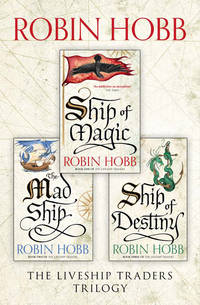

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

She was one of three ‘boys’ aboard the slaughter-ship. The other two, young relatives of the captain, drew the gentler chores. They waited table for both the captain and mate, with a fair chance at getting the leavings from decent meals. They often helped the cook, too, with the lesser chores of preparing food for the main crew. She envied them that the most, she thought to herself, for it often meant they were inside, not only out of the storm’s reach but close to the heat of the cook stove. To Althea, the odd boy, fell the cruder tasks of a ship’s boy. The messy clean-ups, the hauling of buckets of slush and tar, and the make up work of any task that merited an extra man. She had never worked so hard in her life.

She held tight to the mast for a moment longer, just out of reach of yet another wave that swamped the deck. From there to the shelter of the forepeak, she moved in a series of dashes and gasping moments of clinging tight to lines and rails to stay with the vessel as she ploughed through wave after wave. They’d had three solid days of bad weather now. Before the current storm began, Althea had naively believed it would not get much worse. The experienced hands seemed to accept it as part of a normal season on the Outside. They cursed it and demanded of Sa that he end it, but always wound up telling one another tales of worse storms they had endured upon less seaworthy vessels.

‘Ath! Boy! Best get a move on if you want your share of the mess tonight, let alone to eat it while it’s got a breath of warmth in it!’

Reller’s words had more than a bit of threat to them, but despite that tone the old hand stayed on deck, watching her until she gained his side. Together they went below, sliding the hatch tight shut behind them. Althea paused on the step behind Reller to dash the water from her face and arms and then wring out the thick queue of her hair. Then she followed him down into the belly of the ship.

A few months ago, she would have said it was a cold, wet, smelly place. Now it was haven if not home, a place where the wind could not drive the rain into you so fiercely. The yellow light of a lantern was almost welcoming. She could hear food being served out, a wooden ladle clacking against the inside of a kettle, and hastened to be sure of getting her rightful share.

On board the Reaper, there were no crew quarters. Each man found himself a sleeping spot and claimed it. The more desirable ones had to be periodically defended with fists and oaths. There was a small area in the midst of the cargo hold that the men had claimed as a sort of den. Here the kettle of food was brought by one of the ship’s boys and rationed out in dollops as soon as they came off watch. There was no table, no benches to sit on, save your sea-chest if you had one. For the rest, there was only the deck and the odd keg of oil to lean against. The plates were wooden trenchers, cleaned only with a wiping of fingers or bread, when they had bread. Ship’s biscuit was the rule, and in a storm like this, there was small chance that Cook had tried to bake anything. Althea made her way through a jungle of dangling garments. Wet clothing hung everywhere from pegs and hooks in a pretence of drying. Althea shrugged out of her oilskin, won last week gambling with Oyo, and hung it on the peg she had claimed as her own.

Reller’s threat had not been idle. He was serving himself as Althea approached, and like every man on the ship, he took what he wanted with no regard for who came after. Althea snatched up an empty trencher and waited eagerly for him to be out of the way. She sensed he was taking his time about it, trying to bait her into complaint, but she had learned the hard way to be wiser than that. Anyone could cuff a ship’s boy, and they did not need the excuse of his whining to do it. Better to keep silent and get half a ladle of soup than to complain and get only a cuff for her supper. Reller crouched over the kettle and ladled up scoop after scoop from the shallow puddle of what was left. Althea swallowed and waited her turn.

When Reller saw she would not be baited, he almost smiled. Instead he told her, ‘There, lad. I’ve left you a few lumps in the bottom. Clean up the kettle, and then run it back to Cook.’

Althea knew this was a kindness, in a way. He could have taken all and left her naught but scrapings and no one would have even considered speaking against him. She was happy to take the kettle and all and retire to her claimed spot to devour it.

She had a good place, all things considered. She had wedged her meagre belongings up in a place where the curve of the hull met the deck above. It made it near impossible to stand upright. Here she had slung her hammock. No one else could have curled himself small enough to sleep comfortably there. She had found she could retreat there and be relatively undisturbed while she slept; no one was brushing past her in wet rain gear. So she took the kettle to her corner and settled down with it.

She scooped up what broth was left with her mug and drank it down. It was not hot — in fact the grease had congealed in small floating blobs — but it was warmer than the rain outside and the fat tasted good to her. True to his word, Reller had left some lumps. Potato, or turnip or perhaps just a doughy blob of something meant to be a dumpling but not cooked enough. Althea didn’t care. Her fingers scooped it up and she ate it. With a hard round of ship’s biscuit she scraped the kettle clean of every last remnant of food.

She had no sooner swallowed the last bite than a great weariness rose up in her. She was cold and wet and ached in every bone. More than anything, she longed simply to drag down her blanket, roll up in it and close her eyes. But Reller had told her she had to take the kettle back to the cook. She knew better than to wait until after she had slept. That would be seen as shirking. She thought Reller himself might turn a blind eye to it, but if he did not, or if the cook complained, she could catch the end of a rope for it. She couldn’t afford that. With a sound that could have been a whimper, she crept from her sleeping space with the kettle cradled in her arms.

She had to brave the storm-washed deck again to reach the galley. She made it in two dashes, holding onto the kettle as tightly as she held onto the ship. If she let something like that wash overboard, she knew they’d make her wish she’d gone with it. When she got to the galley, she had to kick and beat upon the door; the cook had secured it from inside. When he did let her in, it was with a scowl. Wordlessly, she offered him the kettle, and tried not to look longingly at the fire in its box behind him. If you were favoured by the cook, you could stay long enough to warm yourself. The truly privileged could hang a shirt or a pair of trousers in the galley, where they actually dried completely. Althea was not even marginally favoured. The cook gestured her out the door as soon as she set the kettle down.

On the trip back, she misjudged her timing. Later, she would blame it on the cook for turning her so swiftly out of the galley. She thought she could make it in one dash. Instead the ship seemed to dive straight into a mountain of water. She felt her desperate fingers brush the line she lunged for, but she did not make good her hold. The water simply swept her feet out from under her and rushed her on her belly across the deck. She kicked and struggled wildly, trying to claw some kind of a hold on the deck with fingers and toes. The water was in her eyes and up her nose; she could not see nor find breath to shout for help. An eternal instant later, she was slammed into the ship’s railing. She took a glancing blow to the side of her head that rang darkness before her eyes and near tore her ear off. For a brief moment, she knew nothing but to hold tight to the railing with both hands as she lay belly down on the swamped deck. Water rushed past her in its hurry to be overboard. She clung to the ship, feeling the seawater cascade past her, but unable to lift her head high enough to get a clear breath. She knew, too, that if she waited until the water was completely gone before she got to her feet, the next wave would catch her as well. If she didn’t manage to get up now, she wasn’t ever going to get up. She tried to move but her legs were jelly.

A hand grabbed the back of her shirt, hauled her choking to her knees. ‘You’re plugging the scuppers!’ someone exclaimed in disgust. She hung from his grip like a drowned kitten. There was air against her face, mixed with driving rain, but before she could take it in, she had to gag out the water in her mouth and nose. ‘Hang on!’ she heard him shout and she wrapped her legs and arms about his legs. She managed one gargly breath of air before the water hit them both.

She felt his body swing with the impact of the water and thought surely they would both be torn loose from the ship. But an instant later, as the water retreated, he struck her a cuff to the side of the head that loosened her grip on him. Suddenly he was moving across the deck, dragging her behind him, her pigtail and shirt caught together in his grip. He hauled her up a mast; as soon as her feet and hands felt the familiar rope, they clung to them and propelled her up of their own accord. The next wave that rushed over the deck went by beneath her. She gagged and then spat a quantity of seawater into it. She blew her nose into her hand and shook it clean. With her first lungful of air, she said, ‘Thank you.’

‘You stupid little deck rat! You damn near got us both killed.’ Anger and fear vied in the man’s voice.

‘I know. I’m sorry.’ She spoke no louder than she had to in order to be heard through the storm.

‘Sorry? I’ll make you a sight more than just sorry. I’ll kick your arse till your nose bleeds.’

He lifted his fist and Althea braced herself to take the blow. She knew that by ship’s custom she had it coming. When after a moment it did not land, she opened her eyes.

Brashen peered at her through the darkness. He looked more shaken than he had when he’d first dragged her up from the water. ‘Damn you. I didn’t even recognize you.’

She made a small gesture that could have been a shrug. Her eyes did not meet his.

Another wave made its passage across the ship. Again the ship began its wallowing climb.

‘So. How have you been doing?’ Brashen’s voice was pitched low, as if he feared to be overheard talking to her. A mate was not expected to have chummy little chats with the ship’s boy. Since discovering her, he had avoided all contact with her.

‘As you see,’ Althea said quietly. She hated this. She abruptly hated Brashen, not for anything he had done, but because he was seeing her this way. Ground down to someone less than dirt under his feet. ‘I get by. I’m surviving.’

‘I’d help you if I could.’ He sounded angry with her. ‘But you know I can’t. If I take any interest in you at all, someone will suspect. I’ve already made it plain to several of the crew that I’ve no interest in… other men.’ He suddenly sounded awkward. A part of Althea found the irony in this. Clinging to rigging on this scummy ship in the middle of a storm after he’d just offered to kick her arse, and he could not bring himself to speak of sex with her. For fear of offending her dignity. ‘On a ship like this, any kindness I showed you would be construed only one way. Then someone else would decide he fancied you, too. Once they found out you were a woman…’

‘You needn’t explain. I’m not stupid,’ Althea interrupted to stop his litany. Didn’t he know she lived aboard the scum-infested tub?

‘You’re not? Then what are you doing aboard?’ He threw the last bitter words over his shoulder before he dropped from the rigging to the deck. Agile as a cat, quick as a monkey, he made his way swiftly to the bow of the ship, leaving her clinging in the rigging and staring after him.

‘The same thing you are,’ she replied snidely to his last words. It didn’t matter that he could not hear them. The next time the water cleared the deck, she followed Brashen’s example, but with considerably less grace and skill. Moments later, she was below decks, listening to the rush of water all around her. The Reaper moved through the water like a barrel. She sighed heavily, and once more dashed the water from her face and bare arms. She wrung out her queue and shook her wet feet like a cat before padding back to her corner. Her clothing was sodden against her skin, chilling her. She changed hastily into clothing that was merely damp, then wrung out what she had had on. She shook it out, hung her shirt and trousers on a peg to drip and tugged her blanket out from its hiding-place. It was damp and smelled musty, but it was wool. Damp or not, it would hold the heat of her body. And that was the only warmth she had. She rolled herself into it and then curled up small in the darkness. So much for Reller’s kindness. It had got her half-drowned and cost her half an hour of her sleep. She closed her eyes and let go of consciousness.

But sleep betrayed her. As weary as she was, oblivion would not come to her. She tried to relax, but could not remember how to loosen the muscles in her lined brow. It was the words with Brashen, she decided. Somehow they brought the situation back to her as a whole. Often she went for days without catching so much as a glimpse of him. She wasn’t on his watch; their lives and duties seldom intersected. And when she had no reminders of what her life once had been, she could simply go from hour to hour, doing what she had to do to survive. She could give all her attention to being the ship’s boy and think no further than the next watch.

Brashen’s face, Brashen’s eyes, were crueller than any mirror. He pitied her. He could not look at her without betraying to her all that she had become, and worse, all that she had never been. Bitterest of all, perhaps, was seeing him recognize as surely as Althea herself had, that Kyle had been right. She had been her Papa’s spoiled little darling, doing no more than playing at being a sailor. She recalled with shame the pride she had taken in how swiftly she could run the rigging of the Vivacia. But her time aloft had mostly been during warm summer days, and whenever she was wearied or bored with the tasks of it, she could simply come down and find something else to amuse herself. Spending an hour or two splicing and sewing was not the same as six hours of frantically hasty sailwork after a piece of canvas had split and needed to be immediately replaced. Her mother had fretted over her callouses and rough hands; now her palms were as hardened and thick-skinned as the soles of her feet had been; and the soles of her feet were cracked and black.

That, she decided, was the worst aspect of her life. Finding out that she was no more than adequate as a sailor. No matter how tough she got, she was simply not as strong as the larger men on the ship. She had passed herself off as a fourteen-year-old boy to get this position aboard the Reaper. Even if she had wished to stay with this slaughter-tub, in a year or so they were bound to notice she wasn’t growing any larger or stronger. They wouldn’t keep her on. She’d wind up in some foreign port with no prospects at all.

She stared up into the darkness. At the end of this voyage, she had planned to ask for a ship’s ticket. She still would, and she’d probably get it. But she wondered now if it would be enough. Oh, it would be the endorsement of a captain, and perhaps she could use it to make Kyle live up to his thoughtless oath. But she feared it would be a hollow triumph. Having a stamped bit of leather to show she had survived this voyage was not what she had wanted. She had wanted to vindicate herself, to prove to all, not just Kyle, that she was good at her chosen life, a worthy captain to say nothing of being a competent sailor. Now, in the brief times when she did think about it, it seemed to her that she had only proved the opposite to herself. What had seemed daring and bold when she’d begun it back in Bingtown now seemed merely childish and stupid. She’d run away to sea, dressed as a boy, taking the first position that was offered to her.

Why, she asked herself now. Why? Why hadn’t she gone to one of the other liveships and asked to be taken on as a hand? Would they have refused as Brashen had said they would? Or could she, even now, be sleeping aboard a merchant vessel cruising down the Inside Passage, sure of both wages and recommendation at the end of the voyage? Why had it seemed so important to her that she be hired anonymously, that she prove herself worthy without either her name or her father’s reputation to fall back on? It had seemed such a spirited thing to do, on those summer evenings in Bingtown when she had sat cross-legged in the back room of Amber’s store and sewed her ship’s trousers. Now it merely seemed childish.

Amber had helped her. But for her help, with both needlework and readily shared meals, Althea would never have been able to do it. Amber’s sudden befriending of her had always puzzled Althea. Now it seemed to her that perhaps Amber had actually been intent on propelling her into danger. Her fingers crept up to touch the serpent’s egg bead that she wore on a single strand of leather about her neck. The touch of it almost warmed her fingers and she shook her head at the darkness. No. Amber had been her friend, one of the few rare women-friends she’d ever had. She’d taken her in for the days of high summer, helped her cut and sew her boy’s clothing. More, Amber had donned man’s clothing herself, and schooled Althea in how to move and walk and sit as if she were male. She had, she told Althea, once been an actress in a small company. Hence she’d played many roles, as both sexes.

‘Bring your voice from here,’ she’d instructed her, prodding Althea below her ribs. ‘If you have to talk. But speak as little as you can. You’ll be less likely to betray yourself, and you’ll be better accepted. A good listener of any sex is rare. Be one, and it will make up for anything else perceived as a fault.’ Amber had also shown her how to wrap her breasts flat to her chest in such a way that the binding cloth appeared to be no more than another shirt worn under her outer shirt. Amber had shown her how to fold dark-coloured stockings to use as blood rags. ‘Dirty socks you can always explain,’ Amber had told her. ‘Cultivate a fastidious personality. Wash your clothing twice as much as anyone else does, and no one will question it after a time. And learn to need less sleep. For you will either have to rise before any others or stay up later in order to keep the privacy of your body. And this I caution you most of all. Trust no one with your secret. It is not a secret a man can keep. If one man aboard the ship knows you are a woman, then they all will.’

This was the only area in which Amber had, perhaps, been mistaken. For Brashen knew she was a woman, and he had not betrayed her. At least, he hadn’t so far. A sudden irony came to Althea. She grinned bitterly to herself. In my own way I took your advice, Brashen. I arranged to be reborn as a boy, and not one called Vestrit.

Brashen lay on his bunk and studied the wall opposite him. It was not far from his face. Was a time, he thought ruefully, when I would have scorned this cabin as a clothes-closet. Now he knew what a luxury even a tiny space to himself could be. True, there was scarce room to turn around once a man was inside, but he did have his own berth, and no one slept in it but him. There were pegs for his clothing, and a corner just large enough to hold his sea-chest. In the bunk, he could brace himself against the ledge that confined his body and almost sleep secure when he was off watch. The captain’s and the mate’s cabins were substantially larger and better appointed, even on a tub like this. But then on many ships the second mate had no better quarters than the crew. He was grateful for this tiny corner of quiet, even if it had come to him by the deaths of three men.

He had shipped as an ordinary seaman, and spent the first part of his trip growling and elbowing in the forecastle with the rest of his watch. Early on, he had realized he had not only more experience but a stronger drive to do his job well than the rest of his fellows. The Reaper was a slaughter-ship out of Candletown far to the south, on the northern border of Jamaillia. When the ship had left the town many months ago in spring, it had left with a mostly conscripted crew. A handful of professional sailors were the backbone of the crew, charged with battering the newcomers into shape as sailors. Some were debtors, their work sold by their creditors as a means of forcing them to pay back what they owed. Others were simple criminals purchased from the Satrap’s jails. Those who had been pickpockets and thieves had soon learned better or perished; the close quarters aboard a slaughter-ship did not encourage a man to be tolerant of such vice in his fellows. It was not a crew that worked with a will, nor one whose members were likely to survive the rigours of the trip. By the time the Reaper reached Bingtown, she’d lost a third of her crew to sickness, accidents and violence aboard. The two thirds that remained were survivors; they’d learned to sail, they’d learned to pursue the slow-moving turtles and the so-called brack-whales of the southern coast inlets and lagoons. Their services were not, of course, to be confused with the skills of the professional hunters and skinners who rode the ship in the comparative comfort of a dry chamber and idleness. The dozen or so men of that ilk never set a hand to a line or stood a watch; they idled until their time of slaughter and blood. Then they worked with a fury, sometimes going without sleep for days at a time while the reaping was good. But they were not sailors and they were not crew. They would not lose their lives save that the whole ship went down or one of their prey turned on them successfully.

The ship had beat her way north on the outside of the pirate islands, hunting, slaughtering and rendering all the way. At Bingtown, the Reaper had put in to take on clean water and supplies and to make such repairs as they had the coin to pay for. The mate had also actively recruited more crew, for the journey out to the Barren Islands. It had been nearly the only ship in the harbour that was hiring.

The storms between Bingtown and the Barrens were as notorious as the multitude of sea mammals that swarmed there just prior to the winter migration. They’d be fat with the summer feedings, the sleek coats of the young ones large enough to be worth the skinning and unscarred from battles for mates or food. It was worth braving the storms of autumn to take such prizes — soft furs, the thick layer of fat, and beneath it all the lean, dark-red flesh that tasted both of sea and land. The casks of salt that had filled the hold when they left Candletown would soon be packed instead with salted slabs of the prized meat, with hogsheads of the fine rendered oil, while the scraped hides would be packed with salt and rolled thick to await tanning. It would be a cargo rich enough to make the Reaper’s owners dance with glee, while those debtors who survived to reach Candletown again would emerge from their ordeal as free men. The hunters and skinners would claim a percentage of the total take and begin to take bids on their services for the next season based on how well they had done this time. As for the true sailors who had taken the ship all that way and brought her back safely, they would have a pocketful of coins to jingle, enough to keep them in drink and women until it was time to sail again for the Barrens.

A good life, Brashen thought wryly. Such a fine berth as he had won for himself. It had not taken much. All he had had to do was scramble swiftly enough to catch the mate’s eye and then the captain’s. That, and the vicious storm that had carried off two men and crippled the third who was a likely candidate for this berth.

Yet it was not any peculiar guilt at having stepped over dead men to claim this place and the responsibilities that went with it that bothered him tonight. No. It was the thought of Althea Vestrit, his benefactor’s daughter, curled in wet misery in the hold in the close company of such men as festered there. ‘There’s nothing I can do about it.’ He spoke the words aloud, as if by giving them to air he could make them ease his conscience. He hadn’t seen her come aboard in Bingtown; even if he had, he wouldn’t have recognized her easily. She was a convincing mimic as a sailor lad; he had to give her that.