Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 17, No. 102, June, 1876

A pleasant excursion is to take a little steamer, which runs up the Bosphorus and back, touching at Beicos (Bey Kos), and visit the Giant Mountain, from which is a magnificent view of the Black Sea and nearly the whole length of the Bosphorus. We breakfasted early, but when ready to start found our guide had disappointed us, and his place was not to be supplied. The day was perfect, and rather than give up our trip we determined to go by ourselves, trusting that the success which had attended similar expeditions without a commissionnaire would not desert us on this occasion. The sail up on the steamer was charming. There are many villages on the shores of the Bosphorus, and between them are scattered palaces and summer residences, the latter often reminding us of Venetian houses, built directly on the shore with steps down to the water, and caïques moored at the doors, as the gondolas are in Venice. The houses are surrounded by beautiful gardens, with a profusion of flowers blooming on the very edge of the shore, their gay colors reflected in the waves beneath.

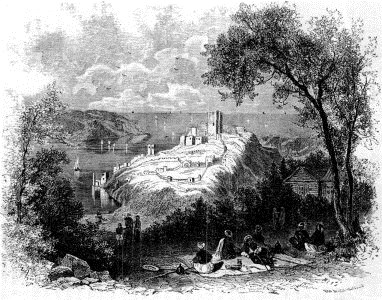

We learned from the captain of the steamer that Giant Mountain was two and a half miles from the village, with no very well-defined road leading to it; so on landing at Bey Kos we made inquiries for a guide, and this time were successful. Horses were also forthcoming, but no side-saddle. I respectfully declined to follow the example of my Turkish sisters and mount a gentleman's saddle; neither was I anxious to ride my Arab steed bareback, so we concluded to try a cow-carriage, and despatched our guide to hire the only one the place afforded. This stylish establishment was not to be had; so, having wasted half an hour in trying to find some conveyance, we gave it up and started on foot; and were glad afterward that we did so. The road was shaded to the base of the mountain, and led through a beautiful valley, the fields covered with wild-flowers. I have never seen such masses of color—an acre perhaps of bright yellow, perfectly dazzling in the sunlight, then as large a mass of purple, next to that an immense patch of white daisies, so thick they looked like snow. The effect of these gay masses, with intervals of green grass and grain, was very gorgeous. We passed two of the sultan's palaces, one built in Swiss style. The ascent of Giant Mountain from the inland side is gradual, while it descends very abruptly on the water-side. On the top of the mountain are the ruins of the church of St. Pantaleon, built by Justinian, also a mosque and the tomb of Joshua: so the Turks affirm. From a rocky platform just below the mosque there is a magnificent view. Toward the north you look off on the Black Sea and the old fortress of Riva, which commands the entrance to the Bosphorus. In front and to the south winds the beautiful Bosphorus for sixteen miles till it reaches the Sea of Marmora, which you see far in the distance glittering in the sunlight. You look down on the decks of the passing vessels, and the large steamers seem like toy boats as they pass below you. Near the mosque is a remarkable well of cool water. Shrubs and a few small trees grow on the mountain, and the ground is covered with quantities of heather, wild-flowers and ivy. We picked long spikes of white heather in full bloom, and pansies, polyanthus, the blue iris and many others of our garden flowers. The country all around Constantinople is very destitute of trees. The woods were cut down long ago, and the multitudes of sheep, which you see in large flocks everywhere, crop the young sprouts so they cannot grow up again.

FORTRESS OF RIVA, AND THE BLACK SEA.

Returning to Constantinople, our steamer ran close to the European shore, stopping at the villages on that side. Most of the officers of these boats are Turks, but they find it necessary to employ European (generally English) engineers, as the Turks are fatalists and not reliable. It is said they pay but little attention to their machinery and boilers, reasoning that if it is the will of Allah that the boiler blow up, it will certainly do so; if not, all will go right, and why trouble one's self? Laughable stories are told of the Turkish navy; e.g., that a certain captain was ordered to take his vessel to Crete, and after cruising about some time returned, not being able to find the island. Another captain stopped an English vessel one fine day to ask where he was, as he had lost his reckoning, although the weather had been perfectly clear for some time. In the Golden Horn lies an old four-decker which during the Crimean war was run broadside under a formidable battery by her awkward crew, who were unable to manage her, and began in their fright to jump overboard. A French tugboat went to the rescue and towed her off.

On our way to the hotel we saw the sultan's son, a boy of fifteen. He was driving in a fine open carriage drawn by a very handsome span of bay horses, and preceded by four outriders mounted on fine Arabian horses. Coachman, footman and outriders, in the black livery of the sultan, were resplendent in gold lace. The harness was of red leather and the carriage painted of the same bright color. The cushions were of white silk embroidered with scarlet flowers. It was a dashing equipage, but seemed better suited to a harem beauty than the dark, Jewish-looking boy in the awkward uniform of a Turkish general who was its sole occupant.

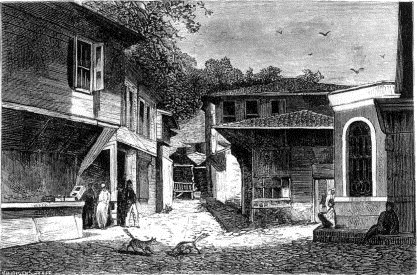

TURKISH QUARTER—STAMBOUL.

Yesterday we took our last stroll in Constantinople, crossing the Golden Horn by the new bridge to Stamboul. This bridge is a busy spot, for besides the constant throngs that cross and recross, it is the favorite resort of beggars and dealers in small wares. Many of the ferryboats also start from here, so that, although long and wide, it is crowded most of the day. An Englishman who is an officer in the Turkish army told us of an amusing adventure of his in crossing the bridge. He had been at the war department, and was told he could have the six months' pay which was due him if he would take it in piasters. Thankful to get it, and fearing if he did not take it then in that shape he might have to wait a good while, he accepted, and the piasters (which are large copper coins worth about four cents of our money) were placed in bags on the backs of porters to be taken to a European bank at Pera. As they were crossing the bridge one of the bags burst open with the weight of the coins, and a quantity of them were scattered. Of course a first class scramble ensued, in which the beggars, who are always on hand, and others reaped quite a harvest, and when the officer got the hole tied up the ammale found the bag considerably lighter to carry.

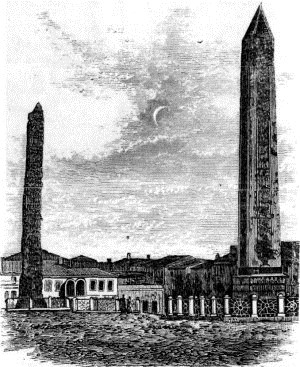

Reaching Stamboul, we made our way through the crowded streets, past the Seraglio gardens and St. Sophia, till we reached the old Hippodrome, which was modeled after the Circus at Rome. Little remains of its ancient glory, for the Crusaders carried off most of its works of art. The granite obelisk of Theodosius and the pillar of Constantine, which the vandal Turks stripped of its bronze when they first captured the city, are still left, but the stones are continually falling, and it will soon be a ruin. The serpentine column consists of three serpents twisted together: the heads are gone, Mohammed II. having knocked off one with his battle-axe. A little Turk was taking his riding-lesson on the level ground of the Hippodrome, and his frisky little black pony gave the old fellow in attendance plenty of occupation. We watched the boy for a while, and then, passing on toward the Marmora, took a look at the "Cistern of the Thousand Columns." A broad flight of steps leads down to it, and the many tall slender columns of Byzantine architecture make a perfect wilderness of pillars. Wherever we stood, we seemed always the centre from which long aisles of columns radiated till they lost themselves in the darkness. The cistern has long been empty, and is used as a ropewalk.

The great fire swept a large district of the city here, which has been but little rebuilt, and the view of the Marmora is very fine. On the opposite Asiatic shore Mount Olympus, with its snow-crowned summit, fades away into the blue of the heavens. This is a glorious atmosphere, at least at this season, the air clear and bracing, the sky a beautiful blue and the sunsets golden. In winter it is cold, muddy and cheerless, and in midsummer the simoom which sweeps up the Marmora from Africa and the Syrian coast renders it very unhealthy for Europeans to remain in the city. The simoom is exceedingly enervating in its effects, and all who can spend the summer months on the upper Bosphorus, where the prevailing winds are from the Black Sea and the air is cool and healthful. Nearly all the foreign legations except our own have summer residences there and beautiful grounds.

OBELISK OF THEODOSIUS.

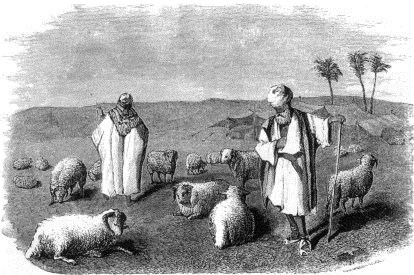

Following the old aqueduct built by the emperor Hadrian, which still supplies Stamboul with water, and is exceedingly picturesque with its high dripping arches covered with luxuriant ivy, we reached the walls which protected the city on the land-side, and then, threading our way through the narrow, dirty streets, we returned to the Golden Horn. I do not wonder, after what I have seen of this part of Stamboul, that the cholera made such ravages here a few years since. I should think it would remain a constant scourge. Calling a caïque, we were rowed up the Golden Horn to the Sweet Waters, but its tide floated only our own boat, and the banks lacked the attraction of the gay groups which render the place so lively on Fridays. We were served with coffee by a Turk who with his little brasier of coals was waiting under a wide-spreading tree for any chance visitor, and after a short stroll on the bank opposite the sultan's pretty palace we floated gently down the stream till we reached the Golden Horn again. On a large meadow near the mouth of the Sweet Waters some Arabs were camped with an immense flock of sheep. They had brought them there to shear and wash the wool in the fresh water, and the ground was covered with large quantities of beautiful long fleece. The shepherds in their strange mantles and head-dresses looked very picturesque as they spread the wool and tended their flocks. Our caïquegee, as the oarsman of a caïque is called, ought not to be overlooked. His costume was in keeping with his pretty caïque, which was painted a delicate straw-color and had white linen cushions. He was a tall, finely-built fellow, a Cretan or Bulgarian I should think, for he looked too wide awake for a Turk. The sun had burned his olive complexion to the deepest brown, and his black eyes and white teeth when he smiled lighted up his intelligent face, making him very handsome. He wore a turban, loose shirt with hanging sleeves and voluminous trousers, all of snowy whiteness. A blue jacket embroidered with gilt braid was in readiness to put on when he stopped rowing. It must have taken a ruinous amount of material to make those trousers. They were full at the waist and knee, and before seating himself to his oars he gracefully threw the extra amount of the fullness which drooped behind over the wide seat as a lady spreads out her overskirt.

SHEPHERDS.

Last night we bade farewell to the strange old city with its picturesque sights, its glorious views and the many points of interest we had grown so familiar with. Our adieus were said, the ammales had taken our baggage to the steamer, which lay at anchor off Seraglio Point, and before dark we went on board, ready to sail at an early hour.

The bustle of getting underway at daylight this morning woke me, and I went on deck in time to take a farewell look. The first rays of the sun were just touching the top of the Galata Tower and lighting up the dark cypresses in the palace-grounds above us. The tall minarets and the blue waves of the Bosphorus caught the golden light, while around Olympus the rosy tint had not yet faded and the morning mists looked golden in the sunlight. We rounded Seraglio Point and steamed down the Marmora, passed the Seven Towers, and slowly the beautiful city faded from our view.

SHEILA HALE.THEE AND YOU

A STORY OF OLD PHILADELPHIA. IN TWO PARTS.—I

Once on a time I was leaning over a book of the costumes of forty years before, when a little lady said to me, "How ever could they have loved one another in such queer bonnets?" And now that since then long years have sped away, and the little critic is, alas! no longer young, haply her children, looking up at her picture by Sully in a turban and short waist; may have wondered to hear how in such disguise she too was fatal to many hearts, and set men by the ears, and was a toast at suppers in days when the waltz was coming in and the solemn grace of the minuet lingered in men's manners.

And so it is, that, calling up anew the soft September mornings of which I would draw a picture before they fade away, with me also, from men's minds, it is the quaintness of dress which first comes back to me, and I find myself wondering that in nankeen breeches and swallow-tailed blue coats with buttons of brass once lived men who, despite gnarled-rimmed beavers and much wealth of many-folded cravats, loved and were loved as well and earnestly as we.

I had been brought up in the austere quiet of a small New England town, where life was sad and manners grave, and when about eighteen served for a while in the portion of our army then acting in the North. The life of adventure dissatisfied me with my too quiet home, and when the war ended I was glad to accept the offer of an uncle in China to enter his business house. To prepare for this it was decided that I should spend six months with one of the great East India firms. For this purpose I came to Philadelphia, and by and by found myself a boarder in an up-town street, in a curious household ruled over by a lady of the better class of the people called Friends.

For many days I was a lonely man among the eight or ten people who came down one by one at early hours to our breakfast-table and ate somewhat silently and went their several ways. Mostly, we were clerks in the India houses which founded so many Philadelphia fortunes, but there were also two or three of whom we knew little, and who went and came as they liked.

It was a quiet lodging-house, where, because of being on the outskirts and away from the fashion and stir of the better streets, chiefly those came who could pay but little, and among them some of the luckless ones who are always to be found in such groups—stranded folks, who for the most part have lost hope in life. The quiet, pretty woman who kept the house was of an ancient Quaker stock which had come over long ago in a sombre Quaker Mayflower, and had by and by gone to decay, as the best of families will. When I first saw her and some of her inmates it was on a pleasant afternoon early in September, and I recall even now the simple and quiet picture of the little back parlor where I sat down among them as a new guest. I had been tranquilly greeted, and had slipped away into a corner behind a table, whence I looked out with some curiosity on the room and on the dwellers with whom my lot was to be cast for a long while to come. I was a youth shy with the shyness of my age, but, having had a share of rough, hardy life, ruddy of visage and full of that intense desire to know things and people that springs up quickly in those who have lived in country hamlets far from the stir and bustle of city life.

The room I looked upon was strange, the people strange. On the floor was India matting, red and white in little squares. A panel of painted white wood-work ran around an octagonal chamber, into which stole silently the evening twilight through open windows and across a long brick-walled garden-space full of roses and Virginia creepers and odorless wisterias. Between the windows sat a silent, somewhat stately female, dressed in gray silk, with a plain frilled cap about the face, and with long and rather slim arms tightly clad in silk. Her fingers played at hide-and-seek among some marvelous lace stitches—evidently a woman whose age had fallen heir to the deft ways of her youth. Over her against the wall hung a portrait of a girl of twenty, somewhat sober in dress, with what we should call a Martha Washington cap. It was a pleasant face, unstirred by any touch of fate, with calm blue eyes awaiting the future.

The hostess saw, I fancied, my set gaze, and rising came toward me as if minded to put at ease the new-comer. "Thee does not know our friends?" she said. "Let me make thee known to them."

I rose quickly and said, "I shall be most glad."

We went over toward the dame between the windows. "Mother," she said, raising her voice, "this is our new friend, Henry Shelburne, from New England."

As she spoke I saw the old lady stir and move, and after a moment she said, "Has he a four-leaved clover?"

"Always that is what she says. Thee will get used to it in time."

"We all do," said a voice at my elbow; and turning I saw a man of about thirty years, dressed in the plainest-cut Quaker clothes, but with a contradiction to every tenet of Fox written on his face, where a brow of gravity for ever read the riot act to eyes that twinkled with ill-repressed mirth. When I came to know him well, and saw the preternatural calm of his too quiet lips, I used to imagine that unseen little demons of ready laughter were for ever twitching at their corners.

"Mother is very old," said my hostess.

"Awfully old," said my male friend, whose name proved to be Richard Wholesome.

"Thee might think it sad to see one whose whole language has come to be just these words, but sometimes she will be glad and say, 'Has thee a four-leaved clover?' and sometimes she will be ready to cry, and will say only the same words. But if thee were to say, 'Have a cup of coffee?' she would but answer, 'Has thee a four-leaved clover?' Does it not seem strange to thee, and sad? We are used to it, as it might be—quite used to it. And that above her is her picture as a girl."

"Saves her a deal of talking," said Mr. Wholesome, "and thinking. Any words would serve her as well. Might have said, 'Topsail halyards,' all the same."

"Richard!" said Mistress White. Mistress Priscilla White was her name.

"Perchance thee would pardon me," said Mr. Wholesome.

"I wonder," said a third voice in the window, "does the nice old dame know what color has the clover? and does she remember fields of clover—pink among the green?"

"Has thee a four-leaved clover?" re-echoed the voice feebly from between the windows.

The man who was curious as to the dame's remembrances was a small stout person whose arms and legs did not seem to belong to him, and whose face was strangely gnarled, like the odd face a boy might carve on a hickory-nut, but withal a visage pleasant and ruddy.

"That," said Mistress White as he moved away, "is Mr. Schmidt—an old boarder with some odd ways of his own which we mostly forgive. A good man if it were not for his pipe," she added demurely—"altogether a good man."

"With or without his pipe," said Mr. Wholesome.

"Richard!" returned our hostess, with a half smile.

"Without his pipe," he added; and the unseen demons twitched at the corners of his mouth anew.

Altogether, these seemed to me droll people, they said so little, and, saving the small German, were so serenely grave. I suppose that first evening must have made a deep mark on my memory, for to this day I recall it with the clearness of a picture still before my eyes. Between the windows sat the old dame with hands quiet on her lap now that the twilight had grown deeper—a silent, gray Quaker sphinx, with one only remembrance out of all her seventy years of life. In the open window sat as in a frame the daughter, a woman of some twenty-five years, rosy yet as only a Quakeress can be when rebel Nature flaunts on the soft cheek the colors its owner may not wear on her gray dress. The outline was of a face clearly cut and noble, as if copied from a Greek gem—a face filled with a look of constant patience too great perhaps for one woman's share, with a certain weariness in it also at times, yet cheerful too, and even almost merry at times—the face of one more thoughtful of others than herself, and, despite toil and sordid cares, a gentlewoman, as was plain to see. The shaft of light from the window in which she sat broadened into the room, and faded to shadow in far corners among chairs with claw toes and shining mahogany tables—the furniture of that day, with a certain flavor about it of elegance, reflecting the primness and solidness of the owners. I wonder if to-day our furniture represents us too in any wise? At least it will not through the generations to follow us: of that we may be sure. In the little garden, with red graveled walks between rows of box, walked to and fro Mr. Schmidt, smoking his meerschaum—a rare sight in those days, and almost enough to ensure your being known as odd. He walked about ten paces, and went and came on the same path, while on the wall above a large gray cat followed his motions to and fro, as if having some personal interest in his movements. Against an apricot tree leaned Mr. Wholesome, watching with gleams of amusement the cat and the man, and now and then filliping at her a bit of plaster which he pulled from the wall. Then the cat would start up alert, and the man's face would get to be quizzically unconscious; after which the cat would settle down and the game begin anew. By and by I was struck with the broad shoulders and easy way in which Wholesome carried his head, and the idea came to me that he had more strength than was needed by a member of the Society of Friends, or than could well have been acquired with no greater exercise of the limbs than is sanctioned by its usages. In the garden were also three elderly men, all of them quiet and clerkly, who sat on and about the steps of the other window and chatted of the India ships and cargoes, their talk having a flavor of the spices of Borneo and of well-sunned madeira. These were servants of the great India houses when commerce had its nobles and lines were sharply drawn in social life.

I was early in bed, and rising betimes went down to breakfast, which was a brief meal, this being, as Mr. Wholesome said to me, the short end of the day. I should here explain that Mr. Wholesome was a junior partner in the house in which I was to learn the business before going to China. Thus he was the greatest person by far in our little household, although on this he did not presume, but seemed to me greatly moved toward jest and merriment, and to sway to and fro between gayety and sadness, or at the least gravity, but more toward the latter when Mistress White was near, she seeming always to be a checking conscience to his mirth.

On this morning, as often after, he desired me to walk with him to our place of business, of which I was most glad, as I felt shy and lonely. Walking down Arch street, I was amazed at its cleanliness, and surprised at the many trees and the unfamiliar figures in Quaker dresses walking leisurely. But what seemed to me most curious of all were the plain square meeting-houses of the Friends, looking like the toy houses of children. I was more painfully impressed by the appearance of the graves, one so like another, without mark or number, or anything in the disposition of them to indicate the strength of those ties of kinship and affection which death had severed. Yet I grew to like this quiet highway, and when years after I was in Amsterdam the resemblance of its streets to those of the Friends here at home overcame me with a crowd of swift-rushing memories. As I walked down of a morning to my work, I often stopped as I crossed Fifth street to admire the arch of lindens that barred the view to the westward, or to gaze at the inscription on the 'Prentices' Library, still plain to see, telling that the building was erected in the eighth year of the Empire.

One morning Wholesome and I found open the iron grating of Christ Church graveyard, and passing through its wall of red and black glazed brick, he turned sharply to the right, and coming to a corner bade me look down where under a gray plain slab of worn stone rests the body of the greatest man, as I have ever thought, whom we have been able to claim as ours. Now a bit of the wall is gone, and through a railing the busy or idle or curious, as they go by, may look in and see the spot without entering.