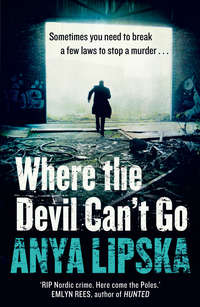

Where the Devil Can’t Go

‘Yes, Sarge.’ She hesitated, ‘But I still think that whoever gave the female the PMA – maybe her boyfriend, this guy Pawel – panicked and dumped her in the river after she OD-ed. I mean why else would she be starkers?’

She tensed up, half-expecting him to go ballistic at that; instead, he sighed, and picking up the report again with exaggerated patience, flicked through to the page he was looking for and started reading out loud.

‘The levels of PMA found in the blood may have caused hallucinations’ – he shot her a meaningful look – ‘… the subject’s core temperature would have risen rapidly, causing extreme discomfort …’ – his voice was getting louder and angrier by the second – ‘PMA overdose victims often try to cool off by removing clothing, wrapping themselves in wet towels and taking cold showers …’ He slapped the report shut. ‘Or maybe, Detective, seeing as they are off their tits, by jumping in the fucking river!’

Kershaw noticed that Streaky’s chin had gone the colour of raw steak, which was a bad sign. Now he picked a document out of his in-tray and shoved it at her.

‘Here you go, Miss Marple, the perfect case for a detective with a special interest in pharmaceuticals – a suspected cannabis factory in Leyton. Enjoy!’

Three hours later, Kershaw was shivering in her car, outside the dope factory, with the engine running in a desperate bid to warm up, smoking a fag and trying to remember why she ever joined the cops.

Thank God that ponytailed, earring-wearing careers teacher from Poplar High School couldn’t see her now. When she’d announced, aged sixteen, that she wanted to be a detective, he’d barely been able to hide his disapproval. He clearly had no time for the police, but could hardly say so. Instead, he adopted a caring face, and gave her a lecture on how ‘challenging’ she’d find police culture as a woman. She’d responded: ‘But sir, isn’t the only way to change sexist institutions from the inside?’

In truth, the police service hadn’t been her first career choice. As a kid, when her friends came to play, she’d inveigle them into staging imaginary court cases, with the kitchen of the flat standing in for the Old Bailey. Turned on its side, the kitchen table made a convincing dock for the defendant, while the judge, wearing a red dressing gown and a tea towel for a wig, oversaw proceedings perched up on the worktop. But the real star of the show was Natalie, who, striding about in her Nan’s best black velvet coat, conducted devastating cross-examinations and made impassioned speeches to the jury – aka Denzil, the family dog. As far as she could recall, she was always the prosecutor, never the defence. It wasn’t till she reached her teens that it dawned on her: the barristers in TV dramas always had names like Rupert or Jocasta, and talked like someone had wired their jaws together. The Met might be a man’s world, but at least coming from Canning Town didn’t stop you reaching the top.

The dope factory was in an ordinary terraced house in Markham Road, a quiet street, despite its closeness to Leyton’s scruffy and menacing main thoroughfare. Driving through, she had counted three lowlifes flaunting their gangsta dogs, vicious bundles of muscle, probable illegal breeds, trained to intimidate and attack. Obviously, she’d stopped to pull the owners over for a chat. Yeah, right.

The report said that the young Chinese men who had rented number 49 for four or five months hadn’t aroused any suspicions among the neighbours. Kershaw suspected that in a nicer area, their comings and goings at all hours, never mind the blackout blinds and rivers of condensation running down the inside of the windows, might have got curtains twitching a lot sooner, but then round here, maybe you were grateful if the place next door wasn’t actually a full-on crack house. In the end, number 49 had only got busted by accident, when a fire broke out on the ground floor.

As she pulled up, the fire tender was just driving off, leaving the three-storey house still smoking, the glass in the ground-floor windows blackened and cracked but otherwise intact. It looked like they’d caught the blaze early. Inside the stinking hallway, its elaborate cornice streaked with black, she picked her way around pools of sooty water, now regretting the decision to wear her favourite shoes. In the front room, once the cosy front parlour of some respectable Victorian family, she found a mini-rainforest of skunk plants, battered and sodden from the firemen’s hoses. Overhead, there hung festoons of wiring that had powered the industrial fluorescent strip lights; on the floor, a tangle of rubber tubing that presumably supplied the plants with water and the skunk-equivalent of Baby Bio.

‘Hello, beautiful, come to see what real cops do for a change?’

Frowning, she turned round, to find a familiar face – Gary, an old buddy from her time at Romford Road nick a few years back.

‘Gaz! How’s life on the frontline?’

Gary was a few years older than her – well into his thirties by now – and still a PC. He had been her minder when she had first gone on the beat as a probie, but they became proper mates after a memorable evening when they got called to a pub fight between football hoolies. West Ham had just thrashed old enemies Millwall at Upton Park, so it was the kind of ruck that could easily have become a riot. She and Gary could hardly nick them all: instead, they ID-ed the ringleaders and pulled them out, putting the lid on it without even getting their sticks out. Back at the station, Gary had told anyone who’d listen that Kershaw had thrown herself into the fray ‘just like a geezer’.

‘All the other rooms like this?’ she asked, after they’d done a bit of catching up.

‘Yep. Third one this month,’ said Gary, shaking his head. ‘You missed the best bit, though.’

Apparently, when he’d arrived on scene, he’d found a bunch of locals having an impromptu party outside the burning house.

‘It was quite a sight – there was a boom box blaring, they were drinking beer, dancing around in the smoke, everyone getting off their face on the free ganja,’ said Gary, shaking his head, grinning. ‘It was like Notting Hill Carnival.’

Kershaw smiled but her eyes were uneasy. Gary was probably the least racist cop she’d ever met, but she hoped he watched himself in front of the Guvnors. That sort of chat could get you into big trouble these days.

‘Down to us to do the clear-up, I suppose?’ she asked.

‘Got it in one, Detective,’ he grinned.

Kershaw spent the next few hours cursing the Sarge for dumping this nightmare job in her lap. The cheeky slags who ran the factory had powered it for free, running a cable from the lamppost next to their garden wall, which meant she had to call out the Electricity Board. She took half a dozen statements from the neighbours – total waste of time, of course, but she’d still have to type them up – and the worst job was still to come. Kershaw, Gary, and a single probie would have to bag and label every single one of the 1000-plus plants and load them onto a lorry to go to the evidence store.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов