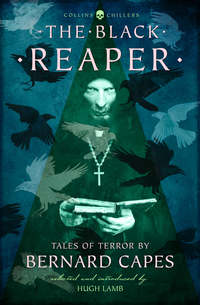

The Black Reaper: Tales of Terror by Bernard Capes

Thereafter conversation ensued; and it must be remarked that nothing was further from Rose’s mind than to apologise for his long intrusion and make a decent exit. Indeed, there seemed some thrill of vague expectation in the air, to the realisation of which his presence sought to contribute; and already – so rapidly grows the assurance of love – his heart claimed some protective right over the pure, beautiful creature at his feet.

For there, at a gesture from the other, had Adnah seated herself, leaning her elbow, quite innocently and simply, on the young man’s knee.

The sweet strong Moldavian wine buzzed in his head; love and sorrow and intense yearning went with flow and shock through his veins. At one moment elated by the thought that, whatever his understanding of the ethical sympathy existing between these two, their connection was, by their own acknowledgement, platonic; at another, cruelly conscious of the icy crevasse that must gape between so perfectly proportioned an organism and his own atrabilarious personality, he dreaded to avail himself of a situation that was at once an invitation and a trust; and ended by subsiding, with characteristic lameness, into mere conversational commonplace.

‘You must have got over a great deal of ground,’ said he to his host, ‘on that constitutional hobby horse of yours?’

‘A great deal of ground.’

‘In all weathers?’

‘In all weathers; at all times; in every country.’

‘How do you manage – pardon my inquisitiveness – the little necessities of dress and boots and such things?’

‘Adnah,’ said the stranger, ‘go fetch my walking suit and show it to our guest.’

The girl rose, went silently from the room, and returned in a moment with a single garment, which she laid in Rose’s hands.

He examined it curiously. It was a marvel of sartorial tact and ingenuity; so fashioned that it would have appeared scarcely a solecism on taste in any age. Built in one piece to resemble many, and of the most particularly chosen material, it was contrived and ventilated for any exigencies of weather and of climate, and could be doffed or assumed at the shortest notice. About it were cunningly distributed a number of strong pockets or purses for the reception of diverse articles, from a comb to a sandwich-box; and the position of these was so calculated as not to interfere with the symmetry of the whole.

‘It is indeed an excellent piece of work,’ said Amos, with considerable appreciation; for he held no contempt for the art which sometimes alone seemed to justify his right of existence.

‘Your praise is deserved,’ said the stranger, smiling, ‘seeing that it was contrived for me by one whose portrait, by Giambattista Moroni, now hangs in your National Gallery.’

‘I have heard of it, I think. Is the fellow still in business?’

‘The tailor or the artist? The first died bankrupt in prison – about the year 1560, it must have been. It was fortunate for me, inasmuch as I acquired the garment for nothing, the man disappearing before I had settled his claim.’

Rose’s jaw dropped. He looked at the beautiful face reclining against him. It expressed no doubt, no surprise, no least sense of the ludicrous.

‘Oh, my God!’ he muttered, and ploughed his forehead with his hands. Then he looked up again with a pallid grin.

‘I see,’ he said. ‘You play upon my fancied credulity. And how did the garment serve you in the central desert?’

‘I had it not then, by many centuries. No garment would avail against the wicked Samiel – the poisonous wind that is the breath of the eternal dead sand. Who faces that feels, pace by pace, his body wither and stiffen. His clothes crackle like paper, and so fall to fragments. From his eyeballs the moist vision flakes and flies in powder. His tongue shrinks into his throat, as though fire had writhed and consumed it to a little scarlet spur. His furrowed skin peels like the cerements of an ancient mummy. He falls, breaking in his fall – there is a puff of acrid dust, dissipated in a moment – and he is gone.’

‘And this you met unscathed?’

‘Yes; for it was preordained that Death should hunt, but never overtake me – that I might testify to the truth of the first Scriptures.’

Even as he spoke, Rose sprang to his feet with a gesture of uncontrollable repulsion; and in the same instant was aware of a horrible change that was taking place in the features of the man before him.

V

Trahentibus autem Judaeis Jesum extra praetorium cum venisset ad ostium, Cartaphilus praetorii ostiarius et Pontii Pilati, cum per ostium exiret Jesus, pepulit Eum pugno contemptibiliter post tergum, et irridens dixit, ‘Vade, Jesu citius, vade, quid moraris?’ Et Jesus severo vultu et oculo respiciens in eum, dixit: ‘Ego, vado, et expectabis donec veniam!’ Itaque juxta verbum Domini expectat adhuc Cartaphilus ille, qui tempore Dominicae passionis – erat quasi triginta annorum, et semper cum usque ad centum attigerit aetatem redeuntium annorum redit redivivus ad illum aetatis statum, quo fuit anno quand passus est Dominus.

Matthew of Paris, Historia Major

The girl – from whose cheek Rose, in his rough rising, had seemed to brush the bloom, so keenly had its colour deepened – sank from the stool upon her knees, her hands pressed to her bosom, her lungs working quickly under the pressure of some powerful excitement.

‘It comes, beloved!’ she said, in a voice half-terror, half-ecstasy.

‘It comes, Adnah,’ the stranger echoed, struggling – ‘this periodic self-renewal – this sloughing of the veil of flesh that I warned you of.’

His soul seemed to pant grey from his lips; his face was bloodless and like stone; the devils in his eyes were awake and busy as maggots in a wound. Amos knew him now for wickedness personified and immortal, and fell upon his knees beside the girl and seized one of her hands in both his.

‘Look!’ he shrieked. ‘Can you believe in him longer? believe that any code or system of his can profit you in the end?’

She made no resistance, but her eyes still dwelt on the contorted face with an expression of divine pity.

‘Oh, thou sufferest!’ she breathed; ‘but thy reward is near!’

‘Adnah!’ wailed the young man, in a heartbroken voice. ‘Turn from him to me! Take refuge in my love. Oh, it is natural, I swear. It asks nothing of you but to accept the gift – to renew yourself in it, if you will; to deny it, if you will, and chain it for your slave. Only to save you and die for you, Adnah!’

He felt the hand in his shudder slightly; but no least knowledge of him did she otherwise evince.

He clasped her convulsively, released her, mumbled her slack white fingers with his lips. He might have addressed the dead.

In the midst, the figure before them swayed with a rising throe – turned – staggered across to the couch, and cast itself down before the crucifix on the wall.

‘Jesu, Son of God,’ it implored, through a hurry of piercing groans, ‘forbear Thy hand: Christ, register my atonement! My punishment – eternal – and oh, my mortal feet already weary to death! Jesu, spare me! Thy justice, Lawgiver – let it not be vindictive, oh, in Thy sacred name! lest men proclaim it for a baser thing than theirs. For a fault of ignorance – for a word of scorn where all reviled, would they have singled one out, have made him, most wretched, the scapegoat of the ages? Ah, most holy, forgive me! In mine agony I know not what I say. A moment ago I could have pronounced it something seeming less than divine that Thou couldst so have stultified with a curse Thy supreme hour of self-sacrifice – a moment ago, when the rising madness prevailed. Now, sane once more – Nazarene, oh, Nazarene! not only retribution for my deserts, but pity for my suffering – Nazarene, that Thy slanderers, the men of little schisms, be refuted, hearing me, the very witness to Thy mercy, testify how the justice of the Lord triumphs supreme through that His superhuman prerogative – that they may not say, He can destroy, even as we; but can He redeem? The sacrifice – the yearling lamb; – it awaits Thee, Master, the proof of my abjectness and my sincerity. I, more curst than Abraham, lift my eyes to Heaven, the terror in my heart, the knife in my hand. Jesu – Jesu!’

He cried and grovelled. His words were frenzied, his abasement fulsome to look upon. Yet it was impressed upon one of the listeners, with a great horror, how unspeakable blasphemy breathed between the lines of the prayer – the blasphemy of secret disbelief in the Power it invoked, and sought, with its tongue in its cheek, to conciliate.

Bitter indignation in the face of nameless outrage transfigured Rose at this moment into something nobler than himself. He feared, but he upheld his manhood. Conscious that the monstrous situation was none of his choosing, he had no thought to evade its consequences so long as the unquestioning credulity of his co-witness seemed to call for his protection. Nerveless, sensitive natures, such as his, not infrequently give the lie to themselves by accesses of an altruism that is little less than self-effacement.

‘This is all bad,’ he struggled to articulate. ‘You are hipped by some devilish cantrip. Oh, come – come! – in Christ’s name I dare to implore you – and learn the truth of love!’

As he spoke, he saw that the apparition was on its feet again – that it had returned, and was standing, its face ghastly and inhuman, with one hand leaned upon the marble table.

‘Adnah!’ it cried, in a strained and hollow voice. ‘The moment for which I prepared you approaches. Even now I labour. I had thought to take up the thread on the further side; but it is ordained otherwise, and we must part.’

‘Part!’ The word burst from her in a sigh of lost amazement.

‘The holocaust, Adnah!’ he groaned – ‘the holocaust with which every seventieth year my expiation must be punctuated! This time the cross is on thy breast, beloved; and tomorrow – oh! thou must be content to tread on lowlier altitudes than those I have striven to guide thee by.’

‘I cannot – I cannot, I should die in the mists. Oh, heart of my heart, forsake me not!’

‘Adnah – my selma, my beautiful – to propitiate—’

‘Whom? Thou hast eaten of the Tree, and art a God!’

‘Hush!’ He glanced round with an awed visage at the dim hanging Calvary; then went on in a harsher tone, ‘It is enough – it must be.’ (His shifting face, addressed to Rose, was convulsed into an expression of bitter scorn). ‘I command thee, go with him. The sacrifice – oh, my heart, the sacrifice! And I cry to Jehovah, and He makes no sign; and into thy sweet breast the knife must enter.’

Amos sprang to his feet with a loud cry.

‘I take no gift from you. I will win or lose her by right of manhood!’

The girl’s face was white with despair.

‘I do not understand,’ she cried in a piteous voice.

‘Nor I,’ said the young man, and he took a threatening step forward. ‘We have no part in this – this lady and I. Man or devil you may be; but—’

‘Neither!’

The stranger, as he uttered the word, drew himself erect with a tortured smile. The action seemed to kilt the skin of his face into hideous plaits.

‘I am Cartaphilus,’ he said, ‘who denied the Nazarene shelter.’

‘The Wandering Jew!’

The name of the old strange legend broke involuntarily from Rose’s lips.

‘Now you know him!’ he shrieked then. ‘Adnah, I am here! Come to me!’

Tears were running down the girl’s cheeks. She lifted her hands with an impassioned gesture; then covered her face with them.

But Cartaphilus, penetrating the veil with eyes no longer human, cried suddenly, so that the room vibrated with his voice, ‘Bismillah! Wilt thou dare the Son of Heaven, questioning if His sentence upon the Jew – to renew, with his every hundredth year, his manhood’s prime – was not rather a forestalling through His infinite penetration, of the consequences of that Jew’s finding and eating of the Tree of Life? Is it Cartaphilus first, or Christ?’

The girl flung herself forward, crushing her bosom upon the marble floor, and lay blindly groping with her hands.

‘He was a God and vindictive!’ she moaned. ‘He was a man and He died. The cross – the cross!’

The lost cry pierced Rose’s breast like a knife. Sorrow, rage, and love inflamed his passion to madness. With one bound he met and grappled with the stranger.

He had no thought of the resistance he should encounter. In a moment the Jew, despite his age and seizure, had him broken and powerless. The fury of blood blazed down upon him from the unearthly eyes.

‘Beast! that I might tear you! But the Nameless is your refuge. You must be chained – you must be chained. Come!’

Half-dragging, half-bearing, he forced his captive across the room to the corner where the flask of topaz liquid stood.

‘Sleep!’ he shrieked, and caught up the glass vessel and dashed it down upon Rose’s mouth.

The blow was a stunning one. A jagged splinter tore the victim’s lip and brought a gush of blood; the yellow fluid drowned his eyes and suffocated his throat. Struggling to hold his faculties, a startled shock passed through him, and he dropped insensible on the floor.

VI

‘Wandering stars, to whom is reserved the blackness of darkness for ever.’

Where had he read these words before? Now he saw them as scrolled in lightning upon a dead sheet of night.

There was a sound of feet going on and on.

Light soaked into the gloom, faster – faster; and he saw—

The figure of a man moved endlessly forward by town and pasture and the waste places of the world. But though he, the dreamer, longed to outstrip and stay the figure and look searchingly in its face, he could not, following, close upon the intervening space; and its back was ever towards him.

And always as the figure passed by populous places, there rose long murmurs of blasphemy to either side, and bestial cries: ‘We are weary! the farce is played out! He reveals Himself not, nor ever will! Lead us – lead us, against Heaven, against hell; against any other, or against ourselves! The cancer of life spreads, and we cannot enjoy nor can we think cleanly. The sins of the fathers have accumulated to one vast mound of putrefaction. Lead us, and we follow!’

And, uttering these cries, swarms of hideous half-human shapes would emerge from holes and corners and rotting burrows, and stumble a little way with the figure, cursing and jangling, and so drop behind, one by one, like glutted flies shaken from a horse.

And the dreamer saw in him, who went ever on before, the sole existent type of a lost racial glory, a marvellous survival, a prince over monstrosities; and he knew him to have reached, through long ages of evil introspection, a terrible belief in his own self-acquired immortality and lordship over all abased peoples that must die and pass; and the seed of his blasphemy he sowed broadcast in triumph as he went; and the ravenous horrors of the earth ran forth in broods and devoured it like birds, and trod one another underfoot in their gluttony.

And he came to a vast desolate plain, and took his stand upon a barren drift of sand; and the face the dreamer longed and feared to see was yet turned from him.

And the figure cried in a voice that grated down the winds of space: ‘Lo! I am he that cannot die! Lo! I am he that has eaten of the Tree of Life; who am the Lord of Time and of the races of the earth that shall flock to my standard!’

And again: ‘Lo! I am he that God was impotent to destroy because I had eaten of the fruit! He cannot control that which He hath created. He hath builded His temple upon His impotence, and it shall fall and crush Him. The children of His misrule cry out against Him. There is no God but Antichrist!’

Then from all sides came hurrying across the plain vast multitudes of the degenerate children of men, naked and unsightly; and they leaped and mouthed about the figure on the hillock, like hounds baying a dead fox held aloft; and from their swollen throats came one cry:

‘There is no God but Antichrist!’

And thereat the figure turned about – and it was Cartaphilus the Jew.

VII

There is no death! What seems so is transition.

Uttering an incoherent cry, Rose came to himself with a shock of agony and staggered to his feet. In the act he traversed no neutral ground of insentient purposelessness. He caught the thread of being where he had dropped it – grasped it with an awful and sublime resolve that admitted no least thought of self-interest.

If his senses were for the moment amazed at their surroundings – the silence, the perfumed languor, the beauty and voluptuousness of the room – his soul, notwithstanding, stood intent, unfaltering – waiting merely the physical capacity for action.

The fragments of the broken vessel were scattered at his feet; the blood of his wound had hardened upon his face. He took a dizzy step forward, and another. The girl lay as he had seen her cast herself down – breathing, he could see; her hair in disorder; her hands clenched together in terror or misery beyond words.

Where was the other?

Suddenly his vision cleared. He saw that the silken curtains of the alcove were closed.

A poniard in a jewelled sheath lay, with other costly trifles, on a settle hard by. He seized and, drawing it, cast the scabbard clattering on the floor. His hands would have done; but this would work quicker.

Exhaling a quick sigh of satisfaction, he went forward with a noiseless rush and tore apart the curtains.

Yes – he was there – the Jew – the breathing enormity, stretched silent and motionless. The shadow of the young man’s lifted arm ran across his white shirt front like a bar sinister.

To rid the world of something monstrous and abnormal – that was all Rose’s purpose and desire. He leaned over to strike. The face, stiff and waxen as a corpse’s, looked up into his with a calm impenetrable smile – looked up, for all its eyes were closed. And this was a horrible thing, that, though the features remained fixed in that one inexorable expression, something beneath them seemed alive and moving – something that clouded or revealed them as when a sheet of paper glowing in the fire wavers between ashes and flame. Almost he could have thought that the soul, detached from its envelope, struggled to burst its way to the light.

An instant he dashed his left palm across his eyes; then shrieking, ‘Let the fruit avail you now!’ drove the steel deep into its neck with a snarl.

In the act, for all his frenzy, he had a horror of the spurting blood that he knew must foul his hand obscenely, and sprinkle his face, perhaps, as when a finger half-plugs a flowing water-tap.

None came! The fearful white wound seemed to suck at the steel, making a puckered mouth of derision.

A thin sound, like the whinny of a dog, issued from Rose’s lips. He pulled out the blade – it came with a crackling noise, as if it had been drawn through parchment.

Incredulous – mad – in an ecstasy of horror, he stabbed again and again. He might as fruitfully have struck at water. The slashed and gaping wounds closed up so soon as he withdrew the steel, leaving not a scar.

With a scream he dashed the unstained weapon on the floor and sprang back into the room. He stumbled and almost fell over the prostrate figure of the girl.

A strength as of delirium stung and prickled in his arms. He stooped and forcibly raised her – held her against his breast – addressed her in a hurried passion of entreaty.

‘In the name of God, come with me! In the name of God, divorce yourself from this horror! He is the abnormal! – the deathless – the Antichrist!’

Her lids were closed; but she listened.

‘Adnah, you have given me myself. My reason cannot endure the gift alone. Have mercy and be pitiful, and share the burden!’

At last she turned on him her swimming gaze.

‘Oh! I am numbed and lost! What would you do with me?’

With a sob of triumph he wrapped his arms hard about her, and sought her lips with his. In the very moment of their meeting, she drew herself away, and stood panting and gazing with wide eyes over his shoulder. He turned.

A young man of elegant appearance was standing by the table where he had lately leaned.

In the face of the newcomer the animal and the fanatic were mingled, characteristics inseparable in pseudo-revelation.

He was unmistakably a Jew, of the finest primitive type – such as might have existed in preneurotic days. His complexion was of a smooth golden russet; his nose and lips were cut rather in the lines of sensuous cynicism; the look in his polished brown eyes was of defiant self-confidence, capable of the extremes of devotion or of obstinacy. Short curling black hair covered his scalp, and his moustache and small crisp beard were of the same hue.

‘Thanks, stranger,’ he said, in a somewhat nasal but musical voice. ‘Your attack – a little cowardly, perhaps, for all its provocation – has served to release me before my time. Thanks – thanks indeed!’

Amos sent a sick and groping glance towards the alcove. The curtain was pulled back – the couch was empty. His vision returning, caught sight of Adnah still standing motionless.

‘No, no!’ he screeched in a suffocated voice, and clasped his hands convulsively.

There was an adoring expression in her wet eyes that grew and grew. In another moment she had thrown herself at the stranger’s feet.

‘Master,’ she cried, in a rich and swooning voice: ‘O Lord and Master – as blind love foreshadowed thee in these long months!’

He smiled down upon her.

‘A tender welcome on the threshold,’ he said softly, ‘that I had almost renounced. The young spirit is weak to confirm the self-sacrifice of the old. But this ardent modern, Adnah, who, it seems, has slipped his opportunity?’

Passionately clasping the hands of the young Jew, she turned her face reluctant.

‘He has blood on him,’ she whispered. ‘His lip is swollen like a schoolboy’s with fighting. He is not a man, sane, self-reliant and glorious – like you, O my heart!’

The Jew gave a high, loud laugh, which he checked in mid-career.

‘Sir,’ he said derisively, ‘we will wish you a very pleasant good-morning.’

How – under what pressure or by what process of self-effacement – he reached the street, Amos could never remember. His first sense of reality was in the stinging cold, which made him feel, by reaction, preposterously human.

It was perhaps six o’clock of a February morning, and the fog had thinned considerably, giving place to a wan and livid glow that was but half-measure of dawn.

He found himself going down the ringing pavement that was talcous with a sooty skin of ice, a single engrossing resolve hammering time in his brain to his footsteps.

The artificial glamour was all past and gone – beaten and frozen out of him. The rest was to do – his plain duty as a Christian, as a citizen – above all, as a gentleman. He was, unhypnotised, a law-abiding young man, with a hatred of notoriety and a detestation of the abnormal. Unquestionably his forebears had made a huge muddle of his inheritance.

About a quarter to seven he walked (rather unsteadily) into Vine Street Police Station and accosted the inspector on duty.

‘I want to lay an information.’

The officer scrutinised him, professionally, from the under side, and took up a pen.

‘What’s the charge?’

‘Administering a narcotic, attempted murder, abduction, profanity, trading under false pretences, wandering at large – great heavens! what isn’t it?’

‘Perhaps you’ll say. Name of accused?’

‘Cartaphilus.’

‘Any other?’

‘The Wandering Jew.’

The Inspector laid down his pen and leaned forward, bridging his finger-tips under his chin.

‘If you take my advice,’ he said, ‘you’ll go and have a Turkish bath.’

The young man grasped and frowned.

‘You won’t take my information?’

‘Not in that form. Come again by-and-by.’