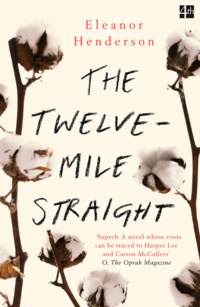

The Twelve-Mile Straight

One sunny morning at the height of summer, a truck pulled up in the dirt driveway and a woman with knee-high boots climbed out of it. Her short hair was yellow as a cornfield. Elma stood barefoot on the porch, fiddling with the pins that held up the great pile of her hair, as the woman made her way up the driveway and reached to shake her hand. Elma feared she was from the home demonstration club or the WCTU, on a mission to save her vegetables or her soul. The woman said, “I’m here to see the Gemini twins.”

Elma let her hand fall, loose as a dishrag. “They’re not Gemini,” she said. “They’re just regular.”

She was a dog breeder on her way to Florida, come all the way from Atlanta. Out of the wooden truck bed, where a dozen dogs yapped, she scooped up two Labrador puppies, one the color of butterscotch, the other oily black as a crow. “They’re called Castor and Pollux,” she said. “Every child needs its own dog.”

Her father came in from the field and thanked her and the dogs jumped on him and he laughed. What was there to laugh about? Elma watched their pink tongues lapping at her father’s hands. This was their reward for killing Genus. Dogs.

“We can’t keep them,” Elma said to the woman. “We got enough to look after with the babies.”

“Course we can,” said her father. “Dogs look after theyselves.”

And he made Elma take the woman into her room, where the babies now shared a larger crib that Juke had built. The woman leaned over the sleeping twins but didn’t pray. “Would you look at that,” she said.

“Please don’t touch the babies,” said Elma. “They’re still fragile. They were born small.”

“They look strong,” said the woman. “Especially this boy here. That’s hybrid vigor.”

Elma joined the woman at the crib, pulling the quilt to Wilson’s chin.

“Most people don’t believe a woman can have two babies from two fathers at the same time. They think it’s witchcraft, don’t they? Or just tales from Bible times?”

Elma felt a sudden pressure in her chest, like a blush, or a rush of milk.

“With dogs in the wild, it happens all the time. You take any bitch in heat, they’s as good a chance as not that every mutt in the litter’s gone have a different daddy.”

“That so?” said Elma, head cocked. One of her pins sprung out of her hair and she bent to pick it up, then took it between her lips, chewing it over.

“Your babies will be fine,” the woman said. “Black or white, they’re fixing to be strong.”

Of course, Wilson wasn’t true black. Nor was he red like Isaac’s child Esau, though under his skullcap was a rusty shock of hair, like the bronze wool used to scrub the pans. When he had grown into his skin, he was a warm, loamy brown, the color of the earth tilled for seed—sand and silt and clay mixed together. And when his eyes finally settled, when he could stare back at the faces that loomed over the crib and hold them in focus, they were a pale gray-green. You didn’t have to look twice, some said, to see those eyes were Elma’s.

Winnafred, though—already she was called Winna Jean, or just Winna—took after her father. When her skin cooled from the pink of infancy, she was white as a gourd, with Freddie’s sun-bleached hair, even before she’d seen the sun. It wasn’t until years later, when the twins spent their days running between the house and the fields and the barn, that their freckles came out, like stars appearing in the night sky. If you wanted to believe they weren’t twins—and at some point, everyone did, even the twins themselves, as often as they wanted to believe that they were—their freckles were there, finally, to connect them, Castor and Pollux joined in their immortal constellation.

When they were still babies, Elma dressed them head to toe, even indoors, even in summer. She wanted to protect them, to hide them, to make them more the same. You couldn’t blame her. After all, Juke said to the visitors, she’d been expecting only one. When she was pregnant, singing “All the Pretty Horses” to the baby kicking in her belly, she’d sewn six identical guano sack dresses, stitching them together with hay bale twine. When two babies came instead, she dressed both of them in the sacks. If she could have, she would have stitched the babies together at the waist, like Siamese twins. Sometimes it seemed she wanted to believe Wilson and Winna were one child, or that she needed others to believe it. It didn’t matter how the babies came to be. Babies were babies. Even Juke believed that.

“Course I love them both the same,” Elma told the women from church, the reporters who tracked white clay across the floor. She followed them with a broom. “All children live in the kingdom of God, don’t they?”

And they nodded with certainty, saying “Amen” and “Praise His name.”

But they were thinking of all the things she might have done with that baby, all the doorsteps she might have left him on in the middle of the night. The colored school. The colored church. In a basket on the creek. She could see the scheming in their eyes, the stories they were writing in their heads. Just like they wondered what had happened between Elma and Genus Jackson in the cotton house or creek or cornfield, a cornfield she hadn’t even been in, but they were following her there.

In some of their eyes, doubt. They had seen their share of mulatto babies. The Jesups were as liable as any country family to have some black blood along their line, black blood that decided to rear up and show itself. (The white Youngs who owned the tobacco plantation and the black Youngs who owned the juke joint? “You think they ain’t kin?” a white farmer, drunk enough, might be heard to say to his wife. This was raised as a diversion, because that white farmer might himself have a favorite colored girl in town, or in a shack, and likely as not his wife knew the girl’s name.)

It wasn’t a miracle, some thought, just a disgrace.

But mostly people believed. Folks in Cotton County were believers. They believed in Jesus foremost, and every holy cow and sheep in the barn he was born in. They believed in the Promised Land. It was far away, the Promised Land, on the other side of the world, but they believed that Jesus meant for them to be here, in Georgia, in the land of cotton, their own Promised Land, hard as times were. Jesus and Mary and Joseph were their people, country people suffering under the sun, and the people of Cotton County would be redeemed. They believed in Redemption, that their losses on battlefields, their losses in cotton fields, would be remembered and repaid in the Kingdom of Heaven. They believed in the Commandments. They believed in work, and rising early, and the crops in the field, and the rain that nourished them, never did they believe in the rain more, now that there wasn’t enough of it. They believed in progress, in automobiles and airplanes, and a few of them in the tractors that sat like jungle beasts in their barns. They believed in Charles Lindbergh. They believed in Ty Cobb. They did not believe in Herbert Hoover, but they prayed for him. They believed in prayer, and praise, and warm meals, in the kindness of strangers. They believed in their neighbors. They believed in Georgia, its clays and creeks, in the heavenly mists that drifted over the fields in the morning. They believed in ghosts—for what was the Almighty but the Holy Ghost?—and they believed in miracles. They believed in an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth. Getting caught not believing was like getting caught with your hand in the collection plate. “Any faithless fool tells you your babies ain’t kin,” Juke said to Elma, “you tell them the only sin the Lord don’t pardon is the sin of nonbelieving.”

So they believed that the babies were twins. Because if they didn’t believe, then they didn’t believe Genus Jackson was one of the daddies. They’d have to believe that the daddy was someone else. They’d have to believe that a mob of white men killed a black man for no reason. And they couldn’t believe that.

Except the black folks. They knew what their white neighbors were capable of. They believed in the same things the white folks believed in, except they didn’t believe in the white folks. (Some of them didn’t believe in Georgia. Some of them believed the only Promised Land lay north.)

Except they didn’t believe in outsiders, either. Neither the white folks nor the black folks believed in outsiders. None of the folks, black or white, knew Genus Jackson. If they had, maybe one of them would have been seen crying on a porch, or writing a letter to Walter White, or taking up a collection for a funeral.

So even Ezra and Long John and Al believed the story that was told. They sat on their stools at Young’s and talked it over. Ezra said, “Boy done come to the wrong town.”

Long John said, “Never did like that hunchback boy.”

Al, who was the oldest, who had sons of his own, said, “He all right. He just a poor child of the Lord. Poor child done fell for the wrong white girl.”

He’d been lucky while he was alive, Ezra said, he’d been treated too good, put up in that shack without paying a penny. Besides, the boss gave them a pint of liquor every harvest, and his daughter, at Christmas, she made them pies.

FOUR

THERE WERE FOURTEEN BOOKS IN THE BIG HOUSE. THE THREE Bibles, including the babies’. The family Bible, marked with the birthdays and deaths of Jessa as well as Ketty, was kept on the mantel, where it collected the yellow light of the fire, and from which Elma read a passage aloud at the table each night. There was a book of fairy tales by the brothers Grimm. A book of poems by Edgar Allan Poe, a gift from Elma’s schoolteacher, Miss Armistead. The Farmers’ Almanac (each January the old edition went out to the privy). And a children’s encyclopedia, in eight illustrated volumes, called The Book of Knowledge, which Juke had bought for Elma’s birthday from the rolling store when it was a good year for cotton. If Nan hid a volume of the encyclopedia inside her corn-shuck mattress, nobody missed it, least of all Juke.

In a house full of secrets, one of the first was between Nan and Elma. The winter Nan was six and Elma was ten, their throats began to ache in the middle of the night. Juke looked in Nan’s mouth and saw her throat was coated with what looked like gray putty. He thought it was a clump of clay she’d eaten. Then he looked in Elma’s mouth and saw hers was the same. The next morning he drove them into town, to Dr. Rawls’s office, and the doctor said it wasn’t dirt but diphtheria. Juke carried Elma into her exam room, then carried them both into the colored room so Elma could talk for Nan. “She’s got the chills.”

“How do you know?” asked the doctor.

Elma shrugged. “She told me.”

They had their own way of talking, even then, their own system of signs. Elma knew how to watch Nan and guess what she meant, like a game of charades. Elma guessed, and Nan nodded. It was that first time when they were quarantined in a shack behind the house that Elma taught her to read. She’d put on a bonnet, because that’s what her schoolteacher Miss Armistead wore, and if Elma couldn’t be a farmer like her daddy, she wanted to be a schoolteacher. Nan would trace the letters in her tablet with a pencil, repeating each one in her head. No one bothered with them there. Nan’s mother, Ketty, who couldn’t read herself, passed them their meals through the window, and when spring came and Juke looked again into their mouths and declared them cured, he burned the shack to the ground, the tablet with it, but the letters stayed in Nan’s head. They were three months in the shack, and three months Elma was out of school.

So while Elma read Juke the morning news, or a letter from his people in Carolina, Nan played as dumb as he was. She had no tongue to prove herself, and in this her silence kept her safe. She hung the wash. She shook the dirt from the peanuts. She cooked and canned and patched the holes in Juke’s overalls where his knees had worn through. She waited for her father to return. She waited and she waited. She looked out at the road and listened for the automobile he would arrive in. In the daylight, it mattered little that she could read and Juke couldn’t, but there were certain nights when it helped to know she could open The Book of Knowledge and go away for a while, get lost in Antarctica, or in Paris, France, or Baltimore, Maryland, the place her father lived, a place that seemed just as magical and just as far as the pyramids. In this way the words on the page paved a gentle road to sleep. She’d nibble on the white clay she kept on a pantry shelf in an old coffee tin her mother had used for the same purpose. Ketty said it was natural, just as chewing cured tobacco leaves was natural—it was God’s own bounty and it made a day go down easier.

It was on those nights, the nights when Juke came for her, that having no tongue was a mixed blessing. If she’d had a tongue, she could have said no. But would a word have stopped him? Was it better to have no tongue if a tongue was no protection?

The first time he took her to the still was the night they buried her mother. It was just for the gin then. Juke said she was ready for a man’s drink. The log cabin was off to the west of the house, beyond the corn, just up the bank from the creek and not fifty feet from the road, but hidden from sight by long-skirted pines and thick-waisted oaks and the Spanish moss that looked to Nan like witch’s hair. She had heard Elma say before that her daddy was out at the still—some nights he even slept there—but she couldn’t imagine what it was for, or what it looked like, only knew that she washed his tumblers and that they weren’t for tea. She had seen the cabin only once, when a trail of blackberry bushes brought her there, like bread crumbs to a gingerbread house.

That night, he sat her down on an old stool made from a pine stump. The cabin was dark, lit only with a candle; Elma was in the big house, asleep. The air was musty, close; it smelled of a sweetness she’d never smelled before. He offered her a sip from his mason jar, and the sweetness filled her nose and her mouth, burning all the way up to her eyes, which filled with tears. The gin dribbled down her chin, as sometimes happened. Juke laughed a not unkind laugh. She did too, and the sound was big in her ears.

The second time, he showed her how the still worked, let her touch the cooking pot, the thumper keg, the condenser that was cool to the touch. He let her play on the barrels. She hopped from one to another like a cat. He watched her while he whittled away on a piece of pine. He carved her a little wooden cat. “You just a curious little cat, ain’t you?”

The third time, he had her sit on the mattress, this one filled with Spanish moss, which he slept on when he had a big batch going. Under the mattress he kept a twelve-gauge shotgun, which he took out and stroked with a square of wash leather in the light of the candle. “Know who gave me this gun?” he said.

Nan shook her head.

“Your daddy.”

She wanted to reach out and touch it, but she didn’t. It was an object she’d seen a thousand times, as plain as his tin of tobacco, but now it shone with a new brightness.

“You remember your daddy?”

Again she shook her head. She did remember him, she thought she did. She sometimes dreamt of the tickle of his mustache and the smell of his corncob pipe. But it was easier to say no.

“Damn shame he left,” he said, shaking his head. “Ain’t no man who can leave a child. I wouldn’t never leave you like that.” He reached under her and slipped the gun back under the mattress. “Even Elma never been out here,” he said. “Even Elma I don’t ’low to have no man’s drink.” And it was true she felt a little special—her momma dead, her daddy gone, and the boss man paying her attention—even as she held her nightdress tight around her hips. The gin pumped warm through her heart.

The fourth time, he told her to lie down, weren’t she tired from that gin and the late hour? He told her to close her eyes. He told her to put out her hand. She did as she was told. In her palm he placed what felt like a marble, and when she opened her eyes she saw that it was a pearl. “It belonged to your momma. Must have lost it while she was cleaning the big house.” He wanted Nan to have it, for luck. It was smooth and white with a bluish sheen, like the skin that formed at the top of a bucket of milk, a tiny hole pierced through either side. Nan held it in her hand until she was back in her own room, and then she hid it too, in her corn-shuck mattress.

The fifth time, he lay down beside her. He stroked her braids, which had gone wiry. Such pretty hair, he said, but weren’t she lonesome, no momma to tend them?

And like that.

When her body had become a woman’s, he told her it was word from the Lord that she was ready to know a man, like the Bible called for. But it meant he had to pull away and do his business on her chest or belly or on the wool blanket, which she washed in the laundry come Tuesday. “I’m too old and you too young to raise no youngun,” he said, almost merry.

She never fell asleep there in the cabin, always waited for him to get up and go outside to make water, then went ahead of him back to the house, where she could sleep on the other side of the wall from Elma. Later, on her own mattress in the little room off the kitchen, she tried to settle her eyes on a book, the gin cooling in her veins. She supposed she could have run from him. She could smash a jar and cut him with it. She could take his shotgun from under the mattress and shoot him with it. In her room, when he came for her, she could make a ruckus, waking Elma. On nights he was rough and quick, when he had no kind words for her, or no words at all, she wrote a letter to Elma in her head. Telling.

But what could Elma have done, even with a tongue? What power did she have to stop her father?

It would be worse, Nan decided, if Elma knew. Worse than the shame of being under him was the shame of being under him inside Elma’s head.

She wouldn’t wait for her father to return any longer. She would go to Baltimore and she would find him. She would look up his name in the phone book. Sterling Smith.

Some nights, when Juke came to her room, it was to tell her that she was wanted to deliver a baby. Then her heart pounded with relief. Suddenly she was awake. She hurried to dress and take her mother’s satchel—her birthing bag, she’d called it—and go outside, where another man’s truck or wagon sat in the driveway. Usually it was a wagon, and the driver was colored, and the wagon was headed for the Youngs’ farm or the Fourth Ward or Rocky Bottom, the ragged country beyond the Fourth Ward where Negro croppers tried to make the ground yield. Juke watched from the porch as she rode away, and though she had a long, uncertain night ahead of her, for a few hours she could escape.

“You ain’t no granny woman,” one father told her, sizing her up. “You ain’t no more than a granddaughter.” Most mothers she didn’t meet before the labor, and by the time a father discovered how young she was, it was too late to find someone else. But before long her silence relaxed them, loosened their mouths. Nobody talked as much as a man driving home to his wife in labor in the middle of the night. They talked about cotton and corn, about their families waiting, whether the mother had had an easy pregnancy or a hard one. One man recounted an entire baseball game between the Chattanooga Black Lookouts and the Atlanta Black Crackers, a game narrated to him by his cousin, who had been there.

A mother in labor, though, didn’t like to be talked to. There wasn’t much Nan needed to say that she couldn’t say with her hands. A wave to tell her to push, a different wave to tell her to stop pushing. A hand on the forehead, or a hand in hers, for comfort. Quick, steady hands. “You look just like Ketty,” the mother might say, and the words gave Nan courage. Each time the baby came, Nan loved it. She bathed it and bundled it and held it as long as the mother would allow. The next morning, after the sun had risen, after Nan had been made a cup of coffee, after the brothers and sisters had tumbled naked out of their bed to see the baby, after the afterbirth had been planted in the field to ensure a good crop the next year, the father would drive her home. On the way back, he talked less. His nerves had calmed. He was tired. Maybe he was thinking about next year’s crop, whether there would be enough to feed the new child. They were poor folks, every one of them, log walls lined with newspaper and pasteboard boxes, no clean towels but fertilizer sacks. Sometimes they paid Nan in hen eggs or gourds, once with braided brown bread the mother had made herself, in the early waves of labor, once with a handful of caramel milk-roll candies, seeing how young she was. Once she tasted them, Nan might have liked to be paid in caramel milk rolls every time. (Some folks thought she couldn’t taste at all, but she could taste fine; she could taste with the stub of her tongue what it took another person a whole tongue to taste.) Ketty’d had a tongue for bartering, but even with a tongue Nan might have only accepted what was offered. What right had she to what little a family had? One mother of six offered Nan the baby itself, and Nan had stood there and rocked that baby, a girl, and imagined taking her home, a baby that looked to her like family, better than any doll baby, and then handed the child back to the mother, hoping she would never know how pitiful her parents’ love was.

But there was a kind of peace in those Rocky Bottom cabins, miles from any crossroads store. A body could farm what little land he had a right to, or have as many children as she liked, and be left alone with their seeds and their rags. So many children they were giving them away, so what was one more mouth to feed? It would be easy enough for her to stay. They were her people out in those cabins. She could earn her keep. She’d saved half her earnings from her deliveries, which she squirreled away in the inside pocket of her satchel. If she got two coins, she put one in the satchel and gave Juke the other. If she got four, she gave him two. It wouldn’t be long before she had enough to put together and make something with. Before her mother had died, she’d told her, “You stronger than folks think. You got a strong mind and strong hands. You be ready to go out into the world soon enough.”

But then there was Elma. She was her people too. If she told Elma, maybe Elma would come along with her. The idea made Nan dizzy with hope. Leaving would be easier, less lonely, with Elma. It would be safer. Even grown men, whole families, the ones who were streaming north on the trains to Washington, D.C., to Philadelphia and Harlem, had to leave under cover of night. She heard about them on her calls, folks who were pulling up their roots and planting themselves in the snowy cities where you could walk down the sidewalk without having to step off when a white person came along. You had to be careful. If you were a sharecropper, you had to find a way to get out of town before word got out, or the planter would find a way to make you stay. George Wilson might send his grandson out for you, or the sheriff. Even her father had had to ride a freight train, the story went, when he left for the North.

There was one family that lived in a shotgun shack in the Fourth Ward, just over the tracks. The mother was expecting her third child. Ketty had delivered the first two, and Nan expected to be called for the next, but they never called. After enough months had passed, Nan concluded that the mother had lost the baby, but later she learned from the family next door that they had up and left for a place called Scranton, Pennsylvania, where the mother had people, and the neighbors had been as surprised as Nan. The father, a diabetic who had worked in the picker room at the mill, had complained to Freddie Wilson, the foreman, that his feet grew numb when he was on them for too long, and Freddie had told him that he should be grateful for the work and do it without complaint, and that if he didn’t want to stand he could kneel on the floor and clean it, every square foot of the mill. So the man had waxed the floors, scrubbing on his hands and knees where the white women stood spinning, and though he kept his eyes on the floor, Freddie would say, laughing at himself, “You looking up that girl’s dress?” and whack him with the straw end of his broom. When he was done cleaning the floor, Freddie made him lick it. “Taste clean?” And then, because twelve hours had passed and his next shift was coming on, Freddie sent him back to the picker room. And not long after, before anyone knew to say good-bye, the man had taken his family out of Florence. He sent a letter to the neighbor saying he was working in a printing factory, where the hours were just as long but where at least he could operate his machine sitting down. The neighbor told Nan that the third child was born in a hospital, and they named him Zane.