Mr Atkinson’s Rum Contract

THE BANKING CRISIS of 1772 was short-lived, but its ill effects would soon ripple around the empire, bringing a spell of optimism in the Atlantic economy to a close. Many American merchants found themselves with warehouses full of goods imported from Britain, and debts they could no longer discharge. This, in turn, ruined many businesses in the mother country. One British politician would later observe that the long credit terms allowed to merchants in the colonies, and the difficulty of recovering debts from them, had ‘made bankrupts of almost three-fourths of the merchants of London trading to America’.[41]

Despite Robert Erskine’s best efforts, the ironworks at Ringwood continued to test Richard and his fellow trustees’ patience, and they finally resolved to put it up for sale. Advertisements appeared in the New-York Gazette in September 1772, but there were no takers. Meanwhile they instructed their American agents to sell off their pig iron warehoused in New York ‘as fast & as far’ as possible, only to find that Reade & Yates, themselves in deep financial trouble, had been stockpiling it for use as a currency with which to settle their own bills. ‘Had your object been to destroy us as a Company,’ the trustees wrote in December 1772, ‘you could not have held a Conduct more likely to effect your Purpose.’[42]

Richard would with hindsight look back on 1772 as a year of ‘horrors’. On a personal level, he had been working towards a larger share of the partnership, which he had hoped might assist a cause as yet unarticulated, but extremely close to his heart. Alexander Fordyce’s bankruptcy not only demolished Richard’s ‘castles in the air’. It also had consequences that would ultimately lead to a great diminution of the Atlantic empire.

FIVE

All the Tea in Boston

TWICE A YEAR, great auctions of tea and other luxurious goods took place at the headquarters of the East India Company in London. The Bank of England invariably granted the Company a short-term loan before each sale, to ease its cash flow as it waited for accounts to be settled – £300,000 was the sum advanced in the spring of 1772. But with many merchants unexpectedly strapped for funds that summer and unable to pay their bills, even the almighty East India Company was snared in the financial crisis. When the Company defaulted on a payment to the Treasury in August, its wobbling finances became public knowledge and its stock price started to slide; within weeks it had tumbled from £225 to £140. The collapse, of course, came too late for Alexander Fordyce; had he been able to hold out till then, as one journalist pointed out in late September, he would have made as much money ‘as not only would have settled all his affairs, but have left an handsome fortune for life’.[1]

The East India Company’s problems stemmed partly from the American public’s widespread reluctance to consume its tea. Back in 1767, after the repeal of the Stamp Act, parliament had introduced taxes on various items – glass, paint, lead, paper and tea – imported into the colonies. While bearing a superficial resemblance to the taxes used to regulate the flow of trade throughout the British empire, the purpose of these so-called ‘Townshend duties’ (named after Chancellor of the Exchequer Charles Townshend, their originator) was to raise money for the Treasury, which made them quite as unpalatable to many colonists as the Stamp Act.

The Americans had retaliated against the duties with the powerful weapon of non-importation, which kept out around 40 per cent of British imports. Their tactic worked. In April 1770, shortly after Lord North became prime minister, all the duties were repealed, apart from the one on tea – which was kept in order to assert parliament’s authority to raise tax from the colonies. After the subsequent collapse of the non-importation movement, goods from the mother country flooded the colonies. Even so, contraband Dutch tea continued to dominate the American market; less than a quarter of the tea consumed there came through legal British channels. By the end of 1772, there were said to be seventeen million pounds of surplus leaves rotting in the East India Company’s warehouses around the City of London.

The British government had for some time wished to rein in the overbearing East India Company, and its financial woes provided Lord North with vital leverage. Through the Regulating Act, passed in June 1773, ministers gained some control over the management of India; in return, the Company was granted a loan of £1,400,000, as well as concessions to help reduce its tea mountain. Under the Tea Act, all duties previously charged on leaves imported to Britain and then re-exported to America were cancelled; the saving could be passed on to consumers. Suddenly, a pound of the Company’s fully taxed tea cost Americans a penny less than the smuggled variety. Ministers were confident that the lower prices would persuade American consumers to swallow their pride, but they were quite wrong; the colonists saw the Tea Act for what it was, a clumsy attempt to trick them into accepting the Townshend duty and thus the principle of parliamentary taxation.

On 20 August 1773, Lord North and his Treasury Board issued a licence for the export of 600,000 pounds of tea to the ports of Boston, New York, Philadelphia and Charleston. The Dartmouth, laden with 114 chests of tea, entered Boston harbour on 28 November; from then its captain had twenty days to pay the duty on his cargo, or else the vessel would be impounded. Leading merchants of the town, insisting that the tea must be rejected, requested a special clearance to allow the ship to leave port without unloading its cargo – but the governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson, declined to grant permission. Soon two more vessels filled with tea arrived from London and moored alongside the Dartmouth.

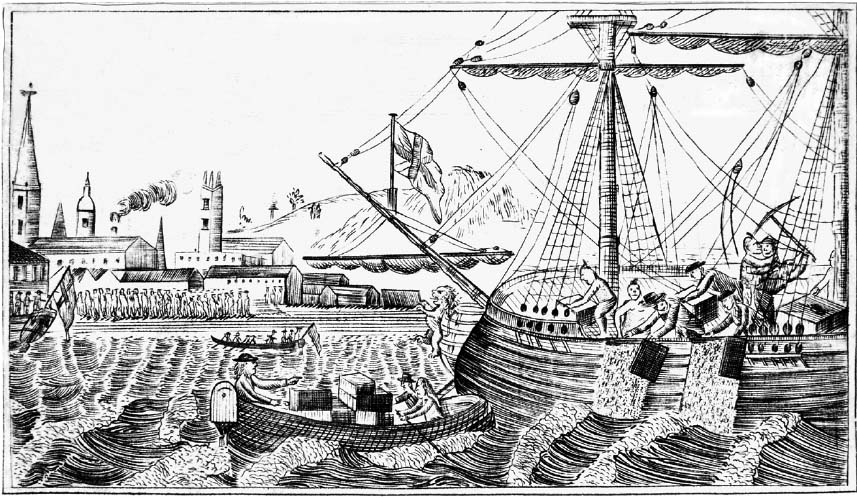

The ‘Mohawks’ empty the tea chests into Boston harbour.

Granger Collection/Bridgeman Images

On 16 December, the day before the Dartmouth’s customs payment was due, a crowd of several thousand gathered to hear the ship’s owner, a local merchant, reveal that Governor Hutchinson remained adamant in his refusal to let it depart. As the meeting broke up in the late afternoon, a number of men dressed as ‘Aboriginal Natives’, their faces blackened with coal dust, ‘gave the War-Whoop’, a pre-arranged signal to hurry to the three vessels.[2] Over several hours, by the light of lanterns, these self-styled ‘Mohawks’ smashed open 342 chests of tea and threw them overboard. Next morning, at high tide, the broken-up tea chests could be seen bobbing above a vast slick of briny sludge that stretched across the bay.

BRITISH PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS during the eighteenth century were notorious for their bribery, bullying and other skulduggery – sins which could undoubtedly be laid at the door of Sir James Lowther, who owned great tracts of Cumberland and Westmorland, and whose sense of entitlement was so inflated that he saw the parliamentary seats returned by those counties, and all the boroughs within, as his personal property.

Much more importantly – at least for the purposes of this story – John Robinson was Lowther’s law agent, land steward and chief stooge. Born in 1727 the son of an Appleby draper, Robinson had been articled to his uncle Richard Wordsworth, attorney-at-law to the Lowther family, at the age of seventeen. Over the years he had upset numerous people while executing his employer’s orders, and many blamed the ‘dirty attorney of Appleby’ for the baronet’s obnoxious behaviour in general.[3]

Lackey though he may have been, John Robinson did not lack political ambitions of his own. In January 1764, he was returned through Lowther’s influence as MP for the county of Westmorland. He would (at least in the beginning) faithfully support his patron’s interests, while forging a close friendship with another of Lowther’s men, Charles Jenkinson, the MP for Cockermouth, who was at that time Secretary to the Treasury. In 1765 Robinson acquired a long lease on the White House in Appleby, which he remodelled in Venetian style; its ogee-arched windows remain to this day an incongruously exotic feature of the town’s handsome main street.

George Atkinson was only three years younger than Robinson, and they must have moved in overlapping local circles; so it seems likely that they were already well acquainted when, in 1769, George applied to Robinson to sponsor a parliamentary bill permitting the enclosure of the common at Temple Sowerby. Indeed, Robinson may have urged George to make the application – for the enclosure of common land was a well-worn method of forging political allegiances, through the creation of freeholders who would gain the franchise. George had hitherto been ineligible to vote, for what land he owned was held under a thousand-year lease from the lord of the manor, Sir William Dalston. It certainly served Sir James Lowther’s interest to facilitate the enclosure at Temple Sowerby, for he was at the time tussling with the Duke of Portland for political supremacy in the area. Dalston, for one, detected mischief in the scheme. ‘The Lowtherians Resentment is so great,’ he told the duke, ‘as to spirit up my Lease-hold Tenants of Temple Sowerby to the Honourable House of Commons against me, for liberty to take up a large Quantity of waiste Ground where I am Lord, without consulting or acquainting me with it, and directly against my Opinion.’[4]

John Robinson’s focus shifted from Westmorland to Westminster in 1770, on his appointment as Secretary to the Treasury under Lord North. The new prime minister – whose courtesy title, as the heir to an earldom, meant that he sat in the Commons, not the Lords – was one of the warmest men in politics, with a quick wit and a nice line in self-deprecation. In his appearance, North cut a clumsy figure, of which Horace Walpole offered this uncharitable description: ‘Two large prominent eyes that rolled about to no purpose (for he was utterly short-sighted), a wide mouth, thick lips, and inflated visage, gave him the air of a blind trumpeter.’[5]

Robinson had been warned that his post at the Treasury would involve ‘a Sea of Troubles’, and it certainly required the mastery of several briefs.[6] There was the nation’s financial administration, which tied him up in correspondence with officials throughout the land; there were twice- or thrice-weekly Treasury Board meetings, chaired by Lord North, after which Robinson was responsible for issuing all the necessary orders, contracts and payments of money; and there was the role of chief whip in all but name, through which he managed the prime minister’s parliamentary business. Although the Secretary to the Treasury operated behind the scenes, he wielded great influence.

In the spring of 1773, four years after George Atkinson’s application, Robinson at last placed his private bill to enclose ‘Temple Sowerby Moor’ before parliament; royal assent was granted on 28 May.[7] Now the commissioners appointed to oversee the division of the common could get to work. The 360 acres were distributed between the heads of twenty-four households in Temple Sowerby, and the resulting fields demarcated with hawthorn saplings; the area was then mapped out on parchment and executed as a legal document. George, who bankrolled the process, was allotted fifteen acres in lieu of his expenses, taking his overall share of the land to fifty-one acres.

GEORGE III OPENED PARLIAMENT on 13 January 1774 with a ‘gracious speech’ outlining his government’s priorities for the coming session.[8] News of the Boston ‘tea party’ arrived a week later, however, and the unruly state of the American colonies suddenly trumped all other concerns. On 29 January, the cabinet agreed that strong measures would be needed to bring the colonies back into line; as a result, the passing of a series of ‘coercive’ acts would occupy parliament over the coming months.

Lord North announced the measures that would be contained within the Boston Port Act on 14 March; the town’s harbour would be shut up for business until its people had made ‘full satisfaction’ to the East India Company for the destruction of the tea.[9] The House of Commons almost unanimously welcomed the legislation; even Colonel Barré, a hero to the Sons of Liberty, gave it ‘his hearty affirmative’.[10] Three more coercive acts were nodded through before the summer recess, one of which revoked Massachusetts’ 1691 charter and restricted the people’s right of assembly; another allowed the governor to move a trial to Britain if he believed a fair hearing was unlikely in the colony; and a third permitted uninhabited houses, outhouses and barns to be requisitioned as accommodation for British soldiers. Meanwhile a law extending the boundaries of Canada, and guaranteeing the free practice of Catholicism there, angered many Americans, who saw it as an assault on their territory and their faith.

The ‘intolerable acts’, as they soon became known throughout the thirteen colonies, turned hordes of wavering loyalists against the mother country. In New Jersey, Robert Erskine continued to enjoy a frank correspondence with Richard Atkinson – ‘I write to you as a brother & as a friend, and it is a relief to give you my sentiments naked open & undisguised,’ he wrote on one occasion – but from this time onwards, his tone is one of noticeable disaffection.[11] ‘I have had a great deal too much business on my own hands to think of, much less to write on politicks till now,’ he wrote in June 1774, ‘but things draw fast to a Crisis if the news be Confirmed that an obsolete Act of Henry the VIII is to be extended to this Country whereby people obnoxious to the Governor here or Government at home may be transported for trial to Britain. I have no doubt that a total suspension of Commerse to and from Great Britain and the West Indies will Certainly take place.’[12]

THESE ILL WINDS from America did not entirely blow the domestic agenda off course during the parliamentary session of 1774. As the king had heralded back in January, his government introduced bold measures to improve the ‘state of the gold coin’, and not before time, because guinea, half-guinea and quarter-guinea coins had become so debased – through ‘clipping’ (filing metal from a coin’s circumference) and ‘sweating’ (collecting metallic dust from coins shaken in a bag) – that they were on average one-tenth lighter than their legal weight.[13] The Recoinage Act passed on 10 May 1774; by a Royal Proclamation pinned to the door of every church in the land, the order went out that all ‘light’ gold should be passed over to the official collectors for the district. They would take it at face value, cut and deface it, and transport it to the Bank of England in London, returning with pristine coin of the correct weight. Over the following four years, gold coins worth £16,500,000 would be renewed by this process.

John Robinson ran the operation out of the Treasury in Whitehall, commissioning 130 local money changers and settling terms with them. It was necessary that they should be men of substance, since the payments they would make to those handing in defective coins would need to come out of their own coffers – they would be reimbursed for their services later. ‘The Allowances are from a third to one per cent in lieu of all risque, trouble, loss of Interest and Expences,’ Robinson told prospective changers.[14] He appointed George and Matthew Atkinson to oversee the recoinage in Westmorland; the county was so remote from the capital that he allowed them a special commission of 1¼ per cent on all the money they exchanged.[15]

Robinson’s choice of the Atkinson brothers for his home county may have been rooted in old acquaintance, but they were also eminently qualified for the task, for banking had overtaken tanning to become their primary line of business. The difference between the two occupations was not so great as it might sound, for tanning was a capital-intensive trade, and large sums of money passed through the brothers’ books. Moreover, they permitted their customers what would these days be considered excessively long payment terms – often a year or more – and it was a relatively small leap from providing credit to offering bank accounts.

During the early stages of the industrial revolution, when coin was often scarce, manufacturers regularly relied on brokers to convert the bills of exchange that they received for their goods into gold and silver with which they could pay their workers. Since the 1750s, George and Matthew Atkinson had been performing this service for the proprietors of Backbarrow ironworks, at the southern tip of Lake Windermere, where it was the custom to hold a grand payday at the feast of Candlemas. Every year, in January, the partners of the ironworks would make the eighty-mile round trip to Temple Sowerby to exchange paper bills for coin; the delegation generally consisted of at least half a dozen armed men, passing as it did through some truly desolate terrain. Towards the end of 1774, however, gold was in such universally short supply – £4,500,000 had been withdrawn from public circulation over the summer – that the Atkinson brothers’ usual banking contacts in Newcastle and Glasgow could not provide the £14,000 in coin needed for the Backbarrow payday.

Over the autumn, George had conveyed several loads of ‘light’ gold – on two occasions, more than £20,000 – down to London to be recoined, and he now proposed to his friends at Backbarrow a scheme that would have to be kept secret. He wrote from Temple Sowerby:

The only method that we can think of to be on a certainty is to fetch about £8000 from London in this way – that two of your people must come here the 29th day of January with all the bills that have come to your hands then, and they shall have £4000 home with them next day. And I will go off in that night, fly to London, get there on Wednesday night, stay Thursday and Friday to get the bills discounted, and set out on Saturday or Sunday morning and be here on the 8th or 9th with as much as will make your payments easy. The only objection to this plan is the short days and dark moon, and to balance that we will take 4 days to come down instead of 3 which was our limited time last August, and after one is 60 or 80 miles from London the danger of robbery is over.[16]

Such a mission entailed a good deal of risk, for the lonely roads surrounding the capital were haunted by highwaymen legendary for their brazenness; only two months earlier the prime minister had himself been held up at gunpoint and relieved of his pocket watch and a few guineas.

LORD NORTH CALLED a general election in September 1774, six months sooner than strictly necessary, for it made sense to get this business out of the way – a ‘Continental Congress’ had recently assembled at Philadelphia to debate the colonies’ collective response to the ‘intolerable acts’, and trouble was looming. John Robinson assisted the prime minister with the purchase of seats for those men whose presence in the House of Commons the ministry deemed necessary. (With patrons of ‘pocket boroughs’ demanding around £3,000 per seat, the Treasury spent nearly £50,000.) Sir James Lowther, having quarrelled with Robinson, chose to represent Westmorland himself – George Atkinson, as a newly minted freeholder of the county, dutifully awarded Lowther his vote.[17] Robinson secured a Treasury-sponsored seat at Harwich in Essex.

Twelve of the thirteen American colonies, all apart from Georgia, sent delegates to the First Continental Congress; the sibling territories had not always agreed, but their anger towards the mother country now bound them together. ‘The Oliverian spirit in New England is effectually roused and diffuses over the whole Continent,’ Robert Erskine wrote to Richard Atkinson on 5 October. ‘The rulers at home have gone too too too far: the Boston Port Bill would have been very deficient of digestion, but Altering Charters, the due course of justice & the Canada Bill are emitents which cannot possibly be swallowed and must be thrown up again.’[18]

Congress published its resolutions on 20 October. The import of any goods from Britain, and sugar, coffee or pimento from the British West Indies, would be banned almost immediately, and no American goods would be sent to Britain or the West Indies after 10 September 1775 unless the coercive acts were repealed. On its final day, Congress issued a ‘loyal address’ to the king, listing its grievances in carefully deferential language; but since His Majesty viewed Congress as an illegal body and the imperial relationship as non-negotiable, he did not see fit to dignify the petition with a response.

The West India lobby took particular fright at the resolutions of Congress, since sugar planters looked to the American colonies for much of the basic food on which their enslaved workforce subsisted. On 18 January 1775, more than two hundred men gathered at the London Tavern to discuss what to do next; Richard was present, and he argued firmly (but with little effect) against a proposal to send parliament a petition warning of the calamity threatened by the resolutions, pointing out that since it ‘was only meant to recommend to the consideration of Parliament, what Parliament would certainly consider of themselves, it was a futile measure’.[19] His assertion would be proved correct. The government, inundated with merchants’ entreaties on the subject, set up a special panel for their assessment, which was dubbed the ‘Committee of Oblivion’. It was two months before the West Indians’ petition reached the top of the pile; by this time the ministers had already made the policy decisions that the petitioners had been hoping to influence.

It was alarming that West Indian planters should rely so much upon American grain and rice, and crucial that a substitute for these starchy crops was found – one that would grow on the islands. Thus, in March 1775, the Society of West India Merchants announced the reward of £100 for anyone who brought ‘from any part of the World, a plant of the true Bread Fruit Tree, in a thriving Vegetation, properly certified to be of the best sort of that Fruit’.[20] Captain Cook had enthused about this plant after visiting Tahiti five years earlier. ‘The fruit is about the size and shape of a child’s head,’ he had written, a rather unsettling description. ‘It must be roasted before it is eaten, being first divided into three or four parts: its taste is insipid, with a slight sweetness somewhat resembling that of the crumb of wheaten-bread mixed with a Jerusalem artichoke.’[21]

BOSTON, THE HUB OF colonial discontent, remained calm for the time being. ‘The winter has passed over without any great Bickerings between the Inhabitants of this town and His Majesty’s Troops,’ General Thomas Gage reported to Lord Dartmouth, the Colonial Secretary, on 28 March 1775.[22] Two weeks later, though, Gage received orders from Dartmouth to use force in disarming any rebels. Before dawn on 19 April, seven hundred soldiers marched from Boston to seize a stockpile of weapons from the village of Concord, some seventeen miles away. The mission was meant to be secret, but everyone living along the route had somehow been alerted. At Lexington, a skirmish blew up between redcoats and rebel militia that left eight local men dead. By the time the British reached Concord, the colonists’ stash was no longer in evidence; and as they withdrew, a running battle started that continued all the way back to Boston. Harassed by crossfire, about 250 redcoats were either killed or wounded, versus ninety rebel casualties.

These clashes signalled a new escalation of the conflict. Within days, an army of fifteen thousand rebel volunteers had mustered to block access to the peninsula on which Boston was built, and where the British were garrisoned. On 3 May, Robert Erskine informed his employers in London that he had received an application for gunpowder from the ‘principal people of the County of Borgen in the Jerseys, in which your Iron Works are situated’, and that these men were forming a militia to defend themselves against the British. He no longer believed that a reconciliation between America and the mother country was possible – unless, that is, ‘Blood seals the Contract’.[23]