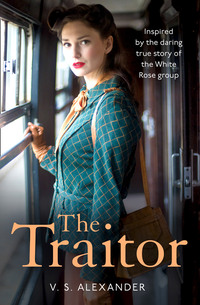

The Traitor

THE TRAITOR

V. S. Alexander

Copyright

One More Chapter

a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © V. S. Alexander 2020

Cover design by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2020

Cover images © Shutterstock.com

V. S. Alexander asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008402372

Ebook Edition © 2020 ISBN: 9780008402365

Version: 2020-02-25

Outstanding praise for the novels of V. S. Alexander

The Irishman’s Daughter

“Skillfully blends family ties with the horrors of a starving country and the hopefulness of young love.”

—Booklist

“Written with hope for a better tomorrow, V. S. Alexander gives readers an intimate heart-wrenching account of the unimaginable suffering of those who clawed their way through Ireland’s darkest years.”

—BookTrib

The Taster

“Alexander’s intimate writing style gives readers openings to wonder about what tough decisions they would have body of nuanced World War II fiction such as Elizabeth Wein’s Code Name Verity, Anthony Doerr’s All the Light We Cannot See, and Tatiana de Rosnay’s Sarah’s Key. Book clubs and historical fiction fans will love discussing

—Library Journal

The Magdalen Girls

“A haunting novel that takes the reader into the cruel world of Ireland’s Magdalene laundries, The Magdalen Girls shines a light on yet another notorious institution that somehow survived into the late twentieth century. A real page-turner!”

—Ellen Marie Wiseman, author of The Life She Was Given

“Alexander has clearly done his homework. Chilling in its realism, his work depicts the improprieties long condoned by the Catholic Church and only recently acknowledged. Fans of the book and film Philomena will want to read this.”

—Library Journal

Dedication

To those who fought and died for freedom

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Outstanding praise for the novels of V. S. Alexander

Dedication

Prologue

Part 1: The White Rose

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Part 2: Traitors

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Footnote

A Reading Group Guide

About the Author

About the Publisher

PROLOGUE

Kristallnacht, November 9, 1938

The Night of Broken Glass

I n the dark, the mind can play tricks.

That’s what I thought when the sounds entered my ears, faint at first, like the play of droplets in a fountain, followed by distant crashes that cracked and splintered the air. I wiped the sleep from my eyes, reached for my glasses, and peered out the window above my desk. The silver clock on my desk read past one in the morning. It was November ninth, the fifteenth anniversary of the failed Beer Hall Putsch, a time of National Socialist memorials and celebrations across Germany for the martyred Nazis. Everyone should have been asleep, but other equally ominous noises filled the air as well.

Muffled laughs and jeers filtered through my window. I opened the latch, hearing the voices spreading across Munich, which seemed to come from every corner of the city, from the very earth itself. Indistinct voices, broken in the air, chanting, “Juden, Juden, Juden,” fell upon my ears. I shivered against the shouted barrage of anger and hate.

I switched on my desk lamp and a sickly yellow glow washed over the papers that lay upon my blotter—I’d spent long hours studying before bed. I rubbed my tired eyes, put on my glasses, cupped my hands around my face, and peered through the soot-smudged window of my fourth-story bedroom on Rumfordstrasse.

I looked beyond the needlelike spire of the Church of St. Peter, “Old Peter” as my mother and father called it, and past the stone buildings that lined the streets, smoke spiraling up in a corkscrew, pummeling the clouds that concealed the full moon. Flames flickered on the horizon as the dark smoke spread across the sky like ink dropped in a bucket of water.

Munich was constructed of stone and wood, and the fire brigade would be there soon enough to extinguish the blaze. A feeling I had known few times before settled in my stomach. The sensation reminded me of the time, as a child of seven, I had wandered away from my mother in a department store when we first came to Munich. A peculiar fear filled me. A kind old man dressed in a blue suit that smelled of tobacco and spicy cologne helped me find my mother. The man spoke German with a heavy accent and wore a round cap on his gray head. My mother swept me into her arms and forgot about her anger with me for wandering off. She told me later that if it hadn’t been for the Jewish man, someone might have snatched me away. Her voice was flat and calm, nothing like the voices outside my window.

This November evening brought that earlier dread back to me, a crushing culmination, like brick piled upon brick, of the changes that had swept across the city as National Socialism spread at first in small steps then in insidious leaps and bounds. My Jewish friends, who had once been numerous since the time the old gentleman had been my deliverer years earlier, were now distant, many telling me that I was better off without them. Their words saddened me as they drifted away. I wanted to keep them as friends even as they preferred not to be seen or heard, sheltering in their homes like secretive, silent mice.

In 1938, the Reich pressed its incrimination and repression not only upon my family but upon every citizen who wasn’t a fervent Nazi. Sometimes the tension that vibrated through Munich bordered on paranoia, with a terrible, blood-churning excitement that came with a terrible cost—one never knew when the Gestapo might come for your neighbor or you.

As these thoughts raced through my mind, the fire grew larger, the overcast reflecting a hellish mixture of blazing yellow and orange, streaked by flowering blooms of black. Then, there were more crashes, the sounds of ripping metal and breaking glass, but no alarms sounded.

At sixteen, I was too young to leave my parents’ house without permission, but old enough to be curious—and frightened—by what I saw and heard. I tiptoed down the hall and peered into my parents’ bedroom. They slept undisturbed under their blankets, their sleepy breaths rising and falling in rhythm.

I crept back to my room, turned off my lamp, and tried to fall asleep while fearing for the city I called home.

“Talya,” my mother shouted the next morning at my door.

I shot up in bed. “Yes?”

Mary, my mother, tapped her foot as she always did when I had overslept.

“You’ll be late for school.” She turned in the hall toward the kitchen, her black dress ruffling around her body, her shoes clicking on the wooden floor. My mother always kept her bourgeois attitude, despite the fact that living in Germany was harder than both my parents had anticipated after leaving our Russian home behind. She always looked, no matter the time of day, as if she was going shopping. Another habit that she refused to give up was calling me by the diminutive form of my name. That mannerism irritated me because I was no longer a child—I had turned sixteen on the sixteenth of May. All of my girlfriends, and certainly the boys I knew and liked at school, called me by my full name—Natalya.

“There’s no school today—it’s a national holiday.” I yawned and stretched toward the window to see if the fire was still burning.

She returned, her eyes flashing in irritation at my sleepy attitude. “Herr Hitler has canceled the holiday. Herr Hess is speaking tonight. No matter if there’s school. If not, you can find yarn for me so I can mend your father’s socks.”

I was at a loss. If the holiday was canceled, would stores be open or closed? And the task of finding dry goods was becoming almost impossible as the availability of fabrics dried up to support the needs of the expanding Wehrmacht. I washed, dressed, and joined my parents at the breakfast table.

“Did you see the fire?” I asked my mother after I sat down.

My mother busied herself with the pots on the stove and didn’t answer. My father, Peter, lifted a spoonful of porridge to his mouth and gave me a stern look. His eyes narrowed and he said, “Hooligans. Such nonsense.” He took a bite and pointed the spoon at me. “Stay away from them.”

“How do you know they were hooligans?” I asked.

My father’s black brows bunched over the bridge of his nose. “Many people are reluctant to talk these days, but some do, even early in the morning, when neighbors gather in the hall.”

“I don’t associate with troublemakers,” I assured him as I dug into my oatmeal. My father’s approach to life, unlike my mother’s breezier style, was all business, suitable for a strict disciplinarian. As I grew into my teenage years, I resented the absolute commands that he spewed toward me like platitudes. “No” and “don’t” were principle words in his vocabulary.

After eating, I returned to my room and studied the algebra problem I’d been working on the previous evening. Frustrated by my inability to solve it, I tossed the troublesome paper and pen next to my biology text. The book lay open to its title page with the spread-winged eagle perched on the encircled swastika; it gleamed up at me as if its black ink had been printed yesterday. We lived with those symbols every day—we had no choice.

I cleaned my glasses and wondered if I could sneak out with my friend Lisa Kolbe. She was more knowledgeable about life and worldly interests than I was. I believed she was prettier, more outgoing, with a less melancholy outlook than mine—inherited from her German parents—far different from living in my Russian father’s household. Lisa had a way of making friends that I also admired. We’d known each other for years because we were only a few months apart in age and lived in the same building.

Two taps sounded on the floor from the ceiling below. They were soft, but I felt their vibrations through my shoes. Lisa was sending me our long-held signal to meet. I put on my coat and walked to the sitting room.

My father was finishing his tea and reading an illegal book—a German translation of the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas. He kept it, and a few other illegals concealed behind the bookcase, as if their makeshift hiding place would never be discovered. My father would have refrained from reading a banned book in public, and because our family kept to ourselves, there was little likelihood his cache would be found.

I watched him for a moment as his eyes drank in the words. Soon he would put down his reading and go to the apothecary shop where he worked as an assistant to the pharmacist—a job similar to the one he held in Russia before we moved to Munich.

My mother gave me Reichsmark for black yarn if I should happen to find a store open. This came after a stern admonition from my father, “Make sure you stick to your business.” I kissed my parents good-bye and stepped into the dusty hall, being careful to tread lightly down the steps. Lisa stood in the half-dark corridor, attired in her tights and jacket, her face partially lit by the single bulb at the top of the stairs. Her blonde hair, verging on silver, was cut in a stylish sweep around her face and ears. The upturned mouth I knew so well offered the usual appearance of a pert smile.

“So where are we headed?” she asked.

“Out for yarn.”

“Exciting,” she replied and feigned a yawn.

“I know.”

“My parents have left for work.” Her smile shifted to a mischievous grin. “We must see what happened last night!”

I was as excited as she was about discovering what had gone on, and more than willing to stretch the limits of my father’s orders. We sprinted down the remaining steps and out the door. A listless breeze carried the lingering odor of burned wood.

“Did you see the fire?” I asked as we walked through the narrow streets of the city center. To the west, the twin towers of the Frauenkirche loomed near the central square of the Marienplatz.

“Only the red in the sky.”

We were engrossed by the strange timbre of the day. The streets were quiet, but here and there people strode past, eyes cast downward, barely giving us a glance. Sometimes they disappeared up alleyways like phantoms in the shadows.

Several young men sat on benches smoking cigarettes, or leaned against buildings, looking as if they were fighting off the effects of a long, drunken night. They were members of the SA, “brownshirts,” as we called them. One particularly surly fellow with a thick jaw and full head of sandy-colored hair ordered us to stop. “Juden?” he asked. We shook our heads and said “Nein,” and after we presented our school papers, which we always carried with us, he let us go.

“Can’t they tell we’re not Jews?” Lisa asked, but I knew she was trying to make a joke. Her words dripped with sarcasm. One of our dear friends, a Jewish girl whom we hadn’t seen in several months, was as blonde and blue-eyed as any Aryan could be. Yet, she was subject to the laws oppressing the Jews. Nothing about these restrictions was fair.

Soon we came upon the building that had burned—a synagogue. I had passed by it many times. It was a solid stone building with a large circular window encased in what appeared to be a turret, but the flames had charred everything, leaving the window a round, empty hole like the removed eye of a Cyclops. Most of the roof had collapsed upon itself. The stone masonry stood blackened, but some parts had been turned the color of ash by the intense flames. The structure with its burned-out arched windows and doors was as ugly now as the naked trees that stood apart from it.

We dared not move too close because members of the SA guarded the building, keeping those away who might want to loot it or perhaps save an artifact. Two women stood behind us, tears streaming down their cheeks as they dabbed their eyes with handkerchiefs. From their muffled sobs, I could tell they didn’t want to call attention to themselves.

They shuffled away and a nicely dressed young man strode to my side and took off his hat. He was tall with hair a mixture of blond and brown, parted on the left and swept back to the right in the style most men wore. His wide-set eyes were framed by an attractive face, and even with a glance I surmised that he was intelligent and a bit on the cunning side. From his rigid stance to the set jaw, he exuded those qualities.

“The SA set it on fire with gasoline, and then tried to throw the Rabbi in the flames,” he said in a low voice while staring at the synagogue. “He wanted to save the Torah scrolls.”

Lisa and I looked at each other, not sure what to say.

“They’re dogs, all of them,” he continued. “They had the Rabbi arrested. He’ll end up in Dachau for sure. Pigs.” He turned our way. “Who are you?”

I started to answer, but Lisa stepped in front of me and said, “It’s none of your business. Who are you to ask?”

Being the introvert, I fell silent, feeling somewhat sorry for the man who had expressed his sympathy for the Rabbi and the tragic arson. Out of kindness, I smiled at him and his eyes locked upon mine. A jolt of attraction sparked between us for a second, and the hair on my arms prickled with gooseflesh.

“I’m sorry to bother you, but I won’t forget you,” the man said and tipped his hat. After giving me a look, he disappeared around a street corner behind us.

“That was strange,” I told my friend, while absentmindedly positioning my glasses on my nose. The electric thrill still lingered on my body. Lisa stood composed, sassy, and stylish a few steps away. I’d never considered myself to be pretty, always judging myself: tall and gangly with perhaps too much black hair. My glasses didn’t help my confidence with boys either.

“Let’s leave before we become more conspicuous,” Lisa said, implying that by merely observing the synagogue we had already done so.

She was right. One always had to toe the line—to be the good German and not make waves or create a fuss, because any action outside the law could lead to misfortune.

As we left, I asked Lisa, “What has become of our Jewish friends? I fear for them now more than ever.” And behind that question was a broader indisputable fact: Lisa and I didn’t agree with the Reich’s laws and doctrines. There was no exact day we formed that viewpoint, but the propaganda from the state-run newspapers and radio, the men who marched off to war and never came back, the rationing, the building tension in the air allowed us to reach that conclusion. We silently understood what the consequences were for such thinking. But what could we do about the Nazis?

As we walked about Munich, we saw the destruction that was perpetrated for the “protection” of Jewish property—the looting of goods by the SA and others. Many people emerged to look at the damage, walking like the dead as they passed broken windows, burned storefronts, and looted showrooms. Lisa and I knew that the world was changing for the worse.

At the Schwarz Restaurant windows were broken out; Adolf Salberg Fineries on Neuhauserstrasse had been firebombed—the large Salberg sign was a twisted mass of metal; Heinrich Rothschild’s hat and finery store had been vandalized and words against Jews whitewashed on the windows; the Sigmund Koch music store looted; display windows smashed at Bernheimer home furnishings and art store; and perhaps most shocking of all, the large, popular department store, Uhlefelder on Rosental, had been looted and vandalized.

My father worked for one of the few remaining Jewish business owners in Munich. Lisa and I found him standing on the sidewalk in front of the broken windows of the apothecary, shards of glass like fractured diamonds littering the street.

“What are you doing here?” my father asked sternly when we approached. His broad jaw, so typical of the men in his Russian family, was clenched. “Your mother sent you out for yarn, not to roam the streets.” He picked up a broom propped against the side of the shop and pointed the handle at us. “Go home! Now! You’ve seen enough.”

Mr. Bronstein, my father’s boss, poked his head out of the shattered window. His pinched face, red eyes, and trembling hands showed the pain incurred by the destruction at his shop. Two brownshirts strolled down the street. My father threw the broom down, grabbed Lisa and I by the shoulders, and whispered to us to stand still.

“Are you a Jew?” one of the men shouted from down the street.

My father shook his head but stared defiantly at them.

“Go on, then,” the man ordered, strolling toward us and placing his hand over his holstered pistol. “Where is Bronstein?”

The owner, small and thin, appeared in the doorway. The man rushed at Mr. Bronstein, shoved him inside the store, and shouted, “Clean up your mess, dirty Jew. Is this how you run a business? Well, you won’t for long. You have to pay for this damage.” A slap and a cry echoed from the shop.

My father swiveled us on the sidewalk toward our home, his arms trembling as he guided us. We walked home in silence. As we neared our door, I realized that overnight Germany had embraced death over life.

The yarn was forgotten.

CHAPTER 1

July 1942

If I had believed the world was flat, the steppes would have provided the proof as the earth spread in an unbroken line to a distant horizon. The vast land stretched before me, a patchwork of green grasses that undulated in wind-whipped waves along with the brown stubs of harvested winter wheat, other fields dissected only by the gray bark of infrequent trees or the cubed wooden frames of farmhouses not destroyed in the Wehrmacht’s advance.

I was on a cramped train, separated from the army men, heading to the Russian Front as a volunteer nurse for the German Red Cross.

Some of the fields had been burned and only the blackened earth remained, but as surely as the sun rose, the ground had to be tilled and tended by the solitary figures of peasant farmers, who stood with pitchforks in hand or sat upon a horse-drawn wagon—if the poor people could force another crop from the ground.

Somehow a lucky few had survived. Perhaps the Wehrmacht needed the workers, toiling under slave labor to transport grain back to Germany, or perhaps they had been spared from death by a “beneficent” Nazi officer.

It was the first time I had been in Russia since our family had fled from Leningrad during the first phase of the Five-Year Plan in 1929. I was seven years old then. My father had seen firsthand the disappearance of those who didn’t meet the work quotas set up by Joseph Stalin—they vanished in the night never to be seen again, usually sent to their deaths in labor camps. My father had scraped enough money together for us to move to Germany, where he hoped we would have a better life. Because my mothers’ parents were German, we were granted citizenship before the full rise of National Socialism.

But the war was in full bloom after the September 1, 1939, invasion of Poland and depending on the train’s location, we looked out upon a land that retained its raw beauty or rolled past a landscape blasted by conflict. In Warsaw, I witnessed the desperation of Polish nationals, who had surrendered everything to the Nazis except their humanity, as I slipped a piece of candied sugar to a little girl who offered me a flower, while gazing upon the brick ghetto walls that confined so many Jews. Soldiers herded emaciated people in and out of the gates, marching them in lines toward some unknown destination. I had become numb to the horrors, learning over the years that I could do little to fight against the Reich.