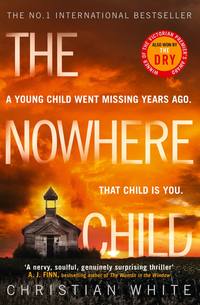

The Nowhere Child: The bestselling debut psychological thriller you need to read in 2019

She stood up suddenly, shaking her head in disbelief. She had to do something about the ants. She set about moving the obstacles that were blocking their path. She kicked away the debris. She found a heavy metal rod and used it to flick away the condom and destroy the cobweb, sending the unseen and wholly imagined spider fleeing into one of the deep cracks between the floorboards.

Emma chewed her lip and waited for her good Samaritan act to pay off.

‘What the fuck,’ she hissed. ‘No.’

The trail had dispersed and was coming apart in places. The ants were disorientated without the broken glass, used condom and cobweb to guide their way. She had removed their landmarks and now their path was lost.

It hurt more than it should have, more than it had the right to, and Emma was suddenly overwhelmed with the urge to cry. No, she wanted to heave and sob.

Dull clarity crept to her then. The magic mushrooms had kicked in. She wasn’t hallucinating or seeing weird colours and lights – Shelley’s cousin had said that might happen – but all her senses felt heightened. It was as if a fog had cleared and she was suddenly aware of the world around her: her body, the carpenter ants, the gristmill, the forest, Manson, the world, the universe.

Tripping was nothing like she had imagined – certainly nothing like the movies. And it was also nothing like smoking weed. This was subtle and wonderful, and she would spend many years to come chasing this first real high. She would look back on the day she took mushrooms in the forest with Shelley as the last true day of her childhood.

Emma unzipped her backpack and found a black marker inside.

As she walked slowly down the stairs she focused on the dirty floorboards beneath her feet, the crunch of broken glass, the wet slap of a puddle, the slippery page of an old porno magazine, the rattle of a discarded can of green spray paint.

Then she was on the ground floor and scribbling a name on the interior wall of the mill.

(‘—Emma, did you hear me? Did you—’)

She stood back to admire her work.

(‘—hear what I said? You need to—’)

Among the dozens, or maybe hundreds of names, Emma had written Sammy Went in neat block letters.

I’m sorry, she thought. Nothing personal. It’s just for the therapy of it.

(‘—Christ’s sake, snap outta—’)

Shelley’s meaty hands clapped onto Emma’s shoulders and spun her around.

‘Did you hear me, Em? Did you hear what I said?’

Emma reached out and tapped the left lens of Shelley’s glasses. ‘You’re beautiful. You know that, right, Shell? Also, can I try on your glasses?’

‘Ah, shit. Are you tripping right now? Ah, that’s perfect. Just perfect.’

As Emma’s focus shifted from the glasses to the face behind them, she saw that Shelley had turned pale. Her mouth was locked in a worried frown, and her eyes were wide and rattled. She didn’t look like Shelley.

‘Listen, Em. You gotta get it together.’

‘What’s wrong?’

‘There’s someone else here.’

‘What? Who?’

‘I don’t know,’ Shelley said gravely. ‘I heard footsteps out by the visitor centre.’

Emma smiled. ‘You’re tripping.’

‘No, I swear.’

‘You imagined it,’ Emma said. ‘It’s the mushrooms. They really are—’

She froze as a shadow moved over the window on the far wall. The glass was cracked, dirty and vine-strangled, but for a brief, startling moment she could make out the shape of a person. Whoever it was slunk away before Shelley had time to turn around and look.

‘What is it?’ Shelley said.

‘I think I saw someone.’

The gristmill door dragged in the dirt as they half-ran, half-stumbled outside. Emma quickly looked back to scan the area where she’d seen the shadow. Nobody was there.

It might have been the mushrooms, but Emma felt quietly terrified.

‘I think I want to go home now,’ Shelley said.

‘Yeah. Me too.’

Step by step, the crunchy leaves underfoot turned to dry soil, to thick grass, to a flat grey sidewalk and finally to the potholed bitumen of Cromdale Street.

Emma knew right away that something was wrong. Too many of the neighbours were out on their lawns and porches, watching her pass. Roy Filly stared out from his open garage door smoking one of his stinky cigars. Loraine Voorhees rocked back and forth in a rocking chair on her porch, a cup of tea in one hand, a mini fox terrier in the other. Pam Grady, resident neighbourhood conspiracy theorist and long-rumoured lesbian, stood on the curb, hands on hips, face knotted with … was it curiosity? No, it was concern.

Did they know she was high?

The strange energy of the street grew stronger the closer she got to home. As she came over the crest that looked down over her house, she saw her father’s convertible parked halfway in the driveway, halfway across the lawn. The driver’s side door was wide open.

She walked faster. Something was wrong. Something bad had happened.

Shelley said something, but Emma didn’t hear it. She was already running. Her backpack was slowing her down, so she threw it off her back and left it on the sidewalk.

Something bad happened.

As she neared the house, the memory of what she’d written on the gristmill wall swept from her mind as fast and as steady as a receding tide.

MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA

Now

I’ve always been drawn to water during turbulent periods of my life. When my dog Shadow died I rode my bike over to Orel Lake and sat on the bank for three whole hours. I didn’t come home until I was all cried out and shivering from the cold. When my mother died I sat alone in my car and stared into Bass Strait all afternoon.

Amy had been furious at me when I finally returned to the hospital, but Dean had understood. He knew as well as I that bodies of water have strange powers, and the larger the problem in your life, the larger the body of water needs to be.

The end of a three-month relationship, for example, could be eased by the amount of water that would fit in your bathtub. A simple shower could cure creative block. But the real stuff, the big stuff, the mother-dying stuff and the maybe-your-whole-life-is-a-lie stuff needed someplace expansive, stirring with energy. So I headed to Dights Falls, a noisy weir built across the Yarra River.

I parked the car and followed a narrow dirt track into the bush. Pine needles crunched underfoot. Although I couldn’t yet see the river through the trees, the bush was alive with the sound of churning rapids, and the air was wet with spray.

The trees arched and parted the closer I got to the river, finally peeling back to reveal a wide landscape, stunning and simmering. I stood looking over the rapids for longer than I intended, wondering what doors I would open by meeting with James Finn again. He had agreed to have lunch with me, and I wasn’t the least bit prepared. I felt mentally off-balance; one nudge from the odd American accountant could send me toppling. Yet what choice did I have but to hear him out?

A lone fisherman was sitting on an outcrop of rocks on the opposite bank. He stood up suddenly, started reeling in his rod excitedly. When he saw his line was empty he deflated, tossed it back into the water and sat back down to wait.

James was waiting at a table near the back of the cafe, nursing a cup of tea and reading from a Kindle. He looked every bit as cold and wooden as when we first met.

‘I’m glad you came,’ he said when he saw me.

‘That’s what she said,’ Dean would have answered, unable to resist the opportunity. It hurt to think of my stepdad, to wonder what he might think about me investigating his dearly departed wife for kidnapping.

I ordered a coffee and we looked awkwardly at menus, even though the last thing in the world I felt like doing was eating.

‘Claire won’t let me drink coffee,’ James said. ‘That’s my wife. She knows how wired it makes me. Hence the tea.’

‘She’s not out here with you?’

‘She’s keeping the home fires burning.’

I opened the menu, pretended to read it, then closed it again. ‘I feel like I should tell you up front that just because I’m here, doesn’t mean I believe you.’

‘Understood.’

‘What I’m saying is my mother’s name is on my birth certificate. And I think I would have noticed if she spoke in an American accent.’

‘Yet you’re here,’ he said flatly. ‘And for the record, accents can be faked just as easily as birth certificates.’

‘Why are you doing this, exactly?’

‘I told you,’ he said. ‘I believe you’re—’

‘Sammy Went, I know. But why are you so interested in her? What’s your angle, I mean? It was nearly thirty years ago. Do you moonlight as a private investigator?’

‘Armchair sleuth is probably more accurate,’ he said. His fingers drummed restlessly on the table. Up until now he had been nothing but confident, measured and a tad robotic. Now he seemed awkward, nervous and a tad human. ‘Like I said, I know the Went family. I was in Manson when it happened. Sammy’s disappearance just sort of … stuck with me.’

My coffee arrived.

‘How did you find me?’ I asked.

‘Let me show you.’ He took a small backpack from the seat beside him and pulled out a manila folder. It was marked, Leamy, Kimberly.

He opened the file and handed me a picture of a face with ghostly hollow eyes and a vaguely familiar expression. It wasn’t a photograph or a drawing, but something in between: an artist’s 3D composite showing a woman with dark hair, a long nose and tightly drawn, lifeless lips. At the bottom of the page was printed, Sammy Went, predicted age 25–30.

‘I commissioned a forensic composite artist to mock that up,’ James said. ‘Based on Sammy’s appearance and family background they determined that this is what she might look like today.’

The composite looked abstractly like me, but if I had committed a crime and police were relying on it to track me down, I could take my time fleeing to New Zealand.

‘I ran that composite through a dozen facial recognition programs comparing it to millions of images online. I got a little over seven thousand hits. I went through each one, narrowed that list down to around nine hundred, and then investigated each one.’

‘That must have taken you forever.’

‘My mother used to say I have the patience of Job,’ he said. ‘The sketch matched with a photo you were tagged in on Facebook, which led me to where you teach. I thought about sending you an email, but I had a feeling about you. A hunch.’

‘It’s a long way to come for a hunch,’ I said. ‘And this is hardly proof. You said it yourself; there were nine hundred faces on your list. And even if what you’re saying is true, wouldn’t I remember something?’

‘Maybe you do,’ he said. ‘Have you ever heard of decay theory?’

‘No.’

‘So, imagine that when a memory is formed, the brain creates a neurochemical trace, so that when you need to, you can retrieve it. Think of it as a big red thread that starts in your consciousness and weaves deep into your mind. When you want to recall a particular memory, you tug on the thread and up it comes.’

As a demonstration, he raised and lowered the teabag in his cup. ‘Simple. Makes sense. But Decay theory suggests that when a particular memory isn’t retrieved over a long enough time period, the thread fades and weakens, and eventually …’ He drew the teabag from his cup and snapped the string in half. The bag disappeared beneath the milky tea. ‘When the thread is broken, the memory just floats around in your brain, untethered, unanchored. You might not think you remember being a little girl in Kentucky, but that little girl might still be up there, in your mind. Maybe she’s figured out how to reach you. Maybe that’s why you’re here.’

I pictured Sammy Went sitting in the middle of a vast black void where all the lost memories find themselves. A red string was tied around her waist, but the other end was slack. She tugged and tugged at the thread, but every time it came back empty, like the fisherman at Dights Falls.

‘That’s not why I’m here,’ I said.

He nodded, tapped the manila folder twice. ‘I know. You’re here to see proof. The smoking gun. Mind if I use the bathroom first?’

While he was gone I stared at my name on the manila folder. He had left it conspicuously on the table. Did he want me to read it myself? If he was right about it containing the smoking gun, then denial might no longer be a viable option.

Ignoring the file for now, I had a snoop through his Kindle instead. In my experience, a bookshelf – digital or otherwise – usually painted a pretty clear picture of the person who stacked it.

Most of the books in James Finn’s digital bookshelf were non-fiction; some history, some war, but mostly true crime. Some of these I recognised – Ann Rule’s The Stranger Beside Me, John Berendt’s Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil and Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood – but there were plenty more I didn’t. There were books about political assassinations, mafia-related crime, celebrity murders, cold cases, serial killings and, surprise, surprise, child abductions.

Oddly enough, seeing all this darkness relaxed me. James’s bookshelf had betrayed him as an armchair sleuth with a macabre curiosity for crime.

Unless …

Scanning fast for Sammy Went’s name, I wondered if he was secretly a crime writer himself. The awkward, cranky demeanour certainly fit. Maybe he was writing a book about Sammy Went and I was his third act.

When James returned from the bathroom he took a deep breath before sitting back down. ‘You ready?’

He opened his backpack. Inside were police reports, maps and files. As he fished through the bag he took out a stack of documents to make room. Sitting at the top of a pile was a list of names under the heading Sex Offenders in Manson and Surrounding Counties. About a third of the names were crossed off, which I assumed meant James had eliminated them as suspects. Others were underlined or circled.

The backpack made me uneasy. This wasn’t just the curiosity of an armchair sleuth after all, and it didn’t look like research for a true crime book, either. This was an obsession.

He took a stark one-page document from the folder and handed it to me. At the top of the page was a small blue logo with Me-Genes printed underneath.

‘What’s Me-Genes?’

‘It’s a genomics and biotech company here in Melbourne. You send them a DNA sample, pay a small fee and they deliver the results. If you pay a little extra you can have those results fast-tracked.’

The bulk of the document was broken into three columns labelled Marker, Sample A and Sample B. Each column contained multiple number and letter combinations, many of which matched. I got the sense I’d need a degree in genomics to read it.

But the part that mattered, the part that made my stomach lurch, was printed in big bold letters at the bottom right-hand side of the page: Probability of sibling match, 98.4 per cent.

‘You’re Sample B,’ James said.

As I began to understand what I was looking at, my skin rushed hot and my whole body trembled with anger.

‘You … You had my DNA tested? How the hell did you even get that?’

‘You were drinking a soda when I first met you.’

‘Jesus. That’s illegal!’

‘It’s not, actually,’ he said. ‘I needed to be sure. That’s why I came out here.’

I lurched back from the table and stormed out of the cafe, feeling like a worm on the end of a hook, reeling back and forth in the current as I waited for the jaws of a hungry fish.

I marched across the street, swung into my car and started the engine. Glancing in the rear-view mirror I saw James. He had come outside and was watching me with his hands stuffed into the pockets of his jeans. His bright yellow sneakers popped against the grey afternoon. Thunderheads rolled above.

‘Goddamn it.’ I killed the engine, got out and walked back over to him. ‘Who’s Sample A?’

‘Kim, listen …’

‘It says I’m a sibling match with Sample A,’ I said. ‘Who is that?’

‘My wife warned me not to come on too strong. I didn’t want to scare you off.’

‘Who’s Sample A?’

‘I am,’ he said. ‘My real name is Stuart Went. I’m your brother.’

MANSON, KENTUCKY

Then

Chester Ellis, Manson’s 64-year-old Sheriff, sat behind his desk reading the Manson Leader. His hometown’s local rag contained highlights from Tractor Day, photos taken at the groundbreaking of the new Christian history museum and a play-by-play recap of the Manson Warriors game – they suffered a demoralising defeat, as usual, at the hands of the Coleman Bears.

It was set to be another quiet day in Manson. A quiet day in a month of quiet days in a year of quiet days.

He turned each page slowly, scanning the headlines for anything of interest. Blitz on blackouts: new project to reduce peak energy use; Manson athletics club finds a home; A new take on old drugs: information sessions help seniors identify addiction.

He arrived at the personals section and found his own ad at the bottom of the second column: Prof. & Athletic African American man with Christian values. Seeks woman for companionship &/or relationship.

Ellis had lost his wife to brain cancer twenty-one years earlier, but with two sons to keep him busy, dating had been the last thing on his mind. Now his sons were adults now, with partners of their own, and Ellis needed … what? He wasn’t looking for a passionate love affair. He wasn’t even looking for love, although if love happened to come along that would be just fine. He was simply looking for someone to share his life with.

Of course, the ad was largely bullshit. He might have been considered ‘athletic’ in his college days, but now all that muscle had settled into fat. The ‘Christian values’ part was a half-truth too. Amelia Turner, who took care of the personals and ran the front desk of the Leader on Fridays, had convinced him to add that part.

Sure, Ellis believed in God and tried his darndest not to cuss too much or hate too much, but Christianity was a pretty wide spectrum in Manson. He sat comfortably and conservatively on the casual, love thy neighbour end. But on the other end sat the people he didn’t want to attract: folks from the Church of the Light Within.

The Pentecostal group – he’d learned the hard way not to call them a sect or, God forbid, a cult – worshipped by handling venomous snakes and scorpions. If rumours were to be believed, they also drank strychnine, spoke in tongues and, according to Tom Kirker after a few too many belts of whiskey at Cubby’s Bar, drank blood and worshipped the Devil.

One of Ellis’s deputies knocked on the door. ‘Sorry to bother you, Sheriff. You got a sec?’

‘Come on in, Beech. What’s up?’

To call John Beecher a man felt premature. Ellis was sure he would be a man someday, but right now he was a pale, near-hairless nineteen-year-old with skin that glowed candy-apple red any time he felt nervous, which was often. ‘A call just came through from Jack Went. As in Went Drugs. His daughter is missing.’

‘His daughter?’ Ellis checked his watch. It was a little after four pm. ‘She’s probably just a little late getting home from school.’

‘No, the little one.’ Beecher consulted his notepad. ‘Sammy Went. Age two. Last seen approximately two hours ago.’

‘Jesus. Get Herm and Louis over there.’

‘Already on their way, Sheriff. Just thought you’d wanna know.’ He looked at the open newspaper. ‘Any takers on your ad yet?’

Ellis tucked the Leader into the top drawer of his desk. ‘Do you remember where we put that book, Beech? That crime scene handbook? Herm and Louis might need it.’

Beecher shook his head.

‘It’s called “crime scene” something. Dissecting a Crime Scene or Crime Scene Deduction … There’s a chapter in there about missing persons; questions to ask, instructions, suggestions, stuff like that.’

‘Oh yeah, like a how-to thing, right? I’m pretty sure I saw that in the bathroom, Sheriff.’

That sounded about right.

Though Ellis’s sons were grown men, he remembered how small and fragile they once were. Jack and Molly Went must be going out of their minds.

‘On second thought, forget the book. Just give me the Wents’ address. I’ll call over there myself.’

Cromdale Street was wide and leafy. All but one of the buildings were big colonial-style homes. The exception was number nine: the Eckles’ house. Ellis eased off the gas as he passed. He remembered it all too well: the leaning mailbox, the NO TRESPASSING sign hung on the fence – which seemed laughably redundant. Who in their right mind would want to trespass on a property like that?

The yard was well-kept – Travis, the youngest Eckles boy, took care of that. But the house was dilapidated and cheaply constructed. Say someone did decide to trespass on the Eckles’ yard, and they kicked in the rattling old screen-door – what then? The only things of value were the brass urn that housed Jeff Eckles’s ashes and the veteran pension cheques his death brought in once a month.

Ellis drove on down the street.

His deputies had arrived ahead of him and left their cruiser’s cherry lights flashing, so Jack and Molly Went’s house shimmered in red and blue against the fading afternoon sun. Ellis pulled in beside Jack’s convertible and started up the path toward the front door.

‘Sheriff,’ came a quiet voice from the porch. A slight figure emerged. It was Emma Went, wearing a grave expression. ‘She’s gone, Sheriff. The sun will be down in a few hours and it’ll be getting cold and Mom doesn’t even remember if she was wearing a sweater.’

Her tone was heavier than any thirteen-year-old girl’s should be. There was something foggy and zombie-like in her movements. Shock, Ellis guessed.

He put a hand on her shoulder. ‘Let’s talk inside.’

Emma showed Ellis into the living room, where Molly Went was slumped on a big red sofa. She was a good-looking woman, even now, with her hair tied into a messy ponytail, and her eyes puffy and wet. A tubby child of eight or nine sat in her lap. Molly’s arms were laced through his, and every few seconds she’d squeeze him like a stress ball. The boy looked uncomfortable but had enough sense to let his mother keep on squeezing.

Deputies Herm and Louis hovered awkwardly. The younger, more athletic Herm was pacing, while the older, calmer Louis rocked gently in place. Both men looked relieved to see the sheriff.

‘Herm, start canvassing the street,’ Ellis said, trying to make his voice sound commanding. ‘Ask if anyone saw or heard anything unusual. Anything at all. No detail too trivial. Check their yards if they’ll allow it, and let me know anyone who won’t. Louis, pull together a search party. We need to check the streets, the sewer drains, the woods—’

‘Jesus, the woods,’ Jack Went said. He was standing by the windows on the far side of the room, drawing back a white lace curtain to peer outside. ‘You don’t think she could have walked that far, do you?’

‘She didn’t walk anywhere, Jack,’ Molly said, squeezing the boy on her lap so hard he made a short, sharp gasping sound. ‘Someone took her. Someone came into our house and took her.’

‘We don’t know that, Molly. Please don’t get hysterical. It’s the last thing we need right now. We have to stay calm. It’s only been—’

‘Hysterical, Jack? Honestly? Our little girl is gone.’

Before excusing Herm and Louis, Ellis took them into the hallway. ‘Leave the Eckles’ place for now. I’ll check in there myself when I’m done here.’