Mr Atkinson’s Rum Contract

Grenville reckoned that if this duty were cut, making it cheaper to import French molasses legally than to pay the bribes and run the risks that attended smuggling, it would have the counter-intuitive effect of raising revenue; and so parliament voted to halve the tax on foreign molasses, to three pence per gallon, from April 1764. The Sugar Act sparked outrage in America. ‘There is not a man on the continent of America,’ fumed Nathaniel Weare, the comptroller of customs in Massachusetts, ‘who does not consider the Sugar Act, as far as it concerns molasses, as a sacrifice made of the northern Colonies, to the superior interest in Parliament of the West Indies.’[23] A writer in Rhode Island’s Providence Gazette ranted that American interests had been trampled by a ‘few dirty specks, the sugar islands’.[24] Their common hatred of the Sugar Act united the New England colonies for perhaps the first time, and set them on a collision course with the mother country.

BRITANNIA RULED the waves, for the time being, and her navy patrolled the waters of the North Atlantic and Caribbean, watching for French and Spanish attempts to violate her citizens’ interests. To give one trivial example, tensions had long festered over British loggers’ claims to the timber in the Spanish-held territory of Honduras. It is amid such rumblings that Richard Atkinson makes a fleeting appearance, in the earliest letter that I have found in his hand, dated 29 June 1764. He writes to the Secretary to the Treasury, Charles Jenkinson, with information from the merchant grapevine: ‘As any Intelligence concerning the Bay of Honduras will I presume be acceptable I take the Liberty to send you an Extract of a Letter from the Same Hand as the former …’[25] The letter may not make for stirring reading, but it proves that Richard was already cultivating contacts at the very highest political level.

Meanwhile, George Grenville announced a new tax on the American and West Indian colonies. A stamp duty – such as had existed in the mother country since 1694 – would be payable on a range of paper items, from almanacs, newspapers and playing cards to conveyances, diplomas, leases, licences and wills. Each colony would appoint its own stamp distributor, who would take a small cut of the proceeds, but otherwise the tax would be largely self-regulating, since without its stamp any official document would be null and void. The bill passed through the House of Commons ‘almost without debate’. Only Colonel Isaac Barré, a fearless orator whose left eye had been shot out during the capture of Quebec five years earlier, punctured the chamber’s complacency with a ‘vehement harangue’ in which he argued that the very reason the colonists had emigrated to America was to flee such measures.[26] The king gave his assent to the Stamp Act on 22 March 1765. No one could have predicted its consequences.

Resistance erupted in Boston on 14 August, when the newly appointed stamp distributor for Massachusetts was hanged in effigy from the ‘Liberty Tree’. It was unsurprising that the Bostonians should be foremost among the ‘Sons of Liberty’ – who took their name from a phrase used by Colonel Barré – since theirs was a literate and litigious mercantile community upon which the duty would weigh heavily.

By the time the Stamp Act came into force on 1 November, it was clear that the Americans’ refusal to accept the duty would have a disastrous effect on trade, since without legally stamped port clearance papers their merchant ships might be seized at any time. Relations between the American and West Indian merchant communities were already frayed; now the mainland contingent resolved to cut off trade with all those sugar islands that submitted to the Stamp Act. The Jamaicans were the most acquiescent of all – they paid more stamp duty than all the other colonies put together. One Canadian newspaper, reporting an outbreak of yellow fever in Jamaica towards the end of 1765, quipped that ‘the Inhabitants of the Town of Kingston fed so voraciously on the stamps, that not less than 300 of them alone died in the Month of November’.[27]

Although the Jamaicans certainly disliked the Stamp Act, pragmatism deterred them from rejecting it. Whereas the mainland assemblies resented being asked to pay for their own defence, the Jamaican Assembly actively volunteered a financial contribution, at the same time lobbying for an enhanced military presence on their island. The British sugar islands were surrounded by French and Spanish territories, and common sense dictated that these old enemies would soon seek to avenge their humiliation in the Seven Years’ War. Most of all, however, the planters feared attacks from within. As the ratio of blacks to whites increased on the islands – in Jamaica it was roughly ten to one – so did the danger of slave insurrections. In November 1765, as the Stamp Act started to bite, an uprising broke out in the parish of St Mary, on the north side of the island; although it was soon quashed, it must have concentrated the colonists’ minds.

Six prime ministers would hold office during the 1760s. The Marquess of Rockingham, replacing Grenville, adopted a more conciliatory tone towards the Americans – but it would be William Pitt’s denunciation of the Stamp Act which finally persuaded Rockingham that repeal was the only way out of the crisis. Over three weeks, from 28 January 1766, a committee of the whole House considered the proposed repeal bill, with a succession of merchants coming forward to describe the negative impact of the Stamp Act on both sides of the Atlantic. The star witness was the ‘celebrated electric philosopher’ Benjamin Franklin, as the minutes describe him – his experiments concerning the nature of lightning had made him one of the scientific establishment’s most venerated figures. Before 1763, Franklin testified, there had always been ‘affection’ among Americans for the mother country; but recently he had begun to be ‘Doubtfull of their Temper’.[28]

Early on the morning of 21 February, MPs started bagging seats in the House of Commons in anticipation of the afternoon’s debate. Pitt warned that parliament’s failure to repeal the Stamp Act would lead to civil war, and cause the king ‘to dip the royal ermine in the blood of his British subjects in America’.[29] For the time being, His Majesty’s robes remained snowy-white; for both houses passed the repeal bill, along with a face-saving ‘declaratory bill’ that asserted parliament’s right in principle to tax the colonies, and the king gave his assent on 18 March. American and West Indian merchant ships moored on the River Thames marked the news by hoisting their colours and blasting off their guns.

THE AMERICANS HAD MANAGED to overturn one piece of hated legislation; now they took aim at the Sugar Act. On 10 March 1766, at a gathering of colonial merchants held at the King’s Arms Tavern in Westminster, the West Indian contingent agreed that the three pence duty that Americans paid on foreign-produced molasses could drop to a single penny. This was a massive climbdown on the West Indians’ part; and yet, to their great dismay, when the American Duties Act passed into law in June 1766, it imposed a penny per gallon duty on all molasses imported into the mainland colonies, thus eliminating any advantage possessed by the British sugar islands over the French. These reforms were too technical to be of much public interest, but they marked a further cooling in relations between the colonial merchant lobbies. By now the West Indians wholly distrusted the Americans, believing them to be motivated by treacherous ambitions to trade freely with the French.

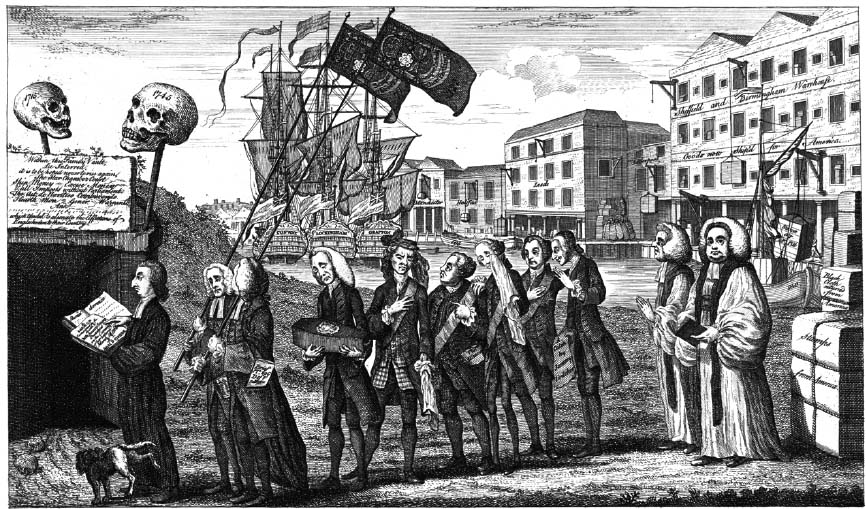

At its ‘funeral’, the Stamp Act is taken in a tiny coffin to a burial vault reserved for especially detested laws.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division

Until the 1760s, the West Indian interest in the City of London had been informally managed. The Society of West India Merchants emerged as a lobbying organization sometime during this decade; its precise origins are obscure, since the minutes taken at its meetings before 1769 no longer exist. Under its chairman, Beeston Long, the society usually met on the first Tuesday of the month at the London Tavern, a dining establishment on Bishopsgate Street; attendance ranged from three (a quorum) to many more when feelings about some issue were running high. As the merchants tucked into turtle flesh – these gentle beasts lived in the cellars, in tanks painted with tropical scenes to make them feel at home – they chewed over the concerns of their trade. According to parliamentary records, Richard Atkinson was among a delegation from the society summoned by Alderman William Beckford to the House of Commons in May 1766 in a last-ditch attempt to steer the arguments around the American Duties Act in the West Indians’ favour.[30] The society’s records show that during the 1770s Richard attended around six meetings every year; unfortunately the minutes are so cursory, and so devoid of descriptive colour, that it is impossible to gain much sense of his contribution.

The association between a merchant house such as Mure, Son & Atkinson, and the West Indian planters it served, rested on mutual confidence – not least because an exchange of letters between London and Jamaica often took four months or more. The merchant conveyed a planter’s sugar crop back to England and brokered its sale, taking a 2½ per cent cut of the proceeds. It also sourced and shipped out any tools, provisions and other items required for the smooth operation of the planter’s estates, subject to a mark-up; it recruited his overseers and book-keepers, and arranged their outward passage; it acted as his banker, paying bills of exchange drawn on his account, and advancing credit whenever necessary; it even oversaw the education of his children and ran his shopping errands. In short, it took care of his every need in the mother country.

But it was not quite a relationship of equals. So long as his account remained in credit, the planter maintained a degree of control; as soon as his expenses exceeded his remittances, however, the merchant gained the upper hand. The sheer precariousness of the sugar business – where hurricane, drought or rebellion could wipe out the year’s produce at a stroke – drove many proprietors deep into debt, as what started out as modest loans ballooned into unsustainable mortgages secured against their property. The merchant could foreclose whenever he chose, and many men, including Hutchison Mure, were guilty of seizing clients’ estates by this means.

John Tharp, who owned a number of estates in north-west Jamaica, retained Mure, Son & Atkinson as his London agents from 1765 to 1772. A cache of the firm’s letters sent to Tharp’s plantation house in St James Parish has survived, heavily watermarked and discoloured from years of storage in the tropics. Most of the correspondence is in Richard’s handwriting, and it is illuminating about the seasonal rhythm of the West India trade and the volatility of the sugar market. The cane crop was cut and processed during the early months of the year. Gradually, over the summer, merchant ships returning from the West Indies appeared in the Thames, weighed down with their sticky cargo; if too many ships came at once, the glut drove down the price of sugar, while a scarcity early or late in the season pushed it upwards. The letters stamped on the large hogshead barrels in which the sugar was transported identified the estate on which it had been produced; its quality could be highly variable. ‘Those of the Mark PP were much better than those of the same Mark last Year,’ Richard wrote to Tharp on 13 July 1767, ‘for these were only very brown, those of last Year were black.’[31] (‘PP’ signified Pantre Pant, a plantation that was managed by Tharp in the parish of Trelawny.)

Each autumn, Mure, Son & Atkinson sourced John Tharp’s plantation ‘necessaries’ and other domestic goods, which were shipped out to Jamaica once the hurricane season had safely passed. In December 1767, in time for Christmas, the enslaved population of Tharp’s estates were lucky enough to receive 1,107 yards of coarse Osnaburg linen and the needles with which to stitch the cloth into garments; meanwhile, for the master and his wife, there were tailored frock coats with gold buttons and braid, kid mittens, a ‘very Neat Demi peak Sadle with red morrocco Skirts and doe Skin Seat neatly stitched stirups Leathers & Girths’, a pair of brass pistols, a ‘Copper Tea Kitchin with 2 heaters’, twelve canisters of hyson tea, a ‘Gadroon’d Cruit frame’, a case of pickles containing ‘Capers Girkins Olives Mangoes Mustard Oil Soy Wallnutt French beans Colly flower Anchovies’, a hogshead of claret, casks of lavender and rose water, a selection of wallpapers, fine grey hair powder, guitar strings and the score of the Beggar’s Opera.[32]

NO CENSUS EXISTS to permit more than a guess at how many black people were living in London at this time. ‘The practice of importing Negroe servants into these kingdoms is said to be already a grievance that requires a remedy,’ reported the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1764, ‘and yet it is every day encouraged, insomuch that the number in this metropolis only, is supposed to be near 20,000.’[33] This figure seems likely to have been an overestimate, but not wildly so. Among the wealthy, black servants had cachet, while black children were often treated as toys, to be returned to the colonies once they grew up or their owners tired of them. Samuel Johnson – who was more enlightened about these matters than most – famously employed a black manservant, Francis Barber, to whom he would leave the residue of his estate.

In clarification of the Navigation Acts’ requirement that all merchandise must be transported to and from the colonies in British ships, the Solicitor General had ruled in 1677 that ‘negroes ought to be esteemed goods and commodities’ under the law.[34] But while the institution of slavery was woven into the fabric of colonial law, its status was not so certain in the mother country. According to one famous Elizabethan ruling, England was ‘too pure an Air for Slaves to breath in’, and many contradictory opinions had since been offered up.[35] In 1749, Lord Chancellor Hardwicke pronounced that a slave in England was ‘as much property as any other thing’; whereas in 1762, Lord Chancellor Henley declared that ‘as soon as a man sets foot on English ground he is free’.[36] It seems baffling that such men, the greatest legal minds of their time, could be so changeable in their judgements on a question that could surely be seen as none other than the choice between right and wrong.

In September 1767, David Laird, the captain of one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s ships, the Thames, was caught up in a dispute arising from the ambiguous status of a human ‘commodity’ destined for Jamaica. The episode had its origins two years earlier, however, when Granville Sharp, a clerk in the ordnance department based at Tower Hill, found a young black man of about sixteen injured outside the Mincing Lane premises of his brother William Sharp, a surgeon well known for treating the poor. It seemed that David Lisle, a lawyer who had brought the youth – whose name was Jonathan Strong – from Barbados, had beaten him with a pistol so repeatedly that he had almost lost his sight and could hardly walk. William Sharp had Strong admitted to St Bartholomew’s Hospital; Granville Sharp later found work for him as the delivery boy for an apothecary on Fenchurch Street.

One day during the summer of 1767, Lisle spotted Strong by accident and tricked him into entering a public house. There, backed up by two burly officials, he sold him to James Kerr, a sugar planter who was one of Mure, Son & Atkinson’s clients. Kerr insisted he would only pay the £30 purchase price once Strong was securely on board the Thames, which was then preparing to sail for Jamaica. In the meantime the young man was thrown into the Poultry Compter, one of several small prisons dotted about the City. It was from here that, on 12 September, Granville Sharp received Jonathan Strong’s letter begging for help.

Sharp called upon Sir Robert Kite, the Lord Mayor, in his capacity as London’s chief magistrate, and requested that all those with an interest in Strong should argue their claims in open court. At the hearing on 18 September, Captain Laird and James Kerr’s lawyer both insisted that the young man belonged to Kerr by virtue of a signed bill of sale. After heated debate, Kite stated that ‘the lad had not stolen any thing, and was not guilty of any offence, and was therefore at liberty to go away’. Laird immediately grabbed Strong by the arm, saying that ‘he took him as the property of Mr. Kerr’, whereupon Sharp threatened to have him arrested for assault. Laird released Strong’s arm, and all parties left the courtroom, including Strong, ‘no one daring to touch him’.[37] Kerr subsequently pursued a court action against Sharp, seeking damages for the loss of his property; he persevered with the suit through eight legal terms before it was dismissed.

The thought that right here, on the streets of London, black people could have been lawfully snatched, sold and transported against their will to the colonies, seems almost unfathomable today; but such was the reality of the Atlantic empire. This particular incident was noteworthy only in that it galvanized the man who would come to be seen as the father of the anti-slavery campaign, twenty years before Wilberforce and Clarkson took up the cause. Granville Sharp subsequently became a formidable expert in habeas corpus, and his book, A Representation of the Injustice and Dangerous Tendency of Tolerating Slavery, would be the first major work of its kind by a British author. Which is how, in a blink-and-you-missed-it kind of way, Richard Atkinson came to be a bystander at the dawn of the abolition movement.

FOUR

Four Dice

THIS WAS AN AGE of polymaths, a time when gifted amateurs made strides in the fields of astronomy, botany, chemistry, mechanics and physics. Two of Richard Atkinson’s closest friends in the early 1770s were George Fordyce and John Bentinck, both Fellows of the Royal Society, founded in 1660 for the purpose of ‘improving natural knowledge’. Fordyce, a physician and lecturer in chemistry at St Thomas’s Hospital, was also a member of Samuel Johnson’s Literary Club, where his shambolic manner inspired various anecdotes. On one occasion, following a bibulous dinner, Fordyce was supposedly called out to attend to a fine lady. Unable to locate her pulse, he muttered under his breath ‘Drunk, by God!’; the next day he received a letter from his patient containing £100, begging him not to disclose the intoxicated state in which he had found her. Bentinck, a naval captain, was also a skilled engineer, best known for developing a ship’s pump that became standard issue throughout the Royal Navy. Some believed him underrated; Benjamin Franklin thought his ‘ingenious Inventions’ had not always ‘met with the Countenance they merited’.[1] Captain Bentinck would die in his thirties, in 1775 – Richard was his executor.

Robert Erskine was another engineer who was much in Richard’s orbit around this time. He had moved to London from Edinburgh in the mid-1750s, and for six years had used Hutchison Mure’s premises as his postal address in the capital. Erskine’s talents as an inventor seem to have been offset by bad luck in his financial dealings; in 1762 he was briefly committed to the debtors’ prison. Soon afterwards he began work on a new pump, calling it the ‘Centrifugal Hydraulic Engine’.[2] Only two were ever sold – one to the Venetian ambassador and the other for use in a salt mine belonging to the King of Prussia – and when Erskine fell out with an investor over their losses, Richard and his friend Captain Bentinck stepped in as arbitrators. Subsequently Erskine set up as a surveyor with a particular expertise in hydraulics, and established a practice at Scotland Yard in Westminster. By 1770, the year that he published ‘A Dissertation on the Rivers and Tides, to Demonstrate in General the Effects of Bridges, Cuttings, or Imbankments, and particularly to Investigate the Consequence of such Works, on the River Thames’, he had acquired some impressive clients, and his luck – like the tide – seemed to be turning.

Richard, however, had other plans for Erskine. Since 1765, Mure, Son & Atkinson had been part-owners of an ironworks at Ringwood, New Jersey, about forty miles north-west of New York. This enterprise had started at great tilt a few years earlier under its founder, Peter Hasenclever; by the summer of 1766 its assets included four blast furnaces, seven forges, ten bridges, thirteen mill ponds and more than two hundred workers’ dwellings. Before long, Hasenclever had run through the £54,000 capital he had raised in England to fund the venture. He returned to London in November 1766 after learning that one of his partners had declared bankruptcy. In May 1767 Richard Atkinson was appointed a trustee of the business; Hasenclever was demoted to the position of agent, and soon resigned in disgust.

Following Hasenclever’s departure, the ironworks struggled. The trustees’ monthly letters of instruction to Reade & Yates of Wall Street, their New York agents, carrying Richard’s signature as the managing partner in London, are a sorry catalogue of setbacks. Disobeyed instructions, delayed shipments, impatient creditors and accounting discrepancies – such are the perennial frustrations of long-distance business relationships. By January 1770 the trustees distrusted both the ironworks’ managers, one of whom had been caught embezzling their money, and the other squandering it. ‘An honest & a capable man is what we want,’ they told Reade & Yates.[3] Robert Erskine answered such a description – but it is something of a mystery why he accepted Richard’s invitation to cross the ocean to run a failing ironworks. Perhaps he perceived the American colonies as a place where he and his wife, who had recently lost their only child, might start again; maybe the salary of two hundred guineas, plus 5 per cent of the profits, was after years of financial troubles too powerful a lure to resist.

To remedy his lack of experience in the iron trade, Erskine gave himself a crash course in its practicalities during the autumn of 1770, when he spent two sodden months touring Britain’s most prominent ironworks, including Coalbrookdale in Shropshire and the Carron Company in Stirlingshire. Often he turned up at sites unannounced, finding workmen more than happy to show him round in return for a few shillings. (‘A very agreeable present to men who with families of 6 or 7 Children earned only 12s. a Week,’ he would observe.)[4] Along the way, Erskine gathered dozens of lumps of iron ore which he boxed up and sent back to London for chemical analysis by George Fordyce.

Every few nights, by the guttering candlelight of his lodgings, he wrote a long letter to Richard in London, describing all he had seen; thirteen of these dispatches have survived, and they paint a vivid picture of iron production at the start of the industrial revolution, as the charcoal furnaces producing soft, malleable iron suitable for the blacksmith’s forge were superseded by the hotter coke-burning furnaces of the coalfields. At Bersham in Denbighshire, for example, Erskine watched white-hot iron flowing from a furnace into the sand mould for one of fifty cannons ordered by the King of Morocco, protecting his eyes from the glare by ‘Cutting a small hole in a letter and looking through it’, and observed the barrel of another cannon being bored by a drill bit fixed to the axis of a water wheel, a procedure that ‘made a very disagreeable noise which at a distance was much like that of Geese’.[5]

In late October, en route to Scotland, Erskine broke his journey at Temple Sowerby. During his stay, perhaps seeking respite from George and Bridget Atkinson’s noisy brood, he worked out the height of Cross Fell, using his quadrant and a dish of mercury to provide a reflective ‘false horizon’. It was a rare cloudless day. ‘The Old Gentleman was so civil as to remain uncovered,’ he told Richard, referring to the mountain, ‘which was the more polite, as he had not been so long bare headed for many days before.’ By Erskine’s reckoning, Cross Fell stood 3,731 feet above the meadow by the bridge over the River Eden; while a benchmark chiselled into one of the quoins of Temple Sowerby church states the village itself to be 348¾ feet above sea level. He believed his measurement to be ‘pritty accurate’, but it turns out he was off by more than a thousand feet, for Cross Fell in fact stands 2,930 feet tall.[6]