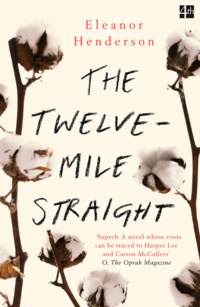

The Twelve-Mile Straight

Afterward, he cried. “Don’t do me like that again, honey,” he said. “Don’t make me do that again.” There was no uglier sight in the world, Nan thought, than a naked white man crying.

FIVE

BEFORE SHE GOT IN THE FAMILY WAY, ELMA HAD BEEN SET ON going to the teacher’s college in Statesboro. It was where two girls from her class said they were going. Elma had the grades. She just didn’t have the money. The fall of her last year in school, she tried to get work at the Piggly Wiggly, at the theater, at the crossroads store. She even put up a notice on the bulletin board at church: ELMA JESUP. MOTHER’S HELPER AND HOUSEGIRL. CLEANING. COOKING. SEWING. Nobody hired her. Every week she checked the board to be sure the note was still there. Then one Sunday, on that same bulletin board, another notice caught her eye: the Florence chapter of the Georgia Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was offering a college scholarship to “a young lady of good character.”

Elma liked school. She just didn’t like the people there. Boys had always liked her because they liked her daddy’s liquor. They thought they might come out to the farm and get into his stash and get under her dress. They called her Red. Clever! They said, “You wanna go have a pull from my bottle, Red?” They pawed her braids. “You watch them town boys,” her father told her. Freddie was the only one he didn’t mind. The girls weren’t particular about her because the boys were, and because they thought she was white trash and a drunk, and because already they were following their mothers to the WCTU meetings at the Hotel Chanticleer. In fact Elma had never had a drink—“Ain’t for womenfolk,” her daddy said—and that was fine by her, she didn’t like the way it smelled on a man’s breath and made a man loose and rough and mean.

There was no reason, she thought, she shouldn’t have that scholarship. She’d get out of Florence and become a schoolteacher, and if it meant joining the WCTU, she’d do it. She told her father the dollar was for her graduation cap and gown, and though he grumbled about it, and had to collect it in coins, he gave it to her. She asked Josie Byrd if she could go with her to a meeting after school, and Josie Byrd said certainly, it would be grand, and loaned her a felt hat that looked like a bathing cap. Only later did Elma discover that for every new member you brought in, your name was entered in a raffle for a year’s supply of Octagon toilet soap.

The women at the Hotel Chanticleer all wore rhinestone broaches and white ribbons and strands of evening pearls down to their navels. They poured Elma tea and piled her plate with shortbread cookies and said, “How do you do?” She knew Tabitha Quick and Carlotta Rawls and of course she knew Parthenia Wilson, she had opened her legs to Parthenia Wilson’s grandson in the bed of his truck the day before, but by the time she was shaking Mary Minrath’s hand, she understood they were pretending they didn’t know her, that they were forgetting that she was Juke Jesup’s daughter. They were meeting her for the first time. And maybe they were! Maybe she would be reborn, fatherless, in the WCTU! Elma understood this was because they wanted her dollar, and they wanted her to sign, at the end of the meeting, their abstinence pledge. And yet she let them court her. She let them compliment the felt hat that wasn’t hers. She told them what soap she washed her hair with and let them stroke it. She answered questions about her favorite subject in school, her favorite church hymn, her favorite meal to make for supper. Is this what they did in women’s clubs? Eventually they began to speak in a code. They referred to each other as “Comrade” and “Sister”; they spoke with reverence of their “Foremothers”; they spoke with disappointment of “unfortunate girls.” They spoke about Hoover (well, the white-ribboners believed in Hoover) and about “rum and ruin” and “the flag of booze.” They spoke with growing concern about how they might bring Christ to the country, to the Negroes and halvers, the heathens and drunkards. Tabitha Quick said Georgia was in such a state of debauchery that if God didn’t intervene, “Black heels will be on white necks.”

Elma didn’t understand. She thought of black necks. But this was before the lynchings had started up again. “White necks?” she whispered to Josie.

Josie tried to shush her. Elma did not seem to be the only woman ruffled by the phrase. Josie whispered back, “They mean the Negroes will take over town. The ones at the saloon.”

“Young’s, I believe it’s called,” said Tabitha Quick.

“Not the Robert Youngs,” someone clarified.

“They belong in the county camp,” said another.

“Let’s not pretend it’s just the blacks. White heels on white necks too.”

“Perhaps one white heel in particular,” said Mary Minrath under her breath.

“Perhaps one redneck in particular,” said another woman, more loudly.

“Might as well be a black heel,” said Mary Minrath.

“Enough,” Tabitha Quick said, standing up to pour more tea.

“She could be useful,” said Mary Minrath, and only then did Elma understand they were talking about her, and about her father.

Parthenia Wilson was quiet. She fanned herself with her newspaper. It was her silence that infuriated Elma. Elma shat in the same privy Parthenia Wilson had once shat in. She didn’t want to be reinvented by her; she wanted, even then, to be recognized.

Someone said, “We don’t mean to make you feel unwelcome, honey.”

Another said, “We couldn’t be more pleased to have you.”

Elma put down her tea. She didn’t know what to say. Was she to defend her father? What was it they hated about him? Was it just that he was a bootlegger? Or that he was friendly with Negroes?

She thought of the way her father protected the still. She was not to visit it. She did not care to visit it, she had no fascination with it, only a fear of it and a fear that it would be taken away. Her fear was her father’s, that the still might be destroyed and him with it. Sometimes when a car came for Nan in the middle of the night and he was one kind of drunk, he’d come running from the cabin with his shotgun, mumbling about “guvment men.” For all her shame about her father’s work, she knew that, without it, they’d be as poor as any of the croppers on the Straight, as poor even as the Negroes in Rocky Bottom.

She didn’t want to betray her father. But she wanted that scholarship.

She looked around the hotel lobby, the circle of women with their tea saucers in their laps, all of them waiting for her to speak. They were not looking at her like she was a young lady of good character. They were looking at her like she was an unfortunate girl. The scholarship, she knew, was not hers. She did not know that it had already been promised to Josie Byrd.

Parthenia Wilson had said nothing, but she was the target Elma settled on. “Takes more than one white neck to bootleg,” Elma said. “Takes a rich white neck, from what I hear.”

Parthenia Wilson paused her fanning for a moment.

Elma looked at her and said, “Your grandson don’t care what color neck I got. He just cares about necking.”

Parthenia Wilson opened the newspaper she was holding and appeared to begin to read it. She did not remove the newspaper from in front of her face for the rest of the meeting.

Elma might have been excused if it had not been considered impolite. Besides, they wanted her dollar. She didn’t give it to them. She didn’t sign the abstinence pledge. They spent the rest of the meeting organizing a meal train for Bette Hazleton, who was suffering from pleurisy.

After the meeting, Josie Byrd’s mother carried her back to the farm in their Ford. She saw Mrs. Byrd scanning the farm for the cabin, her eyes moving right past the stand of pines along the road. Juke asked her where she’d been, and she told him. She couldn’t lie. She gave him back his coins. “It’s low, Daddy,” she said. “Folks look on us like we’re low.” She waited for the whip of his temper, but he was the right kind of drunk—merry—and he said, “That still is the reason you ain’t eating hog hearts.”

So Elma did not become a schoolteacher. She did not go to the teacher’s college in Statesboro because she didn’t have the money and because already, sitting in the lobby of the Hotel Chanticleer, she was pregnant. Her father pulled her out of school that winter. Soon her belly would start to grow. Her father kept her home from town, from church, made sure she couldn’t be seen from the road. Folks in town went up in arms about a baby born without a ring on the momma’s finger. Didn’t matter if the ring was made of corn silk, long as it was a ring. It had happened to a girl at the mill last year and the other spinners had made sure George Wilson found out. He sent her back to Marietta with her baby on the train she’d come in on. Elma thought that girl was lucky, to be sent away from all those judging eyes. She had come back six months later with a baby and a husband. No telling if the husband was the father of the baby, but that hardly mattered.

Freddie had said he was saving for a ring, but Freddie had all the money he needed. He stopped coming around the farm so much, and then he stopped coming around at all. Before she stopped going to church, before she was stuck on the farm, folks told Elma he was laying out all night in the mill village, where he was sometimes seen on a porch with this girl or in his truck with that one, having a big time. She wondered if it was what she’d said to Parthenia Wilson in the Hotel Chanticleer, or if Freddie would have dropped her anyway, if his grandmother’s disapproval was a handy excuse. She couldn’t let it go; she wrote him a letter. Is it your grandmother who don’t want you tied down? she asked. And if she don’t want you tied down, is it tied down at all, or tied down to me? She didn’t expect a response, was disappointed but not surprised when day after day the postman brought none. He had probably never gotten the letter, she told herself. His grandmother had surely intercepted it.

When her father was yet another kind of drunk—very drunk, tired, weepy—he’d tell Elma her mother would be proud she’d gotten so far in school, even if she didn’t finish. Elma’s mother, Jessa, hadn’t gotten past the fifth grade before she came to town to work in the mill, and Juke hadn’t gone at all, had been sent into the field at six years old with a ham biscuit, a bull-tongue plow, and a john mule named Lefty. After the babies came, he told Elma that her mother would be proud she was such a good momma herself, and though Elma mostly wore a serious face, like a white stone mask, some color rose high in her cheeks then. Jessa had lost her chance to be a mother, and when Juke watched Elma soothe a crying baby on her shoulder, he looked as pleased and loving and haunted as if he were watching his dead wife herself. And though the baby would be calm by then, he would cross the room and take it in his own arms, rocking it, humming a song only it could hear, saying, “Come on and give Granddaddy some sugar,” saying, “Come on and hug my neck.” Sometimes he came in from the field and went straight for Wilson’s crib, lifting him up to study his face.

At times, Elma missed the notion of a husband. When she was lying awake at night, nursing a baby, she thought it would be nice if there were a grown body sleeping next to her, if she could reach over and touch a man’s bare back. But it wasn’t Freddie she wanted there. Just because her pride was hurt didn’t mean she was sad he was gone. Sometimes it was Genus’s long, slim back she imagined, when she couldn’t keep the picture from her mind, but then she saw him disappear into the woods in his union suit, the same suit he was hanged in, and then her mind reared up and trotted away like a horse with a snake on its heels.

One morning in that blazing and interminable month of August, when Elma arrived with her wagon at the crossroads store, a man she didn’t recognize offered to help her carry the eggs inside. No one else was about—not Jeb Simmons nor his son Drink, no one playing checkers on the porch. Or had she seen the man before? The sun was in her eyes. She could manage fine, thank you, but he wouldn’t hear of it. She held the door open for him while he carried in the crate, placing it on the shop counter, behind which Mud Turner eyed her, cigarette hanging from his mouth.

Overhead, a ceiling fan spun. Elma stood with the man just inside the door. “Must be nice to step off the farm,” he said to her, and that was when she placed him—the sharp-edged suit, the neat mustache. He took off his hat and introduced himself: Q. L. Boothby, the editor of the Testament. He’d driven down from Macon that morning. Wasn’t it a fine morning? But already so hot. “A good morning for a Coca-Cola, Miss Jesup. What do you say?”

Behind the counter, Mud raised an eyebrow. The last time Elma had had a soda was with Freddie, at Pearsall’s drugstore in Florence. Winter, before she was showing, before he’d stopped calling on her. They’d just seen Anna Christie at the theater next door, Elma’s first talkie, and her heart was still pounding with the thrill. Ordering her soda, she tried to imitate Greta Garbo’s voice—“Gimme a vhiskey, ginger ale on the side. And don’t be stingy, baby.” Freddie laughed. Excepting the colored one, there were no saloons to order a drink from in Florence, just the cotton mill, where it was mostly the men who drank from mason jars on their porches. Elma’s father wouldn’t let her set foot in the mill village, but here she was, out on the town with her fiancé, Freddie Wilson, whose family owned the biggest business in town, the whole glittering evening, her whole life, before her, and who cared how Freddie got his money, it was the way her father got his money too, and it was buying her a movie and a soda. The bubbles fizzed in her belly. Or was that her baby, kicking already?

Elma tasted that ginger ale now, cool and sweet, the tinkle of the ice cubes as she stirred them with her straw. She looked at Q. L. Boothby, his hat still in his hands. He was as finely dressed a man as she had seen, his black Oxfords shiny as a piano, a blood red handkerchief flaming from his breast pocket.

She said, “Sir, you don’t scare off easy, do you?”

He said, “I won’t take much of your time.”

From Mud he bought two bottles of Coca-Cola and carried them to the checkers table on the porch. Elma might have learned her lesson about daydreaming, but for a moment she imagined that they were on a date. That they were somewhere else and she was someone else and the man across from her was her fiancé. She thought a fiancé might be better than a husband. The promise of a mate, without the burden of one. The beginning without the end.

“How are the babies?” Mr. Boothby asked.

Elma twisted the cap off her Coke and watched its breath escape from the bottle. She’d had no more sleep than a mule the night before. Winna Jean had been up crying half the night, and she’d only sleep at Elma’s breast, with Elma propped straight up in bed. And Wilson had a case of the runs so bad that Nan had to cut more diapers out of an old sack apron and double them up, and slather lard on his poor red behind. It was best that Elma should be so tired, that she should sleepwalk through those nights. Then there wasn’t enough sleep between them to worry about which baby which of them cared for, or whether Elma should feel grateful or guilty or bitter that there were two of them to care for the babies, and two babies instead of one. Elma said, “The babies are fine.”

“Appears to me you must be plumb tired of all the attention those babies bring. Sweet as they are.”

Elma took a cautious sip of her soda. Yes, it did taste just as sweet as Heaven. He was warming her up, breaking her down, but it did feel good to sit on a porch and talk to a stranger. “I only want to keep them safe. All types of people coming in, it agg’avates em.”

Mr. Boothby held up his hands, as if to show they were empty. “I understand, I understand. I’ve got children of my own.”

Here Elma’s fantasy paled a little. Now she pictured Mrs. Boothby. Did she have an electric kitchen up in Macon, with a Frigidaire and an electric stove?

“I have no interest in your babies, Miss Jesup, miraculous or not. I’m a newspaperman. We call our publication the Testament, and we do pride ourselves on seeking the truth.” Mr. Boothby lowered his voice when he said, “It’s the Negro Mr. Jackson I have an interest in.”

Elma folded her hands in her lap to hide their shaking. Bill Cousins passed by on his way into the store, tipping his hat and saying, “Morning,” his eyes taking them in. Elma felt her heart speed up. No one, of course, would believe Mr. Boothby was a friendly acquaintance, let alone a suitor, but if Bill Cousins recognized the man in the suit, he didn’t say so. If he did, he might incite a mob against Elma herself. She might be burned at the stake for talking to a big-city reporter, even if they didn’t know his politics. There were things no one wanted known by the outside, and no one knew that better than Elma. When the door had closed behind Bill, she said, “Well, I’m sorry to tell you, Mr. Boothby, but the Negro Mr. Jackson died a few weeks back. Figure you would have read about it in that paper of yours.”

Mr. Boothby smiled. “You don’t say. How did he die?”

“I didn’t see it myself.”

“How did your father say he died?”

Elma paused. “He was swung up.”

“So your father was there.”

“Didn’t have to be there. There was a picture in your paper with the rope hanging from the gourd tree. It’s all accounted for.”

“And who is responsible for hanging the man? What do the accounts say?”

“Sir, don’t you have a Roosevelt to cover?”

Mr. Boothby cocked his head. “Pardon?”

“Your friend up in Warm Springs. The one you’re building the polio hospital with. Sounds awful important. It’s about alls your paper is like to talk about.”

Mr. Boothby laughed. “Well, you do keep up with the Testament, don’t you? I’m mighty pleased.”

Elma sipped her soda, then guzzled it. She could feel her defense dissolving, and she allowed herself not to care. Talking about it was better than not talking about it—it was the not talking about it, the silence her father had enforced, that was so heavy. “Freddie Wilson swung him up. He even traded shoes with him. But he ain’t my fiancé no more. I don’t know where he is, and I don’t care to know. He ain’t worth a milk bucket under a bull.”

Mr. Boothby smiled. He withdrew a pipe from a pocket inside his jacket and lit it. He had no notebook, no pen. “That’s what the autopsy confirmed. I know the man who performed it. I can attest to its accuracy. It would be one thing if the man were shot dead first, then hanged without protest. What I can’t seem to understand, but which everyone else in the state of Georgia seems to understand just fine, is how one man managed to hang another live man all by himself.”

Elma was beginning to sweat. Even in the shade of the porch, the morning heat crept into her collar, under the braid pinned to the nape of her neck. Her mind stuck on the phrase from the paper, “Cervical spine.” She said, “Freddie, he had a gun. A rifle. Maybe he trained it on him.” She shrugged. “Like I say, I didn’t see it.”

“Appears to me, it’s hard to hang a man while holding a rifle to his head. If it were me, I’d put up a fight. Give him a kick with my alligator boots. What’s more likely is there were others who helped Freddie. Maybe many others.”

If Elma stepped down from the porch and looked over her right shoulder, she could see her father’s cotton coming up. No flowers yet—just green. She could stand up and walk home. If she called out, her father might even hear her voice.

“What I’m saying,” Mr. Boothby went on, “is that your fiancé may be taking the fall for his associates.”

“Associates? All Freddie associated with were drunks.”

“He worked for your father, Freddie did.”

“He was foreman at the mill. Freddie said farmwork was for coloreds. He was coming up under his grandfather.” That was all Freddie talked about, taking over the mill when his grandfather retired. This is all fixing to be ours, he’d say, parked on the hill overlooking the mill village.

“I’m not talking about farmwork,” said Mr. Boothby. “Or millwork, for that matter.”

Elma blinked out at the road. She wondered if Mr. Boothby had ever had a drink in his life, and if such a man was worthy of pity or admiration. A pickup passed, a green Chevy like Freddie’s, and for a moment she held her breath. Then she saw it had Alabama plates. “I don’t know about Macon,” she said, “but in Cotton County, that’s about the only kind of work we do.”

“Oh, I know about your industries here. What do you know about George Wilson? He owns the cotton and the cotton mill, does he? And the mill isn’t all he runs, what I hear. How’s he find time for it all, is what I wonder.”

“He’s got brothers up near Atlanta who help with the business. And Freddie helps him. Helped him.”

“With what part?”

“I wouldn’t know. I don’t spend much time at the mill. The village is full of riffraff.”

“Was Freddie part of the riffraff?”

Elma snorted a soda bubble. “Yes, sir.”

“How so?”

“He liked to carry on. Tear his truck around the village. Get into fistfights. Once he got shinnied up and shot the headlights out of his own grandfather’s Ford, and blamed it on some poor fool. Went and got him fired quick as you can say Wilson. He was the king of riffraff. He liked to call himself King Cotton, fancied himself royalty, fixing to take on the family business. But he couldn’t even take on a wife and child.”

“Why not?”

“Don’t ask me! Ask him! He had nine months to put his pants on, same as any daddy. His family’s got enough houses to put us in, that’s for sure. All we’d need was one.” Six months along, her father had carried her over to the Wilsons’ house, where Freddie had been raised up by his grandparents in his father’s old bedroom. Elma’s father had made her wait on the porch in front of the parlor window, her full figure framed like a picture. She saw Mr. Wilson, then his wife, heard Freddie’s voice deep within the house, and then the curtain was drawn and a colored girl brought her a lemonade, sour and full of seeds. After five minutes her father came through the door, jammed his cap on his head, and got in the truck. He didn’t say a word. By the time they turned onto the road, Elma knew that Freddie would not be marrying her. Her baby would not have a Christmas stocking on the Wilsons’ mantel.

She had given up on a reply from Freddie, but there it was in the mailbox a few days later, her name in his loopy, second-grade cursive: Dear Elma. It was both, he admitted: his grandmother didn’t want him tied down, and didn’t want him tied down to her. She don’t care for country people, was the way he put it, and she was almost grateful for his gentleness. He apologized not for dropping her but that her father had been sent away from the house. I did want to marry you, he wrote. That was all, and at least there was that.

“Least my own father took up for the babies,” she told Mr. Boothby. “Gave them a roof. I’d rather be in his house than any of those linthead shacks at the mill.” Of course her father’s house too was owned by the Wilsons, the house and the fields and the food they put in their bellies. They owned their shit and the outhouse they shit in. And a Wilson did not marry his property. He would just as soon marry a Negro in a cabin. That afternoon when her father had driven her to their house, the Wilsons didn’t yet know Winnafred, didn’t yet know that she was said to tumble around with a Negro for the nine dark months inside Elma’s belly. But even before she was born, they had disowned her.