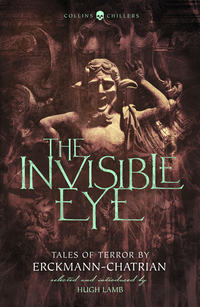

The Invisible Eye: Tales of Terror by Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian

She did not have the time to finish. A silence of death followed her words. I looked around. The phantasmagoria had disappeared.

Then the sound of a horn struck my ears. Outside, horses were prancing, dogs barking, and the moon, calm, contemplative, shone into my alcove. The door opened, as by a wind, and fifty hunters, followed by young ladies, two hundred years old, with long trailing gowns, filed majestically from one hall to the other. Four serfs also passed, bearing on their stout shoulders a stretcher of oak branches on which rested – bleeding, frothy at the mouth, with glazed eyes – an enormous wild boar. I heard the sound of the horn still louder outside. Then it died away in the woodlands like the sleepy cry of a bird … and then … nothing!

As I was thinking of this strange vision, I looked by chance in the silent shadows, and was astonished to see the hall occupied by one of those old Protestant families of bygone days, calm, dignified, and solemn in their manners. There was the white-haired father, reading a big Bible; the old mother, tall and pale, spinning the household linen, straight as a spindle, with a collar up to her ears, her waist bound by fillets of black ratteen; then the chubby children with dreaming eyes leaning on the table in deep silence; the old sheep dog, listening to his master; the old clock in its walnut case, counting the seconds; and farther away, in the shadow, the faces of girls and the features of lads in drugget jackets and felt hats, discussing the story of Jacob and Rachel by way of declaring their love.

And this worthy family seemed to be convinced of the holy truths; the old father, with his cracked voice, continued the edifying story with deep emotion:

‘This is your promised land … the land of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob … which I have designed for you from the beginning of the world … so that you shall grow and multiply there like the stars of the sky. And none shall take it from you … for you are my beloved people, in whom I have put my trust.’

The moon, clouded for a few moments, grew clear again, and hearing nothing more I turned my head. The calm cold rays lighted up the empty hall; not a figure, not a shadow … The light streamed on the floor, and, in the distance, some trees lifted their foliage, sharp and clear, against the luminous hillside.

But suddenly the high walls were hidden in books. The old spinet gave way to the desk of a learned man, whose big wig showed to me above an armchair of red leather. I heard the goose-quill scratching the paper. The writer, lost in thought, did not stir. The silence overwhelmed me. But great was my surprise when the man turned in his chair, and I recognised in him the original of the portrait of the Jurist Gregorius that is No. 253 in the Hesse-Darmstadt Picture Gallery. Heavens! how did this great person descend from his frame? That is what I was asking myself when in a hollow voice he cried, ‘Ownership, in civil law, is the right to use and abuse so far as the law of nature allows.’ As this formula came from his lips, his figure grew dimmer and dimmer. At the last word he could not be seen.

What more shall I tell you, my dear friends? During the following hours I saw twenty other generations succeed each other in the ancient castle of Hans Burckart … Christians and Jews, lords and commoners, ignorant people and learned, artists and philistines, and all of them claimed the place as their legitimate property. All thought themselves the sovereign masters of the property. Alas! the wind of death blew them out of the door. I ended by becoming accustomed to this strange procession. Each time one of these worthy persons cried, ‘This is mine!’ I laughed and murmured, ‘Wait, my friend, wait, you will vanish like the rest.’

I was weary when, far away, very far away, a cock crowed, and with his piercing voice awoke the sleeping world. The leaves shook in the morning wind, and a shudder ran through my body. I felt my limbs were at last free, and rising on my elbow I gazed with rapture over the silent countryside … But what I saw was scarcely calculated to make me rejoice. All along the little hill-path that led to the graveyard climbed the procession of phantoms that had visited me in the night. Step by step they advanced to the lich-gate, and in their silent march, under the vague grey shadowy tints of the rising dawn, there was something terrible. As I looked, more dead than alive, my mouth gaping, my forehead bathed in a cold sweat, the leaders of the procession seemed to melt into the old weeping willows. There remained only a little number of spectres. And I was beginning to recover my breath, when my uncle Christian, the last figure in the procession, turned round under the old gate, and motioned to me to come with him. A voice, far away … ironical, cried: ‘Kasper … Kasper … Come … This land is ours!’

Then everything disappeared, and a purple line, stretching across the horizon, announced the dawn. I need not tell you that I did not accept the invitation of Master Christian Haas. It will be necessary for someone more powerful than he to force me to take that road. But I must admit that my night in the castle of Burckart has singularly altered the good opinion I had conceived of my own importance. For the strange vision seemed to me to signify that if the land, the orchards, the meadows do not pass away, the owners vanish very quickly. It makes the hair rise on your head when you think on it seriously.

So, far from letting myself slumber in the delight of an idle country life, I took up music again, and I hope next year to have an opera produced in Berlin. The fact is that glory, which common-sense people regard as moonshine, is still the most solid of all forms of ownership. It does not end with life. On the contrary, death confirms it, and gives it a new lustre. Suppose, for example, that Homer returned to this world. No one would think of denying him the merit of having written the Iliad, and each of us would hasten to render to this great man the honours due to him. But if by chance the richest landowner of his age returned to claim the fields, the forests, the pasturages, which were the pride of his life, it is ten to one he would be treated as a thief, and perish miserably under the blows of the Turks.

THE WILD HUNTSMAN

I

In those happy days of youth, when the sky appears of a deeper blue and the foliage of a more vivid green, when mountain-torrents rush down with greater impetuosity and noise, when lakes are calmer, and their limpid depths more clear; when Nature is clothed in unspeakable grace, and all things sing to us in our hearts, and whisper of love, of art, of poetry – in that happy time I wandered alone through the grand old forest of Hundsrück.

I wandered from town to town, from one forester’s house to the next; singing, whistling, looking about me, without any definite object; fancy-led, seeking ever a deeper depth still more distant and more leafy, where no sound but the whisperings of the wind and the music of trees could ever reach me.

One morning I stepped out before daylight from the door of the Swan hostelry at Pirmasens to cross the wooded hills of Rothalps to the hamlet of Wolfthal. The boots came to arouse me at two o’clock, as I had requested; for towards the end of August it is best to travel at night, as the heat during the day, concentrating at the bottom of the gorges, becomes insupportable.

Picture me, then, on the way at night, my hunting-jacket buttoned closely to my figure, my knapsack depending from my shoulders, my stick in my hand. I walked at a good pace. Vines succeeded to vines, hemp-fields to hemp-fields; then came fir-trees, amongst which the darkened pathway wended; and the pale moon overhead seemed to plough an immense furrow of light beyond.

The excitement of the walk, the deep silence of the solitude, the twittering of a bird disturbed in its nest, the rapid passage through the trees of an early squirrel going to drink at a neighbouring spring, the stars glinting between the hills, the distant murmur of the water in the valley, the first clear notes from the thrush uttered from the topmost spray of the pine-tree, and crying to us that far, far away there was a streak of light, that the day was breaking, and at length the pale crepuscule, the first purple tint on the horizon, appeared across the dark coppices – these numerous impressions of the journey insensibly led up to the birth of the day.

About five o’clock I came out upon the other side of the Rothalps, nine miles from Pirmasens, into a narrow winding gorge.

I can always recall the sensation of freshness and delight with which I welcomed this retreat. Below me a little torrent, clear as crystal, rushed over its moss-grown stones; on the right, as far as the eye could reach, extended a forest of birch; and to the left, beneath the lofty pine-trees’ shade, the sandy path meandered to the deep roads.

Below the road the heather and the heaths sprang up with golden drops; still farther away some briars, and then a streak of water with its clustering green cresses.

Those who during their youth have had the happiness to light upon such a place in the forest depths, at that hour when Nature comes forth from her rosy bath and in her robe of sunshine, when the light plays amongst the foliage, and drops its golden tears into the untrodden depths, when the mosses, the honeysuckle, and all climbing plants burn incense in the shade, and mingle their perfumes under the canopy of the lofty palm-trees, when the parti-coloured tomtits hop from branch to branch in search of insects, when the thrush, the bullfinch, and the blackbird fly down to the rivulet and drink their fill, with wings outstretched over the tiny foaming falls, or the thieving jays, crossing above the trees in flocks, direct their flight towards the wild cherry-trees – at the hour, in short, when all Nature is animated, when everything is enjoying love, and light, and life – such people as those to whom I have referred alone can understand my ecstasy.

I seated myself upon the root of an ancient moss-grown oak, my stick resting idly between my knees; and there, for the space of an hour, I abandoned myself, child-like, to endless day-dreams.

By degrees the light increased; the humming of insects grew louder, while the melancholy notes of the cuckoos, repeated by the echoes, marked in a curious way the measure of the universal concert.

While I was thus meditating, a distant sharp note, skilfully modulated, struck upon my ear. From the moment of my arrival at this spot I had heard, without paying any attention to, this note; but so soon as I had distinguished it from the numerous forest noises I thought: ‘That is the note of a bird-catcher, his hut cannot be far away, and there must be some forester’s house close by.’

I arose and looked about me. Towards the left hand, in the direction of the rising ground, I quickly distinguished a penthouse roof whose dormer windows and white chimneys glistened amid the innumerable branches of the forest pines. The house was quite half an hour’s walk from my resting-place, but that did not prevent me saying aloud, ‘Thank Heaven!’

For it is no small matter, I may tell you, to know where to find a crust of bread and a flask of kirchenwasser. So I once again shouldered my knapsack, and cheerfully struck into the path which promised to lead me to the house.

For some few minutes longer the bird-catcher’s call continued its cheery notes; then, all of a sudden, it ceased. Towards seven o’clock the small birds would have finished their morning ‘grub’, and the day, waxing hotter and brighter, would discover the lurking enemy behind the thick leafy screen of his hiding-place; it was time to take up the birdlime.

All these thoughts passed through my mind as I continued to advance, regretting that I had not sooner resumed my journey, when about fifty or sixty paces to the left I caught sight of the bird-catcher, a fine old forester, tall, sinewy, and muscular, clad in a short blue blouse, an immense game-bag depending from his shoulder, the silver badge upon his chest, and the small peaked cap placed jauntily upon his head. He was in the act of taking up his nets, and at first I only caught sight of his broad back, his long muscular limbs arrayed in cloth gaiters reaching up above the knee beneath his blouse; but as he turned I perceived the wiry profile of a regular old huntsman, the grey eyes shaded by long lashes; a long white moustache shrouded the lips; snowy eyebrows, an honest profile, somewhat stem, yet with something of a thoughtful, even a rather ingenuous cast; but the silver-grey hair, and a certain indescribable look in the depths of the eyes, corrected the easy-going impression which struck one at first sight. And if the broad back was somewhat bent, the thin shoulders were so wide that one could not help feeling a certain respect for this fine old forester.

He moved about in all directions, sometimes in the light, sometimes in the shadow, stretching out a hand here, stooping there, perfectly at home. Resting upon my stick, I watched him narrowly, and thought what a capital subject for a picture he would make.

Having taken up his nets and twigs, and wrapped them carefully, he proceeded to string together by the beaks the birds he had captured, the smallest first, garland fashion. At length, having arranged them to his liking, he plunged them all into his game-bag; then swinging it upon his shoulders, he took up the great holly staff that was lying upon the ground beside him, and struck out towards the path.

Then for the first time he noticed me, and his face assumed an official expression consistent with his dress, but involuntarily his sternness disappeared, and his grey eyes beamed kindly upon me.

‘Ha, ha!’ he exclaimed in French, but with a curious German accentuation, ‘good morning, monsieur; how are you this morning? Is it to your taste?’

‘Yes, pretty well,’ I replied in the same language.

‘Ha, ha!’ said the brave fellow, ‘you are a Frenchman, then; I saw that at once!’ and he saluted like an old soldier. ‘Are you not a Frenchman?’ he added.

‘Well, not exactly, I come from Dusseldorf.’

‘Ah! from Dusseldorf; but it is all the same,’ he said, as he lapsed into the old German tongue; ‘you are a good fellow nevertheless.’

He placed his hand lightly upon my shoulder as he spoke.

‘You are en route early,’ he said.

‘Yes, I come from Pirmasens.’

‘It is nine good miles from here; you must have set out at three o’clock this morning.’

‘At two o’clock, but I halted for an hour in the dell yonder.’

‘Ah! yes, near the source of the Vellerst. And, if not impertinent, may I inquire your destination?’

‘My destination! Oh! I go anywhere. I walk about, look around me—’

‘You are a timber contractor, then?’

‘No, I am a painter.’

‘A painter – good. A capital profession that. Why you can make three or four crowns a day, and walk about with your hands in your pockets meanwhile. Painters have been here before. I have seen two or three in the last thirty years. It is a capital calling.’

We pursued our way towards the house together, he with bent back, stretching out his long limbs, while I came trudging after, congratulating myself on having pitched upon a resting-place. The sun was getting very warm, and the ascent was steep. At intervals long vistas opened out to the left, and mingled together in deep gorges; the blue distance trended down towards the Rhine, and beyond the hazy horizon mingled with the sky and passed into the infinite.

‘What a splendid country!’ I cried as I stood wrapped in contemplation of this wonderful panorama.

The old keeper stopped as I spoke; his piercing eyes took in the prospect, and he replied gravely: ‘That’s true! I have the most beautiful district of all the mountain as far as Neustadt. Every one who comes to see the country says so; even the ranger himself confesses as much. Now look yonder. Do you see the Losser descending between those rocks? Look at that white line – that is the foam. You must see that closer, sir. You should hear the roar of the cataract in the spring when the snows are melting; it is like thunder amongst the hills. Then look higher up; do you see the blossom of the heather and the broom? Well, there is the Valdhorn; the flowers are falling just now, but in the spring you would perceive a bouquet that rises to heaven. And if you are fond of curiosities, there is the Birckenstein; we must not forget that. All the learned people – for one or two such do come here during the year – never fail to go and read the old inscriptions upon the stones.’

‘It is a ruin, then?’

‘Yes; an old piece of wall upon a rock enveloped in nettles and brambles – a regular owl’s nest. For my own part, I like the Losser, the Krapenfelz, the Valdhorn; but as they say in France, every one has his own taste and colour. We have everything here, high, medium-sized, and young forest trees, brushwood and brambles, rocks, caverns, torrents, rivers—’

‘But no lakes,’ I said.

‘Lakes!’ he exclaimed. ‘No lakes! As if we had not just beyond the Losser a lake a league in circumference, dark and deep, surrounded by rocks and the giant pines of the Veierschloss! They call it The Lake of the Wild Huntsman!’

And he bent his head as if in reflection for some seconds. Then suddenly rousing himself, he resumed his route without uttering a word. It appeared to me that the old keeper so lately enraptured had suddenly struck upon a melancholy chord. I followed him musing. He, bending forward, wearing a pensive air, and learning on his great holly staff, took such long and vigorous strides that it seemed as if his limbs would burst through his blouse every moment!

The forester’s house came into sight between the trees in the midst of a verdant meadow. At the end of the valley the river could be perceived following the undulations of the hills; farther still in the gorge were clusters of fruit-trees, some tilled ground, a small garden surrounded by a low wall, and finally on a terrace having the wood for a background was the house of the old keeper – a white house, somewhat ancient in appearance, with three windows, and the door on the ground floor, four windows above with little diamond-shaped panes, and four others in the garrets amid the brown tiles of the roof.

Facing the wood in our direction was an old worm-eaten gallery with a carved balustrade, the winding staircase outside being fastened to the wall. A lattice trellis-work occupied two sides upon which the honeysuckles and vines clambered and hung back in festoons from the roof. Across the green sward the small black window-panes glittered in the shade. On the wall of the kitchen garden an old chanticleer was proudly strutting in the midst of his hens; upon the mossy roof a flock of pigeons were moving about; in the stream a number of ducks were swimming, and from the threshold we could have perceived the length of the sloping dell, the extensive valley, and the leafy forest shades as far as the eye could reach.

Nothing so calm and peaceable as this house, lost in the solitudes of the mountains, can be imagined; its very appearance touched one more than you might fancy, and made one feel inclined to live and die there – if possible.

Two old hounds ran out to welcome us. A young girl was hanging some linen out to dry upon the balustrade, and seeing the dogs running out, looked up. The old keeper smiled as he pressed forward.

‘You are at home here,’ I said.

‘Yes, this is my house.’

‘May I ask for a crust and a glass of wine?’

‘Of course, man, of course. If the keepers sent people away I wonder to what inn the travellers could go. You are right welcome, sir.’

At this moment we reached the gate in the palings of the little garden; the dogs jumped upon us, and the girl in the balcony waved her hand in welcome. At the end of the garden another gate gave us admission to the yard, and the keeper, turning to me, exclaimed in a joyous tone: ‘You are now at the house of Frantz Honeck, gamekeeper to the Grand Duke Ludwig. Come into the parlour. I will just get rid of my game-bag, take off my gaiters, and join you there.’

We traversed a narrow passage. Talking as we advanced, the keeper pushed open the door of a low square whitewashed room, furnished with beechwood chairs, having a heart-shaped ornament cut in the back of each, a high walnut-wood press, with glittering hinges and rounded feet, and at the farther end was an old Nuremberg clock. In the corner to the right stood the stove, and by the lattice-windows was a firwood table; these made up the furniture of the room. On the table were a small loaf of bread and two glasses.

‘Sit down. Make yourself comfortable,’ said the old keeper. ‘I will return in a few moments.’

He left the room as he spoke.

I heard him enter the next room. Then, delighted to find myself in such good quarters, I took off my great-coat. The dogs stretched themselves on the floor.

‘Louise! Louise!’ cried out old Frantz.

The young girl passed the windows, and her pretty rosy face put aside the plants to look into the room. I bowed to her. She blushed, and hastily retired.

‘Louise!’ cried the old man again.

‘I am here, grandfather, I am here,’ she replied gently as she came into the passage.

Then I could not help hearing their conversation.

‘There is a traveller come, a fine lad; he will breakfast here. Go and draw a flask of white wine, and put on two plates.’

‘Yes, grandfather.’

‘Go and fetch my woollen jacket and my sabots. The birds have turned out well this morning; the young man comes from the Swan at Pirmasens. When Caspar returns send him in.’

‘He is tending the cows, grandfather, shall I call him?’

‘No, an hour hence will do.’

Every word reached me distinctly. Outside dogs barked, hens cackled, the leaves rustled gently in the breeze; everything was cheerful, fresh, and green.

I placed my knapsack upon the table and sat down thinking of the happiness of living in such a place without any care beyond the daily work.

‘What a life!’ I thought. ‘One can breathe freely here. This old Frantz is as tough as an oak notwithstanding his seventy years. And what a charming little girl his granddaughter is!’

I had scarcely finished these reflections when the old man, clad in his knitted vest and his iron-tipped sabots, came in laughing, and cried out: ‘Here I am. I have finished my morning’s work. I was up and about before you, sir; at four o’clock I had gone my round of the felled timber. Now we are going to rest ourselves, you and I; take a quiet glass and smoke another pipe – pipes again! But tell me, do you wish to change? You can go up to my room.’

‘Thank you, Père Frantz, I have need of nothing but a little rest.’

This title of Père Frantz appeared to please the old man; his cheeks betrayed a smile.

‘’Tis true that my name is Frantz,’ he said, ‘and I am old enough to be your father – ay, your grandfather. But may I ask your age?’

‘I am nearly twenty-two.’

At this moment the little Louise entered, carrying a flask of white wine in one hand, and in the other some cheese, upon a beautiful specimen of Delft ware, ornamented with red flowers. Frantz ceased to speak as she came in, thinking, perhaps, it is better to hold his tongue about age in the presence of his granddaughter.

Louise was about sixteen years of age; she was fair as an ear of corn, of good height and figure. Her forehead was high, her eyes were blue, her nose straight, with a tendency to turn up at the end, with delicate nostrils; her curving lips were as fresh as two cherries, and she was shy and retiring. She wore a dress of blue cloth striped with white, braced-up Hundsrück fashion. The sleeves of her dress scarcely descended below the elbow, and left her round arms displayed, though somewhat burnt by exposure in the open air. One cannot imagine a creature more soft and gentle or more artless, and I am persuaded that the maidens of Berlin, Vienna, or elsewhere, would have lost by the comparison.