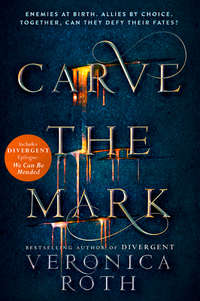

Carve the Mark

“Let that be a lesson to you about sass,” his dad said, leaning over him.

“Sass causes all the blood to rush to your head?” Akos said, blinking innocently up at him.

“Precisely.” Aoseh grinned. “Happy Blooming.”

Akos returned the grin. “You too.”

That night they all stayed up so late Eijeh and Ori both fell asleep upright at the kitchen table. Their mom carried Ori to the living room couch, where she spent a good half of her nights these days, and their dad roused Eijeh. Everybody went one way or another after that, except Akos and his mom. They were always the last two up.

His mom switched the screen on, so the Assembly news feed played at a murmur. There were nine nation-planets in the Assembly, all the biggest or most important ones. Technically each nation-planet was independent, but the Assembly regulated trade, weapons, treaties, and travel, and enforced the laws in unregulated space. The Assembly feed went through one nation-planet after another: water shortage on Tepes, new medical innovation on Othyr, pirates boarded a ship in Pitha’s orbit.

His mom was popping open cans of dried herbs. At first Akos thought she was going to make a calming tonic, to help them both rest, but then she went into the hall closet to get the jar of hushflower, stored on the top shelf, out of the way.

“I thought we’d make tonight’s lesson a special one,” Sifa said. He thought of her that way—by her given name, and not as “Mom”—when she taught him about iceflowers. She’d taken to calling these late-night brewing sessions “lessons” as a joke two seasons ago, but now she sounded serious to Akos. Hard to say, with a mom like his.

“Get out a cutting board and cut some harva root for me,” she said, and she pulled on a pair of gloves. “We’ve used hushflower before, right?”

“In sleeping elixir,” Akos said, and he did as she said, standing on her left with cutting board and knife and dirt-dusted harva root. It was sickly white and covered in a fine layer of fuzz.

“And that recreational concoction,” she added. “I believe I told you it would be useful at parties someday. When you’re older.”

“You did,” Akos said. “You said ‘when you’re older’ then, too.”

Her mouth slanted into her cheek. Most of the time that was the best you could get out of his mom.

“The same ingredients an older version of you might use for recreation, you can also use for poison,” she said, looking grave. “As long as you double the hushflower and halve the harva root. Understand?”

“Why—” Akos started to ask her, but she was already changing the subject.

“So,” she said as she tipped a hushflower petal onto her own cutting board. It was still red, but shriveled, about the length of her thumb. “What is keeping your mind busy tonight?”

“Nothing,” Akos said. “People staring at us at the Blooming, maybe.”

“They are so fascinated by the fate-favored. I would love to tell you they will stop staring someday,” she said with a sigh, “but I’m afraid that you … you will always be stared at.”

He wanted to ask her about that pointed “you,” but he was careful around his mom during their lessons. Ask her the wrong question and she ended the lesson all of a sudden. Ask the right one, and he could find out things he wasn’t supposed to know.

“How about you?” he asked her. “What’s keeping your mind busy, I mean?”

“Ah.” His mom’s chopping was so smooth, the knife tap tap tapping on the board. His was getting better, though he still carved chunks where he didn’t mean to. “Tonight I am plagued by thoughts about the family Noavek.”

Her feet were bare, toes curled under from the cold. The feet of an oracle.

“They are the ruling family of Shotet,” she said. “The land of our enemies.”

The Shotet were a people, not a nation-planet, and they were known to be fierce, brutal. They stained lines into their arms for every life they had taken, and trained even their children in the art of war. And they lived on Thuvhe, the same planet as Akos and his family—though the Shotet didn’t call this planet “Thuvhe,” or themselves “Thuvhesits”—across a huge stretch of feathergrass. The same feathergrass that scratched at the windows of Akos’s family’s house.

His grandmother—his dad’s mom—had died in one of the Shotet invasions, armed only with a bread knife, or so his dad’s stories said. And the city of Hessa still wore the scars of Shotet violence, the names of the lost carved into low stone walls, broken windows patched up instead of replaced, so you could still see the cracks.

Just across the feathergrass. Sometimes they felt close enough to touch.

“The Noavek family is fate-favored, did you know that? Just like you and your siblings are,” Sifa went on. “The oracles didn’t always see fates in that family line, it happened only within my lifetime. And when it did, it gave the Noaveks leverage over the Shotet government, to seize control, which has been in their hands ever since.”

“I didn’t know that could happen. A new family suddenly getting fates, I mean.”

“Well, those of us who are gifted in seeing the future don’t control who gets a fate,” his mom said. “We see hundreds of futures, of possibilities. But a fate is something that happens to a particular person in every single version of the future we see, which is very rare. And those fates determine who the fate-favored families are—not the other way around.”

He’d never thought about it that way. People always talked about the oracles doling out fates like presents to special, important people, but to hear his mom tell it, that was all backward. Fates made certain families important.

“So you’ve seen their fates. The fates of the Noaveks.”

She nodded. “Just the son and the daughter. Ryzek and Cyra. He’s older; she’s your age.”

He’d heard their names before, along with some ridiculous rumors. Stories about them frothing at the mouth, or keeping enemies’ eyeballs in jars, or lines of kill marks from wrist to shoulder. Maybe that one didn’t sound so ridiculous.

“Sometimes it is easy to see why people become what they are,” his mom said softly. “Ryzek and Cyra, children of a tyrant. Their father, Lazmet, child of a woman who murdered her own brothers and sisters. The violence infects each generation.” She bobbed her head, and her body went with it, rocking back and forth. “And I see it. I see all of it.”

Akos grabbed her hand and held on.

“I’m sorry, Akos,” she said, and he wasn’t sure if she was saying sorry for saying too much, or for something else, but it didn’t really matter.

They both stood there for a while, listening to the mutter of the news feed, the darkest night somehow even darker than before.

“HAPPENED IN THE MIDDLE of the night,” Osno said, puffing up his chest. “I had this scrape on my knee, and it started burning. By the time I threw the blankets back, it was gone.”

The classroom had one curved wall and two straight ones. A large furnace packed with burnstones stood in the center, and their teacher always paced around it as she taught, her boots squeaking on the floor. Sometimes Akos counted how many circles she made during one class. It was never a small number.

Around the furnace were metal chairs with glass screens fixed in front of them at an angle, like tabletops. They glowed, ready to show the day’s lesson. But their teacher wasn’t there yet.

“Show us, then,” another classmate, Riha, said. She always wore scarves stitched with maps of Thuvhe, a true patriot, and she never trusted anyone at their word. When someone made a claim, she scrunched up her freckled nose until they proved it.

Osno held a small pocket blade over his thumb and dug in. Blood bubbled from the wound, and even Akos could see, sitting across the room from everyone, that his skin was already starting to close up like a zipper.

Everybody got a currentgift when they got older, after their bodies changed—which meant, judging by how small Akos still was at fourteen seasons old, he wouldn’t be getting his for awhile yet. Sometimes gifts ran in families, and sometimes they didn’t. Sometimes they were useful, and sometimes they weren’t. Osno’s was useful.

“Amazing,” Riha said. “I can’t wait for mine to come. Did you have any idea what it would be?”

Osno was the tallest boy in their class, and he stood close to you when he talked to you so you knew it. The last time he’d talked to Akos had been a season ago, and Osno’s mother had said as she walked away, “For a fate-favored son, he’s not much, is he?”

Osno had said, “He’s nice enough.”

But Akos wasn’t “nice”; that was just what people said about quiet people.

Osno slung his arm over the back of his chair, and flicked his dark hair out of his eyes. “My dad says the better you know yourself, the less surprised you’ll be by your gift.”

Riha’s head bobbed in agreement, her braid sliding up and down her back. Akos made a bet with himself that Riha and Osno would be dating by season’s end.

And then the screen fixed next to the door flickered and switched off. All the lights in the room switched off, too, and the ones that glowed under the door, in the hallway. Whatever Riha had been about to say froze on her lips. Akos heard a loud voice coming from the hall. And the squeal of his own chair as he scooted back.

“Kereseth …!” Osno whispered in warning. But Akos wasn’t sure what was scary about peeking in the hallway. Not like something was going to jump out and bite him.

He opened the door wide enough to let his body through, and leaned into the narrow hallway just outside. The building was circular, like a lot of the buildings in Hessa, with teachers’ offices in the center, classrooms around the circumference, and a hallway separating the two. When the lights were off, it was so dark in the hall he could see only by the emergency lights burning orange at the top of every staircase.

“What’s happening?” He recognized that voice—it was Ori. She moved into the pool of orange light by the east stairwell. Standing in front of her was her aunt Badha, looking more disheveled than he’d ever seen her, pieces of hair hanging around her face, escaped from its knot, and her sweater buttons done up all wrong.

“You are in danger,” Badha said. “It is time for us to do as we have practiced.”

“Why?” Ori demanded. “You come in here, you drag me out of class, you want me to leave everything, everyone—”

“All the fate-favored are in danger, understand? You are exposed. You must go.”

“What about the Kereseths? Aren’t they in danger, too?”

“Not as much as you.” Badha grabbed Ori’s elbow and steered her toward the landing of the east stairwell. Ori’s face was shaded, so Akos couldn’t see her expression. But just before she went around a corner, she turned, hair falling across her face, sweater slipping off her shoulder so he could see her collarbone.

He was pretty sure her eyes found his then, wide and fearful. But it was hard to say. And then someone called Akos’s name.

Cisi was hustling out of one of the center offices. She was in her heavy gray dress, with black boots, and her mouth was taut.

“Come on,” she said. “We’ve been called to the headmaster’s office. Dad is coming for us now, we can wait there.”

“What—” Akos began, but as always, he talked too softly for most people to pay attention.

“Come on.” Cisi pushed through the door she had just closed. Akos’s mind was going in all different directions. Ori was fate-favored. All the lights were off. Their dad was coming to get them. Ori was in danger. He was in danger.

Cisi led the way down the dark hallway. Then: an open door, a lit lantern, Eijeh turning toward them.

The headmaster sat across from him. Akos didn’t know his name; they just called him “Headmaster,” and saw him only when he was giving an announcement or on his way someplace else. Akos didn’t pay him any mind.

“What’s going on?” he asked Eijeh.

“Nobody will say,” Eijeh said, eyes flicking over to the headmaster.

“It is the policy of this school to leave this sort of situation to the parents’ discretion,” the headmaster said. Sometimes kids joked that the headmaster had machine parts instead of flesh, that if you cut him open, wires would come tumbling out. He talked like it, anyway.

“And you can’t say what sort of situation it is?” Eijeh said to him, in much the way their mom would have, if she’d been there. Where is Mom, anyway? Akos thought. Their dad was coming for them, but nobody had said anything about their mom.

“Eijeh,” Cisi said, and her whispered voice steadied Akos, too. It was almost like she spoke into the hum of the current inside him, leveling it just enough. The spell lasted awhile, the headmaster, Eijeh, Cisi, and Akos quiet, waiting.

“It’s getting cold,” Eijeh said eventually, and there was a draft creeping under the door, chilling Akos’s ankles.

“I know. I had to shut off the power,” the headmaster said. “I intend to wait until you are safely on your way before turning it back on.”

“You shut off the power for us? Why?” Cisi said sweetly. The same wheedling voice she used when she wanted to stay up later or have an extra candy for dessert. It didn’t work on their parents, but the headmaster melted like a candle. Akos half expected there to be a puddle of wax spreading under his desk.

“The only way the screens can be turned off during emergency alerts from the Assembly,” the headmaster said softly, “is if the power is shut down.”

“So there was an emergency alert,” Cisi said, still wheedling.

“Yes. It was issued by the Assembly Leader just this morning.”

Eijeh and Akos traded looks. Cisi was smiling, calm, her hands folded over her knees. In this light, with her curly hair framing her face, she was Aoseh’s daughter, pure and simple. Their dad could get what he wanted, too, with smiles and laughs, always soothing people, hearts, situations.

A heavy fist pounded on the headmaster’s door, sparing the wax man from melting further. Akos knew it was his dad because the doorknob fell out at the last knock, the plate that held it fast to the wood cracking right down the middle. He couldn’t control his temper, and his currentgift made that pretty clear. Their dad was always fixing things, but half the time it was because he himself had broken them.

“Sorry,” Aoseh mumbled when he came into the room. He shoved the doorknob back in place and traced the crack with his fingertip. The plate came together a little jagged, but mostly good as new. Their mom insisted he didn’t always fix things right, and they had the uneven dinner plates and jagged mug handles to prove it.

“Mr. Kereseth,” the headmaster began.

“Thank you, Headmaster, for reacting so quickly,” their dad said to him. He wasn’t smiling even a little. More than the dark hallways or Ori’s shouting aunt or Cisi’s pressed-line mouth, his serious face scared Akos. Their dad was always smiling, even when the situation didn’t call for it. Their mom called it his very best armor.

“Come on, Small Child, Smaller Child, Smallest Child,” Aoseh said halfheartedly. “Let’s go home.”

They were up on their feet and marching toward the school entrance as soon as he said “home.” They went straight to the coatracks to search the identical gray furballs for the ones with their names stitched into the collars: Kereseth, Kereseth, Kereseth. Cisi and Akos confused theirs for a tick and had to switch, Akos’s just a little too small for her arms, hers just a little too long for his short frame.

The floater waited just outside, the door still thrown open. It was a little bigger than most, still squat and circular, the dark metal outsides streaked with dirt. The news feed, usually playing in a stream of words around the inside of the floater, wasn’t on. The nav screen wasn’t on, either, so it was just Aoseh poking at buttons and levers and controls without the floater telling them what he was doing. They didn’t buckle themselves in; Akos felt like it was stupid to waste the time.

“Dad,” Eijeh started.

“The Assembly took it upon itself to announce the fates of the favored lines this morning,” their dad said. “The oracles shared the fates with the Assembly seasons ago, in confidence, as a gesture of trust. Usually a person’s fate isn’t made public until after they die, known only to them and their families, but now …” His eyes raked over each of them in turn. “Now everyone knows your fates.”

“What are they?” Akos asked in a whisper, just as Cisi asked, “Why is that dangerous?”

Dad answered her, not him. “It’s not dangerous for everyone with a fate. But some are more … revealing than others.”

Akos thought of Ori’s aunt dragging her by the elbow to the stairwell. You are exposed. You must go.

Ori had a fate—a dangerous one. But as far as Akos could remember, there wasn’t any “Rednalis” family in the list of favored lines. It must not have been her real name.

“What are our fates?” Eijeh asked, and Akos envied him for his loud, clear voice. Sometimes when they stayed up later than they were supposed to, Eijeh tried to whisper, but one of their parents always ended up at their door to shush them before long. Not like Akos; he kept secrets closer than his own skin, which was why he wasn’t telling the others about Ori just yet.

The floater zoomed over the iceflower fields their dad managed. They stretched out for miles in every direction, divided by low wire fences: yellow jealousy flowers, white purities, green harva vines, brown sendes leaves, and last, protected by a cage of wire with current running through it, red hushflower. Before they put up the wire cage, people used to take their lives by running straight into the hushflower fields and dying there among the bright petals, the poison putting them to sleepy death in a few breaths. It didn’t seem like a bad way to go, really, Akos thought. Drifting off with flowers all around you and the white sky above.

“I’ll tell you when we’re safe and sound,” their dad said, trying to sound cheery.

“Where’s Mom?” Akos said, and this time, Aoseh heard him.

“Your mother …” Aoseh clenched his teeth, and a huge gash opened up in the seat under him, like the top of a loaf of bread splitting in the oven. He swore, and ran his hand over it to mend it. Akos blinked at him, afraid. What had gotten him so angry?

“I don’t know where your mother is,” he finished. “I’m sure she’s fine.”

“She didn’t warn you about this?” Akos said.

“Maybe she didn’t know,” Cisi whispered.

But they all knew how wrong that was. Sifa always, always knew.

“Your mother has her reasons for everything she does. Sometimes we don’t get to know them,” Aoseh said, a little calmer now. “But we have to trust her, even when it’s difficult.”

Akos wasn’t sure their dad believed it. Like maybe he was just saying it to remind himself.

Aoseh guided the floater down in their front lawn, crushing the tufts and speckled stalks of feathergrass under them. Behind their house, the feathergrass went on as far as Akos could see. Strange things sometimes happened to people in the grasses. They heard whispers, or they saw dark shapes among the stems; they waded through the snow, away from the path, and were swallowed by the earth. Every so often they heard stories about it, or someone spotted a full skeleton from their floater. Living as close to the tall grass as Akos did, he’d gotten used to ignoring the faces that surged toward him from all directions, whispering his name. Sometimes they were crisp enough to identify: dead grandparents; his mom or dad with warped, corpse faces; kids who were mean to him at school, taunting.

But when Akos got out of the floater and reached up to touch the tufts above him, he realized, with a start, that he wasn’t seeing or hearing anything anymore.

He stopped, and hunted the grasses for a sign of the hallucinations anywhere. But there weren’t any.

“Akos!” Eijeh hissed.

Strange.

He chased Eijeh’s heels to the front door. Aoseh unlocked it, and they all piled into the foyer to take off their coats. As he breathed the inside air, though, Akos realized something didn’t smell right. Their house always smelled spicy, like the breakfast bread their dad liked to make in the colder months, but now it smelled like engine grease and sweat. Akos’s insides were a rope, twisting tight.

“Dad,” he said as Aoseh turned on the lights with the touch of a button.

Eijeh yelled. Cisi choked. And Akos went stock-still.

There were three men standing in their living room. One was tall and slim, one taller and broad, and the third, short and thick. All three wore armor that shone in the yellowish burnstone light, so dark it almost looked black, except it was actually dark, dark blue. They held currentblades, the metal clasped in their fists and the black tendrils of current wrapping around their hands, binding the weapons to them. Akos had seen blades like that before, but only in the hands of the soldiers that patrolled Hessa. They had no need of currentblades in their house, the house of a farmer and an oracle.

Akos knew it without really knowing it: These men were Shotet. Enemies of Thuvhe, enemies of theirs. People like this were responsible for every candle lit in the memorial of the Shotet invasion; they had scarred Hessa’s buildings, busted its glass so it showed fractured images; they had culled the bravest, the strongest, the fiercest, and left their families to weeping. Akos’s grandmother and her bread knife among them, so said their dad.

“What are you doing here?” Aoseh said, tense. The living room looked untouched, the cushions still arranged around the low table, the fur blanket curled by the fire where Cisi had left it when she was reading. The fire was embers, still glowing, and the air was cold. Their dad took a wider stance, so his body covered all three of them.

“No woman,” one of the men said to one of the others. “Wonder where she is?”

“Oracle,” one of the others replied. “Not an easy one to catch.”

“I know you speak our language,” Aoseh said, sterner this time. “Stop jabbering away like you don’t understand me.”

Akos frowned. Hadn’t his dad heard them talking about their mom?

“He is quite demanding, this one,” the tallest one said. He had golden eyes, Akos noticed, like melted metal. “What is the name again?”

“Aoseh,” the shortest one said. He had scars all over his face, little slashes going every direction. The skin around the longest one, next to his eye, was puckered. Their dad’s name sounded clumsy in his mouth.

“Aoseh Kereseth,” the golden-eyed one said, and this time he sounded … different. Like he was suddenly speaking with a thick accent. Only he hadn’t had one before, so how could that be? “My name is Vas Kuzar.”

“I know who you are,” Aoseh said. “I don’t live with my head in a hole.”

“Grab him,” the man called Vas said, and the shortest one lunged at their dad. Cisi and Akos jumped back as their dad and the Shotet soldier scuffled, their arms locked together. Aoseh’s teeth gritted. The mirror in the living room shattered, the pieces flying everywhere, and then the picture frame on the mantel, the one from their parents’ wedding day, cracked in half. But still the Shotet soldier got a hold on Aoseh, wrestling him into the living room and leaving the three of them, Eijeh, Cisi, and Akos, exposed.

The shortest soldier forced their dad to his knees, and pointed a currentblade at his throat.

“Make sure the children don’t leave,” Vas said to the slim one. Just then Akos remembered the door behind him. He seized the knob, twisted it. But by the time he was pulling it, a rough hand had closed around his shoulder, and the Shotet lifted him up with one arm. Akos’s shoulder ached; he kicked the man hard in the leg. The Shotet just laughed.