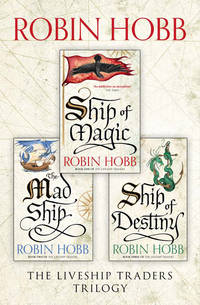

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

But Paragon never returned from Sedge’s eighteenth voyage. It was a bad year for storms, and some said that Sedge’s fate was no different from what many a mariner suffered that year. Heavily-iced rigging can overturn any ship, live or no. Sedge’s widow walked the docks and watched the horizon with empty eyes. But it was a full twenty years, and she had remarried and borne more children before Paragon returned.

Once more he came floating hull up, defying wind and tide and current to drift slowly home. This time when the silvery wood of his keel was sighted, folk knew almost at once who he was. There were no volunteers to tow him in, no one was interested in righting him or finding out what had become of his crew. Even to speak of him was deemed ill luck. But when his mast stuck fast in the greasy mud of the harbour and his hulk became a hazard to every ship that came and went, the harbourmaster ordered his men out. With curses and sweat they dragged him free, and on the highest tide of that month, they winched him as far ashore as they could. The retreating tides left him completely aground. All could see then that it was not just the crew of Paragon that had suffered a harsh fate. For the figurehead itself was mutilated, hacked savagely with hatchet bites between brow and nose. Of the ship’s dark and brooding glance, nothing remained but splintered wood. A peculiar star with seven points, livid as a burn scar, marred his chest. It was all the more terrible that his mouth scowled and cursed as savagely as ever, and that the groping hands reached out, promising to rend whoever came in reach of them. Those bold enough to venture aboard told of a ship stripped to its bare bones. Nothing remained of the men who had sailed him, not a shoe, not a knife, nothing. Even his log books were gone, and deprived of all his memories, the liveship muttered and laughed and cursed to himself, all sense run out of his words like sand out of a shattered hourglass.

So Paragon had remained for all of Althea’s lifetime. The Pariah or Goner, as he was sometimes referred to, was occasionally almost floated by an exceptionally high tide, but the harbourmaster had ordered him well anchored to the beach cliffs. He would not allow the hulk to break free and wash out to sea where he might become a hazard to other ships. Nominally, Pariah was the property of Amis Ludluck now, but Althea doubted she had ever visited the beached wreckage of the liveship. Like any other mad relative, he was kept in obscurity, spoken of in whispers if spoken of at all. Althea imagined such a fate befalling Vivacia and shuddered.

‘More wine?’ the serving boy asked pointedly. Althea shook her head hastily, realizing she had lingered far too long at this table. Sitting here and mulling over other people’s tragedies was not going to make her own life any better. She needed to act. The first thing she should do was tell her mother just how troubled the liveship seemed to be and somehow convince her that Althea must be allowed back on board to sail with her. The second thing she would do, she decided, was to cut her own throat before she did anything that might appear as childish whining.

She left the tea shop and wandered the busy market streets. The more she tried to focus her mind on her problems, the more she could not decide which problem to confront first. She needed a place to sleep, food, a prospect of employment for herself. Her beloved ship was in insensitive hands, and she could do nothing to change it. She tried to think of allies she could depend on to help her and could come up with no one. She cursed herself now for not cultivating the company of other Traders’ sons and daughters. She had no beau she could turn to, no best friend who would shelter her for a few days. On board the Vivacia she had had her father for companionship and serious talk, and the sailors for company and joking. Her days in Bingtown had either been spent at home, revelling in the luxury of a real bed and hot meals of fresh food, or following her father about on business errands. She knew Curtil his advisor, and several money-changers, and a number of merchants who had bought cargo from them over the years. Not one of them was someone she could turn to in her present difficulties.

Nor could she go home without appearing to crawl. And there was no predicting what Kyle would attempt to do if she appeared on the doorstep, even to claim her things. She wouldn’t put it past him to try and lock her up in her room like a naughty child. Yet she had a responsibility to Vivacia that didn’t stop even if they had declared the ship no longer belonged to her.

She finally salved her conscience by stopping a message runner. For a penny, she got a sheet of coarse paper and a charcoal pencil and the promise of delivery before sundown. She penned a hasty note to her mother, but could find little more to say except that she was concerned for the ship, that Vivacia seemed unhappy and restless. She asked for nothing for herself, only that her mother would visit Vivacia herself and encourage the ship to speak plainly to her and reveal the source of her unhappiness. Knowing it would be seen as overly dramatic, she nevertheless reminded her mother of Paragon’s sad fate, saying she hoped her family’s ship would never share it. Then Althea re-read her missive, frowning at how histrionic it seemed. She told herself it was the best she could do, and that her mother was the kind of person who would at least go down and see for herself. She sealed it with a dab of wax and an uneven press from her ring, and sent the lass on her way with it.

That much done, she lifted her head and looked around her. She had wandered into Rain Wild Street. It had always been a favourite section of town for her father and her. After they had conducted their business, they almost always found an excuse to stroll down it arm in arm, delighting in calling each other’s attention to new and exotic wares. The last time they had walked here together, they had spent almost an afternoon in a crystal shop. The merchant featured a new kind of wind chimes. The slightest breath stirred them to music, and they played, not randomly, but an elusive and endless tune, too delicate for mortal tongue to hum and lingering oddly in the mind afterward. He had bought her a little cloth bag full of candied violets and rose petals, and a set of earrings shaped like sailfish. She had helped him pick out some perfume gems for her mother’s birthday, and had gone with him to the silversmith to have them set in rings. It had been an extravagant day, of wandering in and out of the odd little shops that showcased the wares of the Rain River folk.

It was said that magic flowed with the waters of the Rain River. And certainly the wares that the Rain River families sent into town were marvellously tinged with it. Whatever dark rumours one might hear of those settlers who had chosen to remain in the first settlement on the Rain River, their trade goods reflected only wonder. From the Verga family came trade goods with the scent of antiquity on them: finely woven tapestries depicting folk not quite human, with eyes of lavender or topaz; bits of jewellery made of a metal whose source was unknown, in wondrously strange designs; lovely pottery vases, both aromatic and graceful. The Soffrons marketed pearls in deep shades of orange and amethyst and blue, and vessels of cold glass that never warmed and could be used to chill wine or fruit or sweet cream. From others came kwazi fruit, whose rind yielded an oil that could numb even a serious wound and whose pulp was an intoxicant with an effect that lingered for days. The toy shops always lured Althea the strongest: there one could find dolls whose liquid eyes and soft warm skin mimicked that of a real infant, and clockwork toys so finely geared they would run for hours, pillows stuffed with herbs that assured wonderful dreams, and marvellously carved smooth stone that glowed with a cool inner light to keep nightmares at bay. The prices on such things were dear, even in Bingtown, and extravagantly high once the goods had been shipped to other ports. Even so, price was not the reason why Ephron Vestrit refused to buy such toys, even for the outrageously spoiled grand-daughter Malta. When Althea had pressed him about it, he had only shaken his head. ‘You cannot touch magic and not carry away some of its taint upon you,’ he had told her darkly. ‘Our forebears judged the price too high, and left the Rain Wilds to settle Bingtown. And we ourselves do not traffic in Rain Wild goods.’ When she had pressed him as to what he meant, he had shaken his head and told her that they would discuss it when she was older. But even his misgivings had not stopped him from buying the perfume gems that his wife had so longed for.

When she was older.

Well, no matter how much older she got, that was a discussion they would never have. The bitterness of this broke her out of her pleasant memories and into the dwindling afternoon. She left the Rain Wild Street, but not without an apprehensive glance at Amber’s shop on the corner. She almost expected to spy the woman staring out of the window at her. Instead the window showed only her wares draped artfully on a spread of cloth-of-gold. The door to the shop stood invitingly open, and folk were coming and going. So her business prospered. Althea wondered which of the Rain River families she was allied with, and how she had managed it. Unlike most of the other stores, her street sign did not bear a Trader family insignia.

In a quiet alley, Althea untied her pockets and considered their contents. It was as she had expected. She could have a room and a meal tonight, or she could eat frugally for several days on what it held. She thought again of simply going home, but could not bring herself to do it. At least, not while Kyle might be there. Later, after he had sailed, if she had not found work and a place to stay by then, then she might be driven to go home and retrieve at least her clothes and personal jewellery. That much she surely could claim, without loss of pride. But not while Kyle was there. Absolutely not. She dumped the coins and notes into her purse and cinched it tight, wishing she could call back the money she had spent so carelessly on drink the night before. She couldn’t, so best to be careful with what remained. She hung the pockets back inside her skirts.

She left her alley and found herself walking purposefully down the street. She needed a place to stay for the night and there was but one that came to mind. She tried not to think of the many times her father had sternly warned her about his company before he finally outright forbade her to visit him. It had been months since she had last spoken to him, but when she was a child, before she began sailing with her father, she had spent many summer afternoons in his company. Although the other children from town had found him both alarming and disgusting, Althea had soon lost her fear of him. She had felt sorry for him, truth to be told. He was frightening, true, but the most frightening part about him was what others had done to him. Once she had grasped that, a tentative friendship had followed.

As the afternoon sun dimmed into a long summer’s evening, Althea left Bingtown proper behind her and began to pick her way down the rock-strewn beach to where Paragon reposed on the sand.

12 OF DERELICTS AND SLAVESHIPS

BELOW THE WATER. Not just for a breath, not engulfed in the moment of a wave, but hanging upside-down below the water, hair flowing with the movement of it, lungs pumping only saltwater. I am drowned and dead, he thought to himself. Drowned and dead as I was before. Before him was only the greenly-lit world of fishes and water. He opened his arms to it, let them dangle below his head and move with the waves. He waited to be dead.

But it was all a cheat, as it was always a cheat. All he wanted was to stop, to cease being, but it was never allowed him. Even here, beneath the water, his decks stilled of battering feet and shouted commands, his holds replete with seawater and silence, there was no peace. Boredom, yes, but no peace. The silver shoals of fish avoided him. They came toward him like phalanxes of sea-birds, only to veer away, still in formation, as they sensed the unholy wizardwood of his bones. He moved alone in a world of muted sounds and hazed colours, unbreathing, unsleeping.

Then the serpents came.

They were drawn to him, it seemed, both repulsed and fascinated by him. They taunted him, peering at him, their toothy maws opening and closing so close to his face and arms. He tried to push them away, but they mobbed him, letting his fists batter at them as frantically as he might, and never showing any sign that they felt his strength as anything greater than a fish’s helpless flopping. They spoke about him to one another, submerged trumpeting he almost understood. That was the most frightening thing, that he almost understood them. They looked deep into his eyes, they wrapped his hull in their sinuous embraces, holding him tight in a way that was both threatening and reminiscent of… something. It lurked around the last corner of his memory, some vestige of familiarity too frightening to summon to the forefront of his mind. They held him and dragged him down, deeper and deeper, so that the cargo still trapped inside him tore at him in its buoyant drive to be free. And all the while they accused and demanded furiously, as if their anger could force him to understand them.

‘Paragon?’

He startled awake, from a dream with vision into the eternal hell of darkness. He tried to open his eyes. Even after all the years, he still tried to open his eyes and see who addressed him. Self-consciously, he lowered his up-reaching arms, crossed them protectively over his scarred chest to conceal the shame there. He almost knew her voice. ‘Yes?’ he asked guardedly.

‘It’s me. Althea.’

‘Your father will be very angry if he finds you here. He will roar at you.’

‘That was a very long time ago, Paragon. I was just a girl then. I’ve come to see you a number of times since then. Don’t you remember?’

‘I suppose I do. You do not come often. And your father roaring at us when he found you here with me is what I remember best about you. He called me a “damnable piece of wreckage” and “the worst sort of luck one could have”.’

She sounded almost ashamed as she replied, ‘Yes. I remember that too, very clearly.’

‘Probably not as clearly as I. But then, you probably have a greater variety of memories to choose from.’ He added petulantly, ‘One does not gather many unique memories, hauled out on a beach.’

‘I am sure you had a great many adventures in your day,’ Althea offered.

‘Probably. It would be nice if I could remember any of them.’

He heard her come closer. From the shifting in the angle of her voice, he judged she had sat down on a rock on the beach. ‘You used to speak to me of things you remembered. When I was a little girl and came here, you told me all sorts of stories.’

‘Most of them were lies, I expect. I don’t remember. Or maybe I did then, but no longer do. I think I am getting vaguer. Brashen thinks it might be because my log is missing. He says I do not seem to recall as much of my past as I used to.’

‘Brashen?’ A sharp edge of surprise in her voice.

‘Another friend,’ Paragon replied carelessly. It pleased him to shock her with the news he had another friend. Sometimes it irritated him that they expected him to be so pleased to see them, as if they were the only people he knew. Though they were, they should not have been so confident of it, as if it were impossible a wreck such as he might have made other friends.

‘Oh.’ After a moment, Althea added, ‘I know him as well. He served on my father’s ship.’

‘Ah, yes. The… Vivacia. How is she? Has she quickened yet?’

‘Yes. Yes, she has. Just two days ago.’

‘Really? Then it surprises me you are here. I thought you would rather be with your own ship.’ He had had all the news from Brashen already, but it gave him an odd pleasure to force Althea to speak of it.

‘I suppose I would be, if I could,’ the girl admitted unwillingly. ‘I miss her so much. I need her so badly just now.’

Her honesty caught Paragon off-guard. He had accustomed himself to think of people as givers of pain. They could move about so freely and end their lives at any time they chose; it was hard for him to understand that she could feel such a depth of pain as her voice suggested. For a moment, somewhere in the labyrinths of his memory a homesick boy sobbed into his bunk. Paragon snatched his consciousness back from it. ‘Tell me about it,’ he suggested to Althea. He did not truly want to hear her woes, but at least it was a way to keep his own at bay.

It surprised him when she complied. She spoke long, of everything, from Kyle Haven’s betrayal of her family’s trust to her own incomplete grief for her father. As she spoke, he felt the last warmth of the afternoon ebb away and the coolness of night come on. At some time she left her rock to come and lean her back against the silvered planking of his hull. He suspected she did it for the warmth of the day that lingered in his bones, but with the nearness of her body came a greater sharing of her words and feelings. It was almost as if they were kin. Did she know that she reached toward him for understanding as if he were her own liveship? Probably not, he told himself harshly. It was probably just that he reminded her of Vivacia and so she extended her feelings into him. That was all. It was not especially intended for him.

Nothing was especially intended for him.

He forced himself to remember that, and so he could be calm when, after she had been silent for some time, she said, ‘I have no place to stay tonight. Could I sleep aboard?’

‘It’s probably a smelly mess in there,’ he cautioned her. ‘Oh, my hull is sound enough, still. But one can do little about storm waters, and blown sand and beach lice can find a way into anything.’

‘Please, Paragon. I won’t mind. I’m sure I can find a dry corner to curl up in.’

‘Very well, then,’ he conceded, and then hid his smile in his beard as he added, ‘if you don’t mind sharing space with Brashen. He comes back here every night, you know.’

‘He does?’ Startled dismay was in her voice.

‘He comes and stays almost every time he makes port here. It’s always the same. The first night it’s because it’s late and he’s drunk and he doesn’t want to pay a full night’s lodging for a few hours’ sleep and he feels safe here. And he always goes on about how he’s going to save his wages and only spend a bit of it this time, so that some day he’ll have enough saved up to make something of himself.’ Paragon paused, savouring Althea’s shocked silence. ‘He never does, of course. Every night he comes stumbling back, his pockets a bit lighter, until it’s all gone. And when he has no more to spend on drink, then he goes back and signs on whatever ship will have him until he ships out again.’

‘Paragon,’ Althea corrected him gently. ‘Brashen has worked the Vivacia for years now. I think he always used to sleep aboard her when he was in port here.’

‘Well, but, yes, I suppose so, but I meant before that. Before that, and now.’ Without meaning to, he spoke his next thought aloud. ‘Time runs together and gets tangled up, when one is blind and alone.’

‘I suppose it would.’ She leaned her head back against him and sighed deeply. ‘Well. I think I shall go in and find a place to curl up, before the light is gone completely.’

‘Before the light is gone,’ Paragon repeated slowly. ‘So. Not completely dark yet.’

‘No. You know how long evening lingers in summer. But it’s probably black as pitch inside, so don’t be alarmed if I go stumbling about.’ She paused awkwardly, then came to stand before him. Canted as he was on the sand, she could reach his hand easily. She patted it, then shook it. ‘Good night, Paragon. And thank you.’

‘Good night,’ he repeated. ‘Oh. Brashen has been sleeping in the captain’s quarters.’

‘Right. Thank you.’

She clambered awkwardly up his side. He heard the whisper of fabric, lots of it. It seemed to encumber her as she traversed his slanting deck and finally fumbled her way down into his cargo hold. She had been more agile as a girl. There had been a summer when she had come to see him nearly every day. Her home was somewhere on the hillside above him; she spoke of walking through the woods behind her home and then climbing down the cliffs to him. That summer she had known him well, playing all sorts of games inside him and around him, pretending he was her ship and she his captain, until word of it came to her father’s ears. He had followed her one day, and when he found her talking to the cursed ship, he soundly scolded them both and then herded Althea home with a switch. For a long time after that she had not come to see him. When she did come, it was only for brief visits in early dawn or evening. But for that one summer, she had known him well.

She still seemed to remember something of him, for she made her way through his interior until she came to the aft space where the crew used to hang their hammocks. Odd, how the feel of her inside him could stir such memories to life again. Crenshaw had had red hair and was always complaining about the food. He had died there, the hatchet that ended his life had left a deep scar in the planking as well, his blood had stained the wood…

She curled up against a bulkhead. She’d be cold tonight. His hull might be sound, but that didn’t keep the damp out of him. He could feel her, still and small against him, unsleeping. Her eyes were probably open, staring into the blackness.

Time passed. A minute or most of the night. Hard to tell. Brashen came down the beach. Paragon knew his stride and the way he muttered to himself when he’d been drinking. Tonight his voice was dark with worry and Paragon judged he was close to the end of his money. Tomorrow he would rebuke himself long for his stupidity, and then go out to spend the last of his coins. Then he’d have to go to sea again.

Paragon would almost miss him. Having company was interesting and exciting. But also annoying and unsettling. They made him think about things better left undisturbed.

‘Paragon,’ Brashen greeted him as he drew near. ‘Permission to come aboard.’

‘Granted. Althea Vestrit’s here.’

A silence. Paragon could almost feel him goggling up at him. ‘She looking for me?’ Brashen asked thickly.

‘No. Me.’ It pleased him inordinately to give the man that answer. ‘Her family has turned her out, and she had nowhere else to go. So she came here.’

‘Oh.’ Another pause. ‘Doesn’t surprise me. Well, the sooner she gives up and goes home, the wiser she’ll be. Though I imagine it will take her a while to come to that.’ Brashen yawned hugely. ‘Does she know I’m living aboard?’ A cautious question, one that begged for a negative answer.

‘Of course,’ Paragon answered smoothly. ‘I told her that you had taken the captain’s cabin and that she’d have to make do elsewhere.’

‘Oh. Well, good for you. Good for you. Good night, then. I’m dead on my feet.’

‘Good night, Brashen. Sleep well.’

A few moments later, Brashen was in the captain’s quarters. A few minutes after that, Paragon felt Althea uncurl. She was trying to move quietly, but she could not conceal herself from him. When she finally reached the door of the aftercastle chamber where Brashen had strung his hammock, she paused. She rapped very lightly on the panelled door. ‘Brash?’ she said cautiously.

‘What?’ he answered readily. He had not been asleep, nor even near sleep. Could he have been waiting? How could he have known she would come to him?

Althea took a deep breath. ‘Can I talk to you?’

‘Can I stop you?’ he asked grumpily. It was evidently a familiar response, for Althea was not put off by it. She set her hand to the door handle, then took it away without opening the door. She leaned on the door and spoke close to it.

‘Do you have a lantern or a candle?’

‘No. Is that what you wanted to talk about?’ His tone seemed to be getting brusquer.

‘No. It’s just that I prefer to see the person I’m talking to.’