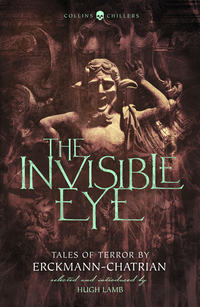

The Invisible Eye: Tales of Terror by Emile Erckmann and Louis Alexandre Chatrian

Père Frantz, seated at the end of the table, appeared very proud of her. Louise placed the cheese and the flask upon the table without a word. I was quite silent – dreaming. Louise having left the room, quickly returned with two plates, beautifully clean, and two knives. She then appeared about to leave us, but her grandfather, raising his voice, said: ‘Remain here, Louise; remain here, or they will say you are afraid to meet this youth. He is a fine young fellow too. Ha! what is your name? I never thought of asking your before.’

‘My name is Théodore Richter.’

‘Well, then, Monsieur Théodore, if you feel so disposed, help yourself.’

He attacked the cheese as he spoke. Louise sat down timidly near the stove, sending now and then a quick glance in our direction.

‘Yes, he is a painter,’ continued old Honeck, as he went on eating; ‘and if you would not mind our seeing your pictures it will give us great pleasure, will it not, Louise?’

‘Oh, yes, grandfather,’ she replied; ‘I have never seen any.’

For some moments I had been cogitating how best I could propose to remain in the neighbourhood and study the environs, but I did not know how to broach this delicate subject. Here was now the opportunity ready made.

‘Well,’ I replied, ‘I desire no better, but I warn you I have nothing very first-rate. I have only sketches, and it will take me a fortnight at least to complete them. There is no painting, only drawing, as yet.’

‘Never mind, monsieur; let us see what you have got.’

‘With great pleasure,’ I said as I unfastened my knapsack. ‘I will first show you the neighbourhood of Pirmasens, but what is that to be compared to your mountains? Your Valdhorn, your Krapenfelz, those are what I should like to paint; those are scenes and landscapes!’

Père Honeck made no immediate reply to this. He took gravely the picture I handed to him, the high tower, the new temple, and a background of mountains. I had finished this in water-colours.

The good man having studied this for a few minutes with arched brows and open mouth, selecting the best light by the window, said gravely: ‘That is splendid – capital; that’s right!’

He appeared quite affected by it.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘that’s the place; that’s well done; one can recognise it all. Louise, come here, look at that. Wait, take it this side; is not that the old market itself, with the old fruiterer, Catherine, in the corner? And the grocer Froelig’s house, and there is the church porch and the baker’s shop. They are all there – nothing is wanting. Those blue mountains behind are near Altenberg. I can see them almost. Capital!’

Louise, leaning upon the old man’s shoulder, appeared quite wonder-stricken. She said not a word. But when her grandfather asked: ‘What do you think of that, Louise?’

‘I think as you do, grandfather; it is beautiful,’ she replied in a low voice.

‘Yes,’ exclaimed the old man, turning to me, and looking me full in the face. ‘I did not think you had it in you. I said to myself, “Here is a young fellow walking about for amusement.” Now I see you do know something. But mind, it is easier to paint houses and churches than woods. In your place I should stick to houses! Since you have begun I should go on if I were you: that’s certain.’

Then smiling at the ingenuous old man, I showed him a little sketch I had finished at Hornbach – a sunrise on the outskirts of the Howald. If the former had pleased him this threw him into ecstasies. After the lapse of a moment he raised his eyes and exclaimed: ‘Did you do that? It is marvellous – a miracle! There is the sun behind the trees; we can recognise the trees, too, and there are birch, beech, and oak. Well, Master Théodore, if you have done that I admire you.’

‘And suppose I were to suggest, Père Frantz,’ I said, ‘to remain here for a few days – and pay my way, of course – to look about me and paint a bit, would you turn me out of doors?’

A bright blush crossed the old keeper’s face.

‘Look here,’ he said, ‘you are a good lad; you want to see the country – a most beautiful country it is, too, and I should think myself a brute to refuse you. You shall share our table, eggs, milk, cheese, a hare on occasion; you shall have the room we keep for the ranger, who will not visit us this year; but as for payment, I cannot take your money. No; I will not take a farthing. Besides, I am not an innkeeper – yet—’

Here the good man paused.

‘Yet,’ he continued, ‘you might, perhaps – after all, I do not like to ask; it is too much.’

He glanced at Louise, blushing more and more, and at length said: ‘That child yonder, monsieur. Is she difficult to paint?’

Louise at these words quite lost countenance.

‘Oh, grandfather!’ she stammered.

‘Wait a bit,’ cried the good man; ‘don’t imagine I am asking for anything very grand – not a bit; a bit of paper will do as big as my hand only. Look you, Louise, in thirty or forty years, when you have grown grey, you will be glad to have something like your young self to look at. I will not hide from you, Monsieur Théodore, that if I could see myself in uniform once again, helmet on my head, and my sword in my hand, I should be too delighted.’

‘Is that all?’ I exclaimed; ‘that’s easy enough, I am sure.’

‘You agree, then?’

‘Do I agree? Not only will I paint Mademoiselle Louise in a large picture, but I will paint you also, seated in your armchair, your musket between your knees, your gaiters and jack-boots on. Mademoiselle shall also be depicted leaning over the chair, and so that the picture may be complete, we will put in that rascal yonder.’

I indicated the dog which lay stretched upon the floor asleep, his muzzle resting upon his paws.

The old keeper gazed at me with tearful eyes.

‘I knew you were a good fellow,’ he said after a short silence. ‘It will give me great pleasure to be painted with my little granddaughter; she at least shall see me as I am now. And if in time she should marry and have children, she will be able to say: “That is Grandfather Frantz, just as he used to be.”’

Louise at this moment quitted the room. The old keeper wished to call her back, but his voice was husky, and he could not. A few moments afterwards, having coughed two or three times behind his hand, he resumed, pointing to the dog: ‘That, Monsieur Théodore, is a good greyhound, I do not deny; he has a good nose and strength of limb, but there are others as good. If you do not mind, we will put the other in the picture.’

He whistled, and the terrier bounded into the room; the greyhound also got up, and both dogs came wagging their tails to rub their noses against their master’s knees.

‘They are both good animals,’ he said as he caressed them. ‘Yes, Fox has good qualities; he has a good nose still, notwithstanding his age. I should wrong him were I to deny it. But if you want a rare dog, look at Waldine there. She has a nose as fine, ay, finer than, the other, she is gentle, never tires, and has all the qualities a good dog ought to have. But this is all beside the question, M. Théodore; what we have to look for in animals is good sense and “ready wit”.’

‘Rest assured, Père Frantz,’ I replied, ‘we will put both of them in!’

Père Frantz then invited me to see my room. I took up my knapsack, and we went outside to ascend to the gallery. Two doors opened upon the balcony; we passed the first, pushing aside the clustering ivy which stretched across the balustrade, and Père Honeck opened the farther door.

One can scarcely picture my happiness when I reflected that I was about to pass a fortnight – a month – perhaps the whole of the beautiful season – in the midst of these verdant scenes of nature far from the busy hum of men.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Для бесплатного чтения открыта только часть текста.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Всего 10 форматов