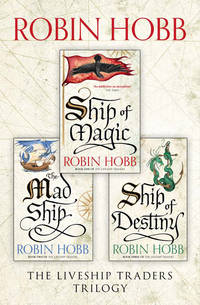

The Complete Liveship Traders Trilogy: Ship of Magic, The Mad Ship, Ship of Destiny

And Ronica, because he was so ill, had swallowed her ire that he could so disparage the life that she led, and thrust down the jealousy she felt for her own daughter’s freedom and careless ways. Nor had she mentioned that the way the family fortunes were going, there might be a need for Althea to marry well. Sourly Ronica now mused that if they tamed the girl down, perhaps they could wed her off to one of their creditors, preferably a generous one who would forgive the family’s debt as a wedding gift. Ronica shook her head slowly. No. In his own subtle way, Ephron had taken the argument right to her weakest position. She had married Ephron because she’d fallen in love with him. Just as Keffria had succumbed to Kyle’s blond charms. And despite all the family faced, she hoped that when Althea married, she would love the man. She looked with heartsick fondness on the man she still loved.

Afternoon sunlight pouring in the window was making Ephron frown in his sleep. Ronica got up quietly to draw a curtain across the window. She no longer enjoyed that view. Once it had been a great pleasure to look out that window and see the sturdy trunk and branches of their marriage tree. Now it stood stark and leafless in the midst of the summer garden, bare as any skeleton. She felt a shiver up her back as she drew the curtain across the sight.

He had so looked forward to seeing their tree in bloom. But that spring the bud blight that had always spared the tree struck it full force. The flowers browned and fell suddenly to the earth. Not a one opened for them, and the scent of the rotting petals was like funeral herbs. Neither of them spoke of it as an omen. Neither of them had ever been religious people. But shortly after that, Ephron had begun to cough again. Weak little bird coughs that brought up nothing, until the day that he had wiped his mouth and nose, and then frowned at the scarlet tracings of blood on the napkin.

It had been the longest summer of her life. The hot days were a torment to him. He’d declared that breathing the heavy humid air was no better than breathing his own blood, and then coughed up stringy clots as if to prove his point. The flesh had fallen from his body, and he’d had neither the appetite nor the will to take in sustenance. Still, they did not speak of his death. It hovered over the whole house, more oppressive than the humid summer air; Ronica would not give it any more substance by speaking of it.

She moved silently, carefully picking up a small table and setting it close to her bedside chair. She brought back to it her accounting ledgers, her ink and pen, and a handful of receipts to be entered. She bent to her work, frowning as she did so. The entries she made in her small, precise hand did nothing to cheer her. Somehow it was more depressing now that she knew Ephron would insist on looking over the book the next time he awoke. For years he had taken almost no interest in the running of the farms and orchards and other holdings. ‘I leave them in your competent hands, my dear,’ he would tell her whenever she tried to present her worries to him. ‘I’ll take care of the ship and see she pays herself off in my lifetime. To you I entrust the rest.’

It had been both heady and frightening to have her husband trust her so. It was not that unusual for wives to manage the wealth they brought with them as dowries, and many of the women in time quietly handled substantially more than that, but when Ephron Vestrit openly turned over the directing of almost all his holdings to his young wife, it near scandalized Bingtown. It was no longer the fashion for women to take a hand in the financial end of things; it smacked of their old pioneer life to revert to such a thing. The old Bingtown Traders had always been known for their innovative ways, but as they prospered, it had become a symbol of wealth to keep one’s womenfolk free of such tasks. Now it was seen as both plebeian and foolish to so entrust a Trader’s fortune to a woman.

Ronica had known that it was not just his fortune Ephron had put in her hands, but his reputation as well. She had vowed to be worthy of that trust. For more than thirty years their holdings had prospered. There had been bad harvests, grain blights, frosts both early and late to contend with, but always a good fruit crop had balanced out the grain not doing well, or the sheep had prospered when the orchards suffered. Had they not had the heavy debt from constructing the Vivacia to pay off, they would have been wealthy folk. Even as it had been, they’d been comfortable, and in some years a bit more than that.

Not so the last five years. In that time they had slipped from comfortable to well-off, and then to what Ronica had come to think of as anxious. The money went out almost as swiftly as it came in, and always it seemed she was asking a creditor to wait a day or a week until she could pay him. Over and over she had gone to Ephron to beg his advice. He had demurred to her, telling her to sell off what was not profitable to shore up what was. But that was the problem. Most of the farms and orchards were doing as well as they ever had in producing. But there were cheap slave-grown grain and fruit from Chalced to compete with, and the damned Red Ship Wars to the north destroying trade there, and the thrice-damned pirates to the south. Shipments sent forth never arrived at their destinations, and expected profits did not return. She feared constantly for the safety of her husband and daughter always out at sea, but Ephron seemed to class pirates with stormy weather; they were simply among the hazards a good sea-captain had to face. He might come home from his own voyages and tell her unnerving tales of running from sinister ships, but all his stories had happy endings. No pirate vessel could hope to run down a liveship. When she had tried to tell him of how severely the war and the pirates were affecting the rest of the family fortunes, he would laugh good-naturedly and tell her that he and the Vivacia would but work all the harder until things came right. Back then he had not been interested in seeing her account books nor in hearing the grim tidings of the other merchants and traders. Ronica recalled with frustration that he had seemed able to see only that his own voyages were successful, and that the trees bore fruit and the grain ripened in their fields as it always had. He’d take a brisk trip out to one of the holdings, give a cursory glance to their accounts, and take himself and Althea back to sea, leaving Ronica to cope.

Only once had she ever been bold enough to suggest to him that perhaps they might have to return to trading up the Rain Wild River. They had the rights, and the contacts, and the liveship. In the days of his grandmother and father, that had been the principal source of their trade goods. But ever since the Blood Plague days, he had refused to go up the Rain Wild River. There was no concrete evidence that the sickness had come from the Rain Wilds. Besides, who could say where a sickness came from? There was no sense in blaming themselves, and in cutting themselves off from the most profitable part of their trade. But Ephron had only shaken his head, and made her promise never to suggest it again. He had nothing against the Rain Wild Traders, and he did not deny their trade goods were exotic and beautiful. But he had taken it into his head that one could not traffic in magic, even peripherally, without paying a price. He would, he’d told her, rather that they be poor than risk it.

First she’d had to let the apple orchards go, and with them the tiny winery that had been her pride. The grape arbours had been sold off as well, and that had been hard for her. She had acquired them when she and Ephron were but newly weds, her first new venture, and it had been her joy to see them prosper. Still, she would have been a fool to keep them at the price that had been offered. It had been enough to keep their other holdings afloat for a year. And so it continued. As war and the pirates tightened the financial noose on Bingtown, she’d had to surrender one venture after another to keep the others afloat. It shamed her. She had been a Carrock and like the Vestrits, the Carrocks were one of the original Bingtown Trader families. It did nothing for her fears to see the other old families foundering as hungry young merchants moved into Bingtown, buying up old holdings and changing the way things had always been done. They’d brought the slave-trade to Bingtown, at first as merchandise on their way to the Chalced States, but lately it seemed that the flow of slaves that passed through Bingtown surpassed every other trade. But the slaves didn’t flow through any more. More and more of the fields and orchards were being worked with slaves now. Oh, the landowners claimed they were indentured servants, but all knew that such ‘servants’ were routinely sent on to Chalced and sold as slaves if they proved unwilling workers. More than a few of them wore slave tattoos on their faces. It was yet another Chalcedean custom that seemed to have gained popularity in Jamaillia and was now beginning to be accepted in Bingtown as well. It was these ‘New Traders’, Ronica thought bitterly. They might have come to Bingtown from Jamaillia City, but the baggage they brought with them seemed directly imported from Chalced.

Ostensibly, it was still against the law in Bingtown to keep slaves except as transient trade goods, but that did not seem to bother the New Traders. A few bribes at the Tax Docks, and the Satrap’s treasury agents became very gullible, more than willing to believe that folk with tattooed faces and chained in coffles were indentured servants, not slaves at all. The slaves would have gained nothing by speaking the truth of their situation. The Old Traders’ Council had complained in vain. Now even a few of the old families had begun to flout the slavery law. Traders like Davad Restart, she thought bitterly. She supposed Davad had to do as he did, to stay afloat in these hard times. Had not he as much as said so to her last month, when she had been worrying aloud about her wheat fields? He’d all but suggested she cut her costs by working the fields with slaves. He’d even implied he could arrange it all for her, for a small slice of the profits. Ronica did not like to think of how sorely she’d been tempted to take that advice.

She was writing the last dreary entry into her account books when the rustle of Rache’s skirts broke her attention. She lifted her eyes to the servant girl. Ronica was so weary of the mixture of anger and sorrow she always saw in Rache’s face. It was as if the woman expected her to do something to mend her life for her. Couldn’t she see that Ronica had all she could cope with between her dying husband and tottering finances? Ronica knew that Davad had meant well when he’d insisted on sending Rache over to help her, but sometimes she just wished the woman would disappear. There was no gracious way to be rid of her, however, and no matter how irritated Ronica became with her, she could never quite bring herself to send her back to Davad. Ephron had always disapproved of slavery. Ronica thought it was something that most slaves had brought on themselves, but somehow it seemed disrespectful to Ephron to condemn this woman to slavery when she had helped care for him as he was dying. No matter how poorly she had helped.

‘Well?’ she asked tartly of Rache when she just stood there.

‘Davad is here to see you, lady,’ Rache mumbled.

‘Trader Restart, you mean?’ Ronica corrected her.

Rache bobbed her head in silent acknowledgement. Ronica set her teeth, then gave it up. ‘I’ll see him in the sitting room,’ she instructed Rache, and then followed the girl’s sullen eyes to where Davad already stood in the door.

As always he was immaculately groomed, and as always everything about his clothes was subtly wrong. His leggings bagged slightly at the knees, and the embroidered doublet he wore was laced just tightly enough that he had spoiled the lines of it: it made his modest belly seem a bulging pot. He had oiled his dark hair into ringlets, but most of the curl had fallen from them so it hung in greasy locks. Even if the curl had stayed, it was a style more suited to a much younger man.

Somewhere Ronica found the aplomb to smile back at him as she set down her pen and shut her account book. She hoped the ink was dry. She started to rise, but Davad motioned her to stay as she was. Another small gesture from him sent Rache scurrying from the room as Davad advanced to Ephron’s bedside.

‘How is he?’ Davad asked, softening his deep voice.

‘As you see,’ Ronica replied quietly. She set aside her irritation at his calm assumption of welcome in her husband’s sickroom. She also put aside her embarrassment that he had caught her at her totting up, with ink on the side of her hand and her brow wrinkled from staring at her own finely penned numbers. Davad meant well, she was sure. How he had managed to grow up in one of Bingtown’s old Trader families and still have such a hazy idea of good manners, she would never know. Without invitation, he drew up a chair to sit on the other side of Ephron’s bed. Ronica winced as he dragged it across the floor, but Ephron did not stir. When the portly Trader was settled, he gestured at her accounting books.

‘And how do they go?’ he asked familiarly.

‘No better nor worse than any other Trader’s these days, I am sure.’ She evaded his prying. ‘War, blight and pirates trouble all of us. All we can do is to persevere and wait for better days. And how are you today, Davad?’ She tried to recall him to his manners. He put a splay-fingered hand on his belly meaningfully. ‘I have been better. I have just come from Fullerjon’s table; his cook has an abominable hand with the spices, and Fullerjon has not the tongue to tell it.’ He leaned back in his chair and heaved a martyred sigh. ‘But one must be polite, and eat what is offered, I suppose.’

Ronica stifled her irritation. She gestured toward the door. ‘We could take our conversation to the terrace. A glass of buttermilk might help to settle your indigestion as well.’ She made as if to rise, but Davad did not budge.

‘No, no, thank you all the same. I’ve but come on a brief errand. A glass of wine would be welcome, however. You and Ephron always did keep the best cellars in town.’

‘I do not wish Ephron disturbed,’ she said bluntly.

‘Oh, I’ll take care to speak softly. Though, to be frank, I would rather bring this offer to him than to his wife. Do you expect him to wake soon?’

‘No.’ Ronica heard the edge in her voice, and coughed slightly, as if it had been the result of a dry throat. ‘But if you wish to tell me the terms of whatever offer you bring, I shall present it to Ephron as soon as he awakens.’ She pretended to have forgotten his request for wine. It was petty, but she had learned to take her small satisfactions where she could.

‘Certainly, certainly. All Bingtown knows you hold his purse-strings. And his trust, I might add, of course.’ He nodded jovially at her as if this were a high compliment.

‘The offer?’ Ronica pushed.

‘From Fullerjon, of course. I believe it was his sole purpose in inviting me to share his table this noon, if you can credit that. The little upstart seems to think I have nothing better to do than act as his go-between with the better families in town. Did I not think that you and Ephron could benefit from his offer just now, I’d have told him as much. As things stand, I did not want to alienate him, you understand. He’s no more than a greedy little merchant, but…’ He shrugged his shoulders eloquently. ‘One can scarce do business in Bingtown these days without them.’

‘And his offer was?’ Ronica prompted.

‘Ah yes. Your bottom lands. He wishes to buy them.’ He espied the platter of small biscuits and fruits that she kept at Ephron’s bedside and helped himself to a biscuit.

Ronica was shocked. ‘Those are part of the original grant lands of the Vestrit family. Satrap Esclepius himself granted those lands.’

‘Ah, well, you and I know the significance of such things, but newcomers such as Fullerjon…’ Davad began placatingly.

‘The granting of those lands was what made the Vestrit family a Trader family. They were part of the Satrap’s agreement with the Traders. Two hundred leffers of good land, to any family willing to go north and settle on the Cursed Shores, to brave the dangers of life near Rain River. There were few enough willing to in those days. All know that strangeness flows down the Rain River as swiftly as the waters. Those bottom lands, and a share in the monopoly on the trade goods of the Rain River are what make the Vestrits a Trader family. Can you seriously think any Trader family would sell off their grant lands?’ She was angry now.

‘You needn’t give me a history lesson, Ronica Vestrit.’ Davad rebuked her mildly. He helped himself to another biscuit. ‘Need I remind you that my family came here in the same expedition? The Restarts are as much Traders as the Vestrits. I know what those lands mean.’

‘Then how can you even bring such an offer here?’ she demanded hotly.

‘Because half of Bingtown knows how desperate things have become for you. Look here, woman. You haven’t the capital to hire the workers to farm those lands properly. Fullerjon does. And buying them would increase his land ownership to the point where he’d be qualified to petition for a seat on the Bingtown Council. Between the two of us, I think that’s all he’s really after anyway. It needn’t be your bottom lands, though that is what he’d like. Offer him something else; he’ll probably buy it from you.’ Davad leaned back with a dissatisfied look on his face. ‘Sell him the wheat fields. You can’t work them properly anyway.’

‘And he can gain a seat on the Bingtown Council. So he can vote to bring slaves to Bingtown. And work the lands I’ve sold him with slaves and sell the grain he grows cheaper than I can compete with. Or you, for that matter, or any other honest Trader. Davad Restart, use your mind. This offer not only asks me to betray the Vestrit family, but all of us. We’ve enough greedy little merchants on the Bingtown Council already. The Old Traders’ Council is barely able to keep them in check. I shan’t be the one to sell land and a council seat to another latecomer upstart.’

Davad started to speak, then visibly controlled himself. He folded his small hands on his lap. ‘It’s going to happen, Ronica.’ She heard true regret in his voice. ‘The day of the Old Traders is fading. The wars and the pirates bit into us too deeply. And now that the wars are mostly over, these merchants have come, swarming over us like fleas on a dying rabbit. They’ll suck us dry. We need their money in order to recover, so they force us to sell cheap what cost us so dear in blood and children.’ For a moment his voice faltered. Ronica suddenly recalled that the year of the Blood Plague had carried off all his children as well as left him a widower. He had never remarried.

‘It’s going to happen, Ronica,’ he repeated. ‘And those of us who survive will be the ones who have learned to adapt. When our families first settled Bingtown, they were poor and hungry and oh so adaptable. We’ve lost that. We’ve become what we fled. Fat and traditionalist and desperate to hang on to our monopolies. The only reason we despise the new merchants who have started moving in is that they remind us so much of ourselves. Or rather of our great-great-grandparents, and the tales we’ve heard of them.’

For a moment, Ronica almost felt inclined to agree with him. Then she felt a rush of anger. ‘They are nothing like the original Traders! They were wolves, these are eye-picking carrion birds! When the first Carrock set foot on this shore, he risked everything. He sold all he had for his ship-share, and mortgaged half of whatever he might gain for the next twenty years to the Satrap. And for what? For a grant of land and a guarantee of a share in the monopoly. What land? Why, whatever acreage he could claim. What monopoly? Why, on whatever goods he might discover that would be worth trading in. And where was this wonderful bargain granted to him? On a stretch of coast that for hundreds of years had been known as the Cursed Shores, a place where even the gods themselves did not claim dominion. And what did they find here? Diseases unknown before, strangeness that drove men mad overnight, and the doom that half our children are born not quite human.’

Davad suddenly went pale and made shushing motions with his hands. But Ronica was relentless.

‘Do you know what it does to a woman, Davad, to carry something inside her for nine months, not knowing if it’s the child and heir they’ve been praying for, or if it’s a malformed monster that her husband must strangle with his own hands? Or something in between? You must know what it does to a man. As I recall, your Dorill was pregnant three times yet you only had two children.’

‘And the Blood Plague carried them all off,’ Davad admitted brokenly. He suddenly lowered his face into his hands and Ronica was sorry, sorry for all she had said, and sorry for this pathetic shell of a man who had no wife to tell him to relace his tunic and scold the tailor for badly-fitting trousers. She was sorry for all of them, born in Bingtown to die in Bingtown, and in between to carry on the curse-plagued bargain their forebears had struck. Perhaps the worst part of that bargain was that one and all, they had come to love Bingtown and the surrounding green hills and valleys. Verdant as a jungle, soil black and rich in the hand, crystal water in the streams, and abundant game in the forests, it offered them wealth beyond the dreams of the sea-weary and draggled immigrants who had first been brave enough to anchor in the Bingtown harbour. In the end, the real contract had been made, not with the Satrap who nominally claimed these shores, but with the land itself. Beauty and fertility balanced with disease and death.

And something more, she admitted to herself. There was something in calling oneself a Bingtown Trader, in not only braving all the strangeness that came down the Rain River, but claiming it for one’s own. The first Traders had tried to establish their settlement at the mouth of the Rain River itself. They had built their homes on the river’s edge, using the roots of the stilt-trees as foundations for their cottages, and stringing bridges from home to home. The rising and falling river had rushed by beneath their floors and the wild storm winds had rocked their tree-houses at night. Sometimes the very earth itself would heave and tremble, and then the river might suddenly run milky white and deadly, for a day or a month. For two years the settlers had abided there, despite insects and fevers and the swift river that devoured anything that fell into it. Yet it had not been those hardships, but the strangeness that had finally driven them away. The little company of Traders had been pushed south by death and disease and the odd panics that might strike a woman as she kneaded the bread, the furies of self-destruction that could come on a man gathering wood and send him leaping into the river. Of three hundred and seven households that had been the original Traders, sixty-two families had survived that first three years. Even now, from Bingtown to the mouth of the Rain River there stretched a trail of abandoned townsites that marked the path of their attempts at settlement. Finally, here in Bingtown, on the shores of Trader Bay, they had found a tolerable distance from the Rain River and all that flowed down it. Of those families that had chosen to remain as settlers on the Rain River, the less said the better. The Rain Wild Traders were kin and a necessary part of all Bingtown was. She acknowledged that. Still.

‘Davad?’ She reached across Ephron to touch their old friend’s arm gently. ‘I’m sorry. I spoke too roughly, of things better left unmentioned.’

‘It’s all right,’ he lied into his hands. He lifted a pale face to meet her eyes. ‘What we Traders do not speak of amongst ourselves is common talk among these newcomers. Have not you noticed how few bring their wives and daughters with them? They do not come here to settle. They will buy land, yes, and sit on the Council and wring wealth out of Bingtown, but in between they will sail back to Jamaillia. That is where they will wed and keep their wives, where their children will be born, that is where they will go to spend their ageing years and send but a son or two here to manage things.’ He snorted disdainfully. ‘The Three-Ships Immigrants I could respect. They came here, and when we honestly told them what price this sanctuary would cost them, they still stayed. But this wave of newcomers arrive hoping only to reap the harvest we have watered with our blood.’