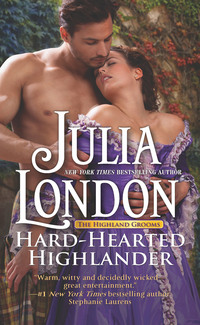

The Highland Grooms

Bernadette curtsied.

“Welcome, all,” Mrs. Vivienne Mackenzie said in a lovely, melodic voice. “There are more of us, aye? My husband has gone to bring our bairns to say good-night—” She hadn’t even finished her thought when five children burst into the room and raced for their mother and their grandparents. The oldest, a girl, looked to be thirteen or fourteen years old. And the youngest, a boy, perhaps eight years of age. The children were raucous and gay, and they caused Bernadette’s heart to squeeze painfully. Children, especially young children, always had that effect on her—they reminded her of her own loss. A loss so wretched that even after all these years, she could not escape its clutches at the most inopportune times. Even now, she felt flushed and had to look down at her feet to regain her balance.

The children were talking all at once, eager to be seen, eager to know their guests. Bernadette could well imagine that Lord Kent was nearly beside himself—he did not believe in mixing children with adults. She watched the children wiggle and sway about on their feet, unable to keep still. One boy carried something in his pocket that caused it to bulge, and Bernadette felt a smile softening her face. She would never know the pleasure of having a child that age. She would never feel the pride in watching one grow. When she’d lost her child, she’d almost died. She’d survived, but her ability to bear children had not.

When the children had received kisses from their family, Mrs. Mackenzie sent them out with a maid, and Bernadette happened to look up from them and realized with a start that Avaline’s fiancé was watching her. She felt as if she’d been caught in a private moment, and awkwardly rubbed her nape, unnerved at having been caught in the act of admiring children. She turned her back to him and walked to a small table in a corner, where she pretended to closely examine what she could only imagine were some sort of artifacts.

A moment later, his deep voice rumbled behind her. “I thought you fearless, yet here you stand, cowering in the corner.”

Ah, how lucky for her! The beast had followed her. Bernadette had managed to trap herself in the corner, and couldn’t escape him without causing a scene. His presence felt too large, too powerful, and she shifted closer to the wall. “I’m not cowering. I’m admiring these artifacts. What are they, some sort of ancient weapon?”

He leaned across her body, the arm of his coat brushing lightly against her bare forearm as he picked one up. He held it up to her. “This is a rock. One that my nephew has collected.”

Artifacts! She gave the rock a disapproving look as if it had deliberately misled her. Her cheeks bloomed with embarrassment. “I should have paid closer attention to my archeology lessons.” She wished he would move, step aside. He stood so close that she could feel the power and bad humor radiating from him.

Of course he didn’t move, as that would have been the polite, civilized thing to do. He kept his gaze locked on hers as he returned the rock to its place, and he looked entirely suspicious of her. What did he think, she had come here for nefarious reasons? The idea almost made her laugh.

“If you donna stand apart from fear, then given our previous conversation, I might only surmise you believe yourself superior to a few Scots.” He waited for her to deny it.

Bernadette smiled slowly. “The only Scot I believe myself superior to is you, Mr. Mackenzie.”

One corner of his mouth turned up. “I would expect no different of the Sassenach.”

“Of what?”

The dark smile spread across his lips. “English,” he said.

“If being English means that I believe in civility and manners, then yes, I suppose you should expect it of me.”

His smirk deepened. “I advised you no’ to attempt to shame me, Miss Holly.”

“And I advised you not to try to intimidate me.”

“You advised me no’ to threaten you, lass.”

He would quibble with her now? He could quibble with Avaline all that he liked, but not with her. There was a limit to what Bernadette would do to help this marital union, and speaking to him beyond what was absolutely necessary exceeded that limit. She thought about advising him of that, but decided that she would do best to keep her mouth shut and remove herself before she said something untoward. “Please excuse me.” She stepped around him and walked into the center of the room.

“Miss Holly, will you join us for wine?” Lady Mackenzie asked, spotting her.

“No, thank you,” Bernadette said politely.

“Rabbie, darling, will you?”

Rabbie. That was the first that Bernadette had heard his given name said out loud. Funny, but he didn’t seem like a Rabbie to her. That name belonged to someone congenial and hospitable. He was more like a Hades. Yes, that suited him. Hades Mackenzie, the rudest man in the Scottish Highlands.

“Aye,” he responded to his mother, and accepted the glass of wine Frang held out to him. Bernadette nudged Avaline and whispered she should speak to her fiancé. Whether Avaline took her advice, Bernadette didn’t know, because she walked away, putting as many people and as much space between her and that ogre as she could.

In doing so, she quite literally bumped into Captain Mackenzie.

“I beg your pardon, Captain!” she said, alarmed that she had inadvertently stepped on the man’s foot as she’d glanced over her shoulder to see where the ogre was now.

He caught her elbow and steadied her. “Good evening, Miss Holly,” he said pleasantly.

“I’m rather surprised to see you here tonight. I thought you’d be at sea by now.”

“Aye, as did I. Alas, our ship needs a wee bit of repair. I’ll be a landlubber for a time.” His eyes twinkled with his smile.

Bernadette was again struck by how different these brothers were in mien.

“You’ve met my sisters, have you no’?” he asked.

“I have, indeed.”

“You are acquainted with every Mackenzie of Balhaire, then,” he said with a chuckle.

Unfortunately.

He suddenly leaned forward and whispered, “Have you a verdict on Miss Kent’s fiancé? Does he suit her, then?”

Bernadette could feel herself coloring. What was she supposed to say to that? “Ah...well,” she said, and paused to clear her throat. “It’s all so very new, isn’t it? I suspect they will take some time learning about each other.”

Captain Mackenzie blinked. He slowly cocked his head to one side, his gaze shrewd, and smiled very slowly. “Aye, then, you donna esteem him.” Bernadette opened her mouth to deny it, but he waved his hand. “Donna deny it, lass—it’s plain.”

“I scarcely know him. I’ve not made any judgment.”

He chuckled at that bold lie, sipped his wine, then put the glass aside. “Donna believe everything you see, Miss Holly. My brother is a wee bit hardened, that he is. But he’s suffered a great loss and has no’ come easily back to the living. On my word, the lad is a good man beneath the hurt.”

A loss? Hurt? She tried to imagine what sort of loss might make a man so unregenerate, but couldn’t think of a single thing. She’d lost her husband and her baby, and she wasn’t so hardened. What possibly could have happened to him?

“Ah, there is Frang,” Captain Mackenzie said. “We’ll dine, now, aye?” He stepped away.

Bernadette was still trying to make sense of what the captain had said when Lady Mackenzie arranged them all for the promenade into the dining room. Naturally, Bernadette brought up the rear. She was seated next to Mrs. Vivienne Mackenzie with Avaline across from her. Next to Avaline sat the man who had suffered such an incomprehensible loss, apparently, as to have made him entirely contemptible.

As the meal was served, everyone was laughing and talking at once. Bernadette was especially enjoying the meal—it was the first decent thing she’d had to eat since arriving in Scotland, and it was delicious. A soup thick with chunks of fish, a pie bursting with savory meat and potatoes. The cook Mr. MacDonald had found for Killeaven didn’t know how to prepare food like this, apparently, for everything she’d made thus far had tasted bland and, at times, even bitter.

Bernadette made small talk with Mrs. Vivienne Mackenzie, who told her about her children, including their names, and their traits. Bernadette politely answered the questions Mrs. Mackenzie put to her. How long had she been in the Kent employ? Nearly seven years. How did she find Scotland? Quite beautiful.

Lady Mackenzie and Lady Kent were engaged in a discussion of the wedding ceremony and the celebrations around it. Lady Mackenzie was quite animated in her descriptions of Scottish wedding customs. “No, you actually jump over the broom” Bernadette overheard her say to Lady Kent.

There was a lull in the chatter between Bernadette and Mrs. Mackenzie when the latter’s husband caught her attention and she turned away.

Bernadette glanced across the table at Avaline. She looked unhappy. Bernadette very surreptitiously nodded in the direction of her fiancé. Avaline glanced at the man, then haltingly inquired if Mackenzie had received his education at a university.

“Aye,” he said.

That was all he said—nothing more, no explanation of when or where or anything else to put Avaline at ease, the lout.

Avaline pushed a bit food around her plate, then said suddenly, “Which university?”

He paused in his eating. “Does it matter to you, then?”

He asked it in a way that sounded as if he was somehow offended, and Avaline’s eyes widened. “No! No, of course not.”

“Of course it does,” his mother said kindly to Avaline, having caught that part of the conversation as well. “Rabbie attended St. Andrews, just as his brothers did before him.”

Avaline nodded and gave Lady Mackenzie a faint smile of gratitude. She picked up her fork, took a small bite of food, then put down the fork. “Did you have a favorite governess?”

For heaven’s sake. Bernadette hadn’t meant Avaline to ask that question, but had used it merely as an example to spur Avaline’s own thinking of how she might engage this man.

Her fiancé put down his fork, too, and turned his head to her, so that he might pierce her better with his cold glare. “We didna have a governess,” he said, his gaze straying to Bernadette. “It is no’ the way of the Highlands.”

Avaline dropped her gaze to her plate.

The beast glanced across the table to Bernadette, as if he knew she was the one to have put the thought in Avaline’s head. Well she hadn’t meant for Avaline to take her so literally. “Then what is the way of the Highlands?” Bernadette asked pertly.

“Pardon?” he asked, clearly not anticipating a response from her.

“If you were not minded by a governess, then how were you raised? What is the way of the Highlands? A nursemaid? I had a nursemaid until I was eight years old.”

“We were raised by wolves,” he said. “Is that no’ what is said of Highlanders in England?”

The conversation at the table slowly died away, and now everyone was listening. Bernadette smiled sweetly. “I wouldn’t know what is said of Highlanders in England, sir. We rarely speak of them.”

Captain Mackenzie laughed.

Bernadette glanced at Avaline, silently willing the girl not to shake with uneasiness sitting next to him.

Down the table, Lord Kent’s voice rose with the unmistakable hoarseness of too much drink. “Enough of nursemaids and Highlanders and whatnot. Tell me now, laird, how does your trade fare? I might as well inquire, as it will all be in the family soon enough.” He laughed.

Miss Catriona Mackenzie, seated next to her father and across from Lord Kent, choked on a sip of wine, coughing uncontrollably for a moment.

“Well enough,” the laird said quietly, and leaned to one side to rub his daughter’s back.

“Aye, well enough when we avoid the excise men,” Rabbie Mackenzie said, and chuckled darkly.

That remark was met with stunned silence by them all. Bernadette didn’t know what he meant, really, but his family seemed mortified.

Lord Kent seemed intrigued.

Suddenly, Captain Mackenzie laughed, and loudly, too. “My brother means to divert us,” he said jovially. “He is master at it, so much so that we donna know when he teases us.”

Bernadette did not miss the look that flowed between brothers, but Captain Mackenzie continued on. “I am reminded of an occasion we sailed to Norway, Rabbie. You recall it, aye?”

“I’ll no’ forget it,” his brother said.

The captain said, “We sailed into a squall, we did, the seas so high we were pitched about like a bairn’s toy. A few barrels of ale became unlashed and washed over the side with a toss of a mighty wave.”

Bernadette’s stomach lurched a tiny bit, the memory still fresh in her legs and chest of roiling seas.

“What a tragedy for you all to lose your ale,” Lord Kent scoffed.

“Aye, but it was,” the captain agreed with much congeniality, politely ignoring his lordship’s tone. “Rabbie and I didna have the heart to tell our crew of the loss, no’ with two days at sea ahead of us, aye? When the seas calmed, and the men looked about for their drink, I said to Rabbie, ‘We’ll be mutinied, mark me.’”

Lord Mackenzie smiled, amused by that.

“Rabbie said, ‘No’ on my watch, braither.’ When I asked what he meant to do, then, he said he didna know, aye? But he’d think of something.”

“Oh, aye, he’d think of something, would he?” Catriona said laughingly.

“What happened?” Avaline asked eagerly, held rapt by the captain’s tale.

“He gathered the lads round, and told them a fantastic yarn of the sea serpent who stole their ale.” Captain Mackenzie leaned forward and said in a low voice, “Now the lads, they’ve been a sea for a long time, they have, and they donna believe in sea monsters. But Rabbie was so convincing in his telling of it that more than one began to crowd to the middle of the main deck, fearing one of the serpent’s arms would appear to pull them into the sea along with their drink.” He laughed and settled back in his chair. “They didna fret about their ale, no’ after that tale. My brother spoke with such confidence they couldna help but believe him.”

Bernadette wondered after an entire ship of men who would fall prey to such a ridiculous tale. And yet, across from her sat a pretty, cake-headed girl, eyes wide with delight as she listened to Captain Mackenzie. Fortunately, Avaline seemed to have forgotten all about the ogre sitting next to her.

And yet it hardly mattered that Avaline’s attention had been diverted, for the ogre appeared quite content to be forgotten. He sat back in his seat, his expression unreadable as everyone around him laughed at that ridiculous story. But his hand was curled into a tight fist against the table, and Bernadette had the distinct impression he was holding himself in check. From what? Was he angry? Did he dislike his brother’s amusing tale?

“Shall we retire to the sitting room?” Lady Mackenzie asked, and stood.

The ogre stood, and, rather miraculously, he held Avaline’s chair out so that she might rise. Avaline didn’t seem to notice the polite gesture at all—her gaze was on Captain Mackenzie and she hurried to his side to ask him something about the story he’d just told as they began to make their way out of the small dining room.

Once again, Bernadette followed behind the rest of them, only this time, she had company. Rabbie Mackenzie fell in beside her, his hands clasped at his back. He said nothing, and certainly neither did Bernadette. She was aware of how much his body dwarfed hers. She felt unusually small next to him, and imagined how helpless Avaline would feel beside him. She tried not to picture their wedding night, but it was impossible once the thought had crowded into her head—Bernadette could see him, tall and broad and erect...

Goodness, but she imagined that in very vivid detail, and carefully rubbed her neck, trying to erase the heat that suddenly crawled into her skin.

The room in which they’d gathered was another sitting room, with two settees and a few armchairs, and a few spare dogs eager to greet everyone who entered the room.

At the far end of the room was a harpsichord. Bernadette sighed softly to herself. She knew where this was headed. They would have the obligatory demonstration of Avaline’s “abilities.” Avaline was terrified of performing before others, and frankly, Bernadette was terrified for her. She had little real talent for it, and the harder she tried, the worse she sang. It was a cruel fact that women of Avaline’s birthright were expected to excel in all things domestic—in managing their household, in needlework, in art and song. She was also expected to demonstrate how pleasingly accommodating she was by showing an eagerness to perform at the mere invitation. And woe to the woman who did not excel at singing, for she couldn’t escape her duty to display her so-called wares.

Bernadette’s talent was in playing the harpsichord. She, too, had been born to this perch in life...but she’d fallen from it.

“Here then, allow my daughter to regale us with a song,” Lord Kent said almost instantly, without any regard for his daughter’s feelings on the matter, or her lack of talent. He was well aware how it frightened Avaline to stand before anyone and sing—the good Lord knew it had been a source of contention between them many times before this particular evening.

“Miss Holly, you will accompany her,” his lordship decreed.

All heads swiveled about to where Bernadette stood just inside the door, the ogre at her side. She bristled at the command, could feel the heat of shame flood her cheeks. As if she were a trained monkey like the one she’d once seen in a London market.

“Go on, then,” Mr. Mackenzie said. “Donna draw this out any more than is necessary.”

“You have nothing to fear in that regard,” she muttered, and walked to the front of the room—for Avaline’s sake, always for Avaline’s sake—wiping her palms on the sides of her gown as she went. She sat on the bench before the harpsichord, glanced up at an ashen Avaline and whispered, “Look above their heads, not at them. Pretend no one is here, pretend it is a music lesson.”

Avaline nodded stiffly.

Bernadette began to play. Avaline began to warble. She held her hands clasped tightly at her waist, her nerves making her sing sharp to the music. At last, the poor girl finished the song to tepid applause. The ladies, Bernadette noticed, were shifting restlessly in their seats. And in the back of the room, standing exactly where she’d left him, stood Rabbie Mackenzie. His head was down, his arms folded, his expression one of pure tedium.

But the song was done, and Avaline moved immediately to sit, as did Bernadette, but Lord Kent, slouching in his chair, his eyes half-open after the amount he’d drunk, waved her back. “Again, Avaline. Perhaps something a bit livelier that won’t put us all asleep.”

Avaline’s shoulders tensed. She turned to Bernadette, her eyes blank now, her soul having retreated to that place of hiding. Bernadette managed a smile for the poor girl. “The song of summer,” she said softly. “The one you like.”

Avaline nodded. As she moved to take her place next to the pianoforte, and Bernadette played the first few chords, she looked up to see if Avaline was ready, and noticed, from the corner of her eye, that Avaline’s fiancé had exited the room. How impossibly rude he was! It made her so angry that she hit a wrong chord, startling Avaline. “I beg your pardon,” Bernadette said, and began again.

This time, when the song mercifully ended, it was Captain Mackenzie who rose to see Avaline to a seat, complimenting her on her singing as he did.

The evening dragged on from there. Bernadette stood near a bookcase, pretending to examine the few titles they had there, impatient for the evening to come to an end. She was trying desperately not to listen to Lady Kent and Avaline attempt to converse with the Mackenzie women about the blasted wedding.

At long last, his lordship rose, signaling to his party. They could at last quit this horrible place and return to Killeaven.

None of the Mackenzies entreated them to stay, but eagerly followed them out like so many puppies—with the notable exception of Avaline’s fiancé, of course—and called good-night as they climbed into the coach. Even his lordship took a seat inside the coach, having instructed a man to tether his horse to the back of it. As soon as they rolled out of the bailey, he turned a furious glare to Avaline. “You are a stupid, vapid girl!” he said heatedly. “You have no knowledge of how to woo a man! What am I to do if he cries off? What will I do with you then?”

“I beg your pardon, Father, but I tried—”

“You asked after his favorite governess!” her father shouted at her, spittle coming out of his mouth with the force of his voice. “Haven’t you the slightest notion how to bat your eyes? And you,” he said, swinging his gaze around to Bernadette.

“Me?”

“Yes, you! You’re a wily woman, Bernadette. Can you not teach her to be less...vapid?” he exclaimed, flicking his wrist in the direction of his daughter. “Can you not teach her how to lure a man to her instead of cleaving the line and letting him sink away?”

“The man is entirely disagreeable—”

His lordship surged forward with such ferocity that his wig was very nearly left behind. “I don’t care if he is Satan himself. The marriage has been agreed to and by God, if he cries off because of her,” he said, jabbing his finger in the direction of Avaline, “I will take it out of her hide.”

Avaline began to cry.

Her father fell back against the squabs and sighed heavily, as if he bore the weight of the world on his shoulders. “What have I done to deserve this?” he said to the ceiling. “What sin have I committed that you give me a miserable wife without the ability to give me a son, and a stupid twit for a daughter?”

Needless to say, by the time the old coach had bounced and plodded and bumbled along to Killeaven, the entire Kent family was in tears.

If Bernadette had been presented with a knife during that drive, she would have gladly plunged it into her own neck, just to escape them all.

CHAPTER SIX

AVALINE WAS FINALLY ALONE. She was never alone; there was always someone about to tell her what to do, what to say, how to behave.

It had been a very long day and a draining evening at Balhaire. Her eyes and her face were swollen from sobbing, and her mother’s attempt at making a compress had only angered her. She’d sent her mother from the room, had locked the door behind her.

Now, Avaline had no tears left in her. What she had was a hatred of her father that burned so intently she felt ashamed and concerned God would strike her dead for it. She hated how her father treated her, but she hated worse how she sobbed when he said such awful things to her. She was quite determined not to, but she could never seem to help herself.

What she told him was true—she had done her best this evening. She had tried to engage that awful man as Bernadette said, had tried to be pleasant and pretty and quiet. Nothing worked. What was she to do? He stared at her with those dark, cold eyes. His jaw seemed perpetually clinched. He rarely spoke to her at all, and when he did, every word was biting. He hated her. Which was perfectly all right as far as Avaline was concerned, because she hated him, too, hated the very sight of him.

And the singing! Avaline groaned at the humiliation she had suffered. Couldn’t her father hear with his own ears that she wasn’t good enough to hold entire salons captive? He blamed her for her lack of talent and had once accused her of intentionally singing poorly only to vex him. What on earth would possess her to humiliate herself before others merely to annoy her father?

Avaline rolled onto her side and stared at the window, left open to admit a cool breeze. She couldn’t see beyond it, but she imagined she could hear the sea from here. It was probably only a night breeze rustling the treetops, but she wanted to imagine the sea.