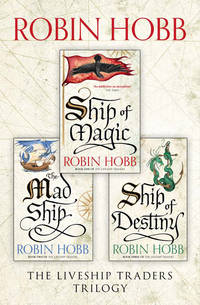

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

She almost laughed at his tone. ‘No. I’m not going to kill your father or anything so rash as that.’ She hesitated, trying to measure what little she knew of the boy. Vivacia had assured her that he was trustworthy. She hoped the young ship was right. ‘I am going to try to out-manoeuvre him, though. But it won’t work if he knows of my plans. So I’m going to ask you to keep my secret.’

‘Why are you telling anyone at all what you plan? A secret is kept best by one,’ he pointed out to her.

That, of course, was the crux of it. She took a breath. ‘Because you are crucial to my plans. Without your promise to aid me, there is no sense in my even acting at all.’

The boy was silent for a time. ‘What you saw, that day, when he hit me. It might make you think I hate him, or wish his downfall. But I don’t.’

‘I’m not going to ask you to do anything wrong, Wintrow,’ Althea replied quickly. ‘Truly. But before I can say any more, I have to ask you to promise to keep my secret.’

It seemed to her that the boy took a very long time considering this. Were all priests so cautious about everything? ‘I will keep your secret,’ he finally said. And she liked that about him. No vows or oaths, just the simple offering of his word. Through the palm of her hand, she felt Vivacia respond with pleasure to her approval of him. Strange, that that should matter to the ship.

‘Thank you,’ she said quietly. She took her courage in both hands, and hoped he would not think she was a fool. ‘Do you remember that day clearly? The day he knocked you down in the dining room?’

‘Most of it,’ the boy said softly. ‘The parts when I was conscious, anyway.’

‘Do you remember what your father said? He swore by Sa, and said that if but one reputable captain would vouch for my seamanship, he’d give my ship back to me. Do you remember that?’ She held her breath.

‘I do,’ Wintrow said quietly.

She put both hands to the ship’s hull. ‘And would you swear by Sa that you heard him say those words?’

‘No.’

Althea’s dreams crashed down through their straw foundations. She should have known it. How could she ever have thought the boy would stand up to his father in as great a matter as this? How could she have been so stupid?

‘I would vouch that I heard him say it,’ Wintrow went on quietly. ‘But I would not swear. A priest of Sa does not swear by Sa.’

Althea’s heart soared. It would be enough, it would have to be enough. ‘You’d give your word, as a man, as to what he said,’ she pressed.

‘Of course. It’s only the truth. But,’ he shook his head down at her, ‘I don’t think it would do you any good. If my father will not keep his word to Sa to give me up to the priesthood, why should he keep his word on an angrily-sworn oath? After all, this ship is worth much more to him than I am. I am sorry to say this to you, Althea, but I think your hopes of regaining your ship that way are groundless.’

‘You let me worry about that,’ she said in a shaky voice. Relief was flowing through her. She had one witness, and she felt she could rely on him. She would say nothing to the boy of the Traders’ Council and the power it held. She had entrusted him with enough of her secret. She would burden him with no more of it. ‘As long as I know you will vouch for the truth, that your father spoke those words, I have hope.’

He received these words in silence. For a time Althea just stood there, her hands on her silent ship. She could almost feel the boy through the ship. His desolation and loneliness.

‘We sail tomorrow,’ he said finally. There was no joy in his voice.

‘I envy you,’ Althea told him.

‘I know you do. I wish we could change places.’

‘I wish it were that simple.’ Althea tried to set aside her jealousy. ‘Wintrow. Trust the ship. She’ll take care of you, and you take good care of her. I’m counting on both of you to watch out for each other.’ She heard in her own voice the ‘doting relative’ tone that she had always hated when she was young. She pushed it away, and spoke as if he were any young boy setting out on his maiden voyage. ‘I believe you’ll grow to love this life and this ship. It’s in your blood, you know. And if you do,’ these words came harder, ‘if you do, and you are true to our ship, when I take her over, I’ll make sure there’s always a place for you aboard her. That is my promise to you.’

‘Somehow I doubt I’ll ever ask you to keep it. It’s not that I don’t like the ship, it’s just that I can’t imagine—’

‘Who are you talking to, boy?’ Torg demanded. His heavy feet thudded across the deck as Althea melted back into the ship’s shadow. She held her breath. Wintrow wouldn’t lie to Torg. She already knew that about him. And she couldn’t stand by and let the boy take a beating for her, but she also couldn’t risk Torg holding her for Kyle.

‘I believe this is my hour with Wintrow,’ Vivacia cut in sharply. ‘Who do you imagine he would be speaking to?’

‘Is there someone on the docks down there?’ Torg demanded. His bushy head was thrust out over the railing, but both the curve of Vivacia’s hull and the deep shadow protected Althea. She held her breath.

‘Why don’t you haul your fat arse down there and see?’ Vivacia asked nastily. Althea clearly heard Wintrow’s gasp of astonishment. It was all she could do to keep from laughing. She sounded just like their cocky ship’s boy, Mild, in one of his bolder moods.

‘Yea? Well, maybe I’ll just do that.’

‘Don’t trip in the dark,’ Vivacia warned him sweetly. ‘It would be a shame if you went overboard and drowned right here by the dock.’ The liveship’s peaceful rocking suddenly increased by the tiniest of increments. And in that moment her adolescent taunting of the man took on a darker edge that stood the hair up on the back of Althea’s neck.

‘You devil ship!’ Torg hissed at her. ‘You don’t scare me. I’m seeing who’s down there.’ Althea heard the thudding of his feet on the deck, but she couldn’t decide if he hurried toward the gangplank or away from the figurehead.

‘Go now!’ Vivacia hissed to her.

‘I’m going. Good luck. My heart sails with you.’ Althea no more than breathed the words, but she knew the ship did not need to hear her speak so long as she touched her. She slipped away from Vivacia, staying to the deepest shadows as she fled. ‘Sa keep them both safe, especially from themselves,’ she said under her breath, and this time she knew that she uttered a true prayer.

Ronica Vestrit waited alone in the kitchen. Outside the night was full, the summer insects chirring, the stars glinting through the trees. Soon the gong at the edge of the field would sound. The thought filled her stomach with butterflies. No. Moths. Moths were more fitting to the night and the rendezvous she awaited.

She had given the servants the night off, and finally told Rache pointedly that she wished to be alone. The slave woman had been so grateful to her lately that it was difficult to be rid of her sad-eyed company. Keffria had her teaching Malta to dance now, and how to hold a fan and even how to discourse with men. Ronica found it appalling that she would entrust her daughter’s instruction in such things to a relative stranger, but understood also that lately Keffria and Malta had not been on the best of terms. She was not informed as to the full extent of their quarrelling, and fervently hoped she would not be. She had problems enough of her own, real and serious problems, without listening to her daughter’s squabbles with her grand-daughter. At least Malta was keeping Rache busy and out from under foot. Most of the time. Twice now Davad had hinted he’d like the slave to be returned to him. Each time Keffria had thanked him so profusely for all Rache’s help, all the while exclaiming that she didn’t know how she’d get along without her, that there had been no gracious way for Davad to simply ask for her back. Ronica wondered how long that tactic would suffice, and what she would do when it did not. Buy the girl? Become a slave-owner herself? The thought made her squeamish. But it was also endlessly aggravating that the poor woman had so attached herself to her. At any time when she was not busy with something else, Rache would be lurking outside whatever chamber Ronica was in, looking for an opportunity to leap forth and be of some service to her. She devoutly wished the woman would find some sort of life for herself. One to replace the one that her slavery had stolen from her? she asked herself wryly.

In the distance, a gong rang, soft as a chime.

She arose nervously and paced around the kitchen, only to come back to the table. She had set it and arranged it herself. There were two tall white candles of finest beeswax to honour her guest. The best china and her finest silver decked the table upon a cloth of heavy cream lacework. Trays of dainty tarts vied with platters of subtly smoked oysters and fresh herbs in bitter sauce. A fine old bottle of wine awaited as well. The grandness of the food was to indicate how she respected her guest, while secrecy and the kitchen setting reminded them both of the old agreements to both protect and defend one another. Nervously Ronica pushed the silver spoons into a minutely improved alignment. Silliness. This was not the first time that she had received a delegate from the Rain Wild Traders. Twice a year since she had been married to Ephron they had come. It was only the first time she had received one since his death. And the first time she had not been able to amass the full payment due.

The small but weighty casket of gold was two measures light. Two measures. Ronica intended to admit it, to bring it up herself before embarrassing questions could be asked. To admit it, and offer an increase in interest on the next payment. What else, after all, could she do? Or the delegate? A partial payment was better than none, and the River Wild folk needed her gold far more than anything else she could offer them. Or so she hoped.

Despite her anticipation, she still startled when the light tap came on the door. ‘Welcome!’ she called without moving to open the door. Quickly she blew out the branch of candles that had illuminated the room. She saved but one, to light the two tall beeswax tapers before she extinguished it. Ornamental hoods of beaten brass with decorative shapes cut out of them were then carefully lowered over the tapers. Now the room was lit only by a scattering of leaf-shaped bits of light. Ronica nodded approval to herself at the effect, and then stepped quickly to open the door herself.

‘I bid you welcome to my home. Enter, and be at home also.’ The words were the old formality, but Ronica’s voice was warm with genuine feeling.

‘Thank you,’ the Rain Wild woman replied. She came in, glanced about to nod her approval at the privacy and the lowered lights. She ungloved her hands, passing the soft leather garments to Ronica and then pushed back the cowl that had sheltered her face and hair. Ronica held herself steady, and met the woman’s eyes with her own. She did not permit her expression to change at all.

‘I have prepared refreshment for you, after your long journey. Will you be seated at my table?’

‘Most gratefully,’ her companion replied.

The two women curtseyed to one another. ‘I, Ronica Vestrit, of the Vestrit family of the Bingtown Traders, make you welcome to my table and my home. I recall all our most ancient pledges to one another, Bingtown to Rain Wilds, and also our private agreement regarding the liveship Vivacia, the product of both our families.’

‘I, Caolwn Festrew, of the Festrew family of the Rain Wild Traders, accept your hospitality of home and table. I recall all our most ancient pledges to one another, Rain Wilds to Bingtown, and also our private agreement regarding the liveship Vivacia, the product of both our families.’

Both women straightened and Caolwn gave a mock sigh of relief that the formalities were over. Ronica was privately relieved that the ceremony was a tradition. Without it, she would never have recognized Caolwn. ‘It’s a lovely table you’ve set, Ronica. But then, in all the years we have met, it has never been anything else.’

‘Thank you, Caolwn.’ Ronica hesitated, but not to have asked would have been the false reticence of pity. ‘I had expected Nelyn this year.’

‘My daughter is no more.’ Caolwn spoke the words quietly.

‘I am sorry to hear that.’ Ronica’s sympathy was genuine.

‘The Rain Wilds are hard on women. Not that they are easy on men.’

‘To outlive your daughter… that must be bitter.’

‘It is. And yet Nelyn gifted us with three children before she went. She will be long remembered for that, and long honoured.’

Ronica nodded slowly. Nelyn had been an only child. Most Rain Wild women considered themselves lucky if they bore one child that lived. For Nelyn to have borne three would indeed make her memory shine. ‘I had taken out the wine for Nelyn,’ Ronica said quietly. ‘You, as I recall, prefer tea. Let me put the kettle on to boil and set aside the wine for you to take back with you.’

‘That is too kind of you.’

‘No. Not at all. When it is drunk, please have all who share it remember Nelyn and how she enjoyed wine.’

Caolwn suddenly lowered her face. The sagging growths on her face bobbed as she did so, but it did not distract Ronica from the tears that shone suddenly in the other woman’s violet eyes. Caolwn shook her head and then heaved a heavy sigh. ‘For so many, Ronica, the formalities are only that. The welcome is forced, the hospitality uncomfortable. But ever since you became a Vestrit and took on the duties of the visit, you have made us feel truly welcome. How can I thank you for that?’

Another woman might have been tempted to tell Caolwn then that the measure of the gold was short. Another woman might not have believed in the sacredness of the old promises and pacts. Ronica did. ‘No thanks are needed. I give you no more than is due you,’ she said, and added, because the words sounded cold, ‘but ceremony or no, pact or no, I believe we would have been friends, we two.’

‘As do I.’

‘So. Let me put on the kettle for tea, then.’ Ronica rose and instantly felt more comfortable in the homely task. As she poured the water into the kettle and blew on the embers in the hearth, she added, ‘Do not wait for me. Tell me, what do you think of the smoked oysters? I got them from Slek, as we always have done, but he has turned the smoking over to his son this year. He was quite critical of the boy, but I believe I like them better.’

Caolwn tasted and agreed with Ronica. Ronica made the tea and brought the kettle to the table and set out two teacups. They sat together and ate and drank and spoke in generalities. Of simple things like their gardens and the weather, of things hard and personal like Ephron’s and Nelyn’s death, and of things that boded ill for them all, such as the current Satrap’s debaucheries and the burgeoning slave-trade that might or might not be related to his head tax on the sale of slaves. There was long and fond reminiscence of their families, and deep discussion of Vivacia and her quickening, as if the ship were a shared grandchild. There was quiet discussion, too, of the influx of new folk to Bingtown, and the lands they were claiming and their efforts to gain seats on the Bingtown Council. This last threatened not only the Bingtown Traders, but the old compact between Bingtown and the Rain Wild Traders that kept them both safe.

The compact was a thing seldom spoken of. It was not discussed, in the same way that neither breathing nor death are topics for conversation. Such things are ever-present and inevitable. In a similar way, Caolwn did not speak to Ronica of the way grief had lined her face and silvered her hair, nor how the years had drawn down the flesh from her high cheekbones and tissued the soft flesh of her throat. Ronica forbore to stare at the scaly growths that threatened Caolwn’s eyesight, nor at the lumpy flesh that was visible even in the parting of her thick bronze hair. The kindness of the dimmed candles could soften but not obscure these scars. Like the pact, these were the visible wounds they bore simply by virtue of who they were.

They shared the steaming cups of tea and the savoury foods. The heavy silver implements ticked against the fine china whilst outside the summer’s night breeze stirred Ronica’s wind chimes to a silvery counterpoint to their conversation. For the space of the meal, they were neighbours sharing a genteel evening of fine food and intelligent conversation. For this, too, was a part of the pact. Despite the miles and differences that separated the two groups of settlers, both Bingtown Traders and Rain Wild Traders would remember that they had come to the Cursed Shore together, partners and friends and kin. And so they would remain.

So it was not until the food was finished and the women were sharing the last cup of cooled tea in the pot, not until the social conversation had died to a natural silence that the time came to discuss the final purpose of Caolwn’s visit. Caolwn took a deep breath and began the formality of the discussion. Long ago the Bingtown Traders had discovered that this was one way to separate business from pleasure. The change in language did not negate the friendship the women shared, but it recognized that in manners of business, different rules applied and must be observed by all. It was a safeguard for a small society in which friends and relatives were also one’s business contacts. ‘The liveship Vivacia has quickened. Is she all that was promised?’

Despite her recent grief, Ronica felt a genuine smile rise onto her face. ‘She is all that was promised, and freely do we acknowledge that.’

‘Then we are pleased to accept that which was promised for her.’

‘As we are pleased to tender it.’ Ronica took a breath and abruptly wished she had brought up the short measure earlier. But it would not have been correct nor fair to make that a part of their friendship. Hard as it was for her to speak it, this was the correct time. She groped for words for this unusual situation. ‘We acknowledge also that we owe you more at this time than we have been able to gather.’ Ronica forced herself to sit straight and meet the surprise in Caolwn’s lavender eyes. ‘We are a full two measures short. We would ask that this additional amount be carried until our next meeting, at which time I assure you we shall pay all that we owe then, and the two additional measures, plus one-quarter measure of additional interest.’

A long silence followed as Caolwn pondered. They both knew the full weight of Bingtown law gave her much leeway in what she could demand as interest for Ronica’s failed payment. Ronica was prepared to hear her demand as much as a full additional two measures. She hoped they would settle between a half and one measure. Even to come up with that much was going to tax her ingenuity to its limits. But when Caolwn did speak, the soft words chilled Ronica’s blood. ‘Blood or gold, the debt is owed,’ Caolwn invoked.

Ronica’s heart skipped in her chest. Who could she mean? None of the answers that came to her pleased her. She tried to keep the quaver out of her voice, she sternly reminded herself that a bargain was a bargain, but one could always try to better the terms. She took the least likely stance. ‘I am but newly widowed,’ she pointed out. ‘And even if I had had the time to complete my mourning, I am scarcely suitable to the pledge. I am too old to bear healthy children to anyone, Caolwn. It has been years since I even hoped I would bear another son to Ephron.’

‘You have daughters,’ Caolwn pointed out carefully.

‘One wed, one missing,’ Ronica quickly agreed. ‘How can I promise you that which I do not have the possession of?’

‘Althea is missing?’

Ronica nodded, feeling again that stab of pain. Not knowing. The greatest dread that any sea-going family had for its members. That some day one would simply disappear, and those at home would never know what became of them…

‘I must ask this,’ Caolwn almost apologized. ‘It is required of me, in duty to my family. Althea would not… hide herself, or flee, to avoid the terms of our bargain?’

‘You have to ask that, and so I take no offence.’ Nonetheless, Ronica was hard put to keep the chill from her voice. ‘Althea is Bingtown to the bone. She would die rather than betray her family’s word on this. Wherever she is, if she still lives, she is bound, and knows she is bound. If you choose to call in our debt, and she knows of it, she will come to answer for it.’

‘I thought as much,’ Caolwn acknowledged warmly. But she still went on implacably, ‘But you have a grand-daughter and grandsons as well, and they are as firmly bound as she. I have two grandsons and a grand-daughter. All approach marriageable age.’

Ronica shook her head, managed a snort of forced laughter. ‘My grandchildren are children still, not ready for marriage for years yet. The only one who is close to that age has sailed off with his father. And he is pledged to Sa’s priesthood,’ she added. ‘It is as I have told you. I cannot pledge you that which I do not possess.’

‘A moment ago, you were willing to pledge gold you did not yet possess,’ Caolwn countered. ‘Gold or blood, it is all a matter of time for the debt to be paid, Ronica. And if we are willing to wait and let you set the time to pay it, perhaps you should be more willing to let us determine the coin of payment.’

Ronica picked up her teacup and found it empty. She stood hastily. ‘Shall I put on the kettle for more tea?’ she inquired politely.

‘Only if it will boil swiftly,’ Caolwn replied. ‘Night will not linger for us to barter, Ronica. The bargain must be set soon. I am reluctant to be found walking about Bingtown by day. There are far too many ignorant folk, unmindful of the ancient bargains that bind us all.’

‘Of course.’ Ronica sat down hastily. She was rattled. She abruptly and vindictively wished that Keffria were here. By all rights, Keffria should be here; the family fortunes were hers to control now, not Ronica’s. Let her face something like this and see how well she would deal with it. A new chill went up Ronica’s spine; she feared she knew how Keffria would deal with it. She’d turn it over to Kyle, who had no inkling of all that was at stake here. He had no concept of what the old covenants were; she doubted that even if he were told, he’d adhere to them. No. He’d see this as a cold business deal. He’d be like those ones who had come to despise the Rain Wild folk, who dealt with them only for the profit involved, with no idea of all Bingtown owed to them. Keffria would surrender the fate of her whole family to Kyle, and he would treat it as if he were buying merchandise.

In the moment of realizing that, Ronica crossed a line. It was not easily done, for it involved sacrificing her honour. But what was honour compared to protecting one’s family and one’s word? If deceptions must be made and lies must be told, then so be it. She could not recall that she had ever in her life decided so coldly to do what she had always perceived as wrong. But then again, she could not recall that she had ever faced so desperate a set of choices before. For one black moment, her soul wailed out to Ephron, to the man who had always stood behind her and supported her in her decisions, and by his trust in her decisions given her faith in herself. She sorely missed that backing just now.

She lifted her eyes and met Caolwn’s hooded gaze. ‘Will you give me some leeway?’ she asked simply. She hesitated a moment, then set the stakes high in order to tempt the other woman. ‘The next payment is due in mid-winter, correct?’

Caolwn nodded.

‘I will owe you twelve measures of gold, for the regular payment.’

Again the woman nodded. This was one of Ephron’s tricks in striking a bargain. Get them agreeing with you, set up a pattern of agreement, and sometimes the competitor could be led into agreeing to a term before he had given it thought.

‘And I will also owe you the two measures of gold I am short this time, plus an additional two measures of gold to make up for the lateness of the payment.’ Ronica tried to keep her voice steady and casual as she named the princely sum. She smiled at Caolwn.