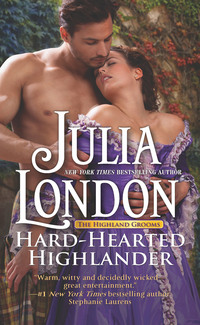

The Highland Grooms

She didn’t understand why he was telling her and looked curiously at him.

His gray brows floated upward. “Well? Make note, make note!” he demanded, and walked on.

But she had nothing with which to make a note.

She followed his lordship, and in the next room, he pointed out more things that, presumably, she was to make a note of, uncaring that she had nothing with which to write his wishes, and apparently expecting her to commit it all to memory.

When he’d toured the house he said, “MacDonald has assured me the furnishings will arrive this afternoon. Go, go, now, busy yourselves,” he said, waving his hands at the ladies in a sweeping motion. “Where is my brother? Has the second coach not come along?” He marched out of the room.

Bernadette waited until she was certain he was gone before looking back at Lady Kent and Avaline. “So much to do,” she said, smiling a little. “At least we’ll have something to occupy us.”

Neither Kent woman looked convinced of that.

The furniture did indeed arrive that afternoon, on a caravan of carts and wagons. The servants who had the misfortune of being dragged to Scotland scampered about, with the Kent butler, Renard, directing things to be placed here and there. It quickly became apparent that even with all they’d brought, filling the hold in the Mackenzie ship with beds and cupboards and settees, there was not enough to furnish this large house. Three bedrooms sat empty, as well as a sitting and a morning room.

In the evening, before a cold meal was to be served, Lord Kent called Bernadette to him in the library. Its shelves still sported some of the books of the previous owners. There was no sign of muskets in this room.

“Make a list of all we need, then send it to Balhaire,” he said without greeting.

“Yes, my lord. To someone’s attention in particular?”

“Naturally, to someone’s attention. The laird there.” He perched one hip on the desk and folded his arms across his chest. “Now, listen to me, Bernadette. You’ll have to do the thinking for Avaline.”

“Pardon? I don’t—”

“She’s a child,” he said bluntly. “She can’t possibly run a house this large, and her mother has been an utterly incompetent teacher.” He leaned forward, reached for a bottle and poured brandy into a glass. “You need to prepare her for this marriage.”

Bernadette swayed backward. “I can’t take the place of her mother.”

“You’ve been doing it these last few years,” he said. “And you have experience in this...inexperience,” he said, flicking his wrist at her. “I doubt her mother can recall a blessed thing about her wedding night.”

Bernadette’s face began to warm. She was very uncomfortable with the directions of this conversation.

“Come now, I don’t say it to demean you,” he said impatiently, trying to read her thoughts. “I say it to point out that you know more than you think. Teach her how to present herself to her husband. Teach her how to please a man.” He tossed the brandy down his throat.

“My lord!” Bernadette protested.

“Don’t grow missish on me,” he snapped. “She must please him, Bernadette. Do you understand me? As much as I am loath to admit it, I need those bloody Mackenzies to look after my property here. I want to expand my holdings, and I want access to the sea. Why should they have all the trade? If I fail to have them fully on board with me, I will not make these gains in a pleasant way, do you understand me? I am trusting you to ensure that little lamb knows to open her legs and do her duty.”

Bernadette gasped.

He clucked his tongue at her. “Don’t pretend you are a tender virgin. It was your own actions that put you in this position, was it not? You have benefited greatly from my employment of you when no one else would have you, and for that, you owe me your allegiance and your obedience. Do I need to say more?”

Bernadette couldn’t even speak. She thought herself beyond being shocked by anything that happened in the Kent household, but he had shocked her.

“Good. Now go and make sure her mother hasn’t frightened her half to death. And send Renard to me—surely we’ve brought some decent wine.”

Bernadette nodded again, fearing that if she spoke, she would say something to put her position in serious jeopardy. She was shaking with indignation as she walked out of the library.

It had been eight years since she and Albert Whitman had eloped, but sometimes it felt as if it was yesterday. So desperately in love, so determined to be free of her father’s rules for her. They’d managed nearly a week of blissful union, had made it to Gretna Green, had married. They were on their way to his parents’ home when her father’s men found them and dragged the two of them back to Highfield.

Bernadette had mistakenly believed that as she and Albert had legally married, and had lain together as husband and wife, that there was nothing her father could do. Oh, how she’d underestimated him—the marriage was quickly annulled, and Albert was quickly impressed onto a merchant ship. There was no hope for him—he was not a seaman, and was, either by accident or design, lost at sea several months later.

She had learned a bitter, heart-rending lesson—a father would go to great lengths to undo something his daughter had done against his express wishes. A vicar could be bribed or threatened to annul a marriage. Men could be paid to impress a young man in his prime and put him on a ship bound for India. A woman could watch her reputation and good name be utterly destroyed by her own actions, and a father’s invisible shackles could tighten around her even more.

After that spectacular fall from grace, everyone in and around Highfield knew what had happened. No one would even look at her on the street. Her friends fell away, and even her own sister had avoided her for fear of guilt by association.

No one seemed to know about the baby she’d lost, however. No, that was her family’s secret. Her father would have sooner died than have anyone know his daughter had carried a child of that union.

“Bernadette! There you are.”

She hadn’t seen Avaline, who appeared almost from air and grabbed her hand. “I don’t like it here,” she whispered as she glanced over her shoulder at Mr. MacDonald, who was standing in the entry. “There is nothing here, nothing nearby.”

“I’m sure there is,” Bernadette said. “I beg your pardon, Mr. MacDonald, but there is a village nearby, is there not?”

“No’ any longer,” he said.

“Not any longer? What does that mean, precisely?”

“I mean to say the English forces...” He paused. “Removed it.”

Removed it. “Ah...thank you, sir.” Bernadette glanced at Avaline. “It’s all right, darling—Balhaire is very near. Come and help me remember the things your father wants done, will you?” she asked, and pulled Avaline into a sitting room. Lady Kent was within, staring out the window, her arms wrapped tightly about her.

“What things?” Avaline asked.

“Pardon?” Lady Kent asked, turning about.

“I was reminding Avaline that there were several things his lordship wanted done, and asked that she help me remember them all,” Bernadette responded. “We must make this place pleasing for your fiancé,” she said to Avaline.

“Don’t call him that,” Avaline said.

“But that’s what he is. The betrothal has been made.”

“I don’t want the betrothal!” Avaline said, jerking her hand free of Bernadette’s. “He is ghastly.”

She was a petulant child, only a moment away from stomping her foot. “That’s enough, Avaline!” Bernadette said sternly. “Enough.”

Lady Kent gaped at Bernadette, shocked by her tone.

Bernadette groaned. “I beg your pardon, but you both know as well as I that there is nothing to be done for this engagement.”

Mother and daughter exchanged a look.

“This is what you were born to,” Bernadette said to Avaline. “To make your father rich and prosperous by furthering his connections. You can’t pretend it isn’t so or believe that petulance will change it.”

Avaline began to cry. So did her mother. They were like two kittens, mewling over spilled milk.

“For God’s sake, will you stop?” Bernadette pleaded. “Best you meet your fate head-on than like a tiny little hare afraid of her own shadow. He will respect you more if you don’t cower.”

“Oh dear,” Lady Kent said. “She’s right, darling.”

That surprised Bernadette. She watched as Lady Kent shakily swept the tears from her cheeks. “She’s quite right, really. I’ve cowered all my life and you know very well what that has gained me. If you are to make this marriage bearable, you must find your footing.”

Avaline’s eyes widened with surprise at this unexpected bit of advice from her mother. “But how?” she asked plaintively. “What am I to do?”

Lady Kent and her daughter both looked to Bernadette for the answer to that.

Good Lord, they were the two most hapless women she had ever known. Bernadette sighed. “You must prepare to meet him a second time and make him welcome. We’ll start there.”

Avaline nodded obediently.

Bernadette smiled encouragingly, but privately, she could think of nothing worse than having to meet that cold-hearted man a second time and pretend to welcome him. She’d known men like him, men who thought themselves so superior that civility was not necessary. Her first instinct had been visceral, and her humor when he was near quite deplorable. She would give a special thanks to heaven tonight that she was not the one who would have to spend the rest of her days in misery with him.

Poor Avaline.

CHAPTER FOUR

HE FIRST NOTICES her at the Mackenzie feill, an annual rite of celebration where Mackenzies and friends come from far and wide for games, dancing and song. She is wearing an arasaid plaid that leaves her ankles bare, and a stiom, the ribbon around her head that denotes she is not married. She is dancing with her friends, holding her skirt out and turning this way and that, kicking her heels and rising up on her toes and down again. She is laughing, her expression one of pure joy, and Rabbie feels a tiny tug in his heart that he’s never felt before. The lass intrigues him.

He moves, wanting to be closer. He catches her eye, and she smiles prettily at him, and that alone compels him to walk up to her and offer his hand.

She looks at his hand, then at him. “Do you mean to dance, then?”

He nods, curiously incapable of speech in that moment. Her soft brown eyes mesmerize him, make him think of the color of the hills in the morning light.

“Then you must ask, Mackenzie,” she teases him.

“W-will you dance, then?”

She laughs at his stammering and slips her hand into his. “Aye, lad. I will.”

They dance...all night. And for the first time in his twenty-seven years, Rabbie thinks seriously of marriage.

* * *

RABBIE’S MOTHER PUT her foot down with him, as if he was a lad instead of a man in his thirty-fifth year. As if he was still swaddled. “You will go and pay her a call,” she said firmly, her eyes blazing with irritation.

“She will no’ care if I call or no’,” he said dismissively.

“I care,” she snapped. “That you are not attached to her, that you do not care for her, is no excuse for poor manners. She is your fiancée now and you will treat her with the respect she is due.”

Rabbie laughed at that. “What respect is she due, Maither? She is seventeen, scarcely out of the nursery. She is a Sassenach.” She was pale and docile and hadn’t lived, not like he had. She had no experience beyond her own English parlor. She trembled when he was near—or when anyone was near, for that matter. He couldn’t imagine what he would even say to the lass, much less how he might inhabit the same house as her.

His mother sighed wearily at his pessimism. She sat next to him on the settee, where Rabbie had dropped like a naughty child when he’d been summoned. She put her hand on his knee and said, “My darling son, I’m so very sorry about Seona—”

Rabbie instantly vaulted to his feet. “Donna say her name.”

“I will say it. She’s gone, Rabbie. You can’t live your life waiting for a ghost.”

He shot his mother a warning look. “You think I wait for Seona to appear by sorcery? I saw her house. I saw where blood had spilled, where fires had burned,” he said, his gut clenching at the mere mention of it. “I’m no’ a dull man—I understand what happened. I’m no’ waiting for a ghost.” He strode to the window to avoid his mother’s gaze and to bite down his anger.

In his mind’s eye, he could see the house where Seona had lived with her family and a father who had abetted the Jacobites. A father who had sent his sons to join the forces marching to England to restore Charlie Stuart to the throne. They’d been slaughtered on the field at Culloden, and her father was hanged from an old tree on the shores of Lochcarron, so that any Highlander gliding past on a boat could see him, could see what vengeance the English had wrought on those who took Prince Charlie’s cause.

But Seona? Her sister, her mother? No one knew what had become of them. Their home had been ransacked, the servants gone, the livestock stolen or shot. There was no one left, no one who could say what had happened to them. The only ones to survive the carnage were Seona’s niece and nephew; two wee bairns who’d been sent to stay with a clan member when the news came the English were sweeping through the Highlands. There was no one else, no other MacBee living in these hills any longer. And judging by the devastation done to the MacBee home, a man could only imagine the worst—every night, in his dreams, he imagined it.

“If you’re not waiting for a ghost, then what are you waiting for?” his mother persisted as Rabbie tried once again to erase the image of the forsaken household.

Death. Every day, he waited for it. Perhaps in death he’d know what had become of the woman he’d loved. In death, there would be relief from this useless life he was living. From the searing guilt he bore every single day for having been unable to save her.

“And while you wait for whatever it is that will ease you, that poor English girl has been bartered like a fine ewe and has come all this way to a strange land, to marry a man she scarcely knows. A man who is older than her by more than fifteen years, and who is bigger than her in every way. Of course she is frightened. The least you might do is put her at ease.”

Rabbie slowly turned, fixing his gaze on his mother. “You are verra protective of a lass you scarcely know, are you no’?”

His mother’s vexation was apparent in the dip of her brows. “I was that lass once, Rabbie Mackenzie. I was a sheep, just like her, bartered to your father. I know what she must be enduring just now, and I have compassion for her. Just as I have compassion for you, darling—this isn’t what either of you hoped for, but it is what has come. If only you could find some compassion in your own heart for her, you might find a way to accept it.”

Rabbie didn’t know how to explain to his mother that words like compassion and hope were far beyond his capacity to fathom. He was merely existing, moving from one day to the next, contemplating his own death with alarming regularity.

His mother was accustomed to his surliness, however, and she didn’t wait for his answer, but turned and walked out the door of her sitting room, pausing just at the threshold. “Catriona will accompany you.”

“Cat!”

“Yes, Cat,” she said. “Your sister will be helpful in making Miss Kent feel comfortable and soothing any ruffled feathers.”

“Ruffled feathers,” he scoffed.

“Yes, Rabbie. Ruffled feathers. You have treated Miss Kent very ill.”

Rabbie shook his head.

“She’s a sweet girl. If you allowed yourself to stop thinking of your own hurts, you might be pleasantly surprised by her.”

Once again, his mother didn’t wait for him to say curtly that he couldn’t possibly be surprised by the likes of her, and quit the room.

Rabbie turned back to the window and stared blankly ahead. His mother’s words floated somewhere above him. His mind saw nothing but darkness.

* * *

WHEN RABBIE EMERGED in the bailey, having prepared himself as best he could to call on his fiancée, Catriona was already there, waiting impatiently for him. She was dressed properly, which was to say like a Sassenach. Highlanders were now banned by law from wearing plaid. His father had taken that edict to mean they should dress as the English would dress in all things. His father had softened with age, an old man with a bad leg who wanted no trouble from the redcoats that appeared from time to time at their door.

Catriona had a jaunty hat on her head, with a feather that shot off one side like an arrow’s quill. It was a hat that their sister-in-law, Daisy, had given Catriona when she and Cailean had come to Balhaire after brokering the marriage offer between the Mackenzies and the Kents.

Rabbie paused next to her mount and looked up at her hat. “That is ridiculous.”

“How verra kind,” she said saucily. “Should I inquire as to what has made you so bloody cross today, then?”

“The same that makes me cross every day—life,” he said, and hauled himself up onto the back of his horse. He gave his sister a sidelong glance. “I didna mean to wound your tender feelings,” he said, gesturing to her hat. “You know verra well what I meant by it, aye?”

“No, Rabbie, I donna know what you meant. I never know what you mean. No one knows what you mean anymore.” She was the second woman today to want no more words from him.

She wheeled her horse about and spurred it on, but then immediately drew up as two riders came in through the bailey gates. Seated behind each rider was a child.

“Who is it?” Rabbie asked as the riders turned to the right.

“You donna recognize them, then?” Catriona asked. Rabbie shook his head. “That is Fiona and Ualan MacLeod.”

The names were familiar to Rabbie, but it took him a moment to recall the children of Seona’s sister, Gavina MacBee MacLeod. The last he’d seen them they were bairns, Fiona having only learned to walk, and Ualan still toddling about on fat wee legs.

“Why are they here, then? Are they no’ in the care of a relative?”

Catriona looked at him. “Aye, the elderly cousin of a MacBee, I think. She’s passed.”

Rabbie’s gaze followed the riders with the children as they disappeared into the stables. “Who has them now?”

“No one,” Catriona said. “There are no MacBees or MacLeods left in these hills, are there? Aye, they’ve brought them to Balhaire for safe harbor until someone decides what’s to be done with them.”

Rabbie jerked his gaze to his sister. “Why was I no’ told of it?”

Catriona snorted. “Look at you, lad. Do you think any of us would add to your burden?” She sent her horse to a trot.

Rabbie looked back to where the riders had gone, but there was no sign of them. He reluctantly followed after Catriona.

The ride to Killeaven was quicker than by coach, which plodded along on old, seldom-used roads. Catriona and Rabbie rode through the forest on trails well known to them from having spent their childhood exploring the land around them. They splashed across a shallow river, then trotted up a glen, through a meadow. At the old Na Cùileagan cairn, they turned west and cantered across the open field where the Killeaven cattle and sheep had once grazed—but they were all gone, seized by the English and sold at market.

As they trotted into the drive—newly graveled—Rabbie noted the new windows and the repair to two chimneys. The weathered front door of the house swung open. Lord Kent, in the company of Lord Ramsey, strode out to greet them. Both men were dressed for riding. Behind them was Niall MacDonald. Slight and taciturn, he’d proven himself to be a keen observer. He was good at what he did for the Mackenzies—which consisted primarily of keeping his eyes and ears open and reporting back to the laird.

“There you are, Mackenzie,” Kent said. “I’d expected you well before now.”

His voice was slightly admonishing, and Rabbie resisted the urge to shrug. Not that Kent would have noticed—his gaze was on Catriona.

“I beg your pardon, we’ve been detained,” Rabbie lied. He swung off his horse to help down Catriona, but she’d leaped off her mount before he could reach her. “May I introduce my sister, Miss Catriona Mackenzie,” Rabbie said. “She was away when you arrived.”

“Miss Mackenzie,” Lord Kent said, bowing his head, and then introducing his brother. “Now then, Mackenzie. We would like to be about the business of stocking sheep here. We’ll need a market.”

“Glasgow,” Rabbie said instantly.

Kent frowned. “Glasgow is too far, isn’t it? I’d need drovers and such. I had in mind buying from Highlanders, such as yourself.”

Rabbie’s pulse quickened a beat or two. Kent thought he might help himself to what sheep they’d managed to keep, did he? “Our flocks have been decimated,” he said as evenly as he could. “Sheep and cattle alike.”

“We will eventually want to add cattle, naturally,” Kent said, as if Rabbie hadn’t spoken. If he understood how the Highland herds had been decimated, he was either unconcerned or obtuse. “But for now, we want to be about the business of sheep.”

Of course they did. Wool was a lucrative business.

“You have sheep there at Balhaire, do you not?” he asked, squinting curiously, as if he’d expected Rabbie to offer them up.

He might have said something foolish, but Catriona slipped her hand into the crook of his elbow and smiled sweetly at him. Her eyes, however, were full of warning. “Aye,” Rabbie said slowly. “But none for sale. They’ll be lambing soon.” That was a lie, but he gambled that Kent didn’t know one end of a sheep from the other.

“Well. Perhaps we’ll have a word with your father,” he said, exchanging a look with his brother. “We’re on our way to Balhaire now, as it happens.”

Rabbie could well imagine his father selling off half their flock so as not to “make trouble,” and said quickly, “You ought to call on the Buchanans” as casually as he might as he removed his gloves. “They’ve a flock they might cull.”

Behind Kent, Rabbie noticed the look of surprise on Niall’s face.

“The Buchanans,” Lord Kent repeated, sounding uncertain.

“Aye, the Buchanans. You’ll find them at Marraig, near the sea. Follow the road west. Mr. MacDonald knows where.”

Lord Kent looked back at his escort, whose expression had fallen back into stoicism, then at Rabbie. “How far?”

“Seven miles at most.”

“We’ll be met with hospitality, or a gun?”

Rabbie smiled. “This is the Highlands, my lord.” He let that statement linger, let Kent imagine what he would for a moment or two, and indeed, he and his brother exchanged another brief, but wary, look. “Aye, you’ll be met with hospitality, you will. But were I you, I’d have a man or two with me.”

Lord Kent nodded and gestured to his brother. “Assemble some of the men, then.”

He turned back to Rabbie. “Very well, we will call on the Buchanans. You’ll find your fiancée with the women.” He began striding for the stables, his business with Rabbie done.

Rabbie watched him go, trailed by his brother. Niall paused briefly before following them.

“Anything?” Rabbie asked in Gaelic.

“Only that the food is not to their liking,” Niall responded in kind.

“They’ll like it well enough, come winter,” Catriona said as she passed both men on her way to the door.

“The Buchanan sheep suffered the ovine plague,” Niall reminded Rabbie.

Rabbie gave Niall the closest thing to a smile he’d managed in weeks. “Aye, lad, that I know.”

“They’ve come round, they have,” Niall said.

“Who?”

“The Buchanans. I’ve seen them twice up on the hill behind Killeaven.”

“Aye, any clans remaining will come to have a look, will they no’?”

Niall shrugged. “It was odd, it was. They sit there, watching.”

There was no trust between the Buchanans and the Mackenzies. Rabbie couldn’t guess what they were about, but he’d reckon their interest wasn’t a neighborly one.