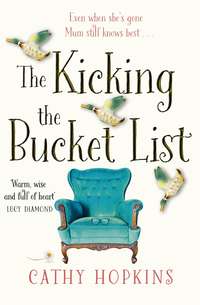

The Kicking the Bucket List: The feelgood bestseller of 2017

Mainly, though, I’m in awe at Mum having thought up her plan for us and never saying a word. I need the money, yes, but it’s not just that, in fact, even thinking about that seems mercenary. I mainly want to do this list of hers because it will give me some extended contact, in the sense that she’s gone but left this legacy, mad though it may be.’

‘And you will get your inheritance in the end.’

‘Not necessarily. There’s no guarantee that one of my sisters won’t refuse to take part or back out at some stage. In devising her plan, Mum’s made me completely dependent on the two people I’d choose not to need anything from. That’s the bit I’m not happy about, and I’m pretty sure they feel the same.’

‘Clever old bird,’ said Anna. ‘She was right. How could any of you refuse to carry out her last wish? You never know, it could be an adventure.’

‘With Rose and Fleur? I doubt it. More like one long argument. Rose can be quite contrary when the mood takes her and Fleur isn’t always easy either. If it was with you, it would be different. But the bottom line is that it was Mum’s last wish. This condition mattered to her and so it matters to me. I want to do it for her.’

Anna reached out and squeezed my hand. I felt a rush of affection for her. It had been her who’d picked me up the day that Rose’s husband, Hugh had called to tell me that Mum had died of a massive heart attack. I never knew anything could hit so hard and went to pieces, numb with shock and disbelief. Not that death was new to me, of course it wasn’t – aunts, uncles, cousins, friends had all gone over the years. My father had died when I was aged six and though too young to really understand at the time, I mourned for him and what could have been rather than what was. With other deaths, I felt for their family and close ones rather than how it affected me. It all depended on what the person had meant. Mum was not only my mother, but one of my favourite people on the planet and with her passing, I felt that my heart had broken. Well meaning friends called, brought cards and flowers, those that had known her offering condolence or advice. But what could they say? In the days immediately after her death, I felt full of cut glass and it hurt like hell.

Anna had nursed me like a child, bringing food, dealing with post and emails.

Some mornings I’d wake up, feel normal for a brief moment, then remember Mum had gone for ever and weep. It was so final. I’d never see her dear and familiar face again, see the kindness and concern in her eyes, hear her voice, her laughter, have her there to turn to.

Anna had understood. ‘The loss of a parent is immense and the pain you feel at their passing is exactly equal to what they meant to you,’ she told me. ‘If you loved someone deeply, you will suffer deeply. Don’t deny it, suppress it or feel you should get over it; feel it and know it is evidence of how much you loved her.’

On the bad days, I would lock myself away and pore over photograph albums just for a glimpse of Mum, something to hold on to. I wore an old cardigan of hers that she’d left behind after one visit and inhaled deeply to try and catch the scent of her. I called her mobile to hear her voice and the message she’d recorded that she’d thought was so hilarious. ‘Hello. Iris Parker here, I’m avoiding someone I don’t like. Leave me a message and if I don’t call back, you’ll know it’s you.’ I found and read everything I could about life after death in the hope that somewhere she continued and that, although her body had gone, her consciousness and spirit lived on. But mostly I was aware that the phone no longer rang. She’d gone somewhere I couldn’t follow and she wasn’t coming back.

5

Friday 4 September

I was in the front garden, enjoying the sun on my bare arms and face when Anna appeared at the gate. She was wearing a peacock blue vintage halter-neck dress, a chunky green glass necklace and her hair was glossy from blow-drying.

‘Why are you all dressed up?’ I asked.

‘Lunch with Ian.’

‘Shows off your figure.’

Anna did a twirl. ‘Ta. So. Have you spoken to either of the Harris brothers?’

‘I have. I decided not to put it off and emailed Michael Harris first thing this morning to say that I won’t be able to buy the house for at least a year. I told him that Mum had died and that I’m going to have to wait for my inheritance to come through. He must have passed it on to his brother William because he got straight back. As I expected, they aren’t prepared to wait that long and are sending the estate agents in the next few days.’

‘Wow, they don’t waste any time. You’d have thought they’d have understood, seeing as they’re in the same position, having just lost their own mother.’

I shrugged. ‘Yes, but they don’t know me or owe me anything. I’m just a tenant in their late mother’s house. Why should they wait any longer?’

‘Out of the kindness of their hearts and because you’ve been here so long. What difference would a year make? Did you tell them about the kicking the bucket list?’

‘No way. It wouldn’t have helped.’

‘Want me to help you clear up for the estate agents?’

I sighed. ‘I suppose.’

‘It’s not over yet Dee. Houses don’t always sell straight off. First of all, it can take weeks for the agents to do the photos and copy for the brochure, then it has to be approved and so on. And we’re going into the autumn. It’s September. Everyone knows the housing market is best in the spring. See if you can talk them into waiting until next year. Appeal to their business sense. Who wants to buy in the winter down here? You’ve got a good argument, especially being where we are. Everything looks better in the spring – your garden, the area. If they’re prepared to wait a while, it might buy you some more time.’

‘Worth a try I guess, though – as we both know – September and October are fabulous months down here, especially if there’s an Indian summer.’

A mischievous expression crossed Anna’s face. ‘I’ve had another idea. Don’t clear up for the estate agents, nor any viewing you get when it goes on the market. If you can put people off for a year, you’ll be in a position to buy again.’

‘But how? This house is lovely and the area is so picturesque. What could possibly put people off?’

‘Ghosts. Tell them it’s haunted. By your mother or, even better, by theirs!’

I laughed. ‘Good idea.’

‘Or casually mention a problem with the sewage and flooding. We’re near enough to the sea to make people worried.’

‘And we could get the lads from the pub to come over and smoke in the living room. Nothing smells worse than the smell of stale cigarette smoke—’

‘Yeah. Make it smell like an old pub. But best of all,’ Anna pointed to herself, ‘tell people about the noisy neighbours. I’ll turn up the CD player with some obnoxious music and you can sigh in a long-suffering kind of way and say, yes, I’ve tried everything but that woman over the road won’t turn it down. She’s very difficult, I think she has mental problems. She has four kids too, they’re just as bad, the eldest has a drum kit and the youngest is teething, poor thing, cries all night.’

‘Ever thought of writing, Anna? You’ve got a good imagination and you’re right, the options are endless.’

‘Ian and I could pretend we’re drunk and make a racket when you’ve someone booked in for a viewing.’

I sighed again. ‘It’s a good plan, Anna, but you know I’ll never do it. It would feel dishonest.’

‘Oh, forget that. It’s your home. You have to fight for it. You’re too nice, that’s always been your problem. Don’t let people walk all over you. Don’t be such a wimp.’

‘OK. Maybe.’

‘Maybe? I know you won’t.’ Anna regarded me for a while. ‘It’ll be all right, Dee.’

‘Will it?’

‘Course. As I said, it’s not over yet.’

Thursday 10 September

I popped into the local shop for milk and cat food. My days are filled with glamorous events such as this. Sometimes I go a bit mad and buy a tub of organic rhubarb yoghurt, the kind with probiotics. No stopping me when I’m in a wild mood.

While waiting to be served, I listened to customers discussing the good weather we were having, then I spied the display of scratch cards next to the till. Waste of money, I normally think. I’m not a gambler, but there was one for five pounds that had a prize of five hundred thousand pounds. It seemed to be calling to me in the same way that Häagen-Dazs Salted Caramel ice cream sometimes does. Buy me, buy me. I could hear it, clear as day. Someone has to win, I thought as I found a fiver in my purse and asked for the card.

‘Fancy your chances then, do you?’ muttered Mrs Rowley, as she handed me the card.

‘I do,’ I replied. ‘You’ve got to think positively don’t you agree?’

Mrs Rowley grimaced. ‘Not necessarily. I want to punch people who are too cheerful, especially first thing in the morning.’ She was a miserable old sod, but popular in the village because she made the rest of us look like a happy bunch. ‘Let me know if you win and you can buy a round in the Bell and Anchor.’

‘I will,’ I said and turned to go. I glanced at the queue behind me, all of whom had been listening. There were no secrets in this village, and normally I didn’t mind my neighbours knowing what I’d bought or not, but who was first in line after me? Michael blooming Harris, who had an amused look on his face. Damn. He’ll think I’m desperate and he wouldn’t be far wrong, I thought as I shoved the scratch card into my bag. ‘Not for me,’ I said. ‘For my friend.’

‘Friend? That’s good of you.’

‘That’s me. Lady Bountiful. Anyway, back again so soon?’

He nodded. ‘I’m meeting with the estate agents later today. I always like to meet them face to face, know exactly who I’m dealing with.’ He had a very direct gaze, which I found disconcerting, and … was I imagining it or was there a charge of electricity between us? No, couldn’t be. Must be the prunes I had with my porridge this morning. I hated him. He was going to take my home and, besides, men like him went for thirty-year-old blondes with breasts that point north, perfect nails, and who have done fancy cooking courses in the south of France. They don’t look at middle-aged women like me with a body on the slow journey south.

Michael Harris only stood out because there was a shortage of decent men in the village. The only single men around my age were Ned and Jack who pretty well lived in the pub, Arthur who smelt of stale biscuits, Joss and Paul, who spent most of their time smoking weed and, anyway, were too young for me, and Harry, who was a bit of a worry and liked to hang out in the cemetery and flash his bits when anyone went past. Ian was the only decent single man, but Anna had bagged him and had been seeing him for the last year. Luckily he wasn’t my type, so we hadn’t had to deploy hairdryers at dawn over him. Michael Harris stood out purely because of statistics. I dismissed the thought of him being attractive before it could take root and make me feel inadequate.

‘Just let me know when you want them to come,’ I said as I left.

6

Thursday 10 September

When I got home, I went into the kitchen, sat at the table and got out my scratch card. ‘OK God, you’re omnipresent – or, as they’d say in the Godfather movies, you’re connected – so now’s your chance to show what you can do and save my bacon.’ I scratched the card. Amazing! I’d won! Hallelujah. Two quid. All my troubles were over.

The phone rang, disturbing my reverie of what to do with my winnings. It was Fleur.

‘Not good news I’m afraid,’ she said. ‘Rose called earlier. She says she won’t be party to Mum’s condition and is going to contest it.’

My heart sank. ‘Can she do that?’

‘She can but she won’t win. I’ve already spoken to a lawyer friend of mine. He said if she doesn’t have a valid reason to not meet the conditions of Mum’s will, she won’t get any inheritance.’

I groaned. ‘And neither will you or I. We all have to sign. If she doesn’t go along with it, that means no inheritance for any of us. She’s so selfish. She must know what her decision would mean for me.’

‘I know. I’m sorry Dee.’

*

I tried to call Rose but got the answering service. I felt so angry, I went straight over to Anna’s with a bottle of Pinot Grigio and the intention of getting very drunk.

‘Why did Rose call Fleur and not you?’ she asked on hearing the latest.

‘No idea.’ I found wine glasses in Anna’s cupboards and poured us both a large drink. ‘Maybe it was because she knows it wouldn’t be the end of the world to Fleur if she didn’t get her inheritance either. Fleur has her own money and so does Rose. Rose probably knew I’d give her a harder time for not taking part.’

‘They’d seriously let an inheritance like that go?’

‘Maybe, if it didn’t fit in with their plans.’ I knew that finances were hard for Anna too, and the thought of my two sisters waving goodbye to a life-changing sum was hard to take in.

Anna looked at me sympathetically. ‘I am sorry, Dee. Do they know how much you need the money?’

‘Fleur does now. I filled her in when she called about Rose.’

‘Get her to tell Rose.’

‘Rose won’t care. She only cares about herself and her family, and with both she and Hugh being high earners, I guess she can afford to say no. Either that or the thought of spending time with Fleur and me is so abhorrent to her.’

‘But you’re sisters. They can’t be that unfeeling.’

I took a gulp of wine. ‘What I feel or need doesn’t matter to either of them.’

‘Want me to make voodoo dolls of them both and stick pins in?’

‘Yes. No. We haven’t even begun Mum’s tasks and we’re already at war with each other.’

‘You’re going to have to call her Dee. Call her up and tell her how much it means to you.’

‘You mean beg. No. Never. You know what she can be like – what both of them can be like.’

Anna nodded. ‘You mean the funeral?’

‘And the reception. If we couldn’t be supportive of each other at times like that, it’s not going to happen now.’

*

It was back in July. I’d stood outside the open doors of the chapel in the blazing sunshine, Anna by my side, and watched the swarm of people go in and settle into their places. Some had been familiar, the last surviving friends of Mum’s; some family, distant relatives that I hadn’t seen for years. Rose, with Hugh and their two children, Simon and Laura, went in. I remember thinking that Simon would be in his third year at university; Laura, tall like her father, and stunning, in her first year. They’d grown so much since I’d last seen them. Rose was the petite one of my sisters, taking after Mum at five foot three. Hugh had put on weight and, with his thinning silver hair and rotund chest and belly, resembled a plump pigeon. Rose had got thinner and looked strained, but she was immaculate as always in a black dress as well cut as her hair. They didn’t see me on their way in.

Anna nudged me when she saw Rose. ‘Have you spoken to her lately?’

I shook my head. ‘She called a couple of times to talk over funeral arrangements and rub in how she was having to organize it all. Mum wrote out what she wanted years ago, even the hymns and prayers, though she wouldn’t reveal what. She’d said she wanted it to be a surprise and that she might get Jean to sing “Ave Maria”, which she would do magnificently out of tune, and Martha could throw away her walking stick and do some interpretive modern dance, like Marina Abramovi´c, the Yugoslavian performance artist who likes to fling herself at walls in her birthday suit. “That would make the vicar sit up,” she said.

‘And that wasn’t all. She said she might have “Ding Dong, The Witch Is Dead” and an entourage of male strippers to carry her in.’

Anna laughed again, causing an old gentlemen to frown at us on his way inside. ‘I loved your mother.’

‘Despite her jokes, I am sure it will all be dignified and appropriate. Although eccentric at times, Mum had class and knew how to behave in public.’

‘Unlike us,’ said Anna, as the elderly man found a pew but turned and continued to stare.

‘When Rose called, she didn’t ask about my life at all. You’d have thought after so long she’d have had some interest.’

‘And did you ask about hers?’

‘I suppose not.’

‘Then you can’t be too pissed off at her.’

I gave her arm a gentle pinch. ‘She made me feel crap for not sending Lucy the airfare to come from Australia, but she couldn’t have come even if I’d had the money – or maybe she could have but not for long enough to merit the cost of such a journey. Lucy likes to stay for weeks when she comes, have a proper stay. She’s got that planned for next year, after we’ve both had time to save up. I’ll send her what I can towards her fare. I always do. It’s OK for Rose, she and Hugh earn loads between them.’

‘You don’t have to defend yourself or Lucy to me, Dee.’

‘I know. Sorry. Guess we’d better go in.’

We went inside and took our places behind Rose and her family who were on the front pew. None of them turned around.

Fleur hovered at the back of the chapel when she arrived, but was soon ushered up to the end of our bench. Even in the tense atmosphere of the crematorium, people couldn’t help but turn to look at her. Like the rest of us, she was in black, a knee length A-line dress and cowboy boots.

‘Very rock chick,’ Anna commented.

‘That’s Fleur,’ I replied. She looked great, ten years younger than her forty-six years, like she’d been cracked fresh out of a polystyrene pack that morning, her body and legs toned and tanned, blonde hair just past her shoulders, beautifully cut and highlighted and her skin glowing – which was surprising, considering the amount she’d drunk and smoked in her life.

Glancing around, Fleur spotted me and we nodded, polite. Fleur stared at Anna, though. She too stood out in a crowd, but more because of the fuchsia-pink highlights she’d had put in last week. Today her funeral black dress was accessorized with ruby red lace-up boots and a pink pashmina.

It had been strange to see Fleur and Rose for the first time in three years, so familiar and yet so removed from my life now. Both of them looked like Mum and had her blue eyes and fine features, though Fleur was a couple of inches taller than Rose. I took after Dad, with the same honey-brown eyes and height.

‘Do I look like Morticia Addams?’ I whispered to Anna. I was wearing a long black dress and kimono-style black devoré jacket. I’d thought it looked appropriate but, next to my sisters, I wondered whether it was more fitting for a Goth party than a funeral.

‘From the movie? No. More like Lurch,’ Anna whispered back. ‘Stop worrying. You look fine.’

Anna was an only child and never fully got my feelings of inadequacy when faced with Rose or Fleur. They’d both had their place in our family clearly defined. Rose, the eldest, the brains; Fleur, the youngest, and with her perfect heart-shaped face, the beauty. When we were young, Rose was the quiet, studious one – secretive, even. Fleur was an open book, bouncing off the walls with energy and crazy ideas. When Mum talked about me, she’d smile and say, ah Daisy, my middle child; well she’s different, she’s the dreamer. I certainly felt like I was dreaming that day. Saying a final goodbye to Mum didn’t feel possible or real.

‘A good turn-out,’ Anna whispered as she looked around. ‘There must be well over a hundred people here, and it’s standing room only at the back.’

‘I don’t know who they all are. A lot of Mum’s friends have already died,’ I replied.

‘Good,’ said Anna, ‘then she’ll have someone she knows to show her round when she gets to the other side.’

‘Maybe,’ I replied. I was glad that I’d talked about death with Mum and knew that she didn’t fear it. She was always a positive soul, endlessly curious, her nose often in a book and – in latter years – her laptop. She was very computer savvy, Queen of the Silver Surfers, forever googling, ordering on line, booking weekends away in foreign resorts or spas until she was no longer able to travel. Every autumn, she’d signed up to learn a new skill. Over the years, she’d done life drawing, learnt Italian, flower arranging, Indian cookery, tango, yoga, meditation, to name a few. When she wasn’t doing one of her courses, she played piano, painted watercolours, created a wonderful garden and home to entertain her large circle of friends and pursue her many interests. I wished that I was like her in that way, but I knew I’d felt jaded of late, disappointed in some aspects of life which had made me cynical and, at times, rather sad.

Music began to play, Adagio by Albinoni. The hum of conversation faded and everyone stood as the pallbearers began to make their way up the aisle carrying Mum’s coffin. It was covered in masses of white roses and gypsophila, her favourites. It was the most poignant sight I’d ever seen and, with it, the finality of her death hit me hard. My knees buckled and Anna put her arm around me, steadying me.

The vicar took his place at the front and signed that we should all sit down. As I looked at the closed coffin, I felt wracked with grief that I couldn’t see the dear being that was in there for just one more moment. I wished that I’d been with Mum at the end, been able to hold her hand one last time. I told myself again that there was no way I could have made it, but it gave me little solace. Too late, I thought, as an avalanche of emotions engulfed me: guilt, loss, sadness, anger but also, somewhere in there, relief that Mum wouldn’t have to suffer years of decline and incapacity. She’d been frail the last time I saw her, struggling to see as well as walk. ‘Old age isn’t for sissies,’ she’d said.

Rose had asked if I wanted to do a reading but I’d said no. I didn’t think I could have kept it together. Clearly Rose and Fleur felt the same, because it was Hugh who got up and read ‘Miracles’ by Walt Whitman, in his confident public schoolboy’s voice, followed by Martha, the friend Mum had made in the retirement village.

‘Who’s she?’ Anna whispered as she walked to the front with the help of an expensive-looking walking stick. Although elderly, she was a tall, striking woman, impeccably turned out, her hair dyed a subtle ash blonde, her nails a not-so-subtle red.

‘That’s Martha.’

‘She’s fabulous. Looks like she might whack anyone who got in her way with that stick.’

I didn’t know much about her, apart from the fact she’d been a Bluebell Girl in Paris when she was younger, then married a consultant and lived in the Far East until her return to England ten years ago to be nearer her son and daughter.

Martha read ‘A Song of Living’ by Amelia Burr then, finally, Mum’s oldest friend and neighbour, Jean, got up and read ‘Do Not Stand at My Grave and Weep’ by Mary Elizabeth Frye. I’d known Jean all my life; she was like a sister to Mum. I was moved to see the effort it took her to walk up to the front then talk about Mum in her familiar Scottish accent. An image of her as a young woman in tennis whites popped into my mind. Mum was mad about tennis too, and she played most weekends with Jean and her late husband Roy, whilst Rose, Fleur and I sat on benches by the courts and stuffed ourselves with cucumber sandwiches and lemonade. I’d always liked Jean. She was full of life, shared Mum’s sense of humour, but was smart too. As well as bringing up her family, she’d studied gardening, ran a very successful landscape design business and written and sold many books on all aspects of the subject long before it became fashionable. Now here she was, an old lady with white hair, slightly bent with age.

After the reading, she went on to speak fondly about Mum, her sunny outlook, her love of her daughters, and for a few moments she brought Mum’s image, sharp and bright, into the chapel. A memory from when I was little flashed into my mind as Jean spoke of Mum’s lifelong love of pranks. If ever Rose, Fleur or I went out of a room to get something, Mum and Jean thought it hilarious to hide behind the curtains or sofa, so we’d return to an empty room and wonder where everyone had gone. They were still doing it when we were teens, much to our embarrassment.