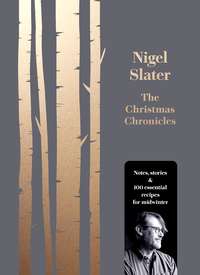

The Christmas Chronicles: Notes, stories & 100 essential recipes for midwinter

Three dried fruit drinks for winter

Apricot, orange and anise

Deep, golden fruit notes here. Rather delightful after dinner, with crisp, dark chocolate thins.

Enough for 20 small glasses

dried apricots – 500g

an orange

whole star anise – 4

brandy – 300ml

granulated sugar – 150g

sweet white wine – 300ml

Put the apricots into a stainless steel saucepan. Using a vegetable peeler, slice thin strips of zest from the orange and drop them into the pan. Add the star anise, brandy and sugar and bring to the boil. Stir until the sugar has dissolved.

Into a sterilised preserving jar, spoon the apricots and star anise, then pour in the liquor (breathing in at this point is highly recommended) and top up with the sweet white wine. Seal and place in a cool, dark place for a good fortnight (better still, a month) before pouring the golden liquor into glasses.

The fruit

Once the ravishing, honey-hued liqueur is finished (and you have dried your tears) you will no doubt want to use the plumped-up fruits for something. My first suggestion is to serve them, whole and fat with alcohol, in a beautiful glass with a jug of cream at their side. Even better, perhaps, is to serve a thick, strained yoghurt with them and a scattering of toasted, flaked almonds.

Figs with maple syrup and anise

Christmas pudding in a glass. Though perfect for Guy Fawkes too if you start it early enough. The remaining fruit – little bundles of joy, soft as a pillow, juicy as a xiaolongbao dumpling – should not be wasted.

Enough for 20 small glasses

granulated sugar – 250g

maple syrup – 100ml

dry white wine – 750ml

dried aniseed – ½ teaspoon

dried figs – 500g

vodka – 250ml

Put the granulated sugar into a medium-sized, stainless steel saucepan and add the maple syrup, white wine and aniseeds. Cut half the figs in half, then put all the figs into the pan. Bring to the boil, then lower the heat and let the figs simmer for twenty minutes, until soft and plump and bloated with wine.

Spoon the figs into a sterilised storage jar, then pour over the liquor. Pour in the vodka, then seal and store in a cool, dry place for three or four weeks, or better still, until Christmas.

The fruit

Later, once the liquid is gone, you would be wise to use the alcohol-laden figs for something. Two or three hidden in the depths of an apple crumble are fun, as they would be in an apple pie. (I often have one or two, straight from the jar, as a treat when I have finished the ironing.) They also make a fine addition to a slice of plain cake, taken with coffee, mid-morning, and served as a dessert with a spoonful of deepest yellow clotted cream. The thick sort you can cut with a knife.

Muscat prunes

You can most certainly drink the mahogany-coloured liquor here, but I really make these marinated fruits as a little extra, something to serve alongside chocolate mousse or milky panna cotta.

Serves 6

prunes – 250g

golden sultanas – 125g

muscat or moscatel – 750ml

Put the prunes and sultanas into a sterilised jar, then pour over the muscat or moscatel. Seal tightly and leave for a month before drinking.

A treat in store

Once you have poured the liquor into glasses, you are left, happily, with a jar full of delicious detritus. You could put the sultanas and prunes into an elegant glass and serve them with a spoonful of vanilla-scented whipped cream and a tiny silver spoon. Or you could spoon the fruit over vanilla ice cream, or frozen yoghurt, letting its syrup trickle down the frozen ice. I wouldn’t exactly say no to finding a pile of these sodden fruits sharing a plate with some fluffy ricotta cakes hot from the frying pan on a Sunday morning.

We can get more adventurous with our little fruit bon-bons, using them to shake up a dish of stewed apple for breakfast; serving them alongside a slice of sugar-crusted sponge cake or with home-made vanilla custard. The wine-drenched fruits can be tucked into the almond filling for a frangipane tart or used in a trifle of layered crumbled amaretti, custard and mascarpone.

Possibly the best idea of all came about quite by accident. After a long day of photography for the book, James and I sat down with a glass of the apricot and fig liqueurs, accompanied by the plumped-up fruits. On the table was some blue cheese – a Gorgonzola, though it could just as well have been Stilton, Stichelton or any of the other blues. We nibbled. The marrying of the blue cheese and the velvety, wine-filled fruits was quite simply gorgeous.

4 NOVEMBER

The joy of stuffing

Goose-fat roast potatoes aside, I consider stuffing to be the most delicious of all accompaniments to the Sunday roast. A sausage meat stuffing made with browned onions, bacon, thyme and dried apricots; a couscous version with red onion, rosemary and raisins; another with minced turkey, lardo – the cured, herbed strips of pork fat from Italy – fennel seed and cranberries. I like my stuffings rough-edged, generously seasoned and deeply savoury. A little sweetness from dried fruits perhaps, but onions and herbs, much lemon zest and black pepper are essential.

There are two ways of cooking stuffing: inside and outside the bird. Each way has its disciples. Roasting the mixture inside the cavity of the turkey or goose means that the juices of the meat trickle down through the forcemeat as it cooks, imbuing the stuffing with the essence of the bird. The downside is that in order to cook the stuffing properly, it may mean overcooking the bird, and, should you pack it in too tightly, the heat will never penetrate fully, thus risking neither the inside of the bird nor the stuffing cooking thoroughly. Dare I mention salmonella?

Cooking the stuffing outside the roast, in the same roasting tin, means there won’t be enough of it, and its presence interferes with the gravy and roast potatoes. It’s pretty much a non-starter. The third way is to cook it separately in another dish. It works from a safety point of view, and you will get tantalising, crusty nuggets on the stuffing’s surface, but this method loses the opportunity of soaking it with the juices from the bird as it cooks. I get round this by spooning some of the fat and flavouring from the roasting tin over the stuffing as it cooks.

Stuffings, forcemeats, call them what you will, have gone out of fashion. I suggest that this is a disgraceful state of affairs. Imagine the flavour in a ball of sausage meat that you have seasoned with sweet golden onions, thyme and rosemary, lemon zest, chopped bacon and juniper, then spooned goose fat over as it roasted. Or a tray of stuffing made with minced turkey, bacon, lemon, parsley and Parmesan you have left rough on top, so the ridges and furrows brown crustily.

I would give up the sprouts, the chestnuts, even the little sausages and bacon of the extended family roast rather than go without generous amounts of stuffing. It is also the icing on the big fat cake that is Christmas dinner. The bit which, if I am completely honest, I prefer to the meat itself.

And, of course, there should be plenty, that goes without saying. But this is not gluttony – there should be enough so that we can eat it cold the next day, cut like a cake and layered with sliced chicken, goose or turkey in a sandwich on chewy bread. And further, I need some to eat with slices of cold roast meat, a potato and spring onion salad and bright purple pickles.

Turkey, lardo and fennel seed stuffing, cranberry orange sauce

On this late autumn night, wet and cold from sweeping up leaves from the garden paths, I make plump rissoles of minced turkey with lardo and chilli flakes for supper. As we tuck in around the kitchen table, we decide that they would make an excellent stuffing too, to be baked around the bird or, more conveniently, in a separate tin. We bought the lardo, the silky white fat that is such a treat served on rough toast with a trickle of olive oil and some crumbled rosemary, from an Italian grocer’s. It’s not difficult to track down. Buy it in a block so you can grate it. Failing that, get it in thin slices and chop them finely. The gorgeous fat will melt and moisten the turkey meat, which has no real fat of its own.

Enough for 4

fennel seeds – 2 teaspoons

minced turkey – 500g

dried chilli flakes – 2 teaspoons

dried breadcrumbs – 60g

lardo – 150g

olive oil – 2 tablespoons

For the sauce:

cranberry jelly or sauce – 3 heaped tablespoons

orange juice – 50ml

orange zest – 2 teaspoons

cranberries, fresh or frozen – 100g

Toast the fennel seeds for a couple of minutes in a dry frying pan, then tip them into a large mixing bowl. Put the turkey mince, chilli flakes and breadcrumbs into the bowl, then coarsely grate in the lardo. Season generously with both salt and black pepper, then mix thoroughly.

Shape the stuffing mixture into 8 large balls, then place them on a tray and refrigerate for twenty-five minutes. Set the oven at 180°C/Gas 4.

To make the sauce, put the cranberry jelly or sauce into a small saucepan and place over a moderate heat, then add the orange juice and zest and the cranberries and bring to the boil. Turn down the heat so the mixture simmers gently and leave for five or six minutes, until the berries have softened a little. You should be able to squash them easily between thumb and forefinger. Remove from the heat and leave to settle.

Warm the olive oil in a shallow pan and fry the stuffing balls, moving them round as each side browns, until they are golden brown all over. Transfer the balls to a baking dish, sitting them snugly together, then spoon over the cranberry sauce. Bake for thirty minutes.

Pears, clove and orange granita

Carried away with their quiet beauty, I seem to have bought rather a lot of pears. I do this with peaches too. And avocados. Damsons as well. Fruits or vegetables caught at a perfect moment. Sometimes, I simply cannot resist. (We will be feasting on pears for a week.)

Today, a refreshing dessert, scented with sweet spices. The timing is tricky, with pears often taking anything from fifteen to fifty minutes to soften. I check them regularly with a skewer as they cook. Pears are often at their most delicious when on the edge of collapse. So tender they require a careful hand to transfer them to the serving plate.

Serves 4

orange juice – 1 litre

caster sugar – 100g

cloves – 4

half a cinnamon stick

pears, large – 2

Pour the orange juice into a non-reactive saucepan, add the caster sugar, place over a moderate heat and leave until the sugar has dissolved, stirring occasionally. Add the cloves and cinnamon stick and bring almost to the boil.

Peel the pears, slice each one in half from stem to base, then scoop out the cores using a teaspoon or, if you have one, a melon baller. Lower the pears into the juice in the pan and simmer gently until soft. Ripe pears will take about twenty minutes, hard fruit considerably longer. They are ready when they will easily take the point of a knife or skewer.

Lift the pears carefully from the pan with a draining spoon and place on a plate. Spoon over a little of the orange juice to keep them moist, then cover and refrigerate.

Chill the seasoned juice as quickly as possible. (Pouring the juice into a bowl, then resting it in a large bowl of ice cubes will speed up matters.) When the juice is cold, remove the cloves and cinnamon, pour into a shallow plastic freezer box and freeze for at least four hours.

When the juice is almost frozen, pull the tines of a table fork through it, roughing up the surface, then digging a little deeper, making large ice crystals in the process. Take care not to mash the crystals too much, leaving them as large as possible. Put the granita back into the freezer.

To serve, put a pear half on each dessert plate or shallow dish, pile some of the granita into the centre and serve immediately. You should have enough granita over for the next day.

5 NOVEMBER

Fire and baked pears

We have been lighting fires around this time for centuries. Since ancient times Celtic people have gathered around bonfires on October 31 and November 1 to celebrate Samhain, the end of the harvest and the beginning of winter. We burn candles in hollowed-out pumpkins on All Hallows, and since 1605 we have celebrated the failure of Guy Fawkes’s attempt to blow up the House of Lords and the protestant King James by lighting fires and setting off fireworks.

The celebrations have changed since I was a kid. Hallowe’en has turned into a pantomime of extortion and petty vandalism dressed up as ‘Trick or Treat’. The rickety piles of branches that stood quietly throughout the countryside, ready to be lit on November 5, are fewer. The back-garden firework parties have very much disappeared too. Spectacular displays and vast communal bonfires are now more organised and often run by local councils and bonfire societies. Traditional effigies are still displayed and burned, occasionally of Pope Paul V, head of the Catholic Church in the time of Guy Fawkes, but more often than not it is images of contemporary villains, Savile, Trump and Farage, which we now set alight. (There are so many I don’t know which to choose.)

The climate seems different too. The remains of childhood fireworks, black with soot, were regularly rescued from spiky grass white with frost. Yet I can’t remember the last time frost coincided with Bonfire Night.

In my part of London the fireworks start mid-afternoon. Barely visible against the milky grey sky, their startling beauty is wasted. At twilight, the cascades of pink, silver and green explode high above, sometimes to cheers of delight. I have never quite understood the draw of fireworks, it all seems a bit of a waste of money to me, but a bonfire is a different matter. The smell and crackle of dry twigs, the flames, smoke and glowing embers have always held a certain magic for me, and I am never happier than when there is a fire in the hearth.

There is no party tonight, no fire lit in the garden, just the occasional glances at a particularly extravagant cascade of lights over the East End. Instead, we sit round the fire eating fat Italian sausages, creamed leeks and beans, and to follow, a bowl of ice cream with searingly hot marmalade pears, whose glowing bittersweet sauce tastes like cinder toffee.

Leeks, beans and Italian sausage

This is one of those good-natured recipes that can be multiplied successfully for large parties, or made earlier and reheated as necessary.

Serves 2

leeks, medium – 3

butter – 30g

water – 100ml

olive oil – 2 tablespoons, or a little pork fat

plump sausages – 4 (400g)

vegetable stock – 250ml

cannellini or haricot beans – 1 × 400g tinned

parsley, chopped – a handful

Cut the leeks into rounds about 1cm in length and wash them in plenty of cold water. Bring the butter and water to the boil in a wide pan with a lid, then add the leeks. Cover with a piece of greaseproof paper, or baking parchment, and a lid. The paper will encourage the leeks to steam rather than fry.

Warm the oil or a little pork fat in a frying pan and cook the sausages, slowly, over a moderate heat. Let them brown nicely on all sides.

Leave the leeks to cook for eight or nine minutes, until they are tender enough to take the point of a skewer with little pressure. Pour the vegetable stock into the pan and continue cooking for two minutes, then tip the leeks and their cooking liquor into a blender and process until almost smooth. (It is important not to fill the blender jug more than halfway. You may need to do this in more than one batch.)

Return the leeks to the pan, then drain and rinse the beans and fold them into the leeks. Stir in the parsley, and spoon on to plates with the sausages.

Marmalade pears with vanilla ice cream

This truly gorgeous recipe is, I suppose, a new take on my baked pears with Marsala (Tender, Volume II) but with a deep, syrupy bitter-sweetness, reminiscent of old-fashioned black treacle toffee. The hot, translucent pears and the glossy apple and marmalade sauce are wonderful with vanilla ice cream. There is a point, after about forty-five minutes, when you need to watch the progress of the sauce carefully, lest it turn to toffee. A non-stick roasting pan is essential.

Serves 4

pears – 3 medium

apple juice – 200ml

orange marmalade – 150g

Marsala, sweet or dry – 1 tablespoon

honey – 1 heaped tablespoon

vanilla ice cream, to serve – 8 scoops

Set the oven at 190°C/Gas 5. Peel the pears (I think you should because the skin can be tough, but it is up to you), cut them in half, and scoop out their cores. Cut each half into three, then place them in a non-stick roasting tin. In a small saucepan, bring the apple juice, marmalade, Marsala and honey to the boil, then remove from the heat and pour over the pears.

Bake the pears in the preheated oven for twenty minutes, then turn them over. At this point they will look decidedly uninteresting, but carry on anyway. Let the pears bake for a further twenty minutes, then watch them carefully. The sauce will be bubbling now, the colour of amber and rising up the pears, almost covering them. Test them for tenderness – a small knife should slide through them effortlessly. They should be translucent and butter-soft. If they aren’t quite ready or if the sauce isn’t syrupy, give them a further five minutes.

Let them rest for five minutes. Serve them with the vanilla ice cream.

6 NOVEMBER

Making gnudi

I sweep up the leaves, most of which I recognise. My parents’ gift of The Observer Book of Trees was clearly not lost on me. There are those of the fig, like giants’ hands; the feather-like golden robinia; the oval greengage and the smaller Ouillins gage, whose tiny leaflets are brown-freckled, like its fruit. There are the green leaves of the Doyenne du Comice pear, with their lichen-like splodges of rust, and those of the Discovery apple that somehow manage to be larger than its fruit. The honeysuckles are crisp already, like the tiny pieces of pork crackling I used to find in a bowl on the butcher’s counter as a kid. And the horse-chestnuts have already found their way over the rooftops from the lane in front of the house. Heaven knows how. Others will stay put for a while – those of the jasmine and rose and white lacecap hydrangeas.

Sweeping the leaves is a thankless task – there will be just as many tomorrow. But better that than the boredom of a lawn. They go into net sacks to rot down. Soaking them, just occasionally with the watering can, helps to speed up the process. Once crumbly, they will be put on to the beds. Leafmould is treasure to a gardener, a bag of gold with which to treat his plants. There is a little science to it, and a wee bit of gardener’s law. Hornbeam, oak and birch, lime and cherry leaves will rot down within eighteen months; horse-chestnut, beech, magnolia, hawthorn, maple and sycamore will take longer because of their high fibre content. A shredder would speed up the composting process, but I really don’t have the room.

After Christmas, there will be the tree to get rid of. Pines and conifers take a good couple of years to rot down and so shouldn’t be mixed with the others. They need to be left in the open and turned regularly with a garden fork. That done, they are best used only to mulch other acid-loving plants such as heather. Having not an inch of garden to spare, it might be more prudent to leave my tree out for the council, who collect and compost them for us.

It is too early, but I have been mulling over what to give the vegetarians for Christmas lunch when we are tucking into our grilled scallops. (I know it’s going to be that because I did it last year, with pancetta and a smooth pea purée, and everyone loved its lightness and savour.) The vague plan is to serve a light pasta dish first, the little pillows of ricotta and Parmesan known as gnudi. My vegetarian friends are not hardcore, so I don’t have to worry about mixing up their Parmesan with my Parmesan.

The gnudi take minutes to make, but absolutely must be dried on a tray in the fridge overnight, snuggled down in a deep snowdrift of fine cornmeal. Skip that stage (always a temptation) and they will dissolve in the cooking water. You will have no gnudi, no dinner. I choose them because they are light, simple and special. They are not hard to make but they do require a light hand. I make them myself because I enjoy shaping them and lowering the flattened balls into the cornmeal almost more than anything else, and anyway, you can’t buy a decent commercial version of them for love nor money.

Gnudi require the hands of an angel. You must treat the mixture of fresh, white ricotta and grated Parmesan as delicately as if it were a Christmas bauble, which in this case I suppose it is. This is cooking with the utmost respect and care, and I love it.

The usual accompanying sauce is something with cheese and cream, though I have had others. My thought is that such a recipe is too rich and heavy for purpose, so I am keen to have a go at something else. In my head are ideas for both a creamy spinach sauce and a sort of avocado sauce, made with lemons, basil and olive oil. The Hass variety of avocado – the one with the crocodile skin – is at its best in the winter. I shall make the gnudi today and have a go at the sauce tomorrow.

Gnudi

My heart sinks when I see a recipe that takes two days, but this is an exception. We are talking minutes of work rather than hours. My gnudi recipe is based on that of the wonderful April Bloomfield, whose own version has become a permanent and much-loved part of her menu at the Spotted Pig in New York. Mine have a little more Parmesan to ricotta than is the norm, and my impatience means they get only twenty-four hours in the fridge. April leaves hers for at least thirty-six (and in the quest for perfection, I’m sure she’s right).

Makes 20 small gnudi, serves 4

ricotta – 250g

a little nutmeg

Parmesan – 40g

fine semolina – 250g or more

Put the ricotta into a bowl. Grate a little nutmeg finely over, then add a very little salt. Grate the Parmesan finely and gently stir in. Have a baking sheet ready, covered with a thick layer of the semolina.

Using a teaspoon, scoop up a generous heap of mixture and make it into a small ball, rolling it in your hands. (A dusting of semolina on your hands will help.) You can leave the gnudi round if you like, but I prefer to press them into a slightly oval shape. Drop the ball on to the semolina-lined tray, then roll it back and forth until it is coated. Continue with the rest of the mixture. You will have roughly 20 little gnudi.

Once they are all rolled, shake the remaining semolina over them, then put the tray in the fridge. Don’t be tempted to cover them. Leave overnight.

None of this solves our own dinner situation. So we go out. I feel somewhat blessed (not to say a wee bit smug) that so many good restaurants seem to be opening up on my doorstep. A dozen cracking places to spend an evening and all within walking distance.

7 NOVEMBER

A trip to the forest, and those gnudi