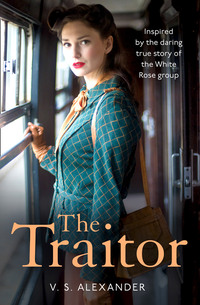

The Traitor

“Do you have a husband?” I asked, wanting to steer the subject away from killing.

“Oh, yes, a strong, handsome man whom the Nazis would shoot on sight if they could get their hands on him.” She lifted her hands from the bed and fluttered her arms like wings. “But he’s free as a bird now. I see him when he can sneak away, deep in the night, in the dark, when we both can take refuge from our troubles.”

“He’s a partisan,” Alex said, turning his head toward me from his seat on the rug. “A man of conviction and principles fighting against …”

He stopped, but I suspected the next word to come from his mouth might have been “evil.”

Alex reached for a book on the table and lifted it in front of him. “Crime and Punishment—one of my favorites. We can read from it if you’d like.”

Sina’s right hand inched toward the pillows until her fingers rested underneath one of the slipcases. I considered her movement a bit strange, but had no idea what she was doing until she withdrew a black pistol from its hiding place.

I gasped and felt the blood drain from my head.

Alex thumbed through the book, apparently unaware of Sina’s action. “Dostoyevsky,” he said, without looking up, “is the most Christian of all the Russian writers, in my opinion.” He lifted his gaze from the pages for a moment and glanced at our host.

The black barrel was pointed directly at us. I was behind Alex and, from above, a rich thatch of brownish hair swirled around the part in back. I couldn’t see his face, but I wondered if the color had drained from his as it had from mine.

Without raising his voice, he said, “Sina, please put that away—you might accidentally shoot one of us.”

“It wouldn’t be an accident,” she replied. Her children sat calmly by her side looking intently at both of us—me in the chair and Alex sitting on the rug in front of me.

“We’re supposed to kill all Germans,” she said and paused. “But you aren’t like all Germans. In fact, you’ll never be rid of the Slav in your soul.”

The trigger clicked and the hammer popped into its resting place. I yelped, but there was no explosion, no bullet smashing into my skin.

“See, you’ve done nothing but frighten Natalya,” Alex calmly shook a finger at her. “Shame on you.”

I clutched the side of the chair to keep from shaking out of the seat. “You scared me to death, Sina. That was a dirty trick.”

“An old trick,” Alex said. “I lived through it the first night we met, and I should have warned you, but I didn’t know she repeated it for all the Germans she meets.” He turned his head and gave me a wink.

“I’m not stupid enough to keep a loaded pistol around my children.” Sina smiled, returned the weapon to its place under the pillow, and swept up Dimitri and Anna in a bear hug. “Soon they will be old enough to handle the pistol themselves. I look forward to seeing them kill their first enemy fighter.”

The thought of Russian children taking shots at German soldiers appalled me. Dimitri and Anna would be slaughtered like pigs. “May I have another drink?” I asked, lifting my cup.

“Please, help yourself,” Sina said.

I poured another vodka. The liquor took over and my shock faded to a shaky tension; we sang and laughed for several hours until Sina played a melancholy folk song on the balalaika. The melody seemed somewhat familiar from long ago in my childhood, but was now too distant in my memory for me to join in. Alex knew it by heart and sang with Sina while I did a slow clap in time with the beat. The children danced in front of the bed, joining arms and moving their legs in unified step.

The hour grew late and rain pattered against the walls, keeping us there longer than we’d anticipated. The oil lamp flickered, but rather than replacing the fuel, Sina allowed it to sputter out and we talked in the dark as the children settled into bed. We adults looked through the open window as shells exploded in the east, illuminating the starry expanse, now free of clouds, with brilliant bursts of yellow and white.

As the night lingered, Sina, slowed by vodka and perhaps her own sadness, sang a melody that brought tears to my eyes. It started low, never leaving the minor key, and then grew to a high pitch, until I thought the wooden rafters would split from the sound. Finally, the tune dissipated in a soft shift to a major key and died on the breeze that wafted into the hut.

I nudged Alex’s head, which rested against my legs. “It’s time to get back to camp, or we’ll be reported missing.” My words tripped thick and heavy off my tongue.

“Yes,” Alex said, and pushed himself up on all fours before standing on wobbly legs.

We said our farewells, kissed Sina, and promised to visit another night. Alex vowed that on our next trip he would abstain from vodka long enough to have an intelligent discussion about Pushkin and Tolstoy. Sina agreed and, with a final wave of her hand, shut the door.

“She’s delightful,” I said to Alex, and wondered if that was the best way to describe her. Sina was exotic to me, different in a way I had never experienced except in the far reaches of my memory when vague images of Leningrad came to mind. But even those people dredged up from the past were different from her. There was no way to compare the city folk I knew as a child to country folk ravaged by German troops.

We weaved up the road toward camp as I looked into a sky profuse with stars. “I can reach up and touch them,” I said, shifting my glasses and craning my neck toward the heavens.

Unaware of where I was stepping, I missed a large puddle by the width of my foot and decided to take off my shoes to avoid coating them with muddy water. I wrapped my arms around Alex’s waist and savored the still warm feeling of the vodka in my stomach and the cool, damp earth squishing between my toes. In the morning, I would pay dearly for my excess. However, rinsing off the mud would be easier than ridding myself of a hangover.

In spite of the evening’s indulgences, I’d found a true friend in Alex. That alone made the night worthwhile.

The rain began in earnest a few days later and turned the camp into a morass of swampy earth and dripping branches. I imagined what the colder fall and winter weather would bring, when conditions would truly worsen.

Wounded soldiers poured into the camp daily, and the onslaught of injuries, many horrific, made me question my decision to be a nurse. Often I stumbled to bed bone weary and bleary eyed from long hours in the medical tent. One stiff-necked surgeon in particular was a stickler for rules and regulations, including limited rest breaks; no small talk among medics, aides, and nurses; and no smoking in the camp. He made everyone’s life miserable, including my own, performing his surgeries while criticizing my dressing of wounds, my administration of medicines and hypodermics, thus further eroding my confidence. I was thrilled and relieved when he was transferred unexpectedly to a unit farther north.

Alex, Hans, Willi, and another medic, Hubert Furtwängler, often ate lunch together on nice days at a spot near camp, their table dappled in the sunlight coursing through the overhanging limbs of an oak. The men were a snapshot in time, their canteens and tin cups scattered between half-eaten loaves of bread and thick slices of cheese. When the workload was light or they could sneak away for a break, they sat on a fence post near a damaged building and smoked. The thought struck me that they had banded together in a fraternal bond.

The three of them, minus Hubert, often gathered in hushed conversations that ended abruptly when an outsider approached. On the few times I was asked to join them—mostly I passed by with a quick hello—the talk turned to the mundane: the weather, the thrill of duty or its opposite, the drudgery of the medical tent, our longing for home and friends.

I was certain these men, when alone, talked about other things as well—forbidden topics—that only this group dared discuss. I had no proof of this other than the way they interacted with one another: cautious, quiet, hunched, as if secrets were being shared. Any astute Gestapo agent would have questioned them for their actions. One time when they sat smoking, I spotted the remains of a swastika carved into the dirt. Alex had hurriedly tried to blot it out with his boot. The top half of the symbol had been crossed out with a large X.

By September, Willi and Hubert had been deployed to other battalions on the Front and Alex had taken ill. I received this news from Hans.

“Alex has diphtheria.” We stood in a grove of birch trees whose tops had turned to a brilliant burnished gold.

“Diphtheria?” I was shocked because most of us had been immunized against the disease.

“He’s burning up from a high fever, and confined to his bed,” Hans said. “Apparently, he didn’t get the vaccine.” His handsome face looked drawn in the pale light, his cheeks sunken as if the medical corps and its uneven rhythm of work, from boredom to frenzy, and the effects of lackluster army rations had taken their toll. He took off his cap and swatted at a buzzing fly. “I’ll be lucky if I don’t come down with it myself. We’ve given too much blood for the troops, our resistance is low—and there are so many infections in Russia. Well, I don’t need to tell you that …” His lips parted in a half smile, the facial expression I had seen him display most often.

“Please give him my best wishes, if you see him before I do,” I said.

“I will.” Hans placed his cap back on his head. “Walk with me … please.”

I stepped in sync beside him as we headed in the direction of Sina’s home, away from the birch forest and into a clearing where the land stretched to the horizon on all sides and the gray clouds skimmed above us.

Hans took a deep breath, and he seemed to grow lighter from the air. “I’m tired of death … and the war.”

“You need something to take your mind off it,” I said.

“It’s hard being alone now that Alex is sick and Willi and Hubert are gone.” He uttered a faint laugh. “I can never take my mind off it—war will be on my mind as long as we are in it … and probably long after.”

“You’re very serious,” I said.

His gaze narrowed, his brows tightened, as if I had maligned him.

“I didn’t mean that as an insult,” I said quickly. “I meant that you look at things in a different way from other men. The war has touched you.”

We stopped near a rivulet that swirled in a shallow pool on the road and then bubbled into a nearby field. I bent down and stuck a finger in the cool water. I looked back to our camp, which lay hidden by the trees, to the east and west, where the land ended in rolling hills, and then to the south, where the fields spread out to the horizon. Down the road, Sina’s hut stood outlined against the haze.

“I’ve been to Sina’s with Alex,” Hans said. “Did he tell you what we did the other day?”

Not having seen Alex for several days, I shook my head.

“We buried a Russian we found on the plain not far from here.” He squatted near the flowing water and dipped his hand into it. “His head had separated from his rump and his private parts had decayed. Worms crawled out of his half-rotten clothes. We had almost filled the grave with soil when we found another arm. We made a Russian cross, which we put in the earth at the head of the grave.” He paused. “Now his soul can rest in peace.” Hans bowed his head. “Maybe that’s how Alex contracted diphtheria.”

He looked up at me. “I feel such sympathy for the Russian people—knowing what they’ve been through at the hands of our army. I fear that there’s much more going on that we don’t know about as medics and nurses. I think the SS keeps their actions a secret even from the generals. You’re Russian—I’m sure this killing bothers you as well.”

The water reflected the tortured look on his face, but before I had a chance to answer, his mood shifted to one of joy. “Have you heard my choir? I put it together with a few Russian girls and POWs … We do the best we can. I love music and I long to dance. The other night we danced until we collapsed.”

I’d heard the songs, sometimes joyous, sometimes faint, often somber, drift through the medical tent, but work, darkness, and fatigue had kept me from investigating. The voices seemed to come from far away, at odd times of day and night, like the songs of distant angels. “I’d like to hear them. My friend in Munich, Lisa Kolbe, knows more about the arts than I do, and I’ve learned something about music from her.”

“Did you know I have a brother serving here in the same sector?” Hans asked.

“No. Do you see him?”

He stood up from the rushing water and looked to the west. “A few miles from here. His name is Werner. I ride over on horseback when I can.” Hans opened his arms in a grand gesture, which seemed to unleash a sweep of energy into the air. “I’ve developed a passion for riding, and it won’t let go of me,” he said, his voice filling with enthusiasm. “There’s nothing to beat galloping across the plain astride a fast horse, forging your way like an arrow through the head-high steppe grass, and riding back into the forest at sunset, weary to the point of exhaustion, with your head still glowing from the heat of the day and blood throbbing in every fingertip.” He paused, seeming on the brink of fatigue from his description. “It’s the finest delusion I’ve succumbed to, because in a certain sense you have to delude yourself. The men call it ‘Russian fever’ but that’s a clumsy, feeble expression.”

“I’ve used the term myself,” I said, somewhat embarrassed by the admission.

“It’s something like this: When you see the world in all its enchanting beauty, you’re sometimes reluctant to concede that the other side of the coin exists. The antithesis exists here, as it does everywhere, if only you open your eyes to it. But here the antithesis is accentuated by war to such an extent that a weak person sometimes can’t endure it.”

We stepped across the rivulet and walked into a field filled with tall grasses. We had traveled for about ten minutes, when we came to a Russian cross sticking out of the ground. “This is where we buried him,” Hans said. “He was probably a good man, a Christian man, with a family and children. No one will ever know because he will lie here until the end of time.” He looked up from the grave toward the broad steppe, the grass swaying in the wind, and a tear rolled down his cheek. “So, you intoxicate yourself. You see only one side in all its splendor and glory.”

As I watched, he bowed his head and said a silent prayer. A wave, like an electric charge, prickled up my skin, a sense of joy akin to ecstasy washed over me, unlike any feeling I had experienced before. The sensation jolted me so much that I leaned against him.

Flushed from their feeding by an unseen visitor, a flock of gray-and-black jackdaws flew over our heads, cawing their shrill cry. A burst of sunlight lit the grave and then was consumed by the murky clouds as quickly as it had appeared.

Hans moved away from me, his hands clutched by his sides. “I don’t know you … I shouldn’t be talking of such things … Alex likes you and trusts you.”

I didn’t know what to say. What was he offering me—friendship, something more? Was he testing me, in slow steps, to see if I could be trusted? His face flushed almost to the point of red-hot anger. Whatever he carried inside was eating him up, although I got the sense that such an intimate display of passion was a rarity.

“Our days and nights are ruled by those who would commit evil and immoral acts,” I responded, attempting to placate him. “We can only do what’s right and offer praise and support when it’s deserved and condemnation when it’s justified. We must be strong in the face of moral corruption.”

“The Reich must be condemned.”

I stepped back, stunned by his words, and took a deep breath as we stood near the grave. I agreed but was unwilling to say so to a man I barely knew. “That thought must remain between you and me. You should not repeat it to anyone else.”

“This is why I fight—not for Germany, but for all men.”

I squeezed his hand and he smiled. We left the grave and proceeded back to camp, saying little as we walked. The overcast sky, except for a few sparkling breaks of sun, held fast through the afternoon and portended a bleak and dreary fall. That evening, as I sat in the dark with Greta, I recalled Hans’s words, and the bleak grave and the cawing jackdaws appeared in my head. Feeling a bit light-headed, I was overwhelmed by contrasting thoughts of a hopeful peace and a long war filled with death and destruction. I didn’t sleep well for several nights.

Alex recovered but Hans exhibited symptoms similar to diphtheria that put him in bed for several days. Alex withdrew a bit after his illness—not that he was unfriendly—but he, like Hans, seemed to be carrying an increasing weight on his shoulders. Our work kept us busy when the trucks and wagons rolled in carrying their cargo of dying and wounded men.

One late September morning, I decided to take advantage of some free time. I bundled up and walked along the dirt road leading to Sina’s. About halfway there, I reached a path, turning into a field alongside the birch forest, which had been cut into the tall grasses by trucks. Large puddles were scattered along its route, but the trail fueled my curiosity and I welcomed a change of scenery from my usual walk southward.

I had never been down it; in fact, it had escaped my attention. The vegetation lay crushed and dead under the weight of the tires while the brown and green stalks swayed in the air on each side; the earth was tamped hard in spots like rock, but spongy in other places.

The wind had picked up overnight as the first breath of winter poured in from the north. The small patches of sunlight on my shoulders did little to warm me, and I tried as best I could to stay out of the shade. The muddy tracks kept me sidestepping in and out of the shadows.

The birch branches, holding leaves that had turned from gold to a reddish purple, shuddered and bent in the gusts as their branches knocked against each other, and if not for the gale, the forest would have been silent. The path turned into a section of woods that had been cleared of trees. My senses sharpened in the gloom as the sound of an engine took me by surprise.

The engine revved behind me and tires spun in the mud. There were no Verboten signs at the beginning of the trail, no posted reason for me not to be here, but instinct told me to keep out of sight. The ground squished underneath my shoes as I knelt behind several trees that had been chopped down and piled upon one another. Through a narrow opening between the logs, I spotted a large truck, open in the back, with the black-and-white iron cross on its doors. About twenty people, surrounded by four armed SS guards and their commander, huddled against the wood panels that held them in back. The people were easy to identify as Russian by their attire; and, to my deepening horror, I recognized the faces of Sina and her two children, Dimitri and Anna.

The truck sped past me at a fast clip, bouncing over the rough path, splashing muddy water in its wake and coating the surrounding trees with the sloppy mix. As soon as the vehicle disappeared around a curve, I dashed back to the path in pursuit until I found a suitable hiding place nestled in a thick grove of trees. I had to see what was happening to Sina and her children.

The truck, its human cargo shuddering like tenpins as the brakes screeched, came to a halt near a shallow ravine within the forest. After that, my mind became foggy, hazy, in a scene that played out before me like a film in slow motion.

SS guards open the wooden gate on the back, one of them so kind as to even help an older woman wrapped in her flannel coat and kerchief to the wet ground. Russian men, mostly older with gray beards and long hair, some in work clothes, some in what look like pajamas, join the line of captives. Children look at their mothers with wide eyes, while grasping at coat sleeves as they totter along in small, hurried steps. The SS herd them along like cattle, shoving their machine gun barrels into the prisoners’ backs. The wood, silent, without song, without air, is claimed by the cold hand of Death.

The SS line them up between the two hillocks, the men with their hands clasped behind their necks, the women with heads bowed, the children, their eyes flashing between their guards and their mothers. Twenty or more here to die like animals led to slaughter.

“Scum. Subhuman.” The SS taunt them from their superior position atop the hill.

A song floats on the air, the one that Sina played in her home for Alex and me, and one by one the others join in until it fills the air with its melancholy melody.

A man shouts, “Quiet, pigs,” while the Commander counts down—four, three, two, one—then four SS armed with machine guns fire at once, a terrible volley of bullets, spent casings flashing copper in the air, smoke searing the air gray and black.

They fall like limp dolls to the ground, holes exploded in flesh, the exiting bullets striking in watery puffs against the damp earth, the prisoners’ blood turning dark on their coats and shirts.

I want to scream but no sound comes from my mouth. Horror. Blood, much more blood than I’d ever seen on the operating table, or on the gurneys as men die. Sina is spread-eagled on the ground, Dimitri and Anna, also dead, clutching her coat.

My hands rushed to my mouth to stop a scream as I fell back against a tree. Any uttered word, the fact that I’ve seen the unbelievable, could mean my death. I ran from my hiding place, loping along the path, hoping that the truck wouldn’t bear down upon me, fear punching me with adrenaline. I would be at peace if I were dead—after what my eyes had seen, I didn’t know if I would rest again. Then, I questioned what I had seen. Was it just an illusion caused by a fevered mind?

Soon I came to the dirt road and collapsed in tears near the path. When I was able to walk again, I discovered another horror. On the southern horizon a fire burned, sending black smoke spiraling into the sky. Sina’s house was engulfed in flames.

I wiped my eyes and staggered back to camp, like a woman overcome with sickness, unsure what to say or do. The truck caught up to me and slowed until one of the Wehrmacht drivers greeted me with a wave. The grim SS guards and the Commander in the back of the truck stared at me while they smoked their cigarettes, white stubs clenched between gritted teeth.

When I reached camp, I didn’t want to talk to anyone and kept my distance from Alex, Hans, and Greta.

After a sleepless night, I assisted a doctor the next day with a soldier who died on the table from a horrible chest wound. His last words to me as the doctor deserted him were, “Tell my parents I love them.”

My heart ached for the solider and for the slaughtered Russians who had died because a tyrant had deemed them unworthy of life. I was a Russian, too, but my family and I had been of service to Germany and in fact were accepted as Germans—but how long would that last?

Grief dragged me down for days before finally transforming into a growing rage against the man who had spawned the horrible crime I had witnessed—Adolf Hitler.

Hans was only half-right in his assessment that the Reich needed to be condemned. The Reich needed to be destroyed. The thought thrilled and horrified me at the same time.

CHAPTER 2

I never told anyone about what I had seen in the birch forest. I tried to wipe the barbarous crime from my memory if only to keep from going mad. A slip of the tongue, even to men I trusted, like Alex and Hans, might end in disaster. The SS guards and their commanding officer in the back of the empty truck occupied my thoughts like an ever-present, insidious disease. Their blank, white faces hovered like death heads over me.