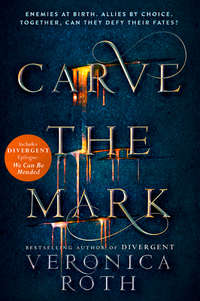

Carve the Mark

“Not everything that is effective must be done in public,” Father said casually as he flipped the switch to turn the amplifiers off again. “The guards will whisper of what you are willing to do to those who speak out against you, and the ones they whisper to will whisper also, and then your strength and power will be known all throughout Shotet.”

A scream was building inside me, and I held it in my throat like a piece of food that was too big to swallow.

The small dark room faded.

I stood on a bright street teeming with people. I was at my mother’s hip, my arm wrapped around her leg. Dust rose into the air around us—in the capital city of the nation-planet Zold, the dully named Zoldia City, which we had visited on my first sojourn, everything was coated in a fine layer of gray dust at that time of year. It came not from rock or earth, as I had assumed, but from a vast field of flowers that grew east of here and disintegrated in the strong seasonal wind.

I knew this place, this moment. It was one of my favorite memories of my mother and me.

My mother bent her head to the man who had met her in the street, her hand skimming my hair.

“Thank you, Your Grace, for hosting our scavenge so graciously,” my mother said to him. “I will do my best to ensure that we take only what you no longer need.”

“I would appreciate that. There were reports during the last scavenge of Shotet soldiers looting. Hospitals, no less,” the man responded gruffly. His skin was bright with the dust, and almost seemed to sparkle in the sunlight. I stared up at him with wonder. He wore a long gray robe, almost like he wanted to resemble a statue.

“The conduct of those soldiers was appalling, and punished severely,” my mother said firmly. She turned to me. “Cyra, my dear, this is the leader of the capital city of Zold. Your Grace, this is my daughter, Cyra.”

“I like your dust,” I said. “Does it get in your eyes?”

The man seemed to soften a little as he replied, “Constantly. When we are not hosting visitors, we wear goggles.”

He took a pair from his pocket and offered them to me. They were big, with pale green glass for lenses. I tried them on, and they dropped straight from my face to my neck, so I had to hold them up with one hand. My mother laughed—light, easy—and the man joined in.

“We will do our best to honor your tradition,” the man said to my mother. “Though I confess we do not understand it.”

“Well, we seek renewal above all else,” she said. “And we find what is to be made new in what has been discarded. Nothing worthwhile should ever be wasted. Surely we can agree on that.”

And then her words were playing backward, and the goggles were lifting up to my eyes, then over my head, and into the man’s hand again. It was my first scavenge, and it was unwinding, unraveling in my mind. After the memory played backward, it was gone.

I was back in my bedroom, with the figurines surrounding me, and I knew that I had had a first sojourn, and that we had met the leader of Zoldia City, but I could no longer bring the images to mind. In their place was the prisoner with the cord around his throat, and Father’s low tones in my ear.

Ryz had traded one of his memories for one of mine.

I had seen him do it before, once to Vas, his friend and steward, and once to my mother. Each time he had come back from a meeting with my father looking like he had been shredded to pieces. Then he had put a hand on his oldest friend, or on our mother, and a moment later, he had straightened, dry-eyed, looking stronger than before. And they had looked … emptier, somehow. Like they had lost something.

“Cyra,” Ryz said. Tears stained his cheeks. “It’s only fair. It’s only fair that we should share this burden.”

He reached for me again. Something deep inside me burned. As his hand found my cheek, dark, inky veins spread beneath my skin like many-legged insects, like webs of shadow. They moved, crawling up my arms, bringing heat to my face. And pain.

I screamed, louder than I had ever screamed in my life, and Ryz’s voice joined mine, almost in harmony. The dark veins had brought pain; the darkness was pain, and I was made of it, I was pain itself.

He yanked his hand away, but the skin-shadows and the agony stayed, my currentgift beckoned forward too soon.

My mother ran into the room, her shirt only half buttoned, her face dripping from washing without drying. She saw the black stains on my skin and ran to me, setting her hands on my arms for just a moment before yanking them back, flinching. She had felt the pain, too. I screamed again, and clawed at the black webs with my fingernails.

My mother had to drug me to calm me down.

Never one to bear pain well, Ryz didn’t lay a hand on me again, not if he could help it. And neither did anyone else.

“WHERE ARE WE GOING?”

I chased my mother through the polished hallways, the floors gleaming with my dark-streaked reflection. Ahead of me, she was holding her skirts, her spine straight. She always looked elegant, my mother. She wore dresses with plates from an Armored One built into the bodices, draped with fabric so they still looked light as air. She knew how to draw a perfect line on her eyelid that made it look like she had long eyelashes at each corner. I had tried to do that once, but I hadn’t been able to keep my hand steady long enough to draw the line, and I had to stop every few seconds to gasp through pain. Now I favored simplicity over elegance, loose shifts and shoes without laces, pants that didn’t require buttoning and sweaters that covered most of my skin. I was almost nine seasons old, and already stripped of frivolities.

The pain was just part of life now. Simple tasks took twice as long because I had to pause for breath. People no longer touched me, so I had to do everything myself. I tried feeble medicines and potions from other planets in the vain hope they would suppress my gift, and they always made me sick.

“Quiet,” my mother said, touching her finger to her lips. She opened a door, and we walked onto the landing pad on the roof of Noavek manor. There was a transport vessel perched there like a bird resting midflight, its loading doors open for us. She looked around once, then grabbed my shoulder—covered with fabric, so I didn’t hurt her—and pulled me toward the ship.

Once we were inside, she sat me down in one of the flight seats and pulled the straps tight across my lap and chest.

“We’re going to see someone who might be able to help you,” she said.

The sign on the specialist’s door said Dr. Dax Fadlan, but he told me to call him Dax. I called him Dr. Fadlan. My parents had raised me to show respect to people who had power over me.

My mother was tall, with a long neck that tilted forward, like she was always bowing. Right now the tendons stood out from her throat, and I could see her pulse there, fluttering just at the surface of her skin.

Dr. Fadlan’s eyes kept drifting to my mother’s arm. She had her kill marks exposed, and even they looked beautiful, not brutal, each line straight, all at even intervals. I didn’t think Dr. Fadlan, an Othyrian, saw many Shotet in his offices.

It was an odd place. When I arrived, they put me in a room with a bunch of unfamiliar toys, and I played with some of the small figurines the way Ryzek and I had at home, when we still played together: I lined them up like an army, and marched them into battle against the giant, squashy animal in the corner of the room. After about an hour Dr. Fadlan had told me to come out, that he had finished his assessment. Only I hadn’t done anything yet.

“Eight seasons is a little young, of course, but Cyra isn’t the youngest child I’ve seen develop a gift,” Dr. Fadlan said to my mother. The pain surged, and I tried to breathe through it as they told Shotet soldiers to when they had to get a wound stitched and there was no time for a numbing agent. I had seen recordings of it. “Usually it happens in extreme circumstances, as a protective measure. Do you have any idea what those circumstances might have been? They may give us an insight into why this particular gift developed.”

“I told you,” my mother said. “I don’t know.”

She was lying. I had told her what Ryzek did to me, but I knew better than to contradict her now. When my mother lied, it was always for a good reason.

“Well, I’m sorry to tell you that Cyra is not simply growing into her gift,” Dr. Fadlan said. “This appears to be its full manifestation. And the implications of that are somewhat disturbing.”

“What do you mean?” I didn’t think my mother could sit up any straighter, and then she did.

“The current flows through every one of us,” Dr. Fadlan said gently. “And like liquid metal flowing into a mold, it takes a different shape in each of us, showing itself in a different way. As a person develops, those changes can alter the mold the current flows through, so the gift can also shift—but people don’t generally change on such a fundamental level.”

Dr. Fadlan had an unmarked arm, and he did not speak the revelatory tongue. There were deep lines around his mouth and eyes, and they grew even deeper as he looked at me. His skin was the same shade as my mother’s, however, suggesting a common lineage. Many Shotet had mixed blood, so it wasn’t surprising—my own skin was a medium brown, almost golden in certain lights.

“That your daughter’s gift causes her to invite pain into herself, and project pain into others, suggests something about what’s going on inside her,” Dr. Fadlan said. “It would take further study to know exactly what that is. But a cursory assessment says that on some level, she feels she deserves it. And she feels others deserve it as well.”

“You’re saying this gift is my daughter’s fault?” The pulse in my mother’s throat moved faster. “That she wants to be this way?”

Dr. Fadlan leaned forward and looked directly at me. “Cyra, the gift comes from you. If you change, the gift will, too.”

My mother stood. “She is a child. This is not her fault, and it’s not what she wants for herself. I’m sorry that we wasted our time here. Cyra.”

She held out her gloved hand, and wincing, I took it. I wasn’t used to seeing her so agitated. It made all the shadows under my skin move faster.

“As you can see,” Dr. Fadlan said, “it gets worse when she’s emotional.”

“Quiet,” my mother snapped. “I won’t have you poisoning her mind any more than you already have.”

“With a family like yours, my fear is that she has already seen too much for her mind to be saved,” he retorted as we left the room.

My mother rushed us through the hallways to the loading bay. By the time we reached the landing pad, there were Othyrian soldiers surrounding our vessel. Their weapons looked feeble to me, slim rods with dark current wrapped around them, set to stun instead of kill. Their armor, too, was pathetic, made of pillowed synthetic material that left their sides exposed.

My mother ordered me into the ship, and paused to speak with one of them. I dawdled on my way to the door to hear what they said.

“We are here to escort you off-world,” the soldier said.

“I am the wife of the sovereign of Shotet. You should address me as ‘my lady,’” my mother snapped.

“My apologies, ma’am, but the Assembly of Nine Planets recognizes no Shotet nation, and therefore no sovereign. If you leave the planet immediately, we will cause you no trouble.”

“No Shotet nation.” My mother laughed a little. “A time will come when you will wish you hadn’t said that.”

She clutched her skirts to lift them, and marched into the ship. I scrambled inside and found my seat, and she sat beside me. The door closed behind us, and ahead of us, the pilot gave the signal for liftoff. This time I pulled the straps across my own chest and lap, because my mother’s hands were shaking too badly to do it for me.

I didn’t know it at the time, of course, but that was the last season I had with her. She passed away after the next sojourn, when I was nine.

We burned a pyre for her in the center of the city of Voa, but the sojourn ship carried her ashes into space. As our family grieved, the people of Shotet grieved along with us.

Ylira Noavek will sojourn forever after the current, the priest said as the ashes launched behind us. It will carry her on a path of wonder.

For seasons afterward, I couldn’t even speak her name. After all, it was my fault she was gone.

THE FIRST TIME I saw the Kereseth brothers, it was from the servants’ passageway that ran alongside the Weapons Hall. I was several seasons older, fast approaching adulthood.

My father had joined my mother in the afterlife just a few seasons prior, killed in an attack during a sojourn. My brother, Ryzek, was now walking the path our father had set for him, the path toward Shotet legitimacy. Maybe even Shotet dominance.

My former tutor, Otega, had been the first to tell me about the Kereseths, because the servants in our house were whispering the story over the pots and pans in the kitchen, and she always told me of the servants’ whispers.

“They were taken by your brother’s steward, Vas,” she said to me as she checked my essay for grammatical errors. She still taught me literature and science, but I had outstripped her in my other subjects, and now studied on my own as she returned to managing our kitchens.

“I thought Ryzek sent soldiers to capture the oracle. The old one,” I said.

“He did,” Otega said. “But the oracle took her life in the struggle, to avoid capture. In any case, Vas and his men were tasked to go after the Kereseth brothers instead. Vas dragged them across the Divide kicking and screaming, to hear the others tell of it. But the younger one—Akos—escaped his bonds somehow, stole a blade, and turned it against one of Vas’s soldiers. Killed him.”

“Which one?” I asked. I knew the men Vas traveled with. Knew how one liked candy, another had a weak left shoulder, and yet another had trained a pet bird to eat treats from his mouth. It was good to know such things about people. Just in case.

“Kalmev Radix.”

The candy lover, then.

I raised my eyebrows. Kalmev Radix, one of my brother’s trusted elite, had been killed by a Thuvhesit boy? That was not an honorable death.

“Why were the brothers taken?” I asked her.

“Their fates.” Otega waggled her eyebrows. “Or so the story goes. And since their fates are, evidently, unknown by all but Ryzek, it is quite the story.”

I didn’t know the fates of the Kereseth boys, or any but mine and Ryzek’s, though they had been broadcast a few days ago on the Assembly news feed. Ryzek had cut the news feed within moments of the Assembly Leader coming on screen. The Assembly Leader had given the announcement in Othyrian, and though the speaking and learning of all languages but Shotet had been banned in our country for over ten seasons, it was still better to be safe.

My father had told me my own fate after my currentgift manifested, with little ceremony: The second child of the family Noavek will cross the Divide. A strange fate for a favored daughter, but only because it was so dull.

I didn’t wander the servants’ passages that often anymore—there were things happening in this house I didn’t want to see—but to catch a glimpse of the kidnapped Kereseths … well. I had to make an exception.

All I knew about the Thuvhesit people—apart from the fact that they were our enemies—was they had thin skin, easy to pierce with a blade, and they overindulged in iceflowers, the lifeblood of their economy. I had learned their language at my mother’s insistence—the Shotet elite were exempt from my father’s prohibitions against language learning, of course—and it was hard on my tongue, which was used to harsh, strong Shotet sounds instead of the hushed, quick Thuvhesit ones.

I knew Ryzek would have the Kereseths taken to the Weapons Hall, so I crouched in the shadows and slid the wall panel back, leaving myself just a crack to see through, when I heard footsteps.

The room was like all the others in Noavek manor, the walls and floor made of dark wood so polished it looked like it was coated in a film of ice. Dangling from the distant ceiling was an elaborate chandelier made of glass globes and twisted metal. Tiny fenzu insects fluttered inside it, casting an eerie, shifting light over the room. The space was almost empty, all the floor cushions—balanced on low wooden stands, for comfort—gathering dust, so their cream color turned gray. My parents had hosted parties in here, but Ryzek used it only for people he meant to intimidate.

I saw Vas, my brother’s steward, before anyone else. The long side of his hair was greasy and limp, the shaved side red with razor burn. Beside him shuffled a boy, much smaller than I was, his skin a patchwork of bruises. He was narrow through the shoulders, spare and short. He had fair skin, and a kind of wary tension in his body, like he was bracing himself.

Muffled sobs came from behind him, where a second boy, with dense, curly hair, stumbled along. He was taller and broader than the first Kereseth, but cowering, so he almost appeared smaller.

These were the Kereseth brothers, the fate-favored children of their generation. Not an impressive sight.

My brother waited for them across the room, his long body draped over the steps that led to a raised platform. His chest was covered with armor, but his arms were bare, displaying a line of kill marks that went all the way up the back of his forearm. They had been deaths ordered by my father, to counteract any rumors about my brother’s weakness that might have spread among the lower classes. He held a small currentblade in his right hand, and every few seconds he spun it in his palm, always catching it by the handle. In the bluish light, his skin was so pale he looked almost like a corpse.

He smiled when he saw his Thuvhesit captives, his teeth showing. He could be handsome when he smiled, my brother, even if it meant he was about to kill you.

He leaned back, balancing on his elbows, and cocked his head.

“My, my,” he said. His voice was deep and scratchy, like he had just spent the night screaming at the top of his lungs.

“This is the one I’ve heard so many stories about?” Ryzek nodded to the bruised Kereseth boy. He spoke Thuvhesit crisply. “The Thuvhesit boy who earned a mark before we even got him on a ship?” He laughed.

I squinted at the bruised one’s arm. There was a deep cut on the outside of his arm next to the elbow, and a streak of blood that had run between his knuckles and dried there. A kill mark, unfinished. A very new one, belonging, if the rumors were true, to Kalmev Radix. This was Akos, then, and the snuffling one was Eijeh.

“Akos Kereseth, the third child of the family Kereseth.” Ryzek stood, spinning his knife on his palm, and walked down the steps. He dwarfed even Vas. He was like a regular-size man stretched taller and thinner than he was supposed to be, his shoulders and hips too narrow to bear his own height.

I was tall, too, but that was where my physical similarities with my brother ended. It wasn’t uncommon for Shotet siblings to look dissimilar, given how blended our blood was, but we were more distinct than most.

The boy—Akos—lifted his eyes to Ryzek’s. I had first seen the name “Akos” in a Shotet history book. It had belonged to a religious leader, a cleric who had taken his life rather than dishonor the current by holding a currentblade. So this Thuvhesit boy had a Shotet name. Had his parents simply forgotten its origins? Or did they want to honor some long-forgotten Shotet blood?

“Why are we here?” Akos said hoarsely, in Shotet.

Ryzek only smiled further and responded in the same language. “I see the rumors are true—you can speak the revelatory tongue. How fascinating. I wonder how you came by your Shotet blood?” He prodded the corner of Akos’s eye, at the bruise there, making him wince. “You received quite a punishment for your murder of one of my soldiers, I see. I take it your rib cage is suffering damage.”

Ryzek flinched a little as he spoke. Only someone who had known him as long as I had could have seen it, I was certain. Ryzek hated to watch pain, not out of empathy for the person suffering it, but because he didn’t like to be reminded that pain existed, that he was as vulnerable to it as anyone else.

“Almost had to carry him here,” Vas said. “Definitely had to carry him onto the ship.”

“Usually you would not survive a defiant gesture like killing one of my soldiers,” Ryzek said, speaking down to Akos like he was a child. “But your fate is to die serving the family Noavek, to die serving me, and I’d rather get a few seasons out of you first, you see.”

Akos had been tense since I laid eyes on him. As I watched, it was as if all the hardness in him melted away, leaving him looking as vulnerable as a small child. His fingers were curled, but not into fists. Passively, like he was sleeping.

I guess he hadn’t known his fate.

“That isn’t true,” Akos said, like he was waiting for Ryzek to soothe away the fear. I pressed a sharp pain from my stomach with a palm.

“Oh, I assure you that it is. Would you like me to read from the transcript of the announcement?” Ryzek took a square of paper from his back pocket—he had come to this meeting prepared to wreak emotional havoc, apparently—and unfolded it. Akos was trembling.

“‘The third child of the family Kereseth,’” Ryzek read, in Othyrian, the most commonly spoken language in the galaxy. Somehow hearing the fate in the language in which it had been announced made it sound more real to me. I wondered if Akos, shuddering at each syllable, felt the same. “‘Will die in service to the family Noavek.’”

Ryzek let the paper drop to the floor. Akos grabbed it so roughly it almost tore. He stayed crouched as he read the words—again and again—as if rereading them would change them. As if his death, and his service to our family, were not preordained.

“It won’t happen,” Akos said, harder this time, as he stood. “I would rather … I would rather die than—”

“Oh, I don’t think that’s true,” Ryzek said, lowering his voice to a near whisper. He bent close to Akos’s face. Akos’s fingers tore holes in the paper, though he was otherwise still. “I know what people look like when they want to die. I’ve brought many of them to that point myself. And you are still very much desperate to survive.”

Akos took a breath, and his eyes found my brother’s with new steadiness. “My brother has nothing to do with you. You have no claim to him. Let him go, and I … I won’t give you any trouble.”

“You seem to have made several incorrect assumptions about what you and your brother are doing here,” Ryzek said. “We did not, as you have assumed, cross the Divide just to speed along your fate. Your brother is not collateral damage; you are. We went in search of him.”

“You didn’t cross the Divide,” Akos snapped. “You just sat here and let your lackeys do it all for you.”

Ryzek turned and climbed to the top of the platform. The wall above it was covered with weapons of all shapes and sizes, most of them currentblades as long as my arm. He selected a large, thick knife with a sturdy handle, like a meat cleaver.

“Your brother has a particular destiny,” Ryzek said, looking the knife over. “I assume, since you did not know your own fate, that you don’t know his, either?”