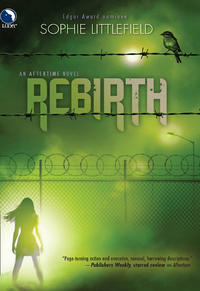

Rebirth

All of this, Cass suspected, added up to be sufficient reason for Dor to accept her offer to accompany him. That—and Cass was not entirely convinced he meant to return to the Box. She knew that he and Smoke had been discussing the possibility that life in Aftertime was about to get several orders worse. Beaters, driven into town by hunger and cold, were growing more desperate and aggressive—and more cunning—so dispiriting losses would continue to mount. Stores were getting thin, raids deadlier, the weather inhospitable. The Box’s bounty would be depleted before spring as trades became scarcer and meaner. Smoke had confided his fears that frequent fights would break out, that the loose system of justice would have to become more rigid, that the chain-link drunk tank in the corner of the Box might have to be upgraded into a true jail. Danger and fear would grow inside the Box’s borders until eventually the dangers within would just be of a different kind than the ones outside.

Cass had been Dor’s observer as long and as attentively as anyone save Smoke. Their unspoken animosity was a thorn that always stung, whether she glimpsed him watching her, hands in pockets, as she tended her garden or whether he stopped by their tent in the evening after dinner and asked with exaggerated courtesy if he might borrow Smoke for a few minutes, minutes that inevitably turned into hours of discussion to which she was not privy. Cass told herself that she resented Dor for taking Smoke’s time away from her, but she knew that Smoke went willingly and that he needed the intense focus of his job. She just didn’t know why, and it was convenient and easy to blame Dor…but now that she was entering into her own bargain with the man, it was time for truth only, even—especially—with herself.

Dor was leaving the Box for Sammi. He would likely go elsewhere once he found her, because staying here under deteriorating conditions ran counter to continuing to survive, and survival was something of a religion to Dor, something he did with perhaps more conviction than anyone else Cass knew. When she came here with Smoke, nearly three months back, the Box was perhaps the safest place in all of the Sierras, maybe even all of California. But now was different. Maybe the North would be better, as the Beaters migrated South. Maybe somewhere rural was safer, a farmhouse or a barn set far from the road. Maybe, for all Cass knew, Dor was considering attempting to cross the Rockies, despite his talk.

But Dor wouldn’t tell his employees anything. If there were plans forming and breaking in his mind, he would keep them to himself as he sketched his possible futures and packed for the trip.

Cass would have liked to say goodbye to Faye, and maybe Coral Anne, but she didn’t trust herself not to break down. Friends: it was ironic that it was only now, when the world she’d known had suffered horror upon horror, only weeks from her thirty-first birthday, that she finally had any to call her own. Faye, with her acerbic wit and moments of surprising compassion. Coral Anne, whose generosity ran as deep as her Texas drawl. Only now did Cass realize how much she would miss them. If she got word that Smoke had returned—if by some miracle he managed to outlast his mission of vengeance—maybe she and Ruthie would come back here and resume their life, if the Box were still viable.

Cass paused in her packing for a moment and considered the possibility, giving herself a few seconds, a miserly ration of hope. She could return with Sammi and Dor, and Smoke would be ready to settle down for good, his thirst for blood finally sated. He would set about insulating their tent; she would make stews from the rutabaga and onions she grew in the garden, and rabbits and muskrats trapped and traded. They would play cards with Coral Anne and that couple who had arrived from Livermore, the ones who hung their tent with colorful flags they’d brought with them all this way. Maybe other families with children would come—and she would convince Dor to let them stay. Sammi would help watch Ruthie; she would teach her to play cat’s cradle and in the spring they would plant zinnias and coneflowers together.

When her seconds were past, Cass took the dream and crumpled it, tossed it from her mind like it was nothing, a senseless fancy. Her pack was prepared: a couple of changes for Ruthie, extra socks and underwear for her. A tube of lanolin and one of Neosporin, taken from the safe, among their dearest possessions.

Also in the safe was a letter Smoke had given her last month. It was written on fine stationery that bore the name Whittier P. Marsstin engraved in block letters. Smoke had carefully crossed off the name on each page—all three of them—and written in the careful script of someone mindful of economy, someone who chose each word with care. They were words of love and yet he never used the word love, promises made without ever using the word promise.

Cass had practically memorized the letter, but she left it in the safe and locked it before snuffing out her candle. As she got into the bed, shivering, and enclosed Ruthie’s warm body in the safety of her arms, she imagined the words of the letter already fading from her mind, and soon the sentences and paragraphs and finally Smoke’s entire meaning would be as lost to her as the man himself.

09

SAMMI RODE IN THE BACK OF THE TRUCK WITH the others, pretending to sleep, too afraid to speak. The men who rode back there with them—when did they sleep? Because every time Sammi opened her eyes, their eyes were there, too, dark and unreadable as they waited and watched while the rest of them huddled together for warmth.

Her mother was dead. Jed was dead. Everyone who resisted—even a little—dead, dead, dead. The only reason Sammi was alive was because her mother’s last words were Go with them, Sammi—her name was still on her lips when she’d gone down, blood pouring from the slice in her neck.

Jed had earned a bullet. He’d pretended to go along, helping his brothers support their parents as they were herded up into the truck, holding them up by their arms so they wouldn’t stumble. Stumbling got you killed—at least, that was what had happened to Mrs. Levenson, who didn’t have time to get her cane when the Rebuilders burst into the burning school. She tried to keep up but she kept twisting her hip and falling, making little “oof” sounds when she landed on the ground, and the third time one of the Rebuilders had hit her on the head with his black stick and she twitched and lay still, making no sound at all. Sammi had seen the Rebuilder—a woman, how could a woman do such a thing?—wind up for the swing, and Sammi had played softball, so she knew, from the way the woman brought the stick back and around and down with a crack everyone could hear, that the force must have crushed poor Mrs. Levenson’s skull.

And that was before they were even loaded on the truck.

There had been sixteen of them, in the end. Sixteen alive and thirty-four dead or dying in the burning school. Sammi was numb with horror as the truck ground out of the parking lot and onto Highway 161. Two of the Rebuilders, both men, both young, rode in the back with them. The one with his back to the cab and another who sat on a box, flipping a blade and catching it. It was the same blade he had used on Sammi’s mom and on the others, too, the ones who tried to keep the Rebuilders out of the common room.

An older man drove, and then there was the woman—the woman who had killed Mrs. Levenson. The guard who stared at her, the one with a tiny triangle of beard and a cap with a cartoon picture of a dog embroidered on it—he had made her sit near him and Sammi wondered with a sickening feeling if it was so he could look at her. Because he just kept looking at her. Jed and his family had been made to sit on the other side of the truck bed, and Jed mouthed words at her whenever the guy on the box wasn’t looking, he said I love you and other things Sammi could not understand, and after a while her vision blurred with tears and she couldn’t see his mouth forming words. In between were the rest of the survivors. Arthur. Mr. Jayaraman. Terry and her kids. The ones who were too old, too young, or too cowardly to fight or who, like Jed’s brothers, had someone to protect.

Her mother had died trying to protect Sammi. They hadn’t even wasted a bullet on her death; they’d dropped her to the ground like a sack of garbage and stepped around the pooling blood as though it was distasteful. Her mother’s body was left behind in the burning building; Sammi hoped it burned all the way, to the bones—and that the bones burned, too. She didn’t want the birds to get to her mother’s body; she’d seen what the birds could do, the big black ones that had showed up a week ago and feasted on the carcass of a fat raccoon the raiders had caught and left out in the courtyard for skinning. Better that her mother disappear from earth as Sammi wished she herself could disappear.

Through the long night in the truck, Sammi shivered and wished she’d been killed, too. But she kept hearing her mother’s last words. Go with them. Well, she had, and she regretted it. Even in the dark she sensed the man staring at her. She knew what he wanted to do. She wished she’d done it with Jed first, because at least then Jed would have always been her first. They had talked about it, and Sammi had finally decided she wanted to and Jed had got some condoms. They just hadn’t gotten around to it. They were waiting for a night when they could be alone.

Sammi cried and felt the cold seep deeper inside her and stared at the stars. Sometimes she thought the stars were the most beautiful thing left, maybe the only beautiful thing left in the world. There were so many, it was almost like a thick and sparkling sauce had been spilled across the sky, and Sammi wondered if somewhere out there was a planet whose inhabitants hadn’t messed it up, hadn’t created their own monsters and poisons to kill themselves off.

She found her dad’s star, and almost didn’t say the words. She’d gotten used to the idea that he was dead; her mother said that it was better that way, that wishing for him to be alive was just pretending, and they didn’t have the luxury of pretending anymore; but until this night she had kept her promise. Every night she found her dad’s star and touched her nose with her fingers the way he taught her as far back as she could remember. “Who do I love best?” he used to ask and she would touch her nose with her finger because that meant Me! You love me!—but that wasn’t even the real part of it.

The real part was the star and the thing they said together. Before he left, even though Sammi was fourteen and too old for it, he would always take a break from his study and come find her, and it didn’t matter if she was watching TV, he would wait for a commercial; or if she was texting or painting her nails, whatever it was, he would wait and then they would go out on the deck and he would find the star and they would say it together. Just another way of saying I love you; she knew that now, but when she was little she had decided it had to be the same every time and so it was.

The night her dad left, his SUV packed with his stuff in the driveway, he hugged her hard and pointed to the sky and said the thing. “Never forget,” he said and kissed her nose, her forehead, and then he added, “Okay?” in a way that sounded so sad and tentative that Sammi promised after all even though she was so angry she had been planning to refuse.

Tonight she almost broke her promise because he’d left her and died, and now her mom had died and she was alone, and if that wasn’t his fault, well, she didn’t exactly know who else to blame. So she wasn’t going to say it.

But there the star was, as bright and yellow as it had ever been, and the man stared and she couldn’t see Jed and she wished she was dead…but she whispered the words:

“Star bright, you and me always.”

A few minutes later they stopped the truck so everyone could pee and the man with the beard, the one who stared, jumped to the ground and took them to the side of the road one at a time while the knife man watched everyone else, and when it was Jed’s turn, all three brothers jumped up and attacked the guard who’d killed her mother and broke his neck before the old man and the woman shot them. The Rebuilders wrapped the body of the dead guard in a tarp and lashed it to the top of the cab. They left Jed and his brothers lying facedown on the ground. And the rest of the way Jed’s mother screamed and Sammi was silent and knew she’d never keep any promise again.

10

DOR SCALED THE FENCE ONE LAST TIME, HIS movements quick and practiced, the calluses on his hands almost numb to the wire cutting his flesh. It was important that no one see him go. People would read things into his departure, and that could lead to trouble—looting and fighting, the kinds of things that happened when too many people shared too small a space with no one in charge. If all went well, there would be a general announcement, tomorrow, when Faye and Three-High and Joe and Sam and the rest could control the message, when they could reassure everyone that nothing was wrong, that Dor would soon be back.

He dropped to the ground and melted into the darkness quickly and quietly, and if anyone had been nearby watching they would have had a hard time guessing who had slipped past them in the moonlight.

The meeting had gone well enough. Lying to his team had become both easier and harder as the weeks had turned into months and this thing he started in the spring had grown into the community it was now, in the middle of November, two seasons and thousands of trades later.

The way Dor figured, every trade changed the Box in some small and fundamental way, shifting people’s personal equations of need and loss and rebalancing the entire community’s measures of hope and satiety. He believed that he was doing good, perhaps the most good it was possible to do in these times. But he had also never felt more alone. The more he was respected, the more he was admired, the further away—the more incomprehensible—other people seemed. And being in their midst didn’t help. Paradoxically, the only thing that helped was utter solitude.

He had never shared these thoughts. No, they had formed and refined in private, up in the quiet of the apartment building, as he watched the sun set over the Sierras, the one view that—in the moments when the blazing red light at the horizon obscured the silhouette of the naked dead trees—still looked like Before. He loved to let the burning last rays of daylight blind him, loved the warmth on his face, and most of all he loved forgetting—even for a moment—that he was responsible for so much. He had never meant to let people rely on him, to look up to him the way they had.

At first it was the old instinct that drove him, to buy cheap and sell dear, to work the deal—and yes, perhaps, on occasion the sleight of hand, the scam—to chase the excitement of being the fastest, shrewdest, richest. Before, his clients were never the point—the deal itself was all he cared about. In the columns of numbers were wide-open spaces, races to be run, scrimmages to be played out. His investments quivered and bobbed like skittish ponies, and so what if it was all artificial, he loved the game. Dor played his clients’ money like a conductor coaxing a tremulous crescendo from a woodwind section, relying on instinct as much as skill, chasing the high that came from nailing the trade, so much sweeter when he’d gambled big.

But the currency of the Box had somehow gotten away from him, so that in between the small comforts and cheap highs he dealt favors and forgiveness and loans and compassion. All of it anonymously, with only his most trusted employees acting as his agents, and it came at a cost: Dor had to be ever vigilant, aware of everything going on in every corner. He couldn’t afford to slip; he had to stay strong and resolute to lead and shape the Box because, aside from him, there was no steadying standard for society. There was no system, as there had been Before, to self-regulate.

Dor had a final errand to run, but it wasn’t to the apartment. He’d said goodbye to that place earlier, and if his thoughts had been truncated by Cass’s unexpected arrival, that was all right. An unaccustomed lapse in vigilance, the cause of which did not bear considering—worry for Sammi, no doubt, when he could afford no worry.

When he returned—if he returned—there would be time to mark any deterioration of his little community and repair what he could. He supposed that it would take some time to mend things with Sammi, as well. Teenagers were moody—hell, even before the Siege Sammi’d shown signs of pushing him away, and she’d been acting up at school. Last year she was passed over for varsity softball and suspended over something she supposedly wrote in the margins of an Algebra test.

Was he to blame? Jessica would have had him think so; but she blamed him for everything. Never mind that she kept the beautiful home in the mountains, the cars and clothes and club memberships. It wasn’t enough. The dissatisfied look he’d seen on her face since before Sammi was born—it was there, etched deeper than ever. He hadn’t made her happy. If he was honest, it had been years since he’d even tried.

Ever since the divorce, Dor was the absent parent, the weekend visitor, the bringer of gifts and the merchant of affections, bargaining for his daughter’s attentions. He wasn’t the first man to make that bitter trade, and he accepted it as his due, for leaving them. He’d tried to appease Jessica by padding her support checks, paying the lawn service ahead, covering her insurance for the year. He’d learned to manage his ex-wife and daughter as well as could be expected, and now that Jessica was gone he would learn to manage Sammi again, once they were safe. Maybe the Box wouldn’t be such a bad place for them to get their footing…for a few days she would be a novelty, but his staff were loyal, and they would pick up on his cues and accept her and…hell, maybe she and Cass would form a friendship, maybe Sammi could help her in the garden. Maybe Cass could tutor her, if they could round up some textbooks. It wouldn’t have to be Cass, of course; Coral Anne had taught third grade, or James—he’d coached girls’ softball in high school. Well. Those were details. And Dor knew better than to start focusing on details when the job at hand was still the big picture.

Big picture: things in Colima would go one of three ways. Easily, in which case they would soon be back here. Disastrously, in which case he would die, and presumably others as well, since failure was only an option after exhausting every other one. Or—and this was, of course, the most likely possibility—with difficulty and complications, starting over somewhere new if they got to start over at all. Each deviation from the plan, each small misstep or change of direction, would spiral outward in increasing magnitude, exacting changes he could not predict. A minor glitch could change the course of the entire operation, and this was what seized at Dor’s calm, what impelled him out into the night when he should be resting up for tomorrow.

He walked quickly along the dark street, arcing his flashlight beam expertly, his strides long and sure. He had no particular destination in mind; he purposefully emptied his mind of as much as he could and waited to be drawn by some small signal. Dor did not believe in the supernatural, in psychic energy or parapsychology or anything like that, but he acknowledged that there was a level at which events eluded the senses that he, a human, possessed. On top of that, he believed that God, the One who seemed to have turned away from this ravaged planet, kept an inattentive eye on His creation; He might return at any time.

Dor stayed on the sidewalks, passing landmarks he knew well. The moon was high and round and supplemented the light from his flashlight. There was the Laundromat with its hulking black shapes of washers and dryers silent and still through the broken windows. The Law Offices of Burris and Zieve, the sign curiously intact, gold letters inked on glass. The alley that led to a tiny restaurant where he had once taken a date, the finest restaurant in Silva, Spanish cuisine served on mismatched Limoges by pretty Portuguese sisters…they’d lit candles in iron holders in the alley and decorated it with pots of geraniums and ivy. His date had ordered flan; she’d also given wicked head. Dor didn’t remember anything else about her. Now the alley was choked with dead leaves and roof shingles, shell casings and a crushed bicycle.

Dor looked away.

They kept the close-in streets clean—picking up trash every week or so—but the farther one got from the Box the more the streets resembled the world at large, deteriorating like the set of one of those old Westerns, a ghost town. Dor walked west on Brookside, aiming more or less toward the boat dealership at the corner of Third and Industry; once he got there he would turn right and make a wide loop back to the front of the Box, where he’d enter without bothering to scale the fence. He didn’t care who knew he’d been out wandering, as long as they didn’t follow. The whole walk would take about forty-five minutes and might settle him enough to sleep, if he was lucky. On another night, he might have taken one of his private stash of Nembutals, if it got especially bad. But with what lay ahead he needed to keep his thoughts clear.

A sound off to his right put him instantly on alert. His gun was in hand in seconds, his feet planted and ready to run. It was true that most people didn’t stand a chance in the face of Beaters’ pursuit, but Dor wasn’t most people…most people didn’t train with an army sniper and members of the Coast Guard, the highway patrol and the Norteños. Dor had survived more attacks than he could count on one hand, and he refused to stop his nighttime wandering even with the knowledge that nests lay hidden every few blocks. Beaters usually stayed put at night, their vision compromised by their malfunctioning irises, which let in only a tiny amount of light; they spent the dark hours piled and entwined in their nests of fetid rags, four and five of them at a time shuddering and moaning in their sleep, writhing and slapping at each other as their fevered minds dreamed their horrific dreams.

This sound, as he stood still as stone and listened, was not a Beater’s sound. They whistled and snuffled and moaned and cried, but this was more shrill, almost a cawing. Dor walked toward it silently, a trick he’d mastered.

Around a corner past the old doughnut shop the sounds grew louder and there, in the tiled entrance of an accountant’s office, was a jerking mass of ink-black shapes. A Beater nest. And those were bodies, two of them—that was a foot there, and another, one naked and the other still wearing a boot. There was little flesh on a foot and sometimes a Beater would not bother picking it clean if it was sated. It would leave the body in the nest after tearing the flesh from the poor person’s back and buttocks and arms, the soft skin of the stomach and thighs, until later, until it was hungry again. Then, it might return to chew the tougher and leaner bits from the wrists and the face and ankles.

That’s what had happened here, Dor figured, to the pair of travelers who’d made it almost to the Box. They’d been felled in their last mile by a band of the monsters who’d dragged them to their nest and then, for reasons unknown, left them there half-ravaged while they went back out into the night.

He looked closer, squinting at the shuddering pile. There, crowding the bodies and feasting on the organs, were birds like nothing Dor had ever seen, enormous black carrion birds resembling freakish outsized crows, wings quivering and flapping in ecstasy as they feasted.

Dor watched in silence and queasy astonishment. He had seen a few varieties of birds around the Box, but nothing like this. There were people who greeted the arrival of every newly returned species with celebration. Cass was like that with her plants, and Smoke and the others took delight in bringing her seedlings and roots for her gardens, or packets of seed raided from hardware stores. Word of any animal sightings spread quickly; in the past month alone people had found small striped snakes and potato bugs and lizards, and there were even rumors of a dog who’d made a few appearances at the edge of town, skittish and scared.