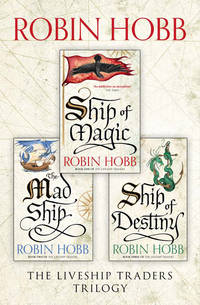

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

But as she walked down the docks, her confidence peeled away from her. How was she to employ such knowledge to feed herself? How could she approach any ship’s captain or mate, dressed as she was, and convince him that she was an able-bodied sailor? While female sailors were not rare in Bingtown, they were not all that common either. One frequently saw women working the decks of Six Duchies ships when they came to Bingtown. Many of the Three-Ships’ Immigrants had become fisherfolk, and among them, family ships were worked by the whole family. So while female sailors were not unknown in Bingtown, she’d be expected to prove herself just as tough or tougher than the men she’d have to work alongside. But she wouldn’t even be given the chance to try, dressed as she was. As the rising heat of the day made her uncomfortably aware of the weight and breadth of her dark skirts and modest jacket, she longed more and more for simple canvas trousers and a cotton shirt and vest.

Finally she stood beside Vivacia. She glanced up at the figurehead. To anyone else, it would have appeared that the ship was dozing in the sun. Althea did not even need to touch her to know that in actuality, the ship’s senses and thoughts were turned inward, keeping track of her own unloading. That job was proceeding apace, with longshoremen streaming down her gangplanks burdened with the variety of her cargo like ants fleeing a disturbed nest. They paid scant attention to her; Althea was just another gawker on the docks. She ventured closer to Vivacia and set a hand to her sun-warmed planking. ‘Hello,’ she said softly.

‘Althea.’ The ship’s voice was a warm contralto. She opened her eyes and smiled down at Althea. Vivacia extended a hand towards her, but lightened as she was, she floated too high for their hands to reach. Althea had to content herself with the sensations she received through the rough planking her hand rested on. Already her ship had a much greater sense of self. She could speak to Althea, and still keep awareness of cargo as it was shifted in her holds. And, Althea realized with a pang, she focused much of her awareness on Wintrow. The boy was in the chain locker, coiling and stowing lines. The heat of the tiny enclosed room was oppressive, while the thick ship’s smell all around him made him nauseated. The distress he felt had spread through the ship as a tension in the planking and a stiffness to the spars. Here, tied to the dock, that was not so bad, but out in the open sea a ship had to be able to give with the pressures of the water and wind.

‘He’ll be all right,’ Althea told Vivacia comfortingly, despite the jealousy she felt over the ship’s concern. ‘It’s a hard and boring task for a green hand, but he’ll survive it. Try not to think of his discomfort right now.’

‘It’s worse than that,’ the ship confided quietly. ‘He’s all but a prisoner here. He doesn’t want to be aboard, he wants to be a priest. We started out to be such wonderful friends, and now I think they are making him hate me.’

‘No one could hate you,’ Althea assured her, and tried to make her words sound confident. ‘He does want to be somewhere else; there’s no use in my lying to you about that. So what he hates is not being where he wants to be. He couldn’t possibly hate you.’ Steeling herself, as if she plunged her hand into fire, she added, ‘You can be his strength, you know. Let him know how much you value him, and what a comfort it is to you that he is aboard. As you once did for me.’ Try as she might, she could not keep her voice from breaking on the last words.

‘But I am a ship, not your child,’ Vivacia replied to Althea’s unvoiced thought rather than her words. ‘You are not giving up a little child with no knowledge of the world. I know in many ways I am naive still, but I have a wealth of memories and information to draw on. I just need to put them in some sort of order, and see how they relate to who I am now. I know you, Althea. I know you did not abandon me by choice. But you also know me. And you must understand how deeply it hurts me when Wintrow is forced to be aboard me, forced to be my companion and heart’s friend when he wishes he were elsewhere. We are drawn to one another, Wintrow and I. But his anger at the situation makes him resist that bond. And it makes me ashamed that I so often reach toward him.’

The division within the ship’s heart was terrible to feel. Vivacia battled her own need for Wintrow’s companionship, forcing herself to stand still in a cold isolation that was grey as fog. Almost Althea could sense it as a terrible place, rainswept and chill and endlessly grey. It appalled her. As Althea searched for comforting words, a man’s voice rang out loud and commanding over the ordinary dock yells and thuds. ‘You. You there! Get away from the ship! Captain’s orders, you aren’t to come aboard her.’

Althea tipped her head back, shielding her eyes against the sun’s glare. She stared up at Torg as if she had not recognized his voice. ‘This, sir, is a public dock,’ she pointed out calmly.

‘Well, this ain’t a public ship. So shove off!’

As little as two months ago, Althea would have exploded at him. But the time she had spent secluded with Vivacia and the events of the last three days had changed her. It was not that she was a better-tempered person, she decided detachedly. It was that her anger had learned a terrible patience. What good was wasting words on a petty and tyrannical second mate? He was a little yapping dog. She was a tigress. One did not waste snarls on such a creature. You waited until you could snap his spine with a single blow. He had sealed his fate with his mistreatment of Wintrow. His rudeness to Althea would be redeemed at the same time.

And with a wave of giddiness, Althea realized that while her hand rested on the planking, her thoughts were Vivacia’s and Vivacia’s were hers. Belatedly she pulled free of the ship, feeling as if she drew her hand out of cold, wrist-deep molasses. ‘No, Vivacia,’ Althea said quietly. ‘Do not let my anger become your own. And leave vengeance to me, do not soil yourself with it. You are too big, too beautiful; it is unworthy of you.’

‘He is unworthy of my deck, then,’ Vivacia replied in a low, bitter voice. ‘Why must I tolerate vermin like him while you are put ashore? You cannot tell me it is the Vestrit way to treat kinsmen so.’

‘No. No, it is not,’ Althea hastily assured her.

‘I said, move on,’ Torg shouted once more from the deck above her. Althea glanced up at him. He was leaning over the railing, shaking his fist at her. ‘Move along, or I’ll have you moved along!’

‘There’s really nothing he can do,’ Althea assured the ship. But even as she spoke, she heard a muffled cry and then a heavy thud from within Vivacia’s hold. Someone cursed fluently on the deck, followed by cries for Torg. A young sailor’s voice floated up clearly. ‘The hoist tackle’s pulled free of the beam, sir! I’d swear it was set sound enough when we started work.’

Torg’s head disappeared and Althea heard the sound of his feet running across the deck. The unloading of Vivacia’s cargo ground to a halt as half the crew came to gawk at the smashed pallet and crates and the scattered comfer nuts. ‘That should keep him busy for a time,’ Vivacia observed sweetly.

‘I do have to leave, though,’ Althea hastily decided. If she stayed, she would have to ask the ship if she had had anything to do with the fallen block-and-tackle. ‘Take care of yourself,’ she told Vivacia. ‘And look after Wintrow, too.’

‘Althea! Will you be back?’

‘Of course I will. There are just a few things I need to take care of. But I’ll be back to see you again before you sail.’

‘I can’t imagine sailing without you,’ Vivacia said desolately. The figurehead lifted her eyes to the distant horizon, as if she were already far beyond Bingtown. A stray breeze stirred the heavy locks of her hair.

‘It’s going to be hard to stand here on the docks and watch you go off into the distance. At least you’ll have Wintrow aboard.’

‘Who hates being with me.’ The ship abruptly sounded very young again. And very distressed.

‘Vivacia. You know I can’t stay here. But I will be back. Know that I am working on a way to be with you. It will take me some time, but I will be with you again. Until then, behave yourself.’

‘I suppose so,’ Vivacia sighed.

‘Good. I will see you again soon.’

Althea turned and hastened away. Her insincerity had nearly choked her. She wondered if the ship had been fooled at all. She hoped she had, and yet every instinct she had about Vivacia told her that she could not be tricked that easily. She must know how jealous Althea was of Wintrow’s place aboard her, she must be able to sense her deep, deep anger at how things had turned out. And yet Althea hoped she did not, hoped that Vivacia had had nothing to do with the fallen hoist, and prayed to Sa fervently that the ship would not attempt to right things on her own.

As she turned to go, she reflected that the ship was both like and unlike what she had expected. She had dreamed of a ship with all the good qualities of a proud and beautiful woman. She had not paused to think that Vivacia had inherited not just her father’s experience, but that of her grandfather and great-grandmother as well, to say nothing of what Althea herself had added. She feared now that the ship would be just as hammer-headed as any other Vestrit, just as slow to forgive, just as intent on having her own way. If I were aboard, I could guide her, as my father guided me through my stubborn times. Wintrow will not have the vaguest idea of how to deal with her. A tiny black thought pushed itself into her mind. If she kills Kyle, he will have brought it on himself.

A chill of disgust raced through her that she could even harbour such a thought. She stooped hastily, to rap her knuckles against the wood of the dock, to proof her fate against Vivacia ever doing anything so horrible. As she straightened up, she felt eyes on her. She lifted her gaze to find Amber standing, staring at her. The golden woman was dressed in a long simple robe the colour of a ripe acorn, and her hair was bound down her back in a single shining plait. The fabric of the robe fell in pleats from her shoulders to the hem, concealing every line of her body. Her hands were gloved, to conceal the scars and callouses of an artisan’s fingers in the guise of a gentlewoman’s hands. Amidst the hustle and bustle of the busy dock, she stood still, as unaffected by all of it as if she were enclosed in a glass bubble. For a second her tawny eyes locked with Althea’s, and Althea’s mouth went dry. There was something other-worldly about her. All around her, folk came and went on their business, but where she stood there was stillness and focus. She wore a necklace of simple wooden beads, gleaming in every tone of brown that wood could be. Even from where she stood, they caught Althea’s eyes and she felt drawn to them. She doubted that anyone could look at them and not desire to possess them.

Her eyes darted up to Amber’s face. Once more their eyes met. Amber did not smile. She slowly turned her head, first to one side and then to another as if inviting Althea to admire her profile. Instead Althea noticed only her mismatched earrings. She wore several in each ear, but the ones that drew Althea’s attention were the twisted serpent of gleaming wood in her left ear and the shining dragon in her right. Each was as long as a man’s thumb, and so cunningly carved she almost expected them to twitch with life. Althea suddenly realized how long she had been staring. Unwillingly she met Amber’s gaze again. The woman smiled questioningly at her. When Althea kept her own features perfectly still, the woman’s smile faded to a look of disdain. That expression did not change as she set a slender-fingered hand to her flat belly. As if those gloved fingers had touched her own midsection, Althea felt a chill dread spread throughout her. She glanced once more at Amber’s face; it looked set and purposeful now. She stared at Althea like an archer fixing his eye on his target. In all the hurrying, busy folk, they were abruptly alone, eyes locked, impervious to the crowd. With an effort as physical as pulling away from a grasping hand, Althea turned and fled up the docks, back towards Bingtown.

She hurried clumsily through the crowded summer market, bumping into folk, knocking against a table full of scarves when she turned to look back over her shoulder. There was no sign of Amber following her. She moved on more purposefully down the walk. Her pounding heart slowed and she became aware of how she was sweating in the afternoon sun. Her encounters with the ship and Amber had left her dry-mouthed and almost shaky. Silly. Ridiculous. All the woman had done was look at her. Where was the threat in that? She had never before been prone to such flights of fancy. Likely it was the stress of the last two days. And she could not recall when she had last eaten a decent meal. Come to think of it, other than beer, she had had almost nothing since the day before yesterday. That was most likely what was wrong with her.

She found a back table in a small streetfront tea shop, and sat down. She felt limply grateful to be out of the afternoon sun. When the boy came to the table, she ordered wine and smoked fish and melon. After he had bowed and gone, she belatedly wondered if she had enough coin to pay for it. When she had dressed so carefully that morning, she had not given any thought to such things. Her room at home was as immaculately tidy as it always was when she had returned to it after a sea voyage. There had been some coins and notes in the corner of her drawer; these she had scooped and stuffed in her pockets before she tied them on, more out of habit than anything else. Even if there was enough to pay for this simple meal, there was certainly not enough to pay for an inn room somewhere. Unless she wanted to go crawling home with her tail between her legs, she’d better think of what she actually planned to do to get by.

While she was still wrestling with that, the food came. She recklessly called for wax and pressed her signet ring into a blotch on a tally stick. Probably the last time she’d get away with sending the bill to her father’s house. If she’d thought of that, she would have let Keffria buy her a more elegant meal. But the melon was crisp and sweet, the fish moistly smoked and the wine was, well, drinkable. She had had worse before and would no doubt have worse again. She just had to persevere and things would get better with time. Things had to get better.

As she was finishing her wine, it came to her in a sudden rush that her father was still dead, and he was going to be dead for the rest of her life. That part of her life was never going to get better. She had almost become accustomed to her grief; this new sense of deep loss jellied her legs. No matter how long she managed to hang on, Ephron Vestrit wasn’t going to come home and straighten it all out. No one was going to make it all right unless she did it herself. She doubted Keffria’s ability to manage the family fortunes. Keffria and her mother might have handled things well enough, but Kyle was going to be stirring the pot, too. Leaving herself entirely out of the picture, how bad could things get for the Vestrits?

They could lose everything.

Even Vivacia.

It had never quite happened yet in Bingtown, but the Devouchet family had come close. They had sunk themselves so deeply in debt that the Traders’ Council had agreed that their main creditors, Traders Conry and Risch, could take possession of the Devouchet liveship. The eldest son was to have remained aboard the ship as an indentured servant to them until the family debts were paid, but before the settlement had been finalized, that same son had brought the ship into port at Bingtown with a cargo rich enough to satisfy their creditors. The whole town had rejoiced in his triumph, and for a time he had been a sort of hero. Somehow Althea could not see Kyle in that role. No. More likely he would surrender both ship and son to his creditors, and tell Wintrow it was his fault.

With a sigh, she forced her mind back to that which she feared most. What was happening to Vivacia? The ship was but newly quickened; liveship lore claimed that her personality would develop over the next few weeks. All agreed there was really no predicting what temperament a ship might have. A ship might be markedly like its owners, or amazingly different. Althea had glimpsed a ruthlessness in Vivacia that chilled her. In the weeks to come, would that trait become more marked, or would the ship suddenly evince her father’s sense of justice and fair-play?

Althea thought of Kendry, a notoriously wilful ship. He would not tolerate live cargo in his hold and he hated ice. He’d sail south to Jamaillia willingly enough, but sailors declared that working his decks on a trip north to Six Duchies or beyond was like sailing a leaden ship. On the other hand, given a fragrant cargo and a southern destination, the ship would fair sail himself, swift as the wind. So a strong will in a ship was not so terrible a thing.

Unless the ship went mad.

Althea poked at the last bit of fish on her plate. Despite the warmth of the summer day, she felt cold inside. No. Vivacia would never become like Paragon. She could not. She was properly quickened, with ceremony and welcome, after three full lifetimes of sailing had been put into her. All knew that was what ruined Paragon. The greed of the owners had created a mad liveship, and brought death and destruction on their family line.

The Paragon had had but one lifetime when Uto Ludluck assumed command. All said that Uto’s father Palwick had been a fine Trader and a great captain. Of Uto, the kindest thing that could be said was that he was shrewd and cunning. And willing to gamble. Anxious to pay off the liveship in his lifetime, he had sailed the Paragon always overloaded. Few sailors cared to ship aboard him twice, for Uto was a harsh taskmaster, not only with his underlings but with his young son Kerr, the ship’s boy. There were rumours that the unquickened ship was difficult to handle, though most blamed it on too much canvas and too little free board due to Uto’s greed.

The inevitable happened. There came a winter day in the storm season when the Paragon was reported as overdue. Setre Ludluck haunted the docks, asking word of every ship that came in, but no one had seen the Paragon or had word of her husband and son.

Six months later, the Paragon came home. He was found floating in the mouth of the harbour, keel up. At first no one knew who the derelict was; only that from the silver wood it was a liveship. Volunteers in dories towed the ship into the beach and anchored it there until a low tide could ground it and reveal the disastrous news it bore. When the retreating waters ebbed away, there lay the Paragon. His masts had been sheared away from the ferocity of some killer storm, but the hardest truth was on his deck. Lashed so securely to his deck that no storm or wave could loose it were the remains of his final cargo. And tangled in the cargo net were the fish-eaten remains of Uto Ludluck and his son Kerr. The Paragon had brought them home.

But perhaps most horrible of all was that the ship had quickened. The deaths of Uto and Kerr had finished out the count of three lives ended aboard him. As the water slipped away to bare the figurehead, the bearded countenance of the fiercely carved warrior cried out aloud in a boy’s voice, ‘Mother! Mother, I’ve come home!’

Setre Ludluck had shrieked and then fainted. She was borne away home, and refused ever after to visit the sea wall in the harbour where the righted Paragon was eventually docked. The bereft and frightened ship was inconsolable, sobbing and calling for days. At first folk were sympathetic and made efforts to comfort him. Kendry was tied up near him for close to a week, to see if the older ship could not soothe him. Instead Kendry became agitated and difficult and eventually had to be moved. And Paragon wept on. There was something infinitely terrible in that fierce, bearded warrior with the muscled arms and hairy chest, who sobbed like a frightened child and begged for his mother. From sympathy, folk’s hearts turned to fear, and finally a sort of anger. It was then that Paragon earned a new name for himself: Pariah, the outcast. No ship’s crew wanted to tie up alongside him; bad luck, sailors nodded to one another, and left him to himself. The ropes that bound him to the docks grew soft with rot and heavy with barnacles. Paragon himself grew silent, save for unpredictable outbursts of savage cursing and wailing.

When Setre Ludluck died young, ownership of Paragon passed to the family’s creditors. To them he was but a stone about their necks, a ship that could not be sailed, taking up an expensive slip in the harbour. In time, several cousins were grudgingly offered a part ownership in the vessel if they could induce the ship to sail. Two brothers, Cable and Sedge came forward to claim the ship. The competition was fierce, but Cable was the elder by a few minutes. He claimed the prize and vowed he would reclaim the family’s liveship. He spent months talking to Paragon, and eventually seemed to have a sort of bond with him. To others he said the ship was like a frightened child who responded best to coaxing. Those who held the family’s debt on the liveship extended Cable credit, muttering somewhat about sending good money after bad, but unable to resist the hope that they might recoup their losses. Cable hired crew and workmen, paying outrageous wages simply to get sailors to approach the inauspicious ship. It took the better part of a year for him to have Paragon refitted and to hire a full crew to sail him. He was roundly congratulated on having salvaged the ship, for in the days before he sailed, Paragon became known as a bashful but courteous ship, given to few words but occasionally smiling so as to melt anyone’s heart. On a bright spring day, they left Bingtown. Cable and his crew were never heard from again.

When next Paragon was sighted, he was a wreck of shattered and dangling rigging and tattered canvas. Reports of him reached Bingtown months before he did. He rode low in the water, his decks nearly awash, and no human replied to the hails of other passing ships. Only the figurehead, black-eyed and stone-faced, stared back at those who ventured close enough to see for themselves that no one worked his decks. Back to Bingtown he came, back to the sea wall where he had been tied for so many years. The first and only words he was reputed to have spoken were, ‘Tell my mother I’ve come home.’ Whether that was truth or the stuff of legend, Althea could only guess. When Sedge had been bold enough to tie up the ship and go aboard, he found no trace of his brother or of any sailor, living or dead. The last entry in the log spoke of fine weather, and the prospect of a good profit on their cargo. Nothing indicated a reason why the crew would have abandoned the ship. In his hold had been a waterlogged cargo of silks and brandy. The creditors had claimed what was salvageable, and left the ship of ill omen to Sedge. All the town had thought the man was mad when he claimed Paragon, and took notes on his house and lands to refit him.

Sedge had made seventeen successful voyages with Paragon. To those who asked how he had managed it, he replied that he ignored the figurehead, and sailed the ship as if it were no more than wood. For those years, Paragon’s figurehead was indeed a mute thing, glaring balefully on any who glanced his way. His powerful arms were crossed on his muscled chest, his jaws clamped as tightly shut as they had been when he was wood. Whatever secret the ship knew about the fates of Cable and his crew, he kept them to himself. Althea’s father had told her that Paragon had been almost accepted in the harbour; that some said that Sedge had broken the string of ill luck that had haunted the ship. Sedge himself bragged of his mastery of the liveship, and fearlessly took his eldest son off to sea with him. Sedge redeemed the note on his house and lands and made a comfortable living for his wife and children. Some of the ship’s former creditors began to mumble that they had acted too hastily in signing the ill-omened ship back to him.