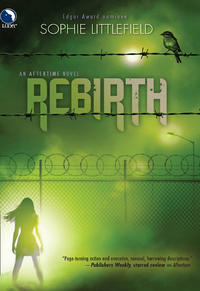

Rebirth

“You won’t be alone. Cass, I’ll tell Faye. I’ll tell Charles. They’ll look after you. I’ll send word if I can, and so will Smoke. We’ll both be back…you need to have more faith in him. He beat them once already—there’s no reason he can’t do it again. He’s well armed and well trained.”

“Your training,” Cass said bitterly. “Your guns.”

As if that made Dor responsible.

A disproportionate number of the citizens who’d survived this long had done so because they had a strong desire for self-preservation along with the skills to back it up. Skills that came from time spent in law enforcement, or in the service or jail or a gang. Dor’s forces were all ex-something—ex-cop, ex-Marine, ex-Norteño…all except for Smoke.

Smoke had told Cass only that he’d been an executive coach Before, and didn’t elaborate in the months they’d been together, always deflecting her questions, turning the conversation elsewhere. Cass hadn’t pushed; she wasn’t ready to tell him everything about her own past, so she hardly felt entitled to demand the same from him.

Smoke’s background may have been inauspicious for survival, much less commanding Box security, but he had some penchant for enduring—plus the legend of the rock slide, which was enough to earn the respect of the others. He’d been a decent shot before joining their ranks; now he was excellent. He’d been fit; now he was hard-muscled and lean. When Smoke slipped out of the tent before dawn to shoot at cans or practice strikes with Joe or put his body through ever-harder workouts, Cass tried to tell herself, He is doing this for us, for our little family, and ignore the fact that he was turning from someone she hadn’t known long into someone she didn’t know well.

“Look, Cass.” Dor looked as though he was going to reach for her again and Cass shrank away from him. “He asked me not to say anything. He’s leaving tonight. He’s… He didn’t want to have to say goodbye.”

Cass made a sound in her throat. Smoke wouldn’t do that, wouldn’t leave without telling her—would he? Smoke, who’d grown more silent with every passing week, whose mind drifted a thousand miles away. Who reached for her less and less often in the night.

“He didn’t want to hurt you more than he had to. I don’t—if he…he just didn’t want to hurt you.”

“Well, it’s a little late for that, isn’t it? He knew damn well he was hurting me—us—he just wasn’t brave enough to stick around and watch.”

She didn’t bother to mask her bitterness, biting her lip hard to keep her angry tears from spilling. She expected Dor to turn away from her, that having tried to mollify her, he would consider his duty done and return his attentions to his own problems, his own imminent journey.

But Dor did not look away, and Cass, whose despair made her want to hit and kick and scream, forced herself instead to think of Ruthie. She thought of her baby and took deep breaths and dug her fingers into her palms until it hurt, until she could speak without her voice breaking.

“It’s time to go back,” she said.

Dor scanned the distant hills, the streets to the right and left. They both listened; there were no moans, no faint cries, no snuffling or snorting. Only the wind, dispirited and damp, made its way down the street, identified by the signpost at the corner of the sidewalk as Oleander Lane. The sign still stood, all that was left of the oleanders that had died the first time a missile containing a biological agent microencapsulated on a warhead built on specs stolen from at least three separate countries came hurtling into the airspace above California at thirteen hundred miles per hour and struck a patch of earth in the central valley, taking out every edible crop for hundreds of miles and quite a few more that were good for nothing but looking pretty.

Even though Dor had warned her that Smoke was leaving, the stillness of the tent reached into Cass’s throat and stole her breath so that she had to grab the edge of the dresser to keep from collapsing. The evidence of Smoke’s absence was subtle but, for one who knew this small space as well as she did, unmistakable. His pack was missing from the bedpost there. His coat—there. He kept his shoes, both the boots and the lightweight hikers, lined up under the foot of the bed, but only the hikers remained.

The photograph of the three of them—the Polaroid Smoke had bought with four cans of chili—was missing from its frame. Cass stared at the frame, an ornate gilt one from a raid—it now held only the stock image of two random dark-haired little girls, laughing as they went down a slide.

Smoke hadn’t even bothered to take the old picture out. The little girls who were long gone now, dead from fever or starvation. Or perhaps they had been victims of the Beaters, their flesh flensed from their bones, left to rot in some garden or forgotten back room. Or the evil of humanity in cold times reached up and took them. Suddenly she was so angry she had to hurt something, had to break something, if only to release a little of the fury from her body. Smoke had left Cass a picture of loss, a reminder of the anonymous grief all around. She picked up the frame—heavy, expensive—and threw it on the ground. But it bounced on the soft rug and didn’t break, so she seized the heavy pewter cup from the table and slammed it into the frame’s glass, splintering and breaking and crushing, sending the shards flying. Cass brought the cup down again and again until she’d smashed dents in the wood and bloodied her fingers, and then she lay down with her face in the carpet and sobbed. She didn’t bother to muffle the sound; people cried here every day. Crying was nothing to anyone who might hear. Her pain was nothing to them. She cried until her throat was raw and her eyes swollen and then she lay still, and when she lifted her head the tent was nearly dark and she lit a candle and spent a long time picking bits of glass from the rug before she left to collect Ruthie from Coral Anne, to fetch her baby because it was going to be just the two of them again in the world, alone for always.

But the morning awoke in her a new resolve. Without Smoke, she had to focus on Ruthie, on creating the best possible world for her daughter from the ruins she’d been given to work with. With Smoke beside her, Cass had been able to make a home of the Box, a family from its battered and motley residents. But now that he was gone, the place’s shortcomings were stark and untenable. The atmosphere of desperation, the leering old men and twitchy hopped-up scavengers. The fact that the only other child here was a shadow-boy, a damaged, elusive little hustler. How much longer would they be welcome here?

Ruthie stirred against her, dream-restless. Cass lay still, reluctant to disturb Ruthie as her resolve took shape. There was no joy to it; her purpose was doleful and raw, but it was better than being empty.

She waited for Ruthie to wake up, considering her new intention, watching the sun color the sky pale blue through the tent’s open window. Yesterday’s bone-deep chill was a memory, practically an impossibility. She was warm under blankets, Ruthie even warmer, her sweet face pressed against the soft cotton of Cass’s sleep shirt. She thought about her plan and it took shape and grew until it seemed to Cass impossible that any other would do.

Ruthie woke and smiled when she discovered that she was in her mama’s bed. She had not spoken again since yesterday’s dream, and Cass wondered if she might have imagined it. But no: Ruthie had said bird. Cass doubted she meant the sparrows that pecked for bits in the dining area. The little brown birds were unremarkable, but other species were coming back. Maybe Ruthie had spotted a redbird or a hawk—something more noteworthy, anyway, than the flock of tiny scavengers.

“Good morning, sugar-sweet,” Cass whispered and covered Ruthie’s forehead and nose with kisses while her daughter laughed without making a sound, her shoulders shaking.

Then it was a matter of choosing their warmest, sturdiest clothes before the two of them went to find Dor to tell him they were going with him.

08

“I MEAN TO GO ALONE,” HE SAID. CASS HAD FOUND him in his trailer, sitting at his desk with a steaming travel mug of coffee, morning sunlight slanting off the tidy surfaces of the cramped space, staring at a spreadsheet on the monitor that was nearly always on. Dor powered his computer with the compact generator that hummed beneath the trailer, and Smoke said he kept digital inventories, as well as some sort of forecasting software and other programs Smoke could only guess at.

Dor had offered her a chair, and Cass had taken it, grateful to be off her feet, Ruthie heavy and dozing in her arms. He’d been pro forma friendly until she’d stated her intentions.

“I can help you. I can give you a reason to be there, in the Rebuilder settlement. One they won’t question.”

“And what’s that?” Dor didn’t bother to mask his skepticism.

“I’m an outlier,” Cass said, pulling up her sleeves to reveal the faint scars still on her forearms. “I was bitten and taken by the Beaters. And I recovered. And the Rebuilders know it. They want me for my immunity.”

After staring at her with a preternatural calm for what felt like forever, Dor spoke softly, like a man who’d just had confirmation that his lover was stepping out on him. “It was your green eyes…yours and Ruthie’s. I’ve never seen eyes like that, so deep and bright.”

Deeply pigmented irises: a distinctive mark of the recovered. In her time in the compound, Cass had caught Dor staring at her a few times, and felt her skin burn at his scrutiny, though he always looked away so quickly that she wondered if she might have imagined it.

Cass often found herself doubting so many of her own perceptions. So much was lost to her damaged memory. And the rest of her that did remember certainly didn’t want to. But now she filled Dor in on the details, leaving out only the existence of Nora.

Almost four months ago, Cass had woken, disoriented and badly scarred from a Beater attack she could not remember, in a field far from any shelter. She had wandered for weeks, walking at night to avoid the cannibals, hiding during the day, her confusion slowly dissipating, until a young girl had attacked her, thinking she was a Beater. But Cass got her blade away and used her as a hostage to gain entry to the school where the girl and her mother sheltered.

The young girl was Sammi. Long before Cass ever glimpsed Dor’s tall brooding form, his inky, depthless eyes, she had made a promise she never expected to have to keep: to find Sammi’s father and tell him his daughter was safe. She had done at least that, and she counted on him to remember that favor now, when she needed him.

Smoke had been at the school, and he had volunteered to escort Cass to the Silva public library several miles away, the last place Cass had lived before the attack. At the time, she didn’t understand how she had recovered, but her only focus was finding her daughter. Discovering that Ruthie had been sent away from the library to the Convent in San Pedro had devastated Cass, but a more immediate problem was that the library had become a Rebuilder stronghold. Its leader, Evangeline, had learned that Cass was an outlier. She said there were a few other outliers like herself, but that they didn’t have enough research subjects yet; the Rebuilders were working on a vaccine and they needed Cass for research and study.

Cass suspected there was more to the story. Evangeline had planned to send Smoke to their detention center in Colima as punishment for his part in the rock slide battle. She didn’t bother to mask her hatred for Smoke, and she barely bothered to conceal her antipathy for Cass despite promising her safety. When one of the men in the shelter helped Cass and Smoke escape, Cass was sure she’d escaped imprisonment in the Rebuilder headquarters, and possibly worse.

“So you know, even if no one there recognizes you from the Box, you’ll be at a disadvantage,” Cass argued, searching Dor’s grim expression for any sign he might acquiesce. “You’ll be just another recruit, with hardly any more status than the people they convert by force from the shelters. I might be able to get more privileges. More access.”

For another long moment Dor said nothing. He didn’t look away, and Cass felt like he was calculating odds and dangers she could only guess at, as though he ran spreadsheets through his mind even when he wasn’t staring at his screens, always focusing on a bottom line that even the end of the world could not erase for him.

“It would be better if we knew exactly what your immunity is worth to them,” Dor finally said, and Cass allowed herself a tiny sigh of relief. It had worked—she had given him something he could understand, a problem presented in the language he was most comfortable with: she could be bartered.

“Yes.”

“And Ruthie…”

“She’s an outlier, too.” Cass didn’t think she could bear to tell him that story—the one before the Convent—of Ruthie being bitten, of the kindness of the woman who nursed her back to health during Cass’s lost months and fever days. “But Evangeline doesn’t know. She doesn’t know about her at all. No one told her, even when Smoke and I were locked up in the library.”

“So how are you going to explain showing up in Colima with her?”

Cass had prepared an answer for that, but she found that it was harder than she anticipated to get the words out. She took a deep breath and rushed through the rest. “We have to say Ruthie’s yours. That she’s your daughter. We have to say that you and I are…you know. Together. All of us. That we met on the road after I left the library, and we’ve been together ever since.”

Dor’s expression barely changed. There was a darkening of his eyes, perhaps, a slight downward pull at the corners of his mouth.

“And why would you be willing to do all of this for me? The risk goes up with every lie you tell.”

“You have it all wrong,” Cass said quietly. “I’m not doing any of this for you. You’re just our ticket to leave San Pedro. I’m not coming with you so much as leaving here. Because there’s nothing left for us here. Ruthie needs to live where there are other children, other…families. And the Box is dying—I can see that.”

Dor nodded as though her answer made perfect sense. “As long as your expectations are realistic. I mean, there is going to be less for everyone, everywhere, and no matter how hard you try, you’re not going to be able to outrun that fact. You’re stuck here, in what’s left of the West. Those lunatics trying to hold the Rockies—they shoot on sight, so that’s not an option.”

“I never said I wanted to go East.” The blueleaf fever that spawned Beaters after the Siege had been limited to California at first, the only state to have spread the mutant seed along with the kaysev that was meant as manna to save and nourish survivors. In a panic that the Beaters would spread across the continent, an increasingly organized army had claimed a boundary along the Rockies, and no traveler who ventured there returned to tell about it. Perhaps because of the barrier, the East had come to symbolize salvation for some.

Cass was not tempted. She would take her chances here, in the ragged remains of California. Somewhere, there had to be a place for her and Ruthie.

“You sound like you’ve lost hope,” she accused.

He narrowed his eyes. “I’m not without hope. I’m just limiting it to me and mine. There will be enough for me and for the people I care about in this lifetime, if I’m strategic about it. It’s not my job to worry about everyone else or any other time.”

“And who exactly do you care about?” Cass tried and failed to mask her anger. She was uncomfortably conscious of her hypocrisy, but she didn’t admit that she had had the very same sort of thoughts herself: Let there be enough for Ruthie—let everyone else starve.

“Sammi. I care about Sammi. And I care about my people. When I’m with them, anyway.” He looked away, his gaze troubled and unreadable.

“What do you mean?” Cass waited, but she could sense Dor pulling away, following the spiral of his thoughts to a bitter place. She couldn’t let him. She had to keep him here, feeling what she was feeling, if there was any chance for her to convince him to take her and Ruthie with him. “Tell me…please.”

For a moment Dor said nothing, straightening the stack of papers on the desk until it was perfectly uniform.

“As long as I’m with them I care, but I don’t know how I’ll feel when I’m away. Faye, Joe, Three-High, Feo—all of them, they…mean something to me.” He glanced at her and then quickly away. “Even Gloria. You may not believe me, but I was really sorry when she died. But three years ago I had an assistant—her name was Melissa. She kept my calendar, brought me coffee. Slept with me sometimes. I know that sounds bad, and I’m not asking for your approval—but Melissa and I were good for each other. I think I might have been closer to her than I was to my wife, at the time.”

Cass murmured encouragement. She was always surprised when people assumed that she’d judge them. Cass didn’t feel qualified to judge anyone after the things she’d done, the straits she’d found herself in.

“I don’t know where she is now, of course—but honestly, even before this year we’d lost touch. I mean, I sincerely hope she found happiness, but it never seemed like something worth pursuing. And there’ve been others. My ex-wife’s family, I cared about them, once. Considered her brother to be like my own for a while. Couple guys I went to college with. My uncle Zed, when I was growing up and my old man wasn’t around much. All these people…”

He pinched the bridge of his nose, rubbing the skin as though it hurt. “I’m not trying to be…anything, really. Not cruel or cold. But all these people, they meant something to me, and now they’re gone, and I’d be lying if I said I spent time worrying about them other than the odd thought that comes along. Who can say why? What I’m trying to tell you, Cass—I’m not a person who keeps people close. Those feelings don’t stick to me, not the way they do for other people. But still. I love my daughter. I love Sammi.”

Cass heard the pain in Dor’s voice, and believed him. She guessed that he was one of those men who had only started learning to love when his daughter was born, and was still a beginner in many ways. Was it possible that was as far as he was ever meant to get? If the Siege had never happened, Dor would have continued on indefinitely, trading and dealing, building his financial empire, people coming and going from his life with little thought or consequence.

But Cass had seen Dor in his solitary room. Seen the humble folding chair, stored carefully against the wall. The window from which he watched the world. His exile did not feel chosen, to Cass, but more like a cast-off coat one wears to keep from freezing to death, ill-fitting and unfamiliar.

“I want you to know that,” he murmured, not meeting her eyes. “If you’re really determined to come with me. You can’t expect to mean anything to me. You say there’s nothing for you here. Maybe, maybe not…you’ve made some friends. You have your work, your garden. Safety for Ruthie. I know you probably believe…that you owe something to someone. Other people helped you get Ruthie back, so now maybe you think you have to settle some sort of cosmic debt, that you have to help me get Sammi. But you don’t. I don’t need you. And I won’t thank you. And I won’t care about you. I mean it, Cass—I’ll never care about you.”

Cass nodded and turned away from him. “That’s the way I want it,” she said with as much conviction as she could muster, and wondered which of them was telling the greater lie.

She asked him one favor—to tell no one she and Ruthie were going. She didn’t want to go through explanations and goodbyes. Cass knew this was cowardice, but she also knew she had only so much strength for the journey, and she was not about to start spending it before they even left.

They would leave in the morning. Dor was gathering his security team late in the evening to make plans for running the Box in his absence. By now they must have noticed that Smoke was gone; the Box was not a big place, and it was his habit to check in at the gate late in the afternoon and again after dinner. Cass wondered if anyone would really expect him to return. The probability that fate would turn in his favor, that he would be able to locate the band of Rebuilders who’d burned the school, that he’d take out enough of them to satisfy the blood-longing he carried and survive—these were not favorable odds, and surely they would all know it.

Dor would tell them that he would return soon, also. This, they might believe. People in the Box—both employees and customers—tended to consider him larger than life. In part, this was due to his elusiveness, the way you rarely saw him in the busy paths or eating areas or market stands, but often glimpsed him at the back of gatherings, at twilight or dawn, coming and going from errands he never explained. He met with them one-on-one and in small groups, and his power went unquestioned, but he stayed out of the din and hubbub of the Box for the most part, rarely partaking in the card games and never, that anyone knew, the comfort tents.

Dor was well regarded and even liked by his employees. Certainly he had their loyalty. But Cass suspected that few, other than Smoke, really knew him. In fact, she was pretty sure that few of them even knew he had a daughter, since he never talked about Sammi and had paid his scouts well to check in on the library occasionally and keep their reports confidential.

Dor had proved astonishingly good at procuring things. He traded shrewdly and paid close attention to the needs and desires of his clientele, and when there was a need, he went to great lengths to see it met. When his stores of liquor dipped, he hand-selected a couple of enterprising guys, friends from Before, and turned them into winemakers. He set them up with a yeast starter, knowing that the arms he traded for it were worth far less than the alcohol they’d eventually produce. In an abandoned San Pedro microbrewery he found them carboys and vinyl hose and air locks, and they were teaching themselves to make fairly palatable wine from kaysev.

He’d found marijuana seeds so that Cass could start cultivating them in her garden. Cass was happy to have the challenge and she’d brushed off Smoke’s worries that a recovering alcoholic shouldn’t work in the drug business: to her, the tiny seedlings were just another plant, another tiny miracle, evidence of life’s return.

Dor had even found an old-fashioned four-sided leather strop somewhere, and paid Vincent to sharpen his straight razor with it twice a week so he could indulge his single vanity, a regular and close shave.

All of this added up to an unspoken belief that somehow Dor was immune to ordinary dangers and limitations, and if he announced that it was to the Rebuilders’ stronghold he was trekking, people would assume he had trading in mind. No one would expect him to fail, despite the Rebuilders’ reputation for brutality and one-sided negotiation techniques. Dor was crafty and he was wily, and people would assume he would trade well and come back richer.

No one would know that what he really meant to trade for was his daughter.

Cass had her doubts. Smoke had told her that the arsenal was scrupulously guarded and locked down. There were hidden, off-site stores, but he and Dor continually worried that their supply of ammunition was low, and travelers barely brought weapons to trade anymore. There was talk of trying to forge makeshift bullets, but Dor had yet to find the materials they would need.

So Dor would not be able to trade weapons for Sammi. Also, the Rebuilders were rumored to be drug-and alcohol-free, by mandate of their leaders, and though Cass knew that there would always be a black market for a high, Dor would not be able to make an open trade for his daughter. In fact, any dealing they did would have to be illicit, because no one ever left the Rebuilders once they had joined. And there was no way to visit their headquarters other than by pledging loyalty. It was dangerous, circular logic that the Rebuilders employed in defense of their recruiting practices—once a citizen experienced the security they offered, there would be no reason to leave. And if anyone tried? Well, that was proof that they were imbalanced and guilty of threatening the cohesion of the new society. Guilty of sedition, to be precise. And that was a crime the Rebuilders would not brook.