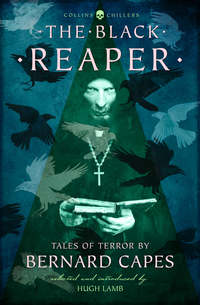

The Black Reaper: Tales of Terror by Bernard Capes

‘Give us the story, Jack,’ said the ‘bones’, whose agued shins were extemporising a rattle on their own account before the fire.

‘Well, I don’t mind,’ said the fat man. ‘It’s seasonable; and I’m seasonable, like the blessed plum-pudden, I am; and the more burnt brandy you set about me, the richer and headier I’ll go down.’

‘You’d be a jolly old pudden to digest,’ said the piccolo.

‘You blow your aggrawation into your pipe and sealing-wax the stops,’ said his friend.

He drew critically at his ‘churchwarden’ a moment or so, leaned forward, emptied his glass into his capacious receptacles, and, giving his stomach a shift, as if to accommodate it to its new burden, proceeded as follows:

‘Music and malt is my nat’ral inheritance. My grandfather blew his “dog’s-nose”, and drank his clarinet like a artist; and my father—’

‘What did you say your grandfather did?’ asked the piccolo.

‘He played the clarinet.’

‘You said he blew his “dog’s-nose”.’

‘Don’t be an ass, Fred!’ said the banjo, aggrieved. ‘How the blazes could a man blow his dog’s nose, unless he muzzled it with a handkercher, and then twisted its tail? He played the clarinet, I say; and my father played the musical glasses, which was a form of harmony pertiklerly genial to him. Amongst us we’ve piped out a good long century – ah! we have, for all I look sich a babby bursting on sops and spoon meat.’

‘What!’ said the little man by the door. ‘You don’t include them cockt hatses in your experience?’

‘My grandfather wore ’em, sir. He wore a play-actin’ coat, too, and buckles to his shoes, when he’d got any; and he and a friend or two made a permanency of “waits” (only they called ’em according to the season), and got their profit goin’ from house to house, principally in the country, and discoursin’ music at the low rate of whatever they could get for it.’

‘Ain’t you comin’ to the ghost, Jack?’ said the little man hungrily.

‘All in course, sir. Well, gentlemen, it was hard times pretty often with my grandfather and his friends, as you may suppose; and never so much as when they had to trudge it across country, with the nor’-easter buzzin’ in their teeth and the snow piled on their cockt hats like lemon sponge on entry dishes. The rewards, I’ve heard him say – for he lived to be ninety, nevertheless – was poor compensation for the drifts, and the influenza, and the broken chilblains; but now and again they’d get a fair skinful of liquor from a jolly squire, as ’d set ’em up like boggarts mended wi’ new broomsticks.’

‘Ho-haw!’ broke in a hurdle-maker in a corner; and then, regretting the publicity of his merriment, put his fingers bashfully to his stubble lips.

‘Now,’ said the banjo, ‘it’s of a pertikler night and a pertikler skinful that I’m a-going to tell you; and that night fell dark, and that skinful were took a hundred years ago this December, as I’m a Jack-pudden!’

He paused for a moment for effect, before he went on:

‘They were down in the sou’-west country, which they little knew; and were anighing Winchester city, or should ’a’ been. But they got muzzed on the ungodly downs, and before they guessed, they was off the track. My good hat! there they was, as lost in the snow as three nut-shells a-sinkin’ into a hasty pudden. Well, they wandered round; pretty confident at first, but getting madder and madder as every sense of their bearings slipped from them. And the bitter cold took their vitals, so they saw nothing but a great winding sheet stretched abroad for to wrap their dead carcasses in.

‘At last my grandfather he stopt and pulled hisself together with an awful face, and says he: “We’re Christmas pie for the carrying-on crows if we don’t prove ourselves human. Let’s fetch our pipes and blow our trouble into ’em.” So they stood together, like as if they were before a house, and they played “Kate of Aberdare” mighty dismal and flat, for their fingers froze to the keys.

‘Now, I tell you, they hadn’t climbed over the first stave, when there come a skirl of wind and spindrift of snow as almost took them off their feet; and, on the going down of it, Jem Sloke, as played the hautboy, dropped the reed from his mouth, and called out, “Sakes alive! if we fools ain’t been standin’ outside a gentleman’s gate all the time, and not knowin’ it!”

‘You might ’a’ knocked the three of ’em down wi’ a barley straw, as they stared and stared, and then fell into a low, enjoyin’ laugh. For they was standin’ not six fut from a tall iron gate in a stone wall, and behind these was a great house showin’ out dim, with the winders all lighted up.

‘“Lord!” chuckled my grandfather, “to think o’ the tricks o’ this vagarious country! But, as we’re here, we’ll go on and give ’em a taste of our quality.”

‘They put new heart into the next movement, as you may guess; and they hadn’t fair started on it, when the door of the house swung open, and down the shaft of light that shot out as far as the gate there come a smiling young gal, with a tray of glasses in her hands.

‘Now she come to the bars; and she took and put a glass through, not sayin’ nothin’, but invitin’ someone to drink with a silent laugh.

‘Did anyone take that glass? Of course he did, you’ll be thinkin’; and you’ll be thinkin’ wrong. Not a man of the three moved. They was struck like as stone, and their lips was gone the colour of sloe berries. Not a man took the glass. For why? The moment the gal presented it, each saw the face of a thing lookin’ out of the winder over the porch, and the face was hidjus beyond words, and the shadder of it, with the light behind, stretched out and reached to the gal, and made her hidjus, too.

‘At last my grandfather give a groan and put out his hand; and, as he did it, the face went, and the gal was beautiful to see agen.

‘“Death and the devil!” said he. “It’s one or both, either way; and I prefer ’em hot to cold!”

‘He drank off half the glass, smacked his lips, and stood staring a moment.

‘“Dear, dear!” said the gal, in a voice like falling water, “you’ve drunk blood, sir!”

‘My grandfather gave a yell, slapped the rest of the liquor in the faces of his friends, and threw the cup agen the bars. It broke with a noise like thunder, and at that he up’d with his hands and fell full length into the snow.’

There was a pause. The little man by the door was twisting nervously in his chair.

‘He came to – of course, he came to?’ said he at length.

‘He come to,’ said the banjo solemnly, ‘in the bitter break of dawn; that is, he come to as much of hisself as he ever was after. He give a squiggle and lifted his head; and there was he and his friends a-lyin’ on the snow of the high downs.’

‘And the house and the gal?’

‘Narry a sign of either, sir, but just the sky and the white stretch; and one other thing.’

‘And what was that?’

‘A stain of red sunk in where the cup had spilt.’

There was a second pause, and the banjo blew into the bowl of his pipe.

‘They cleared out of that neighbourhood double quick, you’ll bet,’ said he. ‘But my grandfather was never the same man agen. His face took purple, while his friends’ only remained splashed with red, same as birth marks; and, I tell you, if ever he ventur’d upon “Kate of Aberdare”, his cheeks swelled up to the reed of his clarinet, like as a blue plum on a stalk. And forty years after, he died of what they call solution of blood to the brain.’

‘And you can’t have better proof than that,’ said the little man.

‘That’s what I say,’ said the banjo. ‘Next player, gentlemen, please.’

THE THING IN THE FOREST

Into the snow-locked forests of Upper Hungary steal wolves in winter; but there is a footfall worse than theirs to knock upon the heart of the lonely traveller.

One December evening Elspet, the young, newly wedded wife of the woodman Stefan, came hurrying over the lower slopes of the White Mountains from the town where she had been all day marketing. She carried a basket with provisions on her arm; her plump cheeks were like a couple of cold apples; her breath spoke short, but more from nervousness than exhaustion. It was nearing dusk, and she was glad to see the little lonely church in the hollow below, the hub, as it were, of many radiating paths through the trees, one of which was the road to her own warm cottage yet a half-mile away.

She paused a moment at the foot of the slope, undecided about entering the little chill, silent building and making her plea for protection to the great battered stone image of Our Lady of Succour which stood within by the confessional box; but the stillness and the growing darkness decided her, and she went on. A spark of fire glowing through the presbytery window seemed to repel rather than attract her, and she was glad when the convolutions of the path hid it from her sight. Being new to the district, she had seen very little of Father Ruhl as yet, and somehow the penetrating knowledge and burning eyes of the pastor made her feel uncomfortable.

The soft drift, the lane of tall, motionless pines, stretched on in a quiet like death. Somewhere the sun, like a dead fire, had fallen into opalescent embers faintly luminous: they were enough only to touch the shadows with a ghastlier pallor. It was so still that the light crunch in the snow of the girl’s own footfalls trod on her heart like a desecration.

Suddenly there was something near her that had not been before. It had come like a shadow, without more sound or warning. It was here – there – behind her. She turned, in mortal panic, and saw a wolf. With a strangled cry and trembling limbs she strove to hurry on her way; and always she knew, though there was no whisper of pursuit, that the gliding shadow followed in her wake. Desperate in her terror, she stopped once more and faced it.

A wolf! – was it a wolf? O who could doubt it! Yet the wild expression in those famished eyes, so lost, so pitiful, so mingled of insatiable hunger and human need! Condemned, for its unspeakable sins, to take this form with sunset, and so howl and snuffle about the doors of men until the blessed day released it. A werewolf – not a wolf.

That terrific realisation of the truth smote the girl as with a knife out of darkness: for an instant she came near fainting. And then a low moan broke into her heart and flooded it with pity. So lost, so infinitely hopeless. And so pitiful – yes, in spite of all, so pitiful. It had sinned, beyond any sinning that her innocence knew or her experience could gauge; but she was a woman, very blest, very happy, in her store of comforts and her surety of love. She knew that it was forbidden to succour these damned and nameless outcasts, to help or sympathise with them in any way. But—

There was good store of meat in her basket, and who need ever know or tell? With shaking hands she found and threw a sop to the desolate brute – then, turning, sped upon her way.

But at home her secret sin stood up before her, and, interposing between her husband and herself, threw its shadow upon both their faces. What had she dared – what done? By her own act forfeited her birthright of innocence; by her own act placed herself in the power of the evil to which she had ministered. All that night she lay in shame and horror, and all the next day, until Stefan had come about his dinner and gone again, she moved in a dumb agony. Then, driven unendurably by the memory of his troubled, bewildered face, as twilight threatened she put on her cloak and went down to the little church in the hollow to confess her sin.

‘Mother, forgive, and save me,’ she whispered, as she passed the statue.

After ringing the bell for the confessor, she had not knelt long at the confessional box in the dim chapel, cold and empty as a waiting vault, when the chancel rail clicked, and the footsteps of Father Ruhl were heard rustling over the stones. He came, he took his seat behind the grating; and, with many sighs and falterings, Elspet avowed her guilt. And as, with bowed head, she ended, a strange sound answered her – it was like a little laugh, and yet not so much like a laugh as a snarl. With a shock as of death she raised her face. It was Father Ruhl who sat there – and yet it was not Father Ruhl. In that time of twilight his face was already changing, narrowing, becoming wolfish – the eyes rounded and the jaw slavered. She gasped, and shrunk back; and at that, barking and snapping at the grating, with a wicked look he dropped – and she heard him coming. Sheer horror lent her wings. With a scream she sprang to her feet and fled. Her cloak caught in something – there was a wrench and crash and, like a flood, oblivion overswept her.

It was the old deaf and near senile sacristan who found them lying there, the woman unhurt but insensible, the priest crushed out of life by the fall of the ancient statue, long tottering to its collapse. She recovered, for her part: for his, no one knows where he lies buried. But there were dark stories of a baying pack that night, and of an empty, bloodstained pavement when they came to seek for the body.

THE ACCURSED CORDONNIER

I

Poor Chrymelus, I remember, arose from the diversion of

a card-table, and dropped into the dwellings of darkness.

Hervey

It must be confessed that Amos Rose was considerably out of his element in the smoking-room off Portland Place. All the hour he remained there he was conscious of a vague rising nausea, due not in the least to the visible atmosphere – to which, indeed, he himself contributed languorously from a crackling spilliken of South American tobacco rolled in a maize leaf and strongly tinctured with opium – but to the almost brutal post-prandial facundity of its occupants.

Rose was patently a degenerate. Nature, in scheduling his characteristics, had pruned all superlatives. The rude armour of the flesh, under which the spiritual, like a hide-bound chrysalis, should develop secret and self-contained, was perished in his case, as it were, to a semi-opaque suit, through which his soul gazed dimly and fearfully on its monstrous arbitrary surroundings. Not the mantle of the poet, philosopher, or artist fallen upon such, can still its shiverings, or give the comfort that Nature denies.

Yet he was a little bit of each – poet, philosopher, and artist; a nerveless and self-deprecatory stalker of ideals, in the pursuit of which he would wear patent leather shoes and all the apologetic graces. The grandson of a ‘three-bottle’ JP, who had upheld the dignity of the State constitution while abusing his own in the best spirit of squirearchy; the son of a petulant dyspeptic, who alternated seizures of long moroseness with fits of abject moral helplessness, Amos found his inheritance in the reversion of a dissipated constitution, and an imagination as sensitive as an exposed nerve. Before he was thirty he was a neurasthenic so practised, as to have learned a sense of luxury in the very consciousness of his own suffering. It was a negative evolution from the instinct of self-protection – self-protection, as designed in this case, against the attacks of the unspeakable. Another evolution, only less negative, was of a certain desperate pugnacity, that derived from a sense of the inhuman injustice conveyed in the fact that temperamental debility not only debarred him from that bold and healthy expression of self that it was his nature to wish, but made him actually appear to act in contradiction to his own really sweet and sound predilections.

So he sat (in the present instance, listening and revolting) in a travesty of resignation between the stools of submission and defiance.

The neurotic youth of today renews no ante-existent type. You will look in vain for a face like Amos’s amongst the busts of the recovered past. The same weakness of outline you may point to – the sheep-like features falling to a blunt prow; the lax jaw and pinched temples – but not to that which expresses a consciousness that combative effort in a world of fruitless results is a lost desire.

Superficially, the figure in the smoking-room was that of a long, weedy young man – hairless as to his face; scalped with a fine lank fleece of neutral tint; pale-eyed, and slave to a bored and languid expression, over which he had little control, though it frequently misrepresented his mood. He was dressed scrupulously, though not obtrusively, in the mode, and was smoking a pungent cigarette with an air that seemed balanced between a genuine effort at self abstraction and a fear of giving offence by a too pronounced show of it. In this state, flying bubbles of conversation broke upon him as he sat a little apart and alone.

‘Johnny, here’s Callander preaching a divine egotism.’

‘Is he? Tell him to beg a lock of the Henbery’s hair. Ain’t she the dog that bit him?’

‘Once bit, twice shy.’

‘Rot! – In the case of a woman? I’m covered with their scars.’

‘What,’ thought Rose, ‘induced me to accept an invitation to this person’s house?’

‘A divine egotism, eh? It jumps with the dear Sarah’s humour. The beggar is an imitative beggar.’

‘Let the beggar speak for himself. He’s in earnest. Haven’t we been bred on the principle of self-sacrifice, till we’ve come to think a man’s self is his uncleanest possession?’

‘There’s no thinking about it. We’ve long been alarmed on your account, I can assure you.’

‘Oh! I’m no saint.’

‘Not you. Your ecstasies are all of the flesh.’

‘Don’t be gross. I—’

‘Oh! take a whisky and seltzer.’

‘If I could escape without exciting observation,’ thought Rose.

Lady Sarah Henbery was his hostess, and the inspired projector of a new scheme of existence (that was, in effect, the repudiation of any scheme) that had become quite the ‘thing’. She had found life an arbitrary design – a coil of days (like fancy pebbles, dull or sparkling) set in the form of a main spring, and each gem responsible to the design. Then she had said, ‘Today shall not follow yesterday or precede tomorrow’; and she had taken her pebbles from their setting and mixed them higgledy-piggledy, and so was in the way to wear or spend one or the other as caprice moved her. And she became without design and responsibility, and was thus able to indulge a natural bent towards capriciousness to the extent that – having a face for each and every form of social hypocrisy and licence – she was presently hardly to be put out of countenance by the extremest expression of either.

It followed that her reunions were popular with worldlings of a certain order.

By-and-by Amos saw his opportunity, and slipped out into a cold and foggy night.

II

De savoir votr’ grand age,

Nous serions curieux;

A voir votre visage,

Vous paraissez fort vieux;

Vous avez bien cent ans,

Vous montrez bien autant?

A stranger, tall, closely wrapped and buttoned to the chin, had issued from the house at the same moment, and now followed in Rose’s footsteps as he hurried away over the frozen pavement.

Suddenly this individual overtook and accosted him. ‘Pardon,’ he said. ‘This fog baffles. We have been fellow-guests, it seems. You are walking? May I be your companion? You look a little lost yourself.’

He spoke in a rather high, mellow voice – too frank for irony.

At another time Rose might have met such a request with some slightly agitated temporising. Now, fevered with disgust of his late company, the astringency of nerve that came to him at odd moments, in the exaltation of which he felt himself ordinarily manly and human, braced him to an attitude at once modest and collected.

‘I shall be quite happy,’ he said. ‘Only, don’t blame me if you find you are entertaining a fool unawares.’

‘You were out of your element, and are piqued. I saw you there, but wasn’t introduced.’

‘The loss is mine. I didn’t observe you – yes, I did!’

He shot the last words out hurriedly – as they came within the radiance of a street lamp – and his pace lessened a moment with a little bewildered jerk.

He had noticed this person, indeed – his presence and his manner. They had arrested his languid review of the frivolous forces about him. He had seen a figure, strange and lofty, pass from group to group; exchange with one a word or two, with another a grave smile; move on and listen; move on and speak; always statelily restless; never anything but an incongruous apparition in a company of which every individual was eager to assert and expound the doctrines of self.

This man had been of curious expression, too – so curious that Amos remembered to have marvelled at the little comment his presence seemed to excite. His face was absolutely hairless – as, to all evidence, was his head, upon which he wore a brown silk handkerchief loosely rolled and knotted. The features were presumably of a Jewish type – though their entire lack of accent in the form of beard or eyebrow made identification difficult – and were minutely covered, like delicate cracklin, with a network of flattened wrinkles. Ludicrous though the description, the lofty individuality of the man so surmounted all disadvantages of appearance as to overawe frivolous criticism. Partly, also, the full transparent olive of his complexion, and the pools of purple shadow in which his eyes seemed to swim like blots of resin, neutralised the superficial barrenness of his face. Forcibly, he impelled the conviction that here was one who ruled his own being arbitrarily through entire fearlessness of death.

‘You saw me?’ he said, noticing with a smile his companion’s involuntary hesitation. ‘Then let us consider the introduction made, without further words. We will even expand to the familiarity of old acquaintanceship, if you like to fall in with the momentary humour.’

‘I can see,’ said Rose, ‘that years are nothing to you.’

‘No more than this gold piece, which I fling into the night. They are made and lost and made again.’

‘You have knowledge and the gift of tongues.’

The young man spoke bewildered, but with a strange warm feeling of confidence flushing up through his habitual reserve. He had no thought why, nor did he choose his words or inquire of himself their source of inspiration.

‘I have these,’ said the stranger. ‘The first is my excuse for addressing you.’

‘You are going to ask me something.’

‘What attraction—’

‘Drew me to Lady Sarah’s house? I am young, rich, presumably a desirable parti. Also, I am neurotic, and without the nerve to resist.’

‘Yet you knew your taste would take alarm – as it did.’

‘I have an acute sense of delicacy. Naturally I am prejudiced in favour of virtue.’

‘Then – excuse me – why put yours to a demoralising test?’

‘I am not my own master. Any formless apprehension – any shadowy fear enslaves my will. I go to many places from the simple dread of being called upon to explain my reasons for refusing. For the same cause I may appear to acquiesce in indecencies my soul abhors; to give countenance to opinions innately distasteful to me. I am a quite colourless personality.’

‘Without force or object in life?’

‘Life, I think, I live for its isolated moments – the first half-dozen pulls at a cigarette, for instance, after a generous meal.’

‘You take the view, then—’

‘Pardon me. I take no views. I am not strong enough to take anything – not even myself – seriously.’

‘Yet you know that the trail of such volitionary ineptitude reaches backwards under and beyond the closed door you once issued from?’

‘Do I? I know at least that the ineptitude intensifies with every step of constitutional decadence. It may be that I am wearing down to the nerve of life. How shall I find that? diseased? Then it is no happiness to me to think it imperishable.’

‘Young man, do you believe in a creative divinity?’

‘Yes.’

‘And believe without resentment?’