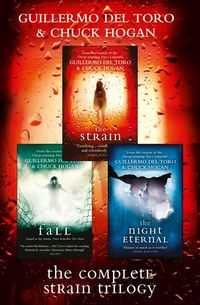

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

“Captain Redfern?” said Jim, his voice echoing in the stairwell. He fumbled out his phone as he descended, wanting to call Eph. The display said NO SERVICE because he was underground now. He pushed through the door into the basement hallway and, distracted by his phone, never saw Redfern running at him from the side.

When Nora, searching the hospital, went through the door from the stairwell into the basement hallway, she found Jim sitting against the wall with his legs splayed. He had a sleepy expression on his face.

Captain Redfern was standing barefoot over him, his johnny-bare back to her. Something hanging from his mouth spilled driblets of blood to the floor.

“Jim!” she yelled, though Jim did not react in any way to her voice. Captain Redfern stiffened, however. When he turned to her, Nora saw nothing in his mouth. She was shocked by his color, formerly quite pale, now florid and flushed. The front of his johnny was indeed bloodstained, and blood also rimmed his lips. Her first thought was that he was in the grip of some sort of seizure. She feared he had bitten off a chunk of his tongue and was swallowing blood.

Closer, her diagnosis became less certain. Redfern’s pupils were dead black, the sclera red where it should have been white. His mouth hung open strangely, disjointedly, as though his jaw had been reset on a lower hinge. And there was a heat coming off him that was extreme, beyond the warmth of any normal, natural fever.

“Captain Redfern,” she said, calling him over and over, trying to snap him out of it. He advanced on her with a look of vulturelike hunger in his filmy eyes. Jim remained slumped on the floor, not moving. Redfern was obviously violent, and Nora wished she had a weapon. She looked around, seeing only a hospital phone, 555 the alert code.

She grabbed the receiver off the wall, barely getting it into her hand before Redfern attacked, throwing her to the floor. Nora kept hold of the receiver, its cord pulling right out of the wall. Redfern had maniacal strength, descending on her and pinning her arms hard to the polished floor. His face strained and his throat bucked. She thought he was about to vomit on her.

Nora was screaming when Eph came flying from the stairwell door, throwing his weight into Redfern’s torso, sending him sprawling, off her. Eph righted himself and held out a cautionary hand toward his patient, dragging himself up from the floor now. “Hold on—”

Redfern emitted a hissing sound. Not snakelike, but throaty. His black eyes were flat and vacant as he started to smile. Or seemed to smile, using those same facial muscles—only, when his mouth opened, it kept on opening.

His lower jaw descended and out wriggled something pink and fleshy that was not his tongue. It was longer, more muscular and complex … and squirming. As though he had swallowed a live squid, and one of its tentacles was still thrashing about desperately inside his mouth.

Eph jumped back. He grabbed the IV tree to keep from falling, and then upended it, using it like a prod to keep Redfern and that thing in his mouth at bay. Redfern grabbed the steel stand and then the thing in his mouth lashed out. It extended the six-foot distance of the IV tree, Eph spinning out of the way just in time. He heard the flap of the end of the appendage—narrowed, like a fleshy stinger—strike the wall. Redfern flung the stand to the side, cracking it in half, Eph tumbling with it backward into a room.

Redfern entered after him, still with that hungry look in his black-and-red eyes. Eph searched around wildly for anything that would help him keep this guy away from him, finding only a trephine in a charger on a shelf. A trephine is a surgical instrument with a spinning cylindrical blade generally used for cutting open the human skull during autopsy. The helicopter-type blade whirred to life, and Redfern advanced, his stinger mostly retracted yet still lolling, with flanking sacs of flesh pulsing at its sides. Before Redfern could attack again, Eph tried to cut it.

He missed, slicing a chunk out of the pilot’s neck. White blood kicked out, just as he had seen in the morgue, not spraying out arterially but spilling down his front. Eph dropped the trephine before its whirring blades could spit the substance at him. Redfern grabbed at his neck, and Eph picked up the nearest heavy object he could find, a fire extinguisher. He used the butt end of it to batter Redfern in the face—his hideous stinger Eph’s prime target. Eph smashed him twice more, Redfern’s head snapping back with the last blow, his spine emitting an audible crack.

Redfern collapsed, his body giving out. Eph dropped the tank and stumbled back, looking in horror at what he had done.

Nora came rushing in wielding a broken piece of the IV tree, then saw Redfern lying in a heap. She dropped the shaft and rushed to Eph, who caught her in his arms.

“Are you okay?” he said.

She nodded, her hand over her mouth. She pointed at Redfern and Eph looked down and saw the worms wriggling out of his neck. Reddish worms, as though blood filled, spilling out of Redfern’s neck like cockroaches fleeing a room when a light is turned on. Eph and Nora backed up to the open doorway.

“What the hell just happened?” said Eph.

Nora’s hand came away from her mouth. “Mr. Leech,” she said.

They heard a groan from the hallway—Jim—and rushed out to tend to him.

INTERLUDE III Revolt, 1943

AUGUST WAS SEARING THROUGH THE CALENDAR AND Abraham Setrakian, laying out beams for a suspended roof, felt its burden more than most. The sun was baking him, every day it was like this. But even more than that, he had come to loathe the night—his bunk and his dreams of home, which had formerly been his only respite from the horror of the death camp—and was now a hostage to two equally merciless masters.

The Dark Thing, Sardu, now spaced his visits to a regular pattern of twice-a-week feedings in Setrakian’s barracks, and probably the same in the other barracks as well. The deaths went completely unnoticed by guards and prisoners alike. The Ukrainian guards wrote the corpses off as suicides, and to the SS it meant only a change in a ledger entry.

In the months since the Sardu-Thing’s first visit, Setrakian—obsessed with the notion of defeating such evil—learned as much as he could from other local prisoners about an ancient Roman crypt located somewhere in the outlying forest. There, he was now certain, the Thing had made its lair, from whence it emerged each night to slake its ungodly thirst.

If Setrakian ever understood true thirst, it was that day. Water carriers circulated among the prisoners constantly, though many of them themselves fell prey to heat seizures. The burning hole was well fed that day. Setrakian had managed to collect what he needed: a length of raw white oak, and a bit of silver for the tip. That was the old way to dispose of the strigoi, the vampire. He had sharpened the tip for days before treating it with the silver. Smuggling it into his barracks alone took the better part of two weeks of planning. He had lodged it in an empty space directly behind his bed. If the guards ever found it, they would execute him on the spot, for there was no mistaking the shape of the hardwood as a weapon.

The night before, Sardu had entered the camp late, later than usual. Setrakian had lain very still, waiting patiently for it to begin feeding on an infirm Romani. He felt revulsion and remorse, and prayed for forgiveness—but it was a necessary part of his plan, for the half-gorged creature would be less alert.

The blue light of impending dawn filtered through the small grated windows at the east end of the barracks. Just what Setrakian had been waiting for. He pricked his index finger, drawing a perfect crimson pearl out of his dry flesh. Yet he was completely unprepared for what happened next.

He had never heard the Thing utter a sound. It conducted its unholy repast in utter silence. But now, at the smell of young Setrakian’s blood, the Thing groaned. The sound reminded Setrakian of the creaking sound of dry wood when twisted, or the sputter of water down a clogged drain.

In a matter of seconds, the Thing was at Setrakian’s side.

As the young man cautiously slid his hand back, reaching for the stake, the two locked eyes. Setrakian couldn’t help but turn toward it when it moved near his bed.

The Thing smiled at him.

“Ages since we fed looking into living eyes,” the Thing said. “Ages …”

Its breath smelled of earth and of copper, and its tongue clicked in its mouth. Its deep voice sounded like an amalgam of many voices, poured forth as though lubricated by human blood.

“Sardu …” whispered Setrakian, unable to keep the name to himself.

The beady, burnished eyes of the Thing opened wider, and for a fleeting moment they looked almost human.

“He is not alone in this body,” it hissed. “How dare you call to him?”

Setrakian gripped the stake behind his bed, slowly sliding it out …

“A man has the right to be called by his own name before meeting God,” said Setrakian, with the righteousness of youth.

The Thing gurgled with joy. “Then, young thing, you may tell me yours …”

Setrakian made his move then, but the silver tip of the stake made a tiny scraping noise, revealing its presence a mere instant before it flew toward the Thing’s heart.

But that instant was enough. The Thing uncoiled its claw and stopped the weapon an inch from its own chest.

Setrakian tried to free himself, striking out with his other hand, but the Thing stopped that too. It lacerated the side of Setrakian’s neck with the tip of its stinger—just a gash, coming as fast as the blink of an eye, enough to inject him with the paralyzing agent.

Now it held the young man firmly by both hands. It raised him up from the bed.

“But you will not meet God,” the Thing said. “For I am personally acquainted with him, and I know him to be gone …”

Setrakian was on the verge of fainting from the vicelike pressure the claws exerted upon his hands. The hands that had kept him alive for so long in that camp. His brain was bursting with pain, mouth gaping, lungs gasping for breath, but no scream would surge from within.

The Thing looked deep into Setrakian’s eyes then, and saw his soul.

“Abraham Setrakian,” it purred. “A name so soft, so sweet, for a boy so full of spirit …” It moved close to his face. “But why destroy me, boy? Why am I so deserving of your wrath, when around you you find even more death in my absence. I am not the monster here. It is God. Your God and mine, the absent Father who left us all so long ago … In your eyes I see what you fear most, young Abraham, and it is not me … It is the pit. So now you shall see what happens when I feed you to it and God does nothing to stop it.”

And then, with a brutal cracking noise, the Thing shattered the bones in the hands of young Abraham.

The boy fell to the floor, curled in a ball of pain, his crushed fingers near his chest. He had landed in a faint pool of sunlight.

Dawn.

The Thing hissed, attempting to move close to him one more time.

But the prisoners in the barracks began to stir, and as young Abraham lost consciousness, the Thing vanished.

Abraham was discovered bleeding and injured before roll call. He was dispatched to the infirmary from which wounded prisoners never returned. A carpenter with broken hands served no purpose in the camp, and the head overseer immediately approved his disposal. He was dragged out to the burning hole with the rest of the roll-call failures, made to kneel in a line. Thick, greasy, black smoke occluded the sun above, searing hot and merciless. Setrakian was stripped and dragged to the very edge, cradling his destroyed hands, shivering in fear as he gazed into the pit.

The searing pit. The hungry flames twisting, the greasy smoke lifting away in a kind of hypnotic ballet. And the rhythm of the execution line—gunshot, gun carriage clicking, the soft bouncing tinkle of the bullet casing against the dirt ground—lulled him into a death trance. Staring down into the flames stripping away flesh and bone, unveiling man for what he is: mere matter. Disposable, crushable, flammable sacks of meat—easily revertible to carbon.

The Thing was an expert in horror, but this human horror indeed exceeded any other possible fate. Not only because it was without mercy, but because it was acted upon rationally and without compulsion. It was a choice. The killing was unrelated to the larger war, and served no purpose other than evil. Men chose to do this to other men and invented reasons and places and myths in order to satisfy their desire in a logical and methodical way.

As the Nazi officer mechanically shot each man in the back of the head and kicked them forward into the consuming pit, Abraham’s will eroded. He felt nausea, not at the smells or the sights but at the knowledge—the certainty—that God was no longer in his heart. Only this pit.

The young man wept at his failure and the failure of his faith as he felt the muzzle of the Luger press against the bare skin—

Another mouth at his neck—

And then he heard the shots. From across the yard, a work crew of prisoners had taken the observation towers and were now overriding the camp, shooting every uniformed officer in sight.

The man at his back went away. Leaving Setrakian poised at the edge of that pit.

A Pole next to him in line stood and started to run—and the will seeped back into young Setrakian’s body. Hands clutched to his chest, he found himself up and running, naked, toward the camouflaged barbed-wire fence.

Gunfire all around him. Guards and prisoners bursting with blood and falling. Smoke now, and not just from the pit: fires starting all across the camp. He made it to the fence, near some others and somehow, with anonymous hands lifting him to the top, doing what his broken hands could not, he fell to the other side.

He lay on the ground, rifle rounds and machine-gun fire ripping into the dirt around him—and again, helping hands and arms raised him up, lifting him to his feet. And as his unseen helpers were torn apart by bullets, Setrakian ran and ran and found himself crying … for in the absence of God he had found Man. Man killing man, man helping man, both of them anonymous: the scourge and the blessing.

A matter of choice.

For miles he ran, even as Austrian reinforcements closed in. His feet were sliced open, his toes shattered by rocks, but nothing could stop him now that he was beyond the fence. His mind was of a single purpose as he finally reached the woods and collapsed in the darkness, hiding in the night.

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan

Setrakian shifted his weight, trying to get comfortable on the bench against the wall inside the precinct house holding tank. He had waited in a glass-walled prebooking area all night, stuck with many of the same thieves, drunks, and perverts he was caged in with now. During the long wait, he had had sufficient time to consider the scene he had made outside the coroner’s office, and realized he had spoiled his best chance at reaching the federal disease control agency in the person of Dr. Goodweather.

Of course he had come off like a crazy old man. Maybe he was slipping. Going wobbly like a gyroscope at the end of its revolutions. Maybe the years of waiting for this moment, lived on that line between dread and hope, had taken their toll.

Part of getting old is checking oneself constantly. Keeping a good firm grip on the handrail. Making sure you’re still you.

No. He knew what he knew. The only thing wrong with him now was that he was being driven mad by desperation. Here he was, being held captive in a police station in Midtown Manhattan, while all around him …

Be smart, you old fool. Find a way out of here. You’ve worked your way out of far worse places than this.

He replayed the scene from the booking area in his mind. In the middle of his giving his name and address and having the charges of disturbing the peace and criminal trespass explained to him, and signing a property form for his walking stick (“It is of immense personal significance,” he had told the sergeant) and his heart pills, a Mexican youth of eighteen or nineteen was brought in, wrists handcuffed behind him. The youth had been roughed up, his face scratched, his shirt torn.

What caught Setrakian’s eye were the burn holes in his black pants and across his shirt.

“This is bullshit, man!” said the youth, arms pulled tight behind him, leaning back as he was pushed ahead by detectives. “That puto was crazy. Dude was loco, he was naked, running in the streets. Attacking people. He came at us!” The detectives dropped him, hard, into a chair. “You didn’t see him, man. That fucker bled white. He had this fucking … this thing in his mouth! It wasn’t fucking human!”

One of the detectives came over to Setrakian’s booking sergeant’s cubicle, wiping sweat off his face with a paper towel. “Crazy-ass Mex. Two-time juvie loser, just turned eighteen. Killed a man this time, in a fight. Him and a buddy, must have jumped the guy, stripped off his clothes. Tried to roll him right in the middle of Times Square.”

The booking sergeant rolled his eyes and continued pecking at his keyboard. He asked Setrakian another question, but Setrakian didn’t hear him. He barely felt the seat beneath him, or the warped fists his old, broken hands made. Panic nearly overtook him at the thought of facing the unfaceable again. He saw the future. He saw families torn apart, annihilation, an apocalypse of agonies. Darkness reigning over light. Hell on earth.

At that moment Setrakian felt like the oldest man on the planet.

Suddenly, his dark panic was supplanted by an equally dark impulse: revenge. A second chance. The resistance, the fight—the coming war—it had to begin with him.

Strigoi.

The plague had started.

Isolation Ward,

Jamaica Hospital Medical Center

JIM KENT, still in his street clothes, lying in the hospital bed, sputtered, “This is ridiculous. I feel fine.”

Eph and Nora stood on either side of the bed. “Let’s just call it a precaution, then,” said Eph.

“Nothing happened. He must have knocked me down as I went through the door. I think I blacked out for a minute. Maybe a low-grade concussion.”

Nora nodded. “It’s just that … you’re one of us, Jim. We want to make sure everything checks out.”

“But—why in isolation?”

“Why not?” Eph forced a smile. “We’re here already. And look—you’ve got an entire wing of the hospital to yourself. Best bargain in New York City.”

Jim’s smile showed that he wasn’t convinced. “All right,” he said finally. “But can I at least have my phone so I can feel like I’m contributing?”

Eph said, “I think we can arrange that. After a few tests.”

“And—please tell Sylvia I’m all right. She’s going to be panicked.”

“Right,” said Eph. “We’ll call her as soon as we get out of here.”

They left shaken, pausing before exiting the isolation unit. Nora said, “We have to tell him.”

“Tell him what?” said Eph, a little too sharply. “We have to find out what we’re dealing with first.”

Outside the unit, a woman with wiry hair pulled back under a wide headband stood up from the plastic chair she had pulled in from the lobby. Jim shared an apartment in the East Eighties with his girlfriend, Sylvia, a horoscope writer for the New York Post. She brought five cats to the relationship, and he brought one finch, making for a very tense household. “Can I go in?” said Sylvia.

“Sorry, Sylvia. Rules of the isolation wing—only medical personnel. But Jim said to tell you that he’s feeling fine.”

Sylvia gripped Eph’s arm. “What do you say?”

Eph said, tactfully, “He looks very healthy. We want to run some tests, just in case.”

“They said he passed out, he was a bit woozy. Why the isolation ward?”

“You know how we work, Sylvia. Rule out all the bad stuff. Go step by step.”

Sylvia looked to Nora for female reassurance.

Nora nodded and said, “We’ll get him back to you as soon as we can.”

Downstairs, in the hospital basement, Eph and Nora found an administrator waiting for them at the door to the morgue. “Dr. Goodweather, this is completely irregular. This door is never to be locked, and the hospital insists on being informed of what is going on—”

“I’m sorry, Ms. Graham,” said Eph, reading her name off her hospital ID, “but this is official CDC business.” He hated pulling rank like a bureaucrat, but occasionally being a government employee had its advantages. He took out the key he had appropriated and unlocked the door, entering with Nora. “Thank you for your cooperation,” he said, locking it again behind him.

The lights came on automatically. Redfern’s body lay underneath a sheet on a steel table. Eph selected a pair of gloves from the box near the light switch and opened up a cart of autopsy instruments.

“Eph,” said Nora, pulling on gloves herself. “We don’t even have a death certificate yet. You can’t just cut him open.”

“We don’t have time for formalities. Not with Jim up there. And besides—I don’t even know how we’re going to explain his death in the first place. Any way you look at it, I murdered this man. My own patient.”

“In self-defense.”

“I know that. You know that. But I certainly don’t have the time to waste explaining that to the police.”

He took the large scalpel and drew it down Redfern’s chest, making the Y incision from the left and right collarbones down on two diagonals to the top of the sternum, then straight down the center line of the trunk, over the abdomen to the pubis bone. He then peeled back the skin and underlying muscles, exposing the rib cage and the abdominal apron. He didn’t have time to perform a full medical autopsy. But he did need to confirm some things that had shown up on Redfern’s incomplete MRI.

He used a soft rubber hose to wash away the white, blood-like leakage and viewed the major organs beneath the rib cage. The chest cavity was a mess, cluttered with gross black masses fed by spindly feeders, veinlike offshoots attached to the pilot’s shriveled organs.

“Good God,” said Nora.

Eph studied the growths through the ribs. “It’s taken him over. Look at the heart.”

It was misshapen, shrunken. The arterial structure had been altered also, the circulatory system grown more simplified, the arteries themselves covered over with a dark, cancerous blight.

Nora said, “Impossible. We’re only thirty-six hours out from the plane landing.”

Eph flayed Redfern’s neck then, exposing his throat. The new construct was rooted in the midneck, grown out of the vestibular folds. The protuberance that apparently acted as a stinger lay in its retracted state. It connected straight into the trachea, in fact fusing with it, much like a cancerous growth. Eph elected not to anatomize further just yet, hoping instead to remove the muscle or organ or whatever it was in its entirety at a later time, to study it whole and determine its function.

Eph’s phone rang then. He turned so that Nora could pull it from his pocket with her clean gloves. “It’s the chief medical examiner’s office,” she said, reading the display. She answered it for him, and after listening for a few moments, told the caller, “We’ll be right there.”

Office of the Chief Medical Examiner, Manhattan

DIRECTOR BARNES ARRIVED at the OCME at Thirtieth and First at the same time as Eph and Nora. He stepped from his car, unmistakable in his goatee and navy-style uniform. The intersection was jammed with police cars and TV news crews set up outside the turquoise front of the morgue building.