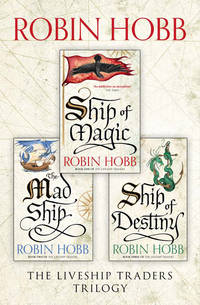

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

‘It was our deal,’ Sorcor pointed out doggedly. ‘For every liveship we chase, we go after one slaver. You agreed.’

‘So I did. I had hoped that after you had dealt with the reality of one “triumph” you would see the futility of it. Look you, Sorcor. Say we strain our crew and resources to take that squalid vessel to Divvytown. Do you think the inhabitants are going to welcome us and rejoice that we put ashore three hundred and fifty half-starved, ragged, sickly wretches to infest their town as beggars, whores and thieves? Do you think these slaves we have “rescued” are going to thank you for abandoning them to their fates as paupers?’

‘They’re thankful now, the whole damn lot of them,’ Sorcor declared stubbornly. ‘And I know in my time, sir, I’d have been damn grateful to be set ashore anywhere, with or without a mouthful of bread or a stitch of clothes, so long as I was a free man and able to breathe clean air.’

‘Very well, very well’ Kennit made a great show of capitulating with a resigned sigh. ‘Let us ride this ass to the end, if we must. Choose a port, Sorcor, and we shall take them there. I shall but ask this. On our way there, those who are able shall begin the task of cleaning out that vessel. And I should like to get underway as soon as we are decently able, while the serpents are still satiated.’ Kennit glanced casually away from Sorcor. It would not do to let him wallow in the gratitude of the freed captives. ‘I shall require you aboard the Marietta, Sorcor. Put Rafo in charge of the other vessel, and assign him some men.’

Sorcor straightened himself. ‘Aye, sir,’ he replied heavily. He trudged from the room, a very different man from the one who had burst in the door exuberant with victory. He shut the door quietly behind himself. For a time, Kennit remained looking at it. He was straining the man’s loyalty; the link that bound them together was forged mostly from Sorcor’s fidelity. He shook his head to himself. It was, perhaps, his own fault. He had taken a simple uneducated sailor with a knack for numbers and navigation and elevated him to the status of mate, taught him what it felt to control men. Thinking, perforce, went with that command. But Sorcor was beginning to think too much. Kennit would soon have to decide which was worth more to him: the mate’s value as second in command, or his own total control of his ship and men. Kennit sighed heavily. Tools blunted so quickly in this trade.

13 TRANSITIONS

BRASHEN AWOKE WITH GRITTY EYES and a crick in his neck. Morning sunlight had penetrated the thick panes of the bay windows that glassed one end of the chamber. It was a thick, murky light, greenish with the dried algae that coated the outside of the windows, but light nonetheless. Enough to alert him that it was daylight and time he was up and about.

He swung out of the hammock to his feet. Guilty. He was guilty of something. Spending all his pay when he had sworn that this time he would be wiser. Yes, but that was a familiar guilt. This was something else, something that bit with sharper teeth. Oh. Althea. The girl had been here last night, begging his advice, or he had dreamed her. And he had given her his bitterest counsels with not a word of hope or an offer of help from him.

He tried to shrug the concern away. After all, what did he owe the girl? Nothing. Not a thing. They hadn’t even really been friends. Too big of a gap in status for that. He had just been the mate on her father’s ship, and she had been the daughter of the captain. No room for a friendship there. And as for the old man, well, yes, Ephron Vestrit had done him a good turn when no one else would, had let him prove himself when no one else would. But the old man was dead now, so that was that.

Besides. Bitter as the advice had been, it was solid. If Brashen could have gone back in time, he would never have quarrelled with his father. He’d have gone to the endless schooling, behaved correctly at the social functions, eschewed drunkenness and cindin, married whoever was chosen for him. And he’d be the heir now to the Trell fortune instead of his little brother.

The thought reminded him that as he was not heir to the Trell fortune and as he had spent the rest of his money last night save for a few odd coins, he had best be worrying more about himself and less about Althea. The girl would have to take care of herself. She’d have to go home. That’s all there was to it. What was the worst that would happen to her, really? They’d marry her off to a suitable man. She’d live in a comfortable home with servants and well prepared food, wear clothing tailored especially for her and go to the endless round of balls and teas and social functions that seemed so essential to Bingtown society and the Traders especially. He snorted softly to himself. He should hope for such a cruel fate to befall him. He scratched at his chest and then his beard. He ran both hands through his hair to smooth it back from his face. Time to find work. He’d best clean himself up and head down to the docks.

‘Good morning,’ he greeted Paragon as he rounded the bow of the ship.

The figurehead looked permanently uncomfortable, fastened to the front of the heavily-leaning ship. Brashen suddenly wondered if it made his back ache, but didn’t have the courage to ask. Paragon had his thickly-muscled arms crossed over his bare chest as he faced out over the glinting water to where other ships came and went from the harbour. He didn’t even turn toward Brashen. ‘Afternoon,’ Paragon corrected him.

‘So it is,’ Brashen agreed. ‘And more than time I got myself down to the docks. Have to look for a new job, you know.’

‘I don’t think she went home,’ Paragon replied. ‘I think that if she went home, she would have gone her old way, up the cliffs and through the woods. Instead, after she said goodbye, I heard her walking away over the beach toward town.’

‘Althea, you mean?’ Brashen asked. He tried to sound unconcerned.

Blind Paragon nodded. ‘She was up at first light.’ The words almost sounded like a reproach. ‘I had just heard the morning birds begin to call when she stirred and came out. Not that she slept much last night.’

‘Well. She had a lot to think about. She may have gone into town this morning, but I’ll wager she goes home before the week is out. After all, where else does she have to go?’

‘Only here, I suppose,’ the ship replied. ‘So. You will seek work today.’

‘If I want to eat, I have to work,’ Brashen agreed. ‘So I’m down to the docks. I think I’ll try the fishing fleet or the slaughter-boats instead of the merchants. I’ve heard a man can rise rapidly aboard one of the whale or dolphin boats. And they hire easy, too. Or so I’ve heard.’

‘Mostly because so many of them die,’ Paragon relentlessly observed. ‘That’s what I heard, back when I was in a position to hear such gossip. That they’re too long at sea and load their ships too heavy, and hire more crew than they need to work the ship because they don’t expect all of them to survive the voyage.’

‘I’ve heard such things, too,’ Brashen reluctantly admitted. He squatted down on his haunches, then sat in the sand beside the beached ship. ‘But what other choice do I have? I should have listened to Captain Vestrit, all those years. I’d have had some money saved up by now if I had.’ He gave a sound that was not a laugh. ‘I wish someone had told me, all those years ago, that I should just swallow my stupid pride and go home.’

Paragon searched deep in his memory. ‘If wishes were horses, beggars would ride,’ he declared, and then smiled, almost pleased with himself. ‘There’s a thought I haven’t recalled for a long time.’

‘And true as ever it was,’ Brashen said disgruntledly. ‘So I’d best take myself down to the harbour and get myself a job on one of these stinking kill-boats. More butchery than sailor’s work is what I’ve heard of them as well.’

‘And dirty work it is, too,’ Paragon agreed. ‘On an honest merchant vessel, a man gets dirty with tar on his hands, or soaked with cold seawater, it’s true. But on a slaughter-ship, it’s blood and offal and oil. Cut your finger and lose a hand to infection. If you don’t die. And on those that take the meat as well, you’ll spend half your sleeping time packing the flesh in tubs of salt. On the greedy ships the sailors end up sleeping right alongside the stinking cargo.’

‘You’re so encouraging,’ Brashen said bleakly. ‘But what choice do I have? None at all.’

Paragon laughed oddly. ‘How can you say that? You have the choice that eludes me, the choice that all men take for granted so that they cannot even see they have it.’

‘What choice is that?’ Brashen asked uneasily. A wild note had come into the ship’s voice, a reckless tone like that of a boy who fantasizes wildly.

‘Stop.’ Paragon spoke the word with breathless desire. ‘Just stop.’

‘Stop what?’

‘Stop being. You are such a fragile thing. Skin thinner than canvas, bones finer than any yard. Inside you are wet as the sea, and as salt, and it all waits to spill from you any time your skin is opened. It is so easy for you to stop being. Open your skin and let your salt blood flow out, let the sea creatures take away your flesh bite by bite, until you are a handful of green slimed bones held together with lines of nibbled sinew. And you won’t know or feel or think anything any more. You will have stopped. Stopped.’

‘I don’t want to stop,’ Brashen said in a low voice. ‘Not like that. No man wants to stop like that.’

‘No man?’ Paragon laughed again, the sound breaking and going high. ‘Oh, I have known a few that did want to stop. I have known a few that did stop. And it ended the same, whether they wanted to or not.’

‘One appears to have a small flaw.’

‘I am sure you are mistaken,’ Althea replied icily. ‘They are well matched and deep hued and of the finest quality. The setting is gold.’ She met the jeweller’s gaze squarely. ‘My father never gave me a gift that was less than the finest quality.’

The jeweller moved his palm and the two small earrings rolled aimlessly in his hand. In her ear lobes, they had looked subtle and sophisticated. In his palm, they merely looked small and simple. ‘Seventeen,’ he offered.

‘I need twenty-three.’ She tried to conceal her relief. She had decided she would not take less than fifteen before she came into the shop. Still, she would wring every coin she could out of the man. Parting with them was not easy, and she had few other resources.

He shook his head. ‘Nineteen. I could go as high as nineteen, but no more than that.’

‘I could take nineteen,’ Althea began, watching his face carefully. When she saw his eyes brighten she added, ‘if you would include two simple gold hoops to replace these.’

A half hour of bargaining later, she left his shop. Two simple silver hoops had replaced the earrings her father had given her on her thirteenth birthday. She tried not to think of them as anything other than a possession she had sold. She still had the memory of her father giving them to her. She did not need the actual jewellery. They would only have been two more things to worry about.

It was odd, the things one took for granted. Easy enough to buy heavy cotton fabric. But then she had to get needle, thread and palm as well. And shears for cutting the fabric. She resolved to make herself a small canvas bag as well to keep these implements in. If she followed her plan to its end, they would be the first possessions she had bought for her new life.

As she walked through the busy market, she saw it with new eyes. It was no longer merely a matter of what she had the coin to pay for and what she would have marked to her family’s account. Suddenly some goods were far beyond her means. Not just lavish fabrics or rich jewellery, but things as simple as a lovely set of combs. She allowed herself to look at them for a few moments longer, holding them against her hair, as she gazed into the cheap street-booth mirror and imagined how they would have looked in her hair at the Summer Ball. The flowing green silk, trimmed with the cream lace — for an instant she could almost see it, could almost step back into the life that had been hers a few scant days ago.

Then the moment passed. Abruptly Althea Vestrit and the Summer Ball seemed like a story she had made up. She wondered how much time would go by before her family opened her sea-chest, and if they would guess which gifts had been intended for whom. She even indulged herself in wondering if her sister and mother would shed a tear or two over the gifts from the daughter and sister they had allowed to be driven away. She smiled a hard smile and set the combs back on the merchant’s tray. No time for such mawkish daydreams. It didn’t matter, she told herself sternly, if they never opened that trunk at all. What did matter was that she needed to find a way to survive. For, contrary to Brashen Trell’s stupid advice, she was not going to go crawling home again like some helpless spoiled girl. No. That would only prove that everything Kyle had said about her was true.

She straightened her spine and moved with renewed purpose through the market. She bought herself a few simple foodstuffs; plums, a wedge of cheese and some rolls, no more than what she would need for the day. Two cheap candles and a tinderbox with flint and steel completed her purchases.

There was little else she could do in town that day, but she was reluctant to leave. Instead she wandered the market for a time, greeting those who recognized her and accepting their condolences on the loss of her father. It no longer stung when they mentioned him; instead it was a part of the conversation to get past, an awkwardness. She did not want to think of him, nor to discuss with relative strangers the grief she felt at her loss. Least of all did she want to be drawn into any conversation that might mention her rift with her family. She wondered how many folk knew of it. Kyle would not want it trumpeted about, but servants would talk, as they always did. Word would get around. She wanted to be gone before the gossip became widespread.

There were not many in Bingtown who recognized her anyway. For that matter, there were few other than the brokers and merchants her father had done ship’s business with that she recognized. She had withdrawn from Bingtown society gradually over the years without ever realizing it. Any other woman her age would have attended at least six gatherings in the last six months, balls and galas and other festivities. She had not been to even one since, oh, the Harvest Ball. Her sailing schedule had not allowed it. And the balls and dinners had seemed unimportant then, something she could return to whenever she wished. Gone now. Over and gone, dresses sewn for her with slippers to match, painting her lips and scenting her throat. Swallowed up in the sea with her father’s body.

The grief she had thought numbed suddenly clutched at her throat. She turned and hurried off, up one street and down another. She blinked her eyes furiously, refusing to let the tears flow. When she had herself under control, she slowed her step and looked around her.

She looked directly into the window of Amber’s shop.

As before, an odd chill of foreboding raced up her back. She could not think why she should feel threatened by a jeweller, but she did. The woman was not even a Trader, not even a proper jeweller. She carved wood, in Sa’s name. Wood, and sold it as jewellery. In that instant, Althea suddenly decided she would see this woman’s goods for herself. With the same resolution as if grasping a nettle, she pushed open the door and swept into the shop.

It was cooler inside, and almost dark after the brightness of the summer street. As her eyes adjusted, Althea saw the place as polished simplicity. The floor was smoothed pine planking. The shelves, too, were simple wood. Amber’s goods were arranged on plain squares of deep-hued fabric on the shelves. Some of the more elaborate necklaces were displayed on the walls behind her counter. There were also pottery bowls full of loose wooden beads in every colour that wood could be.

Her goods were not just jewellery, either. There were simple bowls and platters, carved with rare grace and attention to grain; wooden goblets that could have honoured a king’s table; hair combs carved of scented wood. Nothing had been made of pieces fastened together. In each case, shapes had been discovered in the wood and called forth whole, brought to brilliance by carving and polishing. In one case a chair had been created from a huge wood bole; it was unlike any seat Althea had ever seen before, lacking legs but possessing a smoothed hollow that a slight person could curl into. Ensconced on it, knees folded beside her, sandalled feet peeping from beneath the hem of her robe, was Amber.

It jolted Althea that for an instant she had looked right at Amber and not seen her. It was her skin and hair and eyes, she decided. The woman was all the same colour, even to her clothing and that colour was identical to the honey-toned wood of the chair. She raised one eyebrow quizzically at Althea.

‘You wished to see me?’ she asked quietly.

‘No,’ Althea exclaimed both truthfully and reflexively. Then she made an effort to recover, saying haughtily, ‘I was but curious to see this wooden jewellery that I had heard so much about.’

‘You being such a connoisseur of fine wood,’ Amber nodded.

There was almost no inflection to Amber’s words. A threat. A sarcasm. A simple observation. Althea could not decide. And suddenly it was too much that this woodworker, this artisan, would dare to speak to her so. She was, by Sa, the daughter of a Bingtown Trader, a Bingtown Trader herself by right, and this woman, this upstart, was no more than a newcomer to their settlement who had dared to claim a spot for herself on Rain Wild Street. All Althea’s frustration and anger of the past week suddenly had a target. ‘You refer to my liveship,’ Althea rejoined. It was all in the tone, the challenge as to what right this woman had to speak of her ship at all.

‘Have they legalized slavery here in Bingtown?’ Again there was no real expression to read in that fine featured face. Amber asked the question as if it flowed naturally from Althea’s last words.

‘Of course not! Let the Chalcedeans keep their base customs. Bingtown will never acknowledge them as right.’

‘Ah. But then… ’ the briefest of pauses, ‘you did refer to the liveship as yours? Can you own another living intelligent creature?’

‘Vivacia is mine, as I speak of my sister as mine. Family.’ Althea threw down the words. She could not have said why she suddenly felt so angry.

‘Family. I see.’ Amber flowed upright. She was taller than Althea had expected. Not pretty, much less beautiful, there was still something arresting about her. Her clothing was demure, her carriage graceful. The finely-pleated fabric of her robe echoed the fine plaits of her hair. Her appearance shared her carvings’ simplicity and elegance. Her eyes met Althea’s and held them. ‘You claim sisterhood with wood.’ A smile touched the corners of her lips, making Amber’s mouth suddenly mobile, generous. ‘Perhaps we have more in common than I had dared to hope.’

Even that tiny show of friendliness increased Althea’s wariness. ‘You hoped?’ she said coolly. ‘Why should you hope that we had anything in common at all?’

The smile widened fractionally. ‘Because it would make things easier for both of us.’

Althea refused to be baited into another question.

After a time, Amber sighed a small sigh. ‘Such a stubborn girl. Yet I find myself admiring even that about you.’

‘Did you follow me the other day… the day I saw you down at the docks, near Vivacia?’ Althea’s words came out almost as an accusation, but Amber seemed to take no offence.

‘I could scarcely have followed you,’ she pointed out, ‘since I was there before you. I confess, it crossed my mind when I first saw you that perhaps you were following me…’

‘But the way you were looking at me… ’ Althea objected unwillingly. ‘I do not say that you lie. But you seemed to be looking for me. Watching me.’

Amber nodded slowly, more to herself than to the girl. ‘So it seemed to me, also. And yet it was not you at all that I went seeking.’ She toyed with her earrings, setting first the dragon and then the serpent to swinging. ‘I went to the docks looking for a nine-fingered slave boy, if you can credit that.’ She smiled oddly. ‘You were what found me instead. There is coincidence, and there is fate. I am more than willing to argue with coincidence. But the few times I have argued with fate, I have lost. Badly.’ She shook her head, setting all four of her mismatched earrings to swaying. Her eyes seemed to look inward, recalling other times. Then she looked up and met Althea’s curious gaze, and once more her smile softened her face. ‘But that is not true for all folk. Some folk are meant to argue with fate. And win.’

Althea could think of no reply to that, so held her silence. After a moment, the woman moved to one of her shelves, and took down a basket. At least, at first glance it had appeared to be a basket. As she approached, Althea could see that it had been wrought from a single piece of wood, all excess carved away to leave a lattice of woven strands. Amber shook it as she came nearer, and the contents clicked and rattled pleasantly against one another.

‘Choose one,’ she invited Althea, extending the basket to her. ‘I’d like to make you a gift.’

Within the basket were beads. One glimpse of them, and Althea’s impulse to haughtily refuse the largesse died. Something in the variety of colour and shape caught the eyes and demanded to be touched. Once touched, they pleased the hand. Such a variety of colour and grain and texture. They were all large beads, as big around as Althea’s thumb. Each appeared to be unique. Some were simple abstract designs, others were animals, or flowers. Leaves, birds, a loaf of bread, fish, a tortoise… Althea found she had accepted the basket and was sifting through the contents while Amber watched her with strangely avid eyes. A spider, a twining worm, a ship, a wolf, a berry, an eye, a pudgy baby. Every bead in the basket was desirable, and Althea suddenly understood the charm of the woman’s wares. They were gems of wood and creativity. Another artisan could surely carve as well, wood as fine could be bought, but never before had Althea seen such craft applied to such wood with such precision. The leaping dolphin bead could only have been a dolphin: there was no berry, no cat, no apple hiding in that bit of wood. Only the dolphin had been there, and only Amber could have found it and brought it out of concealment.

Althea could not choose, and yet she kept looking through the beads. Searching for the one that was most perfect. ‘Why do you want to give me a gift?’ she asked suddenly. Her quick glance caught Amber’s pride in her handiwork. She gloried in Althea’s absorption in her beads. The woman’s sallow cheeks were almost warm, her golden eyes glowing like a cat’s before a fire.

When she spoke the warmth rode her words as well. ‘I would like to make you my friend.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I can see that you go through life athwart it. You see the flow of events, you are able to tell how you could most easily fit yourself into it. But you dare to oppose it. And why? Simply because you look at it and say, “this fate does not suit me. I will not allow it to befall me.”’ Amber shook her head, but her small smile made it an affirmation. ‘I have always admired people who can do that. So few do. Many, of course, will rant and rave against the garment fate has woven for them, but they pick it up and don it all the same, and most wear it to the end of their days. You… you would rather go naked into the storm.’ Again the smile, fading as quickly as it blossomed. ‘I cannot abide that you should do that. So I offer you a bead to wear.’

‘You sound like a fortune teller,’ Althea complained, and then her finger touched something in the bottom of the basket. She knew the bead was hers before she gripped it between thumb and forefinger and brought it to the top of the hoard. Yet when she lifted it, she could not say why she had chosen it. An egg. A simple wooden egg, pierced to be worn on a string on her wrist or neck. It was a warm brown, a wood Althea did not know, and the grain of the wood ran around it rather than from end to end. It was plain compared to the other treasures in the basket, and yet it fit perfectly in the hollow of her hand when she closed her fingers about it. It was pleasant to hold, as a kitten is pleasant to stroke. ‘Might I have this one?’ she asked softly and held her breath.