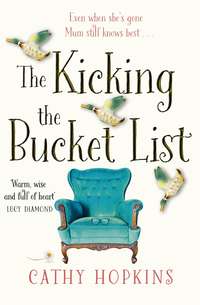

The Kicking the Bucket List: The feelgood bestseller of 2017

‘Dee, you’re the best option,’ said Rose.

‘I am not. Stop trying to control me and take over my life. Both of you are being insensitive to my situation and to suggest I give up my home is the last straw. And anyway, it’s up to Mum. We should ask her what she wants.’

While we’d sulked and seethed at each other, Mum did her research online then went ahead with her own plans. The three of us, smarting from our wounds, withdrew from one another. We visited Mum separately. It was easy enough to do without dragging her into our quarrels, and actually it was nice to have time alone with her when I did visit. I could fantasize that I was an only child. Mum’d reassured me that she was fine about not coming to live with me, or me coming to live with her – she understood and not to feel bad about it, but of course I felt dreadful. I felt I’d let her down when she needed me.

*

Mr Richardson reappeared and handed each of us an envelope. ‘It’s all in there. Do feel free to call if you have any questions.’

‘Thank you, we will. In the meantime, I have to dash,’ said Rose as she put away her phone and got up.

Fleur and I left soon after and went our separate ways. I didn’t mind. Mum might have made plans to get us back together but I couldn’t see it happening, not in a million years.

As I headed for the train station, I decided that after we’d done whatever Mum had requested, I’d have nothing to do with either of my sisters. I had a feeling that they felt the same.

3

Wednesday 2 September, morning

I picked up my bag from where I’d left it when I got home last night and pulled out the envelope that Mr Richardson had given me. As I put it on the bedside cabinet to read again later, I remembered Mum’s request that I talk to God.

I sat on the bed and looked up at the ceiling. ‘OK Mum, no time like the present so here goes. Dear God, my mother’s suggested that I talk to you. I know, it’s been a while – that’s because I’m not convinced that there’s anyone listening and, if there is, speaks English. How does it work? Do you have a Google Translate system on your cosmic exchange for incoming prayers? Er …’ Why am I talking to the ceiling? I wondered as I noticed a damp patch in the left corner above the door. If God is omnipresent then I could just as well talk to the floor. I looked down and there, as clear as daylight, was a message from God, spelt out in cat hairs and toast crumbs. It said, Dee McDonald, your carpet needs hoovering. ‘So … God … I’d be interested to hear what you have to say about wasps and why they exist. And why is there so much trouble and hatred in the world? What do you have to say about that?’

No reply. Just the ticking of the clock by the bed and, in the distance, the sound of an occasional passerby going about their business outside. In the dressing-table mirror I could see a slim woman propped up against a pile of teal blue velvet cushions on a cast-iron bed, a silver grey cat sleeping by her side. Me, dressed in jeans and a pale blue top, chestnut-coloured shoulder-length hair loosely tied back. My roots needed doing. I made a mental note to get some wash-in-colour on my next visit to Boots.

I jumped at the sound of the phone ringing, got up and went to answer.

‘Is that Daisy McDonald?’ A man’s voice. Not one I knew.

‘It is,’ I replied, adopting the same solemn tone.

‘William Harris here. My mother, Eleanor Harris, was your landlady.’

‘Was?’

‘Yes. I’m sorry to be the bearer of bad news but am calling to inform you that she passed away last week.’

I sank back on to the bed and listened to the rest of what he had to say, whilst at the same time trying to quell my rising panic. Letter in the post to me, confirming it all. Oh god, I know what that means. He’ll want me out, I thought as I made myself focus.

When he’d finished, I put the phone down. Mrs Harris had been elderly so it was a call I’d been expecting and dreading for a few years. Hard to take in now that it had actually happened. I didn’t know her well, but it was a blow all the same. We’d met when I first came to the southwest just over twenty-eight years ago, fresh out of art college, my head full of dreams of a studio by the sea. She came to my first exhibition in the Clock Tower down by the bay and liked my paintings. When she heard I was looking for somewhere permanent to live, she’d offered me a house at the back of the village. I could hardly believe my luck when I saw it, especially as the rent she asked for was ridiculously low considering the size of the place and the location. It was a mid-terrace with three floors, a loft up top with great light where I used to do my paintings, two bedrooms on the first floor with an ancient but adequate bathroom, a kitchen, living room, loo on the ground floor, and at the back was a wrought-iron veranda that led to a small neglected garden that I’d brought back to life over the years, planting roses, lavender and wild geraniums.

Mrs Harris said that all she wanted was a good tenant, a caretaker. She wasn’t bothered about getting the best price, as long as the house was looked after. It had belonged to her parents and was still full of their dark mahogany furniture, faded velvet curtains and threadbare rugs. She’d grown up there, so wanted it to go to the right person, someone who was going to stay in the area; not a holiday let, which would mean never knowing how long anyone was going to stay or who they were. The house, though smaller, reminded me of my old family home so I felt like I belonged there from the start. It worked well. I rarely saw her because she lived in Truro and visited once a year, when she’d come in June and nod appreciatively at my roses and the fact I hadn’t tried to change the décor. I paid my rent into her account on time, kept up with repairs, and filled the house with books, artefacts from my travels and friends’ paintings, giving it a cosy, bohemian and lived-in feel. It was my home. Mrs Harris’s death would mean the end of our arrangement.

Wednesday 2 September, afternoon

‘Dear God, me again,’ I said, as I hacked down shrubs in the back garden as if it might solve my problems. ‘Sorry we got cut off this morning. Life took over, I’m sure you understand, being omniscient and all. Anyway. Home. I might not have one for much longer. Can you help? Or should one not put in personal requests?’

As if in response, the phone rang. I ran in to the kitchen to answer. ‘Hello.’

‘Is that Dee McDonald?’ A man’s voice again. Well spoken. Not William Harris.

‘It is.’

‘Michael Harris here.’

Ah, the elder brother, I thought. I’d met him once briefly, years ago, when he was passing through on his way to visit his mother. He was about my age, a handsome, solid-looking man, and very sure of himself in that way the privileged and privately educated often are.

‘Sorry to spring this on you, but I’m just round the corner and I … I believe my brother called.’

‘He did. I’m sorry for your loss.’

‘Thank you. I … Would it be convenient to drop by?’ Christ! He and his brother don’t waste any time, I thought as I caught sight of myself in the hall mirror. I was wearing my gardening clothes, had no make-up on and looked flushed from the exertion of weeding. I brushed back strands of hair from my face with my free hand, then rubbed away a smudge of earth from my forehead.

‘I won’t stay long,’ he continued. ‘But I’d like to speak with you rather urgently.’

I hesitated for a moment, then decided: best get it over with. ‘Sure, just give me five minutes.’

I raced to the cloakroom, splashed my face, applied a slick of lipstick and smoothed my hair. Why the effort? I asked myself. I’d given up on men a long time ago, but old habits die hard, and from what I remembered of my brief encounter with Michael Harris, I’d felt intimidated by him.

On the dot of five minutes, he knocked on the door. He was still attractive: eyes the colour of polished conkers, a full head of sandy hair flecked with grey. He looked a kind man, the type who could be relied on, probably due to his tall stature and broad shoulders. He’d put on a bit of weight around his middle, which I felt gratified to see. It made him look more approachable.

‘I expect you’re calling about the house,’ I said as I let him in and ushered him into the front room.

He nodded as he looked around, appraising the place. ‘I’m on my way to Truro. Funeral arrangements and so on.’

‘Of course. I’m so sorry … my condolences. I …’

He nodded again briefly and I got the impression that he didn’t want to talk about the death of his mother. ‘I’m sorry not to have given you more notice, but my brother called me to say he’d spoken to you earlier and as I was driving this way I …’ He had the decency to look faintly embarrassed. ‘I wanted to call in. I know it’s been your home for so long but—’

‘I can pay the rent if you give me your details. I’ve never missed it.’

‘I know. It’s not that. I … that is my brother and I, now that our mother has passed, well, we’ll be putting the house up for sale. I know William has put it all in a letter but I felt that was rather formal in the circumstances which is why I thought I’d take the opportunity to speak to you in person.’

‘Circumstances?’

‘You having been here so long.’

My stomach constricted. This was my worst nightmare, but I did my best not to let my reaction show on my face. Of course, they want their inheritance. The house must be worth at least five hundred thousand. Can’t blame them, though he doesn’t look short of money, I thought as I took in the navy cashmere pullover, well-cut chinos and brown leather brogues. Michael Harris had a gloss about him that said he lived well. He smelt expensive, too: Chanel for Monsieur. I recognized the scent, woody with a hint of citrus. It had been Dad’s favourite. Mum had kept a half-used bottle of it for years after he’d died. The familiar fragrance always stirred up sadness – as if Dad was there for a moment, but of course, like the cologne, the scent of him soon evaporated into nothing, leaving me with a sense of emptiness at his absence in my life and a longing for something or someone to fill it.

‘I wanted to let you know that we’ll give you first option on the sale,’ he continued, ‘that’s the least we can do.’

I laughed and Michael looked at me quizzically. It struck me that if Mum hadn’t made the condition that delayed my inheritance for a year, I’d have been in a position to buy the house immediately. However, I didn’t want to tell him about Mum nor the will, not until I’d had a chance to talk things over with my friend Anna.

‘I am sorry,’ he said again.

‘I’ll have to go over my finances. Can I get back to you?’

He looked surprised. ‘Of course, er … in the meantime, we need to have the house valued – estate agents. Only fair to you and us. We’d want three valuations.’

‘That would be sensible. Just let me know when they want to come.’

He glanced, disapprovingly, I thought, around the living-room artefacts. There were rather a lot of them and most of them had a story – a memento from a holiday or a gift from a friend. His glance rested for a second on the bronze Greek statue with an oversized penis on the mantelpiece. Anna had given it to me five years ago after a date had gone disastrously wrong and I had told her I was giving up on men. Anna brought the statue to make me laugh. And it did.

‘Satyr with penis rectus, a classic example of the ithyphallic. Some say it was Dionysus, others that he was one of the wood satyrs said to have been a companion,’ said Michael. ‘In contrast to the sleek beauty of so many Greek statues, its vulgarity conveys a strong image, don’t you think?’

Stuck-up prick, I thought, then almost got the giggles when I realized how apt that was in the circumstances. ‘Also known as the wahey, look what I’ve got,’ I blurted. I don’t know what made me say it, but he had sounded so pompous.

He didn’t laugh or ask to look around any further, and I was glad to see him to the door.

‘I’ll be in touch to arrange valuations,’ he said after he’d taken my email address and I his. He made his way through the small front garden and out to his car, a black Jaguar which was parked opposite, outside Anna’s cottage. Before he got in, he turned back to take another look at the house, but saw me still standing on the doorstep. ‘Er … good to have met you again.’

Yeah sure, I thought. You just want me out and your money in the bank. ‘And you,’ I said and gave him my most charming smile. With knobs on. Greek ithyphallic ones.

*

I went through to the kitchen, sank into a chair and blinked away tears. This wasn’t my home any more, it belonged to the Harris brothers. My ginger cat, Max, stared at me from his place on the windowsill. An image of the Buddha looked down at me from one of the many postcards and photos I’d pinned to a notice board next to the cooker. He was half smiling, eyes closed, his expression serene. Smug bastard, I thought. I don’t suppose you had to pay rent for your spot under the banyan tree.

A montage of my life was pinned up on the board: my daughter, Lucy, as a toddler in a red bathing suit, paddling in the sea in Goa, again at nine years old dressed as Charlie Chaplin for a fancy dress party, a wedding photo with Andy, my first husband and Lucy’s father – the twenty-four-year-old me at our wedding wearing a crown of cream rosebuds. Another photo showed Nick, handsome, adventurous, the free spirit. Everyone had adored him, but neither family life nor commitment were for him – at least not with me. Halfway down the board was a photo with someone cut out – that would have been John, my last partner. We were together for six years until I had an epiphany at a dinner party. He was a well-regarded local artist and was rattling on in his usual superior manner and it was like the blinkers came off and I saw him for what he really was – a pompous bore who had sponged off me all the time we were together. I later found out that he’d never been faithful. Back then I took the prize in the ‘Love Is Blind’ contest. I’d had a symbolic cutting up of all his photos, then I’d burnt them with Anna’s help. I’d felt like an old witch as I watched his self-satisfied face shrivel and disappear into flames then ashes.

Further down the board, there was a photo showing my cats, Max and Misty, wearing Santa hats; lots of photos of Mum over the years, some in fancy dress – she loved to dress up for any occasion. She wore reindeer jumpers at Christmas, dressed as a fairy princess on birthdays, the Easter bunny in spring and, one Halloween, she put a sheet over her head and pretended to be a ghost. I was only six and screamed the place down. My dear mad mother. Other photos showed friends at barbecues, dinner parties over the years. Most of the photos were taken at No. 3 Summer Lane: my home, my safe place, through good times and bad.

It isn’t just the house I love, I thought as I gazed out of the window, it’s the whole area and the people in it. I knew everyone, was friends with most of them. I couldn’t go out to the postbox without meeting someone for a chat and a catch-up. We were a community who supported each other through all weathers.

I fell in love with the Rame peninsula the first time I came to attend a music festival up on the cliffs. It’s a hidden gem just over the River Tamar on the other side of Plymouth. There are the twin villages of Kingsand and Cawsand, both picture perfect, with narrow lanes lined with cottages painted pink, blue and ochre, leading down to the three beaches in the bays, all easy to get to for holiday-makers wanting an ice cream, pub or pasty to follow. On the other side of the peninsula is wild, unspoilt coastline with beaches that are harder to reach without a long climb down a winding cliff path. At a third point is Cremyll, where the small passenger ferry docks. It’s a wonderful way to enter the area, the boat chugging in through the yachts moored on the Plymouth side, to see the stately home of Mount Edgcumbe up on the hill with lawns in front stretching down to the sea.

‘Dear God,’ I said. ‘I need five hundred thousand pounds and I need it fast.’ I turned to Max. ‘Where am I going to find money like that in the next few weeks or months? I can’t wait a year until I’ve fulfilled Mum’s requests whatever they may be.’ Max blinked and turned away. God was probably bored with requests like that too.

At least I had the presence of mind to ask Michael Harris for time, I told myself. I’d learnt the ‘can I get back to you?’ trick years ago from Rose though, being the people-pleaser I am, usually forgot to put it into practice. I didn’t need to go over my finances at all. I knew exactly what I had – four hundred pounds in the bank. I had a part-time job teaching art at the local secondary school and I ran workshops in the evenings in the winter months. Both jobs paid a pittance. I earned enough to pay my bills and, with the occasional painting I sold, have some sort of a life. Though in recent months, I’d had no new ideas or inspiration to do my own work. I had no pension plan or savings either; like so many of my generation, we thought we’d never get old. Of course, I’d get my inheritance in a year if my sisters agreed to go along with it but would the brothers Harris wait? Somehow I thought not.

4

Wednesday 2 September, late afternoon

‘Genius,’ said Anna when she’d finished reading Mum’s letter. ‘Have you any idea of what you’ll have to do?’

We were sitting in her kitchen and catching up over a pot of Earl Grey tea. Like me, Anna had been out gardening and was dressed in an old T-shirt and jeans, her short dark hair tucked away under a blue and white polka dot hair band. I’d known her since art college and been friends ever since. She shared my love of Cornwall and when the cottage opposite came up for sale ten years ago, at the same time she was separating from her husband, she didn’t waste any time buying it with her divorce settlement. Her proximity was one of the many reasons I didn’t want to move. I couldn’t imagine life without her. We even had keys to each other’s house so we could drop in on each other anytime.

I shook my head. ‘None. Just that we have to meet some man that Mum hired as a PA to organize it all. He’ll give us our instructions at the beginning of every other month.’

‘Starting when?’ she asked as she cut a slice of her home-baked lemon drizzle cake, put it on a plate then handed it to me.

‘Next month. October. Mr Richardson will let us know where to be, when and what with, then this mystery man will take over.’

‘Exciting.’

‘God only knows what she’s devised for us all.’

‘I can just imagine her glee when she was thinking this up. How’s it going to be funded?’

‘All taken care of from funds from the sale of the family house.’

‘So while you thought your mother was living a quiet life and letting you get on with yours, she was busy scheming up a “kicking the bucket list” for her wayward daughters.’

‘With the help of her friends, Martha and Jean. Fleur’s already called them to see if she could get anything out of them, but neither will spill the beans.’

‘How are you feeling about it?’

‘Mixed. It was a shock to all of us. Curious to discover what Mum’s planned, but mainly still sad. I miss her so much and can’t bear that I’ll never see her or hear her voice again.’

Anna looked wistful. ‘That never goes away.’

‘And I feel bad I didn’t get up to see her more often.’

‘You went every six weeks. She understood – distance, money.’

‘Rose dropped in twice a week.’

‘Well she could, couldn’t she? She lives in London. Don’t beat yourself up about it. Guilt is a waste of energy.’ Anna glanced back at the letter. ‘Have you been talking to God as she requested?’

I smiled. ‘A couple of attempts. I asked where I was going to get the money to buy the house but I reckon if there is a God, he’d think I have more than many and should be grateful.’

‘Possibly but remember that quote from Matthew in the Bible? The one about not worrying about your life? “Look at the birds of the air, that they do not sow, or reap nor gather into barns, and yet your heavenly Father feeds them. Are you not worth much more than they?”’

‘That’s exactly the sort of thing Mum would have come out with. She was always sending me happy quotes in her last few months. She had one for every occasion, as for your Bible lines, if you lived with two cats and saw what they brought in, that would be the end of the “look at the birds of the air” theory, because they’re not in the air, they’re lying dead on my kitchen floor with their heads chewed off.’

‘Cynic,’ said Anna. ‘Do you think your sisters will try talking to God?’

‘Fat chance. Rose is an atheist and Fleur thinks she is God.’

Anna laughed.

‘Mum hated me saying anything critical about either of my sisters. She refused to acknowledge that we’d fallen out or that we only spoke to each other if completely necessary. She always chatted away about Fleur and Rose as if nothing had changed between us, and gave me their latest news and what was happening with Rose and her writers in the publishing world, how Fleur’s property portfolio was going. I’d nod and listen and imagined that Rose and Fleur did the same.’

Anna pointed at the letter. ‘She might not have acknowledged it to you but clearly she was more than aware how things were with you and your sisters hence this brilliant plan to get you back together. She’d obviously been doing a lot of thinking and scheming in her last months.’

I nodded. ‘Her letter reflected a lot of what was going on in her head before she died. She was death obsessed. On my last visit to her, she said she was researching what she could about the next stage of the journey. Where we go when we die, what life’s been all about, that sort of thing. She said she wasn’t afraid and was convinced that there’s something after life, something good.’

‘We’ll probably have the same curiosity when we’re in our late eighties. When I was in India in my twenties, I asked a guru if there was an afterlife. “Only one way to know for sure,” he replied. “Die and find out.”’

‘Sounds like good advice. Mum was never what I’d call a religious person in a church going sense but she was spiritual. On her shelf, she had a wide range of books – the Bible, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Bhagavad-Gita, Richards Dawkins, There is No God, all Elizabeth Kubler Ross’s.”

‘She was always open-minded, wasn’t she?’

‘She was, right up to the end. She had great attitude and embraced death’s inevitability with the same enthusiasm she did every other part of her life. Last time I went to see her, it was like listening to someone who was making holiday plans, checking out the reviews of the destination before they set off. She said it would be like an adventure, like going to the airport, aware she was off somewhere, just not knowing where.’

‘Knowing that she wasn’t afraid must give you some solace.’

Tears welled up in my eyes. ‘Sometimes. Some days I think I can handle it; other days I can hardly breathe and don’t want to see anyone or do anything.’

‘Of course there will still be times like that. It’s only been a couple of months since she died. Grief is like standing on the edge of the ocean. Some days, the water laps around your feet; you know it’s there, it’s manageable. Other days, from nowhere, it blasts in like a tsunami and knocks you right over. They say it takes two years to even feel normal again.’

‘I can’t imagine ever feeling normal again.’

‘You will, although you’ll probably always feel her loss. I know I do of my parents.’

‘A day doesn’t go by when I don’t think of her. I catch myself thinking, oh I must tell Mum that, or see a programme in the TV guide that I think she’d like, or hear an interview on Radio Four and think I must give her a ring – then I remember, I can’t. I miss that she’s not there to talk things over with – like now, the fact that I might lose my home and so have no place to curl up and hide away on the tsunami days when I miss her most. She’d have been so reassuring. She always had such good solid advice to give. I miss that and her kindness and care.