Mr Atkinson’s Rum Contract

I LIKE TO IMAGINE Bridget and Richard, the two pivotal characters in this story, standing side-by-side in the crowd that watched George III travel in his golden coach to the House of Lords to close parliament on 23 May 1776. (I cycle along the processional route, past St James’s Park, on my way into work every day.) The king addressed his subjects solemnly on that occasion, expressing regret that he had recently found it necessary to ask his ‘faithful Commons’ for extra money to pay for the American conflict, and still holding out hopes that his ‘rebellious subjects’ would yet be ‘awakened to a sense of their errors’.[13]

But it was too late for that. In Philadelphia, on 4 July, Congress ratified the final text of the ‘unanimous declaration of the Thirteen United States of America’. The document, which started by stating the ‘self-evident’ truth that all men were ‘created equal’, went on to list the ‘Injuries and Usurpations’ to which the colonists had been subjected, before drawing the following conclusion: ‘A Prince, whose Character is thus marked by every Act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the Ruler of a free People.’[14] The text was in large part drafted by the Virginia planter Thomas Jefferson, and its pretensions to moral authority did not go unchallenged. ‘If slavery be thus fatally contagious,’ pondered Samuel Johnson, ‘how is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of negroes?’[15]

The withdrawal of British forces from Boston in March 1776 had left them without access to a port between Nova Scotia and Florida. Now the British high command aspired to make New York their headquarters, since it held the key to the American interior, as the gateway to the mighty Hudson River; for the time being, though, the Continental Army controlled the island of Manhattan. General Howe sailed from Nova Scotia with nine thousand men, seizing Staten Island – five miles south of Manhattan – at the end of June. Two weeks later Admiral Howe, the general’s brother, arrived at the head of a fleet carrying eleven thousand troops. Thirteen thousand more would soon follow, including a large contingent of Hessians – German mercenaries hired to serve alongside the redcoats.

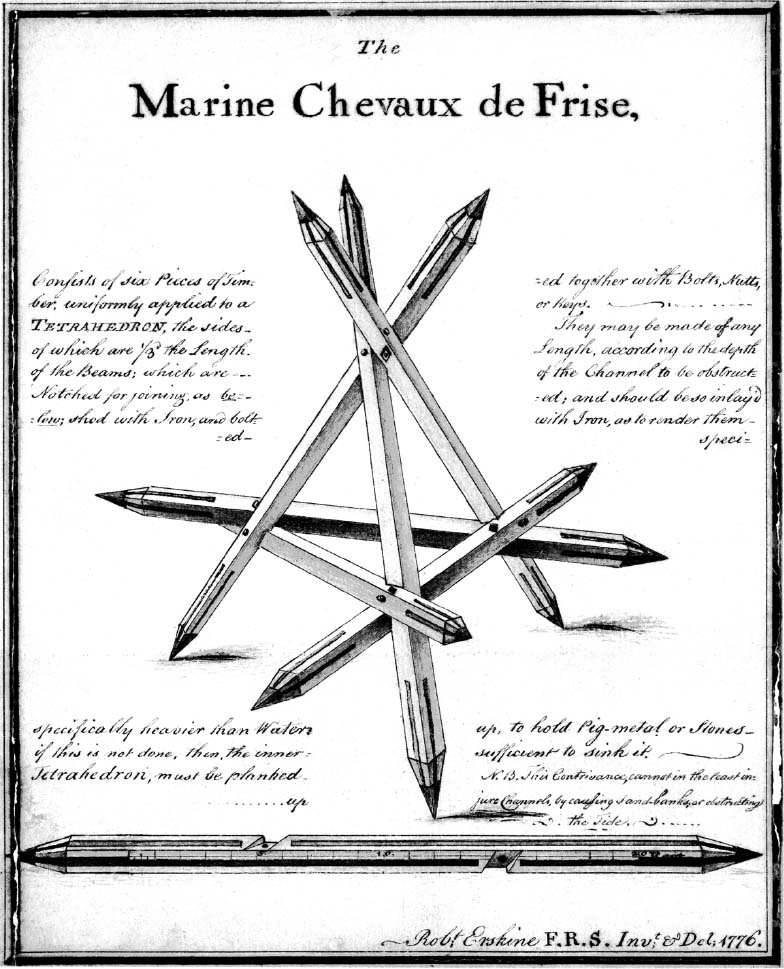

When Robert Erskine learnt, on 12 July, that five British warships had outrun rebel batteries defending the mouth of the Hudson, and were now anchored only twenty miles from Ringwood, he set to work on a contrivance to prevent further incursions. Erskine’s ‘Marine Chevaux de Frise’ – along the same lines as the wooden frames with spikes that were used to head off cavalry charges – was a tetrahedron made of oak beams tipped with iron points that would pierce the hull of any ship passing over it. Eight days later, he presented a scale model for General Washington’s inspection; he also wrote to Benjamin Franklin in Philadelphia, offering it for use on the Delaware River. In the end, similar devices of a rival design were used to defend the Hudson, although it appears that the ironworks at Ringwood provided the spikes – Erskine’s cash book records a debit of £1,022 against ‘the United States’ for eleven tons supplied to make ‘Chevaux-de-frise’.[16]

Robert Erskine’s device to prevent the British from penetrating the Hudson River.

American Philosophical Society

During the autumn of 1776, the British advance seemed almost unstoppable. Four thousand redcoats landed at Kip’s Bay, on the east side of Manhattan, on 15 September; within hours they had taken New York. By the end of November, General Howe was confidently predicting the expulsion of the Continental Army from New Jersey; this territory, with its abundance of ‘covering, forage, and supplies of fresh provisions’, would make fine winter quarters for his troops.[17] ‘I think the game is pretty near up,’ General Washington told his brother on 18 December. ‘No Man, I believe, ever had a greater choice of difficulties and less means to extricate himself from them.’[18]

A week after writing these words, on Christmas night, Washington led a straggling column across the icy Delaware River. The next morning, after a short battle, they captured two-thirds of the Hessian brigade garrisoning the small town of Trenton, New Jersey. This modest victory marked a turnaround for the rebels; another morale-boosting win followed ten days later at Princeton. Howe’s hopes that his army might achieve self-sufficiency were dashed; from now on, he told the Treasury Board, all provisions must come from Britain – since America could be relied upon for nothing.

‘WE ARE IN FORCE sufficient to enter upon offensive Operations,’ General Howe had written to ministers in London on 6 August 1776, ‘but I am detained by the Want of Camp Equipage, particularly Kettles and Cantines, so essential in the Field, and without which too much is to be apprehended on the Score of Health.’[19] Consequently, on 14 September, the Treasury ordered Richard Atkinson to supply ‘barrack furniture’ for 25,000 men, uniforms for 5,000 loyalist militia, and a pair of ‘thick milled woollen mittens for every man’, as well as to ‘take up & arm shipping sufficient to carry the whole together with the Camp Equipage Shoes Stocking & Linnen for the next Campaign’.

Richard’s clerks immediately set about sourcing thousands of beds, bolsters, blankets, candles, candlesticks, rugs, pokers and tongs. ‘We are obliged to obtain goods of all Sorts from the Makers as matter of favor & preference,’ he commented, ‘whilst their workmen are universally Engaged in Combinations & all the Licentiousness arising from a Superabundance of employment.’[20] (A collective demand for improvements in pay or conditions was known as a ‘combination’.) With winter coming, shortcuts were needed, and Richard warned General Guy Carleton, commander-in-chief in Canada, that he had ordered 30,000 yards of ‘legging dyed at Leeds to be sent unpressed’; the material might seem coarser than usual, but it would not be any ‘less durable or less warm’.[21]

The sheer unpredictability of the business of provisioning the army in America was already abundantly clear. The idea that each of the Treasury’s ships would make two return crossings a year had proved hopelessly optimistic. In August 1776, a westerly wind confined several Canada-bound ships to the English Channel for three weeks, giving rise to fears that they would fail to reach Quebec before the annual freezing of the St Lawrence River. Such setbacks were intensely stressful for all concerned. ‘I am sorry to find Lord North by his letter so uneasy at all the Victualling ships being not yet sailed for Canada,’ the king wrote to John Robinson, ‘as I attribute part of it to his not being in good spirits.’[22] By 26 September, when the last of the twenty-nine ships destined for Quebec that year sailed from Cork, Richard and his partners in the Canada contract had supplied 591,500 pounds of salt beef, 2,366,000 pounds of salt pork, 3,458,000 pounds of flour, 1,274,000 pounds of bread, 253,496 pounds of butter, 610,985 pounds of oatmeal, and 27,420 bushels of peas for the consumption of the troops.

The mounting cost of feeding the army soon began to attract scrutiny. Richard’s name was not mentioned during a robust parliamentary debate about the subject on 21 February 1777 – surprisingly, perhaps, given that more than one-third of the Treasury’s expenditure on the war over the previous year had passed through his books and those of his various partners. Colonel Barré did, however, observe that 5s 3d per gallon for the 100,000 gallons of Jamaican rum supplied by Richard was a ‘most unheard of and exorbitant price’ – but Lord North insisted it had ‘left little or no profit for the contractor’.[23]

The prime minister’s annual budget, delivered on 14 May, revealed a shortfall of £5 million that would have to be met with a public loan. When, by way of response, the opposition launched a stinging attack on the cost of the war, Colonel Barré returned to the cost of the rum; the contractor, he suggested, must be a ‘very good friend of the treasury indeed’. Not so, said Lord North: ‘The contract with Mr. Atkinson was for rum of the very best proof, the finest that could be had in Jamaica.’ Indeed, he continued, once freight, leakage, insurance and commission were taken into account, the 5s 3d agreed by the Treasury Board, ‘so far from being a bad bargain, was evidently a very favourable one’. Barré replied sarcastically that on such terms the poor contractor ‘must be ruined’, and it was cruel of the Treasury to treat him so unfairly: ‘He now plainly saw the reason why people of all sorts were so shy of taking government contracts. But this Mr. Atkinson must be the greatest idiot in the whole contracting world: did he make his contracts for sour crout and porter upon the same principles?’[24]

At one point during these proceedings Lord North tripped over his numbers and confessed that he was not certain whether the values he was quoting were in pounds sterling or Jamaica’s local currency – a hugely embarrassing slip-up. Afterwards the Morning Post gossiped that Sir Grey Cooper – John Robinson’s fellow Secretary to the Treasury, who sat beside the prime minister during debates and was meant to feed him with facts and figures – had received a ‘private whipping’ for the blunder.[25]

Decisive action was clearly needed to head off a brewing political scandal. The next time Richard was summoned before Lord North and his Treasury Board, on 3 June, it was agreed that some independent merchants should be asked to evaluate whether the rum might reasonably have been cheaper and, if so, how much it ought to have cost. Beeston Long, the chairman of the Society of West India Merchants, and two other City of London grandees, were appointed referees.

THE TREASURY BOARD had already given General Howe the go-ahead to order more rum direct from the merchants who had shipped such large amounts of it to New York during the summer of 1776. It was typical that Richard should have been the only one of the five original suppliers who was far-sighted enough to appoint an American agent. He wrote to Howe on 14 January 1777 offering to furnish as much rum as necessary: ‘We have by various Conveyances ordered our Agents in Jamaica to secure a sufficient Quantity to enable them to execute your Excellency’s Commands to what extent soever they may receive them.’[26] The same day he informed Joshua Loring, the merchant acting as his agent in New York: ‘Doubting as we do whether any of the other Contractors have made proper dispositions for a supply in the West Indies, we think it probable that the General may call upon us for more than one fourth part of his whole supply.’[27]

In the event, this would prove quite an underestimate. On 1 April, Howe and Loring concluded an agreement for Mure, Son & Atkinson to provide 350,000 gallons of rum. This colossal order – equivalent to one-sixth of the volume that would be exported from the West Indies to Britain that year – was the entire quantity required by the army for the year ahead.[28] (General Howe told John Robinson that he had thought it advisable to confine the order to Mure, Son & Atkinson, rather than divide it between several contractors, so that ‘there might be no disappointment in the main Object’.)[29] Unfortunately Howe and Loring chose not to specify the cost. Instead they declared: ‘Whereas the price of Rum is very fluctuating and it is impossible to obtain sufficient Information on that Head, it is agreed by & between the Partys that the same be referred as a Point hereafter to be settled upon the most reasonable Terms between the right Honourable the Lords Commissioners of his Majesty’s Treasury and the said Messrs Mure Son & Atkinson.’[30]

The Lords of the Treasury heard about the new contract in early June, shortly after Lord North’s humiliating budget speech, and they soon told Howe that they were unable to ‘ascertain here the price to be paid for Rum’, instead ordering him to settle the matter from New York.[31] Unsurprisingly, Richard saw things differently; he believed a clear understanding had existed that any top-up order from America needed only to specify the quantity of rum, since the price had already been fixed at the time of the previous contract in May 1776.

The Lords of the Treasury would spend many hours considering the rum contracts over the summer of 1777, and Richard would be repeatedly summoned to appear before them. On 10 July they ordered him to cut his agency rate from 2½ to 1½ per cent, an indignity to which he ‘chearfully’ submitted, while voicing concerns that his rival merchants might see this as a scheme of his own devising to undercut them. ‘These things are not reckoned reputable in the City,’ he told John Robinson.[32]

Sometime in mid-July, Beeston Long and the other referees filed their report on Richard’s previous rum contract, the one from May 1776. They concluded that the spirit had been too expensive at 5s 3d per gallon, and proposed it should be priced at 4s ¾d – a reduction of nearly a quarter. Richard disputed this figure on grounds that they had incorrectly estimated the cost of the insurance premium at 13½ per cent – despite having seen the actual policies, which showed that of the 1,126 puncheons of rum which Mure, Son & Atkinson had arranged to be shipped to America, the premium paid on 826 barrels had been 15 per cent of their value, and on 100 barrels it had been 25 per cent. On 200 barrels Richard had been unable to secure cover – too bad that this last consignment had been seized by privateers. According to Richard’s calculations, these costs and uninsured losses were equivalent to an insurance premium of 31½ per cent – which proved that, far from having profited by the contract, as was claimed, he had lost by it.

After the referees refused to concede that he might have a point, Richard’s tone turned combative. On 23 July he wrote to the Treasury Board, hoping they would ‘consider the increased price of 5s. 6d. as the very lowest’ fair price for the rum.[33] By mid-August his patience was all but exhausted, and he wrote an exasperated letter to the Treasury, reeling off some of the unforeseeable events that ‘every Contractor not meaning to ruin himself’ was obliged to factor into his prices:

Short Crops in Jamaica. Combinations against him. Negligence of Agents. Misconduct of Masters of Ships. Want of supply of Lumber. Long Detention & consequent Leakage and Expences in following the army from Port to Port in America; but above all that imminent Danger inseparable from the nature of the Undertaking, by which so heavy a Loss has been actually sustained, the Danger of uninsurable Risques.[34]

It was a howl of frustration from a man whose considerable powers of persuasion seemed for once to have deserted him.

LIKE ALL CIVIL WARS, the conflict in America created fault lines that severed families and friendships; such was the rift between Benjamin Franklin and his loyalist son William, the last colonial governor of New Jersey, that they never made their peace. Suffice to say, Robert Erskine could not have foreseen that within five years of his arrival in New Jersey he would find himself on the opposite side of a full-blown war from his friend Richard Atkinson.

Before his move to the colonies, Erskine had been a surveyor of some repute. The first map he drew for George Washington, which charted adjoining districts of New Jersey and New York, was small enough to be folded in a pocket; Erskine handed it to the general himself. Shortly afterwards, on 19 July 1777, Washington wrote to Congress: ‘A good Geographer to Survey the roads and take sketches of the Country where the Army is to Act would be extremely useful and might be attended with exceeding valuable consequences.’[35] Which is how Erskine came to be appointed Surveyor General to the Continental Army, with the rank of colonel. However, his sense of obligation towards Richard and the other owners of the ironworks prevented him from taking up the position until he had made arrangements for his absence. ‘The great Confidence my employers have all along placed in my integrity and honour, has demanded my best endeavours on their behalf,’ Erskine explained to Washington. ‘What ever feuds and differences take place between States and nations yet these cannot alter the nature of justice between man & man; or cancel the duty, one individual owes to another.’[36] Despite the political chasm dividing him from the men who had sent him to America in the first place, his loyalty towards them did not falter.

During the next three years, Erskine and his team of assistant surveyors, draughtsmen and chain-bearers traversed New Jersey, New York, Connecticut and Pennsylvania, creating more than 250 maps that would prove of inestimable value to the revolutionary cause. He would never meet Richard Atkinson again; for a heavy cold contracted in the field soon turned into a fever, and he died at Ringwood on 2 October 1780. Less than two years later, the New Jersey legislature would pass an act confiscating the ironworks from its British proprietors and vesting control in Erskine’s widow and her second husband.[37]

ALTHOUGH THE FRENCH loudly protested their neutrality, it was an open secret that they were providing all manner of supplies to the American rebels – cannons, rifles, gunpowder, clothes, leather, salt, brandy and wine. American privateers, meanwhile, were welcomed at French ports. ‘I trust the different Vessels that hover round the Island will be put on their guard particularly to protect Liverpool, Whitehaven, the Clyde and even Bristol,’ the king wrote to John Robinson in May 1777, ‘for I do suspect that the Rebel vessels which have been assembling at Nantes and Bordeaux mean some stroke of that kind which will undoubtedly occasion much discontent among the Merchants.’[38]

Sure enough, in August, at the mouth of the English Channel, American privateers managed to pick off two ships from a 160-strong merchant convoy returning from Jamaica, and sailed them to Nantes, where they were plundered, stripped of their rigging and abandoned on mud flats. One of the vessels, the Hanover Planter, which belonged to Mure, Son & Atkinson, had 360 hogsheads of sugar and eighty-seven puncheons of rum on board. Lord Stormont, the British ambassador to France, personally negotiated the return of the ships and their valuable cargoes, an outcome which prompted Lord North to write, on 25 September, that he was ‘more sanguine’ than he had been for a while in his ‘expectations of the continuance of peace’.[39]

The main thrust of the British campaign in America for 1777 was to isolate the rebellious New England colonies from the more loyalist middle colonies by securing the Hudson River; General Burgoyne would lead a southbound expedition from Montreal, with General Howe leading a northbound one from New York, and the two forces would converge on Albany. ‘Gentleman Johnny’ Burgoyne’s push started well, with the capture of Fort Ticonderoga on 6 July. Howe changed his mind, however, and instead sent his army south to take Philadelphia. An inveterate gambler, Burgoyne chose to press ahead, but his luck ran out at Saratoga on 17 October; surrounded by the Continental Army, he was forced to surrender with nearly six thousand men. The defeat would prove a turning point of the war, for it persuaded the French that it might be worth openly backing the American cause. ‘This unhappy Event,’ Lord Stormont reported from Paris, ‘has greatly elevated all our secret Enemies here, and they break out, tho’ not in my Presence into the most intemperate Joy.’[40]

RICHARD’S RUM CONTRACTS would go down as a footnote in the history of the American war, yet they consumed an undue quantity of ministerial time, and generated a mind-numbing amount of paperwork. I could well imagine how all those beleaguered clerks must have felt; after weeks spent sifting through hundreds of Treasury and Colonial Office box files and letterbook volumes in the bunker-like confines of the National Archives at Kew, I myself felt heartily sick of the business.

A letter in which General Howe refused to suggest a price for the rum reached Whitehall from Philadelphia in January 1778; he merely expressed his regret that the affairs of Mure, Son & Atkinson, who had ‘exerted themselves so manifestly upon every occasion which has fallen under my Observation’, should have been left undetermined for so long ‘from a Chain of Difficultys they could not foresee’.[41] Richard continued to press the Treasury Board for a decision. The ‘unexampled Hardship’ of his case, he argued on 12 January, had only worsened in recent months – of the 4,032 puncheons of rum shipped by Mure, Son & Atkinson in fulfilment of the April 1777 agreement, 1,490 barrels had been lost to American privateers.[42]

The Lords of the Treasury again summoned Richard before them on 22 January, and informed him that they wished to turn the last rum contract retrospectively into an agency agreement, and for Mure, Son & Atkinson to bill them for the various costs of fulfilling it, plus the usual 1½ per cent commission. However, Richard rejected their proposal as completely unworkable:

Your Lordships know that we offered originally to transact this branch of business on a commission if it had been thought fit. But when your Lordships very properly determined that so distant a service was not fit to be carried on otherwise than upon contract, we considered ourselves as accountable to no body for our proceedings & executed what we had undertaken in a way so entirely interwoven with our other affairs in Jamaica & concerns of shipping: that they cannot now be separated.[43]

When Richard learnt, two days later, that the Treasury Board still planned to convert this contract into an agency, despite his objections, he wrote again: ‘I have already in so many ways submitted to you the Impossibility of stating the Expences as an Account, that I am at a Loss how to assert that Impossibility in Terms more decisive.’ So sure did he remain of his position that he offered to hand over the arbitration of the rum contracts to another ‘indifferently chosen’ referee, and the decision was soon entrusted to Stephen Fuller, the Jamaican Assembly’s agent in Britain.[44]

By now, Richard’s role as the government’s shipping agent had started to attract hostile attention. A letter in the Public Ledger, published on 17 December 1777, made the scandalous claim that Richard paid a £5,000 salary to his friend John Robinson, Secretary to the Treasury, which he funded by overcharging for the shipping that he chartered on the Treasury’s behalf. This could not go unchallenged, and a jury found in Richard’s favour, judging the article to be ‘grossly libellous’, since it falsely accused him of ‘imposing on his employer, and bribing a person to avoid detection’.[45]

Some mud must have stuck, nonetheless, since shortly afterwards, in the House of Lords, the Earl of Effingham tabled motions to obtain ‘more accurate accounts from the Treasury of the ships taken up by them for the service of America’.[46] On 12 March 1778, before a committee of the House, Richard endured lengthy interrogation about the transport service. When the Duke of Richmond enquired what he charged for his agency, Richard explained that he had originally received the standard merchant’s commission of 2½ per cent, until the Treasury Board docked it by a point. Lord Shelburne wondered whether Richard thought the Treasury ‘had been too hard upon him’, to which he replied that ‘he must say he seriously did’ (a response which apparently ‘set the House a laughing heartily’). Lord Effingham invoked parliamentary privilege, which protected him against defamation charges, for what he had to say on the subject: ‘These premises fully authorised him to brand this transaction with its true name, a job; and that of the most disgraceful nature. It carried about it all its proper marks; it was a most beneficial contract, made in the dark, with a favourite contractor.’[47] The word ‘job’ was often used during the eighteenth century in connection with grasping corruption – Dr Johnson’s dictionary definition was ‘a low mean lucrative busy affair’.[48]

This discussion was merely the curtain-raiser for a heated debate in the lower house, on 23 March, in which Colonel Barré tabled a motion for a select committee to investigate the money squandered on the ‘disgraceful, ruinous, and inglorious’ war.[49] The motion was passed, whereupon the committee of twenty-one MPs decided to focus on the rum business – and specifically on Richard’s first contract, whose terms had been so hastily agreed with Lord North back in September 1775. This particular transaction had not come under the referees’ scrutiny, but now, over the following weeks, more than two dozen witnesses – under-secretaries, chief clerks, insurance brokers, sugar brokers, planters and merchants among them – were called upon to analyse its every last detail.