyes with him in the mirror. ‘In fact, if I was you,’ he said softly, ‘I’d insist on seeing a driving licence.’

Straightening up, he released the guy, who bolted, and turning on the taps, gave his hands a thorough soaping. He frowned at his reflection. Had Adamski been dealing Ekstasa here? It could explain a lot: his bizarre and unpredictable behaviour, the glazed look Weronika wore in the dirty photos, his sudden acquisition of enough cash to buy a BMW. It might explain that fracas with the klub bouncer, too.

Rejoining Justyna, he told her he’d been offered drugs in the toilets. He hoped she might take the bait, confirm that Adamski was a dealer, but she just lifted a shoulder, non-committal.

‘When I was a student,’ he said, ‘the only way to get high, apart from booze, was the occasional bit of grass. A guy I knew started growing it on his bedroom windowsill – in the summer the plants would get really huge. Anyway, one day, his Babcia was cooking the family dinner when she ran out of herbs,’ he looked up, found her smiling in anticipation.

‘The old lady decided that Tomek’s plant was some kind of parsley, and chopped a whole bunch of the stuff into a bowl of potatoes. Luckily, it wasn’t all that strong. All the same, he said that after dinner, when the state news came on – you know, the old Kommie stuff about tractor production targets being broken yet again – the whole family started cracking up, laughing their heads off, and found they just couldn’t stop.’

Justyna met his gaze, a grin dimpling her cheeks.

‘Anyway, Tomek said that the night went down in family history,’ Janusz went on. ‘And whenever his parents told the story, they always said the same thing: “That batch of elderberry wine was the best that Babcia ever made!”’

They laughed together, any remaining ice between them fully broken. He seized the moment to ask, ‘But in London, you can get anything, of course. Kokaina, Ekstasa, so on …’

‘Sure,’ she agreed. ‘If you are a fucking idiota.’ She sucked some juice up through her straw. ‘One of my friends died, back home, from sniffing glue. He was fifteen.’ She shook her head. ‘If I’d taken drugs I’d probably be dead like him, or even worse – still stuck in Katowice.’ They shared a wry grin: the joke crossed the generational divide.

Seizing the moment, he asked, ‘You think Pawel messes about with drugs, don’t you?’

She hesitated, then met his eyes. ‘I think so, yes. How else does someone like him make such money?’

Janusz made his move.

‘You know that pani Tosik has hired me to find Weronika,’ he said. Justyna gave a barely perceptible nod. ‘I can see it’s difficult for you – you are loyal to your friend. But I think you are right to be worried that this boyfriend of hers might put her in danger.’

She played with the straw in her glass, a frown creasing her forehead.

‘I’m not asking you to betray her trust – just to give me a few pointers,’ he went on. ‘It would help if I knew how Adamski talked her into going off like that.’

The girl took a big breath, let it out slowly. Then, speaking in a low voice, she told him that two weeks earlier, while pani Tosik was out getting her hair done, Weronika had locked herself away in her bedroom above the restaurant. Suspecting that something was going on, Justyna kept knocking and calling her name through the door.

‘In the end, she let me in,’ she said. ‘She was bouncing off the walls with excitement. Then I saw the half-packed suitcase on the bed. At first, she wouldn’t tell me what was going on, said Pawel had sworn her to secrecy.’ A line appeared between Justyna’s dark eyebrows. ‘But Nika couldn’t keep a secret to save her own life. In the end she showed me the ring she was wearing on a chain round her neck.’

‘They were engaged?’ asked Janusz, incredulous. An image of Weronika in a G-string posing for the camera, her eyes unfocused, swam before him and he tensed his jaw. Some fiancé, he thought.

Justyna nodded. ‘She was as excited as a little child on Christmas Eve,’ she said, unable to suppress a smile at the memory.

‘Did she say where she was going, where they would be living?’

She shook her head – but judging by the way her gaze slid away from his, he suspected she was lying.

‘She said they’d be leaving London soon. Pawel had some business to finish up, and then they were going back home to get married.’ She popped her eyes. ‘All this, after she’d known him just a few weeks!’

Janusz was touched by Justyna’s concern. She couldn’t be more than five or six years older than Weronika, but it was clear the younger girl brought out the mother hen in her.

‘I tried to talk her out of it,’ she went on. ‘I said, imagine how upset your mama will be when she hears her little girl has run off with some man she barely knows.’

‘But it did no good?’

‘She went a bit quiet,’ recalled Justyna. ‘But then she said Mama would be fine so long as no one cut off her supply of cytrynowka,’ she shot him a look. The sickly lemon wodka was a notorious tipple of street drunks – and alcoholic housewives. ‘Nika told me she would often come home from school and find her lying unconscious on the kitchen floor.’

Apparently, Mama had been little more than a child herself when she’d fallen pregnant with Weronika. The little girl had grown up without a father and the only family apart from her chaotic drunk of a mother had been a distant uncle who visited once in a blue moon.

Poor kid, thought Janusz. It was hardly surprising that after leaving home, she should fall head over heels in love with the first person who showed her any affection – like a baby bird imprinting on whoever feeds it, however ill-advised the love object.

By now, there was standing room only in the bar area, and the crowd was encroaching on the small table where Janusz and Justyna sat. The thump thump of the music, the shouted conversations and the bodies pressing in all around set up a fluttering in Janusz’s stomach. So when the girl said she ought to go, she had an early start at the restaurant the next day, he felt a surge of relief.

He insisted on walking Justyna to her flat, which was a mile away to the west, the other side of Stratford, beyond the River Lea. The route took them through the centre of town, where the music and strident chatter spilling from the lit doorways of pubs and clubs and the clusters of smokers outside suggested the place was just waking up, although it was gone eleven and only a Tuesday. As they passed the entrance to an alleyway beside one pub Janusz heard urgent voices and, through the gloom, saw two men pushing a smaller guy up against the wall. He froze, muscles bunching, but a second later the scene came into focus. The little guy was catatonic with drunkenness, head drooping and limbs floppy, and the other two, weaving erratically themselves, were simply trying to keep their mate upright.

Janusz and Justyna shared a look and walked on. No one would describe Poles as abstemious, but any serious drinking was done at home and public drunkenness was frowned upon. Janusz’s mother, who’d visited London as a child before the war, had always spoken approvingly of the English as a decorous and reserved people, so it was fair to say that his first Friday night out with the guys from the building site had been something of an eye-opener. Still, the greatest compliment you could pay a man back then was to say he could carry his drink, and those who ended the night by falling over or picking a fight were viewed with pitying scorn.

Justyna shared a flat in a tidy-looking low-rise estate run by a housing association. Pausing on the pavement outside, she turned to him, drawing smoke from her cigarette deep into her lungs against the cold. ‘Thanks for the drinks,’ she said.

‘You’re welcome.’ He took a draw on his cigar, then exhaled, blowing his smoke downwind of her. She seemed in no hurry to go in.

‘Look, I really shouldn’t do this,’ she said at last. ‘I promised Nika …’

She pulled a folded slip of paper out of her pocket, and handed it to him.

‘Pawel made her swear not to give their address to anyone. But she wanted me to look out for letters from her mama, forward them on. She knew she could trust me,’ she stared off down the darkened street, ‘… thought she could trust me.’

He glanced at the paper, registering an address in Essex before pocketing it. ‘Listen, Justyna. You are the best friend Weronika has.’ He sought her gaze. ‘She’s probably found out by now that Pawel is no knight in shining armour – maybe she’s wondering how to leave him without too much fuss,’ he said, flexing his knuckles. ‘If that’s how it is, I’ll make sure her wishes are respected.’

She took a step toward him. ‘Be careful,’ she said, in a low voice. ‘I don’t think Pawel is right in the head. Nika must have let slip that I warned her off him, because one day he followed me home, all the way from work,’ her eyes widened. ‘He grabbed me by the arm and went crazy.’ Her lips trembled as she relived the shock of it. ‘He told me if I didn’t keep my fucking nose out, he’d kill me.’

The guy was clearly a psychol, thought Janusz. ‘Don’t worry,’ he told the girl. ‘Guys like him are usually all talk.’

She nodded, not entirely convinced. ‘And Nika said she’d phone me, but I’ve heard nothing, not even a text.’

A child cried sharply somewhere in her block and she shivered, then said in a rush: ‘It’s freezing – can I make you a coffee? Or maybe you’d like a wodka?’

That was unexpected. He sensed a fear of rejection in her averted face. Was she propositioning him? Compassion, good sense – and yes, temptation, too – wrestled briefly in his heart, and then a vision loomed up before him – the stern face of that old killjoy Father Pietruski.

He shook his head. ‘Another time, darling, I’ve got a lot on tomorrow.’

‘You’ll let me know when you find out where Nika is?’ said the girl, anxiety ridging her forehead.

‘You’ll be the first to hear,’ he said.

He watched her walk into the block, and two or three minutes later a first-floor light came on in what he guessed was her flat. He lingered, thinking that she might appear in the window, but was then distracted by the screech of a big dark-coloured car pulling out from the estate. Gunning its engine, it tore off down the street. When he looked back up at the block, the curtains had been closed on the oblong of light. Feeling a pang of loneliness, he threw down his cigar stub and left.

Eight

For DC Kershaw, the following day would turn out to be what her Dad might have called a game of two halves.

As she stretched herself awake in the pre-dawn gloom, her triceps and calf muscles delivered a sharp reminder of how she’d spent the previous evening – scaling the toughest route on the indoor wall on Mile End Road, handhold by punishing handhold. It was worth it, though. Climbing demanded a level of concentration so focused and crystalline that it left no headspace for stressing about the job. And she was getting pretty good, too – last summer she’d ticked off her first grade 7a climb, up in the Peaks. She hadn’t been tempted to mention her feat at work, obviously, because that would mean the entire nick calling her Spiderwoman … like for ever.

Still half-asleep, she stepped under the power shower, and found herself assaulted by jets of icy water. Gasping, she flattened her back against the cold glass and spun the knob right round to red, but it didn’t make a blind bit of difference. A quick tour of the flat revealed all the radiators to be stone cold, too – the boiler must be up the spout. Cursing, she pulled on her clothes, then her winter coat, and hurrying into the minuscule galley kitchen, turned on all four gas rings.

While she was scaling K2 last night, the rest of the guys had gone out on a piss-up to celebrate Browning’s birthday. She’d almost joined them, but luckily Ben Crowther tipped her off – with a look that said it definitely wasn’t his thing – that the birthday boy wanted to hit a lap-dancing club in Shoreditch later. No thanks. Being ‘one of the guys’ in the office was one thing, but she could live without the sight of Browning getting his crotch polished by some single mum with 36DD implants and a Hollywood wax.

The milk she added to her brewed tea floated straight to the surface in yellowy curds. Bugger. After making a fresh cup, black this time, she took it into the living room. As she sat on the sofa in her coat drinking the tea – too astringent-tasting without the milk – she fretted about how she would find time today to hassle the letting agents, let alone wangle a half-day off for the boiler repairman. Life had been a lot less stressful when Mark had lived here. Not that he was some spanner-wielding DIY god – Mark drove a desk in a Docklands estate agents and the only gadgets he’d mastered were the remote controls for the telly and the Skyplusbox – but it was so much easier when there were two of you to sort out the tedious household stuff.

As she attacked her last surviving nail, unshakeable habit and source of much mickey-taking at the station, her gaze fell on the dusty surface of the TV cabinet and the darker rectangle where the plasma screen used to sit. She’d let Mark take it when they split up last month.

How did I get to be sitting alone in a rented flat that I can’t afford, drinking black tea in my coat? she thought suddenly, and felt her eyes prickle.

She reminded herself how unbearable the atmosphere between her and Mark had become in those last few weeks, when their dead relationship lay in the flat like a decomposing body which they stepped over and around without ever acknowledging. By comparison, the previous phase had been preferable. The rows had started a couple of months ago, after she got the job at Newham CID and started coming home late and lagered-up two or three times a week. If she was in luck, he’d be asleep when she crawled into bed beside him, but if not, there’d be trouble. He’d complain she reeked of booze and fags, but they both knew that wasn’t the real issue. Mark never really accepted her argument that she went drinking with the guys not because she fancied any of them, but because bonding was fundamental to the job. The argument would get more and more heated, and then he’d start in on her language. Since you joined the cops, Nat, you talk more like a bloke than a bird.

The last accusation hit home; but you couldn’t spend all day holding your own with a bunch of macho guys, then come home and morph into Cheryl Cole. Sometimes she felt like she’d actually grown a Y-chromosome over the last few years.

Kershaw had always felt comfortable around men – probably because she’d been brought up by her father. The photos of her as a kid said it all – playing five-a-side with him and his mates in the park … holding up her first fish – a carp – caught at Walthamstow Reservoir … draped in a Hammers scarf on the way to the footie. Dad told her, more than once, that he never missed having a son, because with her he got the best of both worlds – a beautiful, clever little girl who could clear a pool table in under ten minutes.

Two years ago, when they told him the cancer was terminal, he confided, in a hoarse whisper that tore her heart out, that looking back, he had one regret: I should have remarried after your Mum died, he said, so you had someone to teach you how to be a lady.

Checking her watch, Kershaw gave a very unladylike sniff, wiped her face, and told herself to stop being such a wuss. Then, gulping the rest of the lukewarm tea down with a grimace, she picked up her bag.

As she closed the front door behind her, she heard her dad’s voice.

Up and at ’em, girl, it said, up and at ’em.

Parking in the minuscule car park attached to Newham nick was the usual struggle, and it didn’t improve Kershaw’s mood to see Browning’s car was already there. The little creep always got in early for his shift.

There was an email from Waterhouse in her inbox. The PM report had come back, and even better, the lab must have had a quiet week because they’d already done the tox report on DB16. It confirmed the cause of death as overdose by PMA – the dodgy drug Waterhouse had mentioned. Yes! She printed out the report, and surfing a wave of adrenaline, made a beeline for Streaky’s desk.

Later on, she would reflect it might have been better to wait till Streaky had downed his first pint of brick-red tea before she started waving the report around.

He didn’t lift his gaze from the racing pages. ‘Sarge …’ she tried, hovering over him, ‘Sorry to …’

‘Fuck off, I’m busy,’ he replied, without looking up.

‘The PM report on the floater …’

He lowered the paper, and fixed her with a bloodshot stare.

‘Which part of the well-known Anglo-Saxon phrase, “fuck off” don’t you understand? Go and wax your bikini line or something.’

With that he swivelled his chair to turn his back on her and circled a horse in the 2.30 p.m. at Newmarket. Face radiating heat, she slipped the report into his in-tray, and returned to her desk by the window. Browning, whose desk faced hers, caught her eye, his face a study in faux-sympathy.

‘Hangover,’ he hissed, leaning across the desk. ‘It turned into a bit of bender last night.’

‘Oh yes?’ said Kershaw, opening her mailbox.

‘You should have come,’ he said. ‘We had a good laugh at Obsessions – you know, the lap dance place?’

Suddenly, he started tapping on his keyboard. Glancing over her shoulder, Kershaw saw DI Bellwether standing behind them, deep in conversation with the Sarge.

Bellwether, a tall, fit-looking guy in his early thirties, was all matey smiles, although it was clear from his body language who was boss. Streaky had put on his jacket and adopted the glassy smile he employed with authority. Kershaw could tell he resented the Guv – not because the guy had ever done anything to him, but probably because Bellwether had joined the Met as a graduate on the now-defunct accelerated promotion programme, which meant he’d gained DI rank in five years, around half the time it would have taken him to work his way up in the old days. The very mention of accelerated promotion or, as he preferred to call it, arse-elevated promotion, would turn Streaky fire-tender red.

Kershaw thought his animosity toward Bellwether was all a bit daft, really, since Streaky was a self-declared career DS without the remotest interest in promotion. As he never tired of explaining, becoming an inspector meant kissing goodbye to paid overtime, spending more time on ‘management bollocks’ than proper police work, and having to count paperclips to keep the boss-wallahs upstairs happy. An absolute mug’s game, in other words.

She could overhear the two of them discussing the latest initiative from the Justice Department.

‘We’ll make it top priority, Guv,’ she heard Streaky say. He was always on his best behaviour with the bosses, and never uttered a word against any of them personally – a self-imposed discipline that no doubt dated from his stint as an NCO in the army.

As Bellwether breezed over, she and Browning got to their feet – Kershaw pleased that she’d chosen her good shoes and newest suit this morning.

‘Morning Natalie, Tom. Are you early birds enjoying the dawn chorus this week?’

Ha-ha, thought Kershaw, while Browning cracked up at the non-witticism.

‘What are you working on, Natalie?’ Bellwether asked her, with what sounded like real interest, causing Browning’s doggy grin to sag.

‘I’m on a floater, Guv, Polish female taken out of the river near the Barrier.’

‘Cause of death?’

‘OD. Some dodgy pseudo-ecstasy called PMA – might be coming over from Europe.’

‘PMA? That rings a bell …’ mused Bellwether. ‘Let me surf my inbox and give you a heads-up later today.’

Kershaw stifled a grin. Bellwether was alright, but attending too many management workshops had given him a nasty dose of jargonitis.

After he left, Streaky called her over.

‘So let me guess,’ he drawled, flipping through Waterhouse’s PM report. ‘The good doctor has got you all overexcited about a dodgy drugs racket. You do know he’s a tenner short of the full cash register?’

‘The tox report backs it up, though, Sarge,’ said Kershaw, keeping her voice nice and low. He had once informed the whole office that women’s voices were on the same frequency as the sound of nails scraped down a blackboard. Scientific fact, he said.

Streaky just grunted. ‘So you’ve got an OD with this stuff, wassitcalled … PMT …’ – no fucking way was she taking that bait – ‘but even assuming you had a nice juicy lead to the lowlife who supplied the drugs, what’s your possible charge?’

Keeping her voice nice and steady, Kershaw said, ‘Well, Sarge, it could be manslaughter …’

Streaky whistled. ‘Manslaughter. We are thinking big, aren’t we?’

‘Supplying a class-A drug to someone which ends up killing them is surely a pretty clear-cut case, Sarge.’ As soon as the words left her mouth she realised how up herself they made her sound.

Streaky leaned back in his swivel chair and put his arms behind his head.

‘Ah yes,’ he said, ‘I remember my early days as a dewy-eyed young Detective Constable …’

Here we go, she thought.

‘It was all so simple. Wielding the warrant card of truth and the truncheon of justice, I would catch all the nasty villains fair and square, put them in the dock, and Rumpole of the Bailey would send them away for a nice long stretch. End of.’

She resisted the urge to remind him that actually, Rumpole had been on the dark side, aka defence counsel.

‘Then I woke up,’ he yawned, ‘and found myself back in CID.’ He leaned forward and waved the PM report under her nose. ‘Even if you did find the dealer – which you won’t – and prove he supplied the gear – which you can’t – I can assure you that our esteemed colleagues at CPS will trot out 101 cast-iron reasons why it is nigh-on impossible to get a manslaughter conviction in cases of OD. The main one being it’s “too difficult to establish a chain of fucking causality”, if memory serves.’

He scooted the report into his pending tray with a flourish.

‘I’ll tell those long-haired tossers in Drug Squad about it. They might be interested if there are some killer Smarties doing the rounds. You carry on trying to trace the floater, just don’t spend all your time on it.’