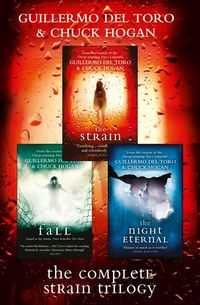

The Complete Strain Trilogy: The Strain, The Fall, The Night Eternal

The doors parted, swinging out a few inches on their own. The sun was straight overhead now, the shed dark inside but for residual light from the small window. She stood before the opening, trying to see inside.

“Ansel?”

She saw a shadow stirring.

“Ansel … you have to keep quieter, at night … Mr. Otish from across the street called the police, thinking it was the dogs … the dogs …”

She grew teary, everything threatening to spill out of her.

“I … I almost told him about you. I don’t know what to do, Ansel. What is the right thing? I am so lost here. Please … I need you …”

She was reaching for the doors when a moanlike cry shocked her. He drove at the shed doors—at her—attacking from within. Only the staked chain jerked him back, strangling an animal roar in his throat. But as the doors burst open, she saw—before her own scream, before she slammed the doors on him like shutters on a ferocious hurricane—her husband crouched in the dirt, naked but for the dog collar tight around his straining neck, his mouth black and open. He had torn away most of his hair just as he had torn off his clothes, his pale, blue-veined body filthy from sleeping—hiding—beneath the dirt like a dead thing that had burrowed into its own grave. He bared his bloodstained teeth, eyes rolling back inside his head, recoiling from the sun. A demon. She wound the chain back through the handles with wildly fluttering hands and fastened the lock, then turned and fled back into her house.

Vestry Street, Tribeca

THE LIMOUSINE took Gabriel Bolivar straight to his personal physician’s office in a building with an underground garage. Dr. Ronald Box was the primary physician for many New York-based celebrities of film, television, and music. He was not a Rock Doc, or a Dr. Feelgood, a pure prescription-writing machine—although he was liberal with his electronic pen. He was a trained internist, and well versed in drug-rehabilitation centers, the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis C, and other fame-related maladies.

Bolivar went up the elevator in a wheelchair, clad only in a black robe, sunk into himself like an old man. His long, silken black hair had gone dry and was falling out in patches. He covered his face with thin, arthritic-like hands so that none would recognize him. His throat was so swollen and raw that he could barely speak.

Dr. Box saw him right away. He was looking through images transferred electronically from the clinic. The images came with a note of apology from the head clinician, who saw only the results and not the patient, promising to repair their machines and suggesting another round of tests in a day or two. But, looking at Bolivar, Dr. Box didn’t think it was their equipment that was corrupt. He went over Bolivar with his stethoscope, listening to his heart, asking him to breathe. He tried to look into Bolivar’s throat, but the patient declined, wordlessly, his black-red eyes glaring in pain.

“How long have you had those contact lenses in?” asked Dr. Box.

Bolivar’s mouth curled into a jagged snarl and he shook his head.

Dr. Box looked at the linebacker standing by the door, wearing a driver’s uniform. Bolivar’s bodyguard, Elijah—six foot six, two hundred and sixty pounds—looked very nervous, and Dr. Box was becoming frightened. He examined the rock star’s hands, which appeared aged and sore yet not at all fragile. He tried to check the lymph nodes under his jaw, but the pain was too great. The temperature reading from the clinic had read 123° F, a human impossibility, and yet, standing near enough to feel the heat coming off Bolivar, Dr. Box believed it.

Dr. Box stood back.

“I don’t really know how to tell you this, Gabriel. Your body, it seems, is riddled with malignant neoplasms. That’s cancer. I’m seeing carcinoma, sarcoma, and lymphoma, and all of it is wildly metastasized. There is no medical precedent for this that I am aware of, although I will insist on involving some experts in the field.”

Bolivar just sat there, listening, a baleful look in his discolored eyes.

“I don’t know what it is, but something has you in its grip. I do mean that literally. As far as I can tell, your heart has ceased beating on its own. It appears that the cancer is … manipulating the organ now. Beating it for you. Your lungs, the same. They are being invaded and … almost absorbed, transformed. As though …” Dr. Box was just realizing this now. “As though you are in the midst of a metamorphosis. Clinically, you could be considered deceased. It appears that the cancer is keeping you alive. I don’t know what else to say to you. Your organs are all failing, but your cancer … well, your cancer is doing great.”

Bolivar sat staring into the middle distance with those frightful eyes. His neck bucked slightly, as though he were trying to formulate speech but could not get his voice past an obstruction.

Dr. Box said, “I want to check you in to Sloan-Kettering right away. We can do so under an assumed name with a dummy social security number. It’s the top cancer hospital in the country. I want Mr. Elijah to drive you there now—”

Bolivar emitted a rumbling chest groan that was an unmistakable no. He placed his hands on the armrests of the wheelchair and Elijah came forward to brace the rear handles as Bolivar rose to his feet. He took a moment regaining his balance, then picked at the belt of his robe with his sore hands, the knot falling open.

Revealed beneath his robe was his limp penis, blackened and shriveled, ready to drop from his groin like a diseased fig from a dying tree.

Bronxville

NEEVA, THE LUSSES’ NANNY, still very much rattled by the events of the past twenty-four hours, left the children in the care of her nephew, Emile, while her daughter, Sebastiane, drove her back to Bronxville. She had kept the Luss children, Keene and his eight-year-old sister, Audrey, eating Frosted Flakes for lunch, and cubed fruit, things Neeva had taken with her from the Luss house when she’d fled.

Now she was returning for more. The Luss children wouldn’t eat her Haitian cooking, and—more pressingly—Neeva had forgotten Keene’s Pulmicort, his asthma medication. The boy was wheezing and looking pasty.

They pulled in to find Mrs. Guild’s green car in the Lusses’ driveway, the sight of which gave Neeva pause. She told Sebastiane to wait for her there, then got out and straightened her slip beneath her dress, going with her key to the side entrance. The door opened without any tone, the house alarm not set. Neeva walked through the perfectly appointed mudroom with built-in cubbies and coat hooks and heated tile floor—a mudroom that had never seen any mud—and pushed through the French doors into the kitchen.

It did not appear that anyone had been in the room since she had left with the children. She stood still inside the doorway and listened with extraordinary attention, holding her breath for as long as she could before exhaling. She heard nothing.

“Hallo?” she called a few times, wondering if Mrs. Guild, with whom she had a largely silent relationship—the housekeeper, Neeva suspected, was a silent racist—would answer. Wondering if Joan—a mother so devoid of natural maternal instinct as to be, for all her lawyerly success, like a child herself—would answer. And knowing, in both cases, that they would not.

Hearing nothing, she crossed to the central island and laid her bag gently down on it, between the sink and the countertop range. She opened the snack cabinet, and quickly, a bit more like a thief than she had imagined, filled a Food Emporium bag with crackers and juice pouches and Smartfood popcorn—stopping once in a while to listen.

After raiding the paneled refrigerator of string cheese and yogurt drinks, she noticed Mr. Luss’s number on the contact sheet taped to the wall near the kitchen phone. A bolt of uncertainty shot through her. What could she say to him? Your wife is ill. She is not right. So I take the children. No. As it was, she barely exchanged words with the man. There was something evil in this magnificent house, and her first and only duty—both as an employee and as a mother herself—was the safety of the children.

She checked the cabinet over the built-in wine cooler, but the box of Pulmicort was empty, just as she had dreaded. She had to go down to the basement pantry. At the top of the curling, carpeted stairs, she paused and pulled from her bag her black enameled crucifix. She descended with it at her side just in case. From the bottom step, the basement appeared very dark for that time of day. She flipped up every switch on the panel and stood listening after the lights came on.

They called it the basement, but it was actually another fully appointed floor of their home. They had installed a home theater downstairs, complete with theater chairs and a reproduction popcorn cart. Another subroom was jammed with toys and game tables; another was the laundry where Mrs. Guild kept up with the family’s clothing and linens. There was also a fourth bathroom, the pantry, and a recently installed temperature-controlled wine cellar. It was European in style, the workers having broken through the basement foundation to create a pure dirt floor.

The heat came rumbling on with a sound like that of somebody kicking the furnace—the actual working guts of the basement were hidden behind a door somewhere—and the sound nearly sent Neeva through the ceiling. She turned back to the stairs, but the boy needed his nebulizer medicine, his color wasn’t good.

She crossed the basement determinedly, and was between two leather theater chairs, halfway to the folding door of the pantry, when she noticed the stuff stacked up against the windows. Why it had seemed so dark down there in the middle of the day: toys and old packing cartons were arranged in a tower up the wall, obscuring the small windows, with old clothes and newspapers snuffing out every ray of the day’s sun.

Neeva stared, wondering who had done this. She hurried to the pantry, finding Keene’s asthma medicine stacked on the same steel-wire shelf as Joan’s vitamins and tubs of candy-colored Tums. She pulled down two long boxes of the plastic vials, ignoring the rest of the food in her haste, rushing away without closing the door.

Starting back across the basement, she noticed that the door to the laundry room was ajar. Something about that door, which was never left open, represented the disruption of normal order that Neeva felt so palpably in this house.

She saw rich and dark dirt stains on the plush carpeting then, spaced almost like footprints. Her eye followed them to the wine cellar door she had to pass in order to reach the stairs. She saw soil smeared on the door handle.

Neeva felt it as she neared the wine cellar door. From that earthen room, a tomblike blackness. A soullessness. And yet—not a coldness. Instead, a contradictory warmth. A heat, lurking and seething.

The door handle began to turn as she rushed past it to the stairs. Neeva, a fifty-three-year-old woman with bad knees, her feet as much kicking at the steps as running up them. She stumbled, steadying herself against the wall with her hand, the crucifix gouging out a small chunk of plaster. Something was behind her, coming up the stairs at her. She yelled in Creole as she emerged into the sunlit first floor, running the length of the long kitchen, grabbing her handbag, knocking over the Food Emporium bag, snacks and drinks crashing to the floor, too scared to turn back.

The sight of her mother running screaming from the house in her ankle-length floral dress and black shoes brought Sebastiane out of her car. “No!” yelled her mother, motioning her back inside. She ran as if she was being chased, but in fact there was no one behind her. Sebastiane dropped back into her seat, alarmed.

“Mama, what happened?”

“Drive!” Neeva yelled, her large chest heaving, her eyes still wild, focused on the open side door.

“Mama,” said Sebastiane, putting the car into reverse. “This is kidnapping. They have laws. Did you call the husband? You said you would call the husband.”

Neeva opened her palm, finding it bloody. She had gripped the beaded crucifix so tightly the crosspiece had cut into her flesh. She let it fall to the floor of the car.

17th Precinct Headquarters, East Fifty-first Street, Manhattan

THE OLD PROFESSOR sat at the very end of the bench inside lockup, as far away as possible from a shirtless, snoring man who had just relieved himself without wishing to trouble anyone else for directions to the toilet in the corner of the room, or even removing his pants.

“Setraykeen … Setarkian … Setrainiak …”

“Here,” he answered, rising and walking toward the remedial reader in the police officer’s uniform by the open tank door. The officer let him out and closed the door behind him.

“Am I being released?” asked Setrakian.

“I guess so. Your son’s here to pick you up.”

“My—”

Setrakian held his tongue. He followed the officer to an unmarked interrogation room. The cop pulled open the door and motioned for him to walk inside.

It took Setrakian a few moments, just long enough for the door to close behind him, to recognize the person on the other side of the bare table as Dr. Ephraim Goodweather of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Next to him was the female doctor who had been with him before. Setrakian smiled appreciatively at their ruse, though he was not surprised by their presence.

Setrakian said, “So it has begun.”

Dark circles—like bruises of fatigue and sleeplessness—hung under Dr. Goodweather’s eyes as he looked the old man up and down. “You want out of here, we can get you out. First I need an explanation. I need information.”

“I can answer many of your questions. But we have lost so much time already. We must begin now—this moment—if we have any chance at all of containing this insidious thing.”

“That’s what I’m talking about,” said Dr. Goodweather, thrusting out one hand rather harshly. “What is this insidious thing?”

“The passengers from the plane,” said Setrakian. “The dead have risen.”

Eph did not know how to answer that. He couldn’t say. He wouldn’t say.

“There is much you will need to let go of, Dr. Goodweather,” said Setrakian. “I understand that you believe you are taking a risk in trusting the word of an old stranger. But, in a sense, I am taking a thousandfold greater risk entrusting this responsibility to you. What we are discussing here is nothing less than the fate of the human race—though I don’t expect you to quite believe that yet, or understand it. You think that you are drafting me into your cause. The truth of the matter is, I am drafting you into mine.”

Knickerbocker Loans and Curios, East 118th Street, Spanish Harlem

Eph put up his EMERGENCY BLOOD DELIVERY windshield placard and parked in a marked loading zone on East 119th Street, following Setrakian and Nora one block south to his corner pawnshop. The doors were gated, the windows shuttered with locked metal plates. Despite the tilted CLOSED sign jammed in the door glass over the store hours, a man in a tattered black peacoat and a high knit hat—like the kind Rastafarians liked to wear, except that he lacked the ropy dreadlocks to fill it out, so it sagged off his head like a collapsed soufflé—stood at the door with a shoe box in his hand, shifting his weight from foot to foot.

Setrakian came out with keys dangling from a chain, busying himself with the locks up and down the door grates, making his gnarled fingers work. “No pawns today,” he said, allowing himself a sidelong glance at the box in the man’s hand.

“Look here.” The man produced a bundle of linen from the shoe box, a dinner napkin he unwrapped to reveal nine or ten utensils. “Good silverware. You buy silver, I know that.”

“I do, yes.” Setrakian, having unlocked the grate, rested the handle of his tall walking stick against his shoulder and selected a knife, weighing it, rubbing the blade with his fingers. After patting his vest pockets, he turned to Eph. “Do you have ten dollars, Doctor?”

In the interest of hurrying this along, Eph reached for his money clip and peeled off a ten-dollar bill. He handed it to the man with the shoe box.

Setrakian then handed the man back his utensils. “You take,” he said. “Not real silver.”

The man accepted the handout gratefully and backed away with the shoe box under his arm. “God bless.”

Setrakian said, entering his shop, “We’ll soon see about that.”

Eph watched his money hustle off down the street, then followed Setrakian inside.

“The lights are right on the wall there,” said the old man, pulling the gate ends to meet again, locking up.

Nora threw all three switches at once, illuminating glass cabinets, display walls, and the entrance where they stood. It was a small corner shop, wedge-shaped, banged into the city block with a wooden hammer. The first word that came to Eph’s mind was “junk.” Lots and lots of junk. Old stereo systems. VCRs and other outdated electronics. A wall display of musical instruments, including a banjo and a Keytar guitarlike keyboard from the 1980s. Religious statues and collectible plates. A couple of turntables and small mixing boards. A locked glass countertop featuring cheap brooches and high-flash, low-quality bling. Racks of clothes, mostly winter coats with fur collars.

So much junk that his heart fell a little. Had he entrusted this precious time to a crazy person?

“Look,” he told the old man, “we have a colleague, we believe he is infected.”

Setrakian passed him, tapping his oversize walking stick. He lifted the hinged counter with his gloved hand and invited Eph and Nora through. “We go up here.”

A back staircase led to a door on the second floor. The old man touched the mezuzah before entering, leaning his tall stick against the wall. It was an aged apartment of low ceilings and worn-out rugs. The furniture hadn’t been moved in perhaps thirty years.

“You are hungry?” Setrakian asked. “Look around, you’ll find something.” Setrakian lifted the top of a fancy pastry container, revealing an open box of Devil Dogs. He lifted one out, tearing open its cellophane wrapper. “Don’t let your energy run down. Keep up your strength. You’ll need it.”

The old man bit into the crème-filled cake on his way to a bedroom to change clothes. Eph looked around the small kitchen, and then at Nora. The place smelled clean despite its cluttered appearance. Nora lifted, from the table with only one chair, a framed black-and-white portrait of a young raven-haired woman in a simple dark dress, posed upon a great rock at an otherwise empty beach, fingers laced over one bare knee, pleasant features arranged in a winning smile. Eph returned to the hallway through which they had entered, looking into the old mirrors hanging from the walls—dozens of them, of all different sizes, time-streaked and imperfect. Old books were stacked along both sides of the floor, narrowing the passageway.

The old man reappeared, having changed into different articles of the same sort of clothing: an old tweed suit with vest, braces, a necktie, and brown leather shoes buffed until thin. He still wore wool tipless gloves over his damaged hands.

“I see you collect mirrors,” Eph said.

“Certain kinds. I find older glass to be most revealing.”

“Are you now ready to tell us what is going on?”

The old man dipped his head gently to one side. “Doctor, this isn’t something one simply tells. It is something that must be revealed.” He moved past Eph to the door through which they had entered. “Please—come with.”

Eph followed him back down the stairs, Nora behind him. They passed the first-floor pawnshop, continuing through another locked door to another curling flight leading down. The old man descended, one angled step at a time, his gnarled hand sliding down the cool iron rail, his voice filling the narrow passageway. “I consider myself a repository of ancient knowledge, of persons dead and books long forgotten. Knowledge accumulated over a life of study.”

Nora said, “When you stopped us outside the morgue, you said a number of things. You indicated that you knew the dead from the airplane were not decomposing normally.”

“Correct.”

“Based upon?”

“My experience.”

Nora was confused. “Experience with other aircraft-related incidents?”

“The fact that they were on an airplane is completely incidental. I have seen this phenomenon before, indeed. In Budapest, in Basra. In Prague and not ten kilometers outside Paris. I have seen it in a tiny fishing village on the banks of the Yellow River. I have seen it at a seven-thousand-feet elevation in the Altai Mountains of Mongolia. And yes, I have seen it on this continent as well. Seen its traces. Usually dismissed as a fluke, or explained away as rabies or schizophrenia, insanity, or, most recently, an occasion of serial murder—”

“Hold on, hold on. You yourself have seen corpses slow to decompose?”

“It is the first stage, yes.”

Eph said, “The first stage.”

The landing curled to an end at a locked door. Setrakian produced a key, separate from the rest, hanging from a chain around his neck. The old man’s crooked fingers worked the key into two padlocks, one large, one small. The door opened inward, hot lights coming on automatically, and they followed him inside the humming basement room, bright and deep.

The first thing to catch Eph’s eye was a wall of battle armor, ranging from full knight’s wear to chain mail to Japanese samurai torso and neck plates, and cruder gear made of woven leather for protecting the neck, chest, and groin. Weapons also: mounted swords and knives, their blades fashioned of bright, cold steel. More modern-looking devices were arranged on an old, low table, their battery packs in chargers. He recognized night-vision goggles and modified nail guns. And more mirrors, mostly pocket-size, arranged so that he could see himself staring in bewilderment at this gallery of … of what?

“The shop”—the old man gestured to the floor above them—“gave me a fair living, but I did not come to this line of business because of an affinity for transistor radios and heirloom jewelry.”

He closed the door behind them, the lights around the door frame going dark. The installed fixtures ran the height and length of the door—purple tubes Eph recognized as ultraviolet lamps—arranged around the door like a force field of light.

To prohibit germs from entering the room? Or to keep something else out?

“No,” he continued, “the reason I chose it as my profession was because it afforded me ready access to an underground market of esoteric items, antiquities, and tomes. Illicit, though not usually illegal. Acquired for my personal collection, and my research.”

Eph looked around again. This looked less like a museum collection than a small arsenal. “Your research?”

“Indeed. I was for many years a professor of Eastern European Literature and Folklore at the University of Vienna.”

Eph appraised him again. He sure dressed like a Viennese professor. “And you retired to become a Harlem pawnbroker-slash-curator?”

“I did not retire. I was made to leave. Disgraced. Certain forces aligned against me. And yet, as I look back now, going underground at that time most certainly saved my life. It was in fact the best thing I could have done.” He turned to face them, folding his hands behind his back, professorially. “This scourge we are now witnessing in its earliest stages has existed for centuries. Over millennia. I suspect, though cannot prove, it goes back to the most ancient of times.”