A Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain I

2. The Guild Hall of the town, called by them the Moot Hall; to which is annex’d the town goal.

3. The Work-house, being lately enlarg’d, and to which belongs a corporation, or a body of the inhabitants, consisting of sixty persons incorporated by Act of Parliament anno 1698, for taking care of the poor: They are incorporated by the name and title of The Governor, Deputy Governor, Assistants, and Guardians, of the Poor of the Town of Colchester. They are in number eight and forty; to whom are added the mayor and aldermen for the time being, who are always guardians by the same Charter: These make the number of sixty, as above.

There is also a grammar free-school, with a good allowance to the master, who is chosen by the town.

4. The Castle of Colchester is now become only a monument shewing the antiquity of the place, it being built as the walls of the town also are, with Roman bricks; and the Roman coins dug up here, and ploughed up in the fields adjoining, confirm it. The inhabitants boast much, that Helena, the mother of Constantine the Great, first Christian Emperor of the Romans, was born there; and it may be so for ought we know; I only observe what Mr. Camden says of the castle of Colchester, viz. «In the middle of this city stands a castle ready to fall with age».[1]

Tho’ this castle has stood an hundred and twenty years from the time Mr. Camden wrote that account, and it is not fallen yet; nor will another hundred and twenty years, I believe, make it look one jot the older: And it was observable, that in the late siege of this town, a cannon shot, which the besiegers made at this old castle, were so far from making it fall, that they made little or no impression upon it; for which reason, it seems, and because the garrison made no great use of it against the besiegers, they fir’d no more at it.

There are two CHARITY SCHOOLS set up here, and carried on by a generous subscription, with very good success.

The title of Colchester is in the family of Earl Rivers; and the eldest son of that family, is called Lord Colchester; tho’, as I understand, the title is not settled by the creation, to the eldest son, till he enjoys the title of Earl with it; but that the other is by the courtesy of England; however this I take ad referendum.

Harwich and SuffolkFrom Colchester, I took another step down to the coast, the land running out a great way into the sea, south, and S. E. makes that promontory of land called the Nase, and well known to sea-men, using the northern trade. Here one sees a sea open as an ocean, without any opposite shore, tho’ it be no more than the mouth of the Thames. This point call’d the Nase, and the N. E. point of Kent, near Margate, call’d the North Foreland, making (what they call) the mouth of the river, and the port of London, tho’ it be here above 60 miles over.

At Walton, under the Nase, they find on the shoar, copperas-stone in great quantities; and there are several large works call’d Copperas Houses, where they make it with great expence.

On this promontory is a new sea mark, erected by the Trinity-House men, and at the publick expence, being a round brick tower, near 80 foot high. The sea gains so much upon the land here, by the continual winds at S. W. that within the memory of some of the inhabitants there, they have lost above 30 acres of land in one place.

From hence we go back into the country about four miles, because of the creeks which lie between; and then turning east again, come to Harwich, on the utmost eastern point of this large country.

Harwich is a town so well known, and so perfectly describ’d by many writers, I need say little of it: ’Tis strong by situation, and may be made more so by art. But ’tis many years since the Government of England have had any occasion to fortify towns to the landward; ’tis enough that the harbour or road, which is one of the best and securest in England, is cover’d at the entrance by a strong fort, and a battery of guns to the seaward, just as at Tilbury, and which sufficiently defend the mouth of the river: And there is a particular felicity in this fortification, viz. That tho’ the entrance or opening of the river into the sea, is very wide, especially at high-water, at least two miles, if not three over; yet the channel, which is deep, and in which the ships must keep and come to the harbour, is narrow, and lies only on the side of the fort; so that all the ships which come in, or go out, must come close under the guns of the fort; that is to say, under the command of their shot.

The fort is on the Suffolk side of the bay, or entrance, but stands so far into the sea upon the point of a sand or shoal, which runs out toward the Essex side, as it were, laps over the mouth of that haven like a blind to it; and our surveyors of the country affirm it to be in the county of Essex. The making this place, which was formerly no other than a sand in the sea, solid enough for the foundation of so good a fortification, has not been done but by many years labour, often repairs, and an infinite expence of money, but ’tis now so firm, that nothing of storms and high tides, or such things, as make the sea dangerous to these kind of works, can affect it.

The harbour is of a vast extent; for, as two rivers empty themselves here, viz, Stour from Mainingtree, and the Orwel from Ipswich, the channels of both are large and deep, and safe for all weathers; so where they joyn they make a large bay or road, able to receive the biggest ships, and the greatest number that ever the world saw together; I mean, ships of war. In the old Dutch War, great use has been made of this harbour; and I have known that there has been 100 sail of men of war and their attendants, and between three and four hundred sail of collier ships, all in this harbour at a time, and yet none of them crowding, or riding in danger of one another.

Harwich is known for being the port where the packet-boats between England and Holland, go out and come in: The inhabitants are far from being fam’d for good usage to strangers, but on the contrary, are blamed for being extravagant in their reckonings, in the publick houses, which has not a little encourag’d the setting up of sloops, which they now call passage-boats, to Holland, to go directly from the river of Thames; this, tho’ it may be something the longer passage, yet as they are said to be more obliging to passengers, and more reasonable in the expence, and as some say also the vessels are better sea-boats, has been the reason why so many passengers do not go or come by the way of Harwich, as formerly were wont to do; insomuch, that the stage-coaches, between this place and London, which ordinarily went twice or three times a week, are now entirely laid down, and the passengers are left to hire coaches on purpose, take post-horses, or hire horses to Colchester, as they find most convenient.

The account of a petrifying quality in the earth here, tho’ some will have it to be in the water of a spring hard by, is very strange: They boast that their town is wall’d, and their streets pav’d with clay, and yet, that one is as strong, and the other as clean as those that are built or pav’d with stone: The fact is indeed true, for there is a sort of clay in the cliff, between the town and the beacon-hill adjoining, which when it falls down into the sea, where it is beaten with the waves and the weather, turns gradually into stone: but the chief reason assign’d, is from the water of a certain spring or well, which rising in the said cliff, runs down into the sea among those pieces of clay, and petrifies them as it runs, and the force of the sea often stirring, and perhaps, turning the lumps of clay, when storms of wind may give force enough to the water, causes them to harden every where alike; otherwise those which were not quite sunk in the water of the spring, would be petrify’d but in part. These stones are gathered up to pave the streets, and build the houses, and are indeed very hard: ’Tis also remarkable, that some of them taken up before they are thoroughly petrify’d, will, upon breaking them, appear to be hard as a stone without, and soft as clay in the middle; whereas others, that have layn a due time, shall be thorough stone to the center, and as exceeding hard within, as without: The same spring is said to turn wood into iron: But this I take to be no more or less than the quality, which as I mention’d of the shoar at the Ness, is found to be in much of the stone, all along this shoar, (viz.) Of the copperas kind; and ’tis certain, that the copperas stone (so call’d) is found in all that cliff, and even where the water of this spring has run; and I presume, that those who call the harden’ d pieces of wood, which they take out of this well by the name of iron, never try’d the quality of it with the fire or hammer; if they had, perhaps they would have given some other account of it.

On the promontory of land, which they ‘call Beacon-Hill, and which lies beyond, or behind the town, towards the sea, there is a light-house, to give the ships directions in their sailing by, as well as their coming into the harbour in the night. I shall take notice of these again all together, when I come to speak of the Society of Trinity House, as they are called, by whom they are all directed upon this coast.

This town was erected into a marquisate, in honour of the truly glorious family of Schomberg, the eldest son of Duke Schomberg, who landed with King William, being stiled Marquis of Harwich; but that family (in England at least) being extinct, the title dies also.

Harwich is a town of hurry and business, not much of gaiety and pleasure; yet the inhabitants seem warm in their nests, and some of them are very wealthy: There are not many (if any) gentlemen or families of note, either in the town, or very near it. They send two members to Parliament; the present are, Sir Peter Parker, and Humphrey Parsons, Esq.

And now being at the extremity of the county of Essex, of which I have given you some view, as to that side next the sea only; I shall break off this part of my letter, by telling you, that I will take the towns which lie more towards the center of the county, in my return by the north and west part only, that I may give you a few hints of some towns which were near me in my rout this way, and of which being so well known, there is but little to say.

On the road from London to Colchester, before I came into it at Witham, lie four good market-towns at equal distance from one another; namely, Rumford, noted for two markets, (viz.) one for calves and hogs, the other for corn and other provisions; most, if not all, bought up for London market. At the farther end of the town, in the middle of a stately park, stood Guldy Hall, vulgarly Giddy Hall, an antient seat of one Coke, sometime Lord-Mayor of London, but forfeited, on some occasion, to the Crown: It is since pull’d down to the ground, and there now stands a noble stately fabrick or mansion-house, built upon the spot by Sir John Eyles, a wealthy merchant of London, and chosen sub-governor of the South-Sea Company, immediately after the ruin of the former sub-governor and directors, whose overthrow makes the history of these times famous.

Brent-Wood and Ingarstone, and even Chelmsford itself, have very little to be said of them, but that they are large thoroughfair towns, full of good inns, and chiefly maintained by the excessive multitude of carriers and passengers, which are constantly passing this way to London, with droves of cattle, provisions, and manufactures for London.

The last of these towns is indeed the county-town, where the county jayl is kept, and where the assizes are very often held; it stands on the conflux of two rivers, the Chelmer, whence the town is called, and the Cann.

At Lees, or Lee’s Priory, as some call it, is to be seen an antient house, in the middle of a beautiful park, formerly the seat of the late Duke of Manchester, but since the death of the duke, it is sold to the Dutchess Dowager of Buckinghamshire; the present Duke of Manchester, retiring to his antient family seat at Kimbolton in Huntingdonshire, it being a much finer residence. His grace is lately married to a daughter of the Duke of Montague by a branch of the house of Marlborough.

Four market-towns fill up the rest of this part of the country; Dunmow, Braintre, Thaxted, and Coggshall; all noted for the manufacture of bays, as above, and for very little else, except I shall make the ladies laugh, at the famous old story of the Flitch of Bacon at Dunmow, which is this:

One Robert Fitz-Walter, a powerful baron in this county, in the time of Hen. III. on some merry occasion, which is not preserv’d in the rest of the story, instituted a custom in the priory here; That whatever married man did not repent of his being marry’d, or quarrel, or differ and dispute with his wife, within a year and a day after his marriage, and would swear to the truth of it, kneeling upon two hard pointed stones in the church yard, which stones he caus’d to be set up in the priory church-yard, for that purpose: The prior and convent, and as many of the town as would, to be present: such person should have a flitch of bacon.

I do not remember to have read, that any one ever came to demand it; nor do the people of the place pretend to say, of their own knowledge, that they remember any that did so; a long time ago several did demand it, as they say, but they know not who; neither is there any record of it; nor do they tell us, if it were now to be demanded, who is obliged to deliver the flitch of bacon, the priory being dissolved and gone.

The forest of Epping and Henalt, spreads a great part of this country still: I shall speak again of the former in my return from this circuit. Formerly, (’tis thought) these two forests took up all the west and south part of the county; but particularly we are assur’d, that it reach’d to the River Chelmer, and into Dengy Hundred; and from thence again west to Epping and Waltham, where it continues to be a forest still.

Probably this forest of Epping has been a wild or forest ever since this island was inhabited, and may shew us, in some parts of it, where enclosures and tillage has not broken in upon it, what the face of this island was before the Romans time; that is to say, before their landing in Britain.

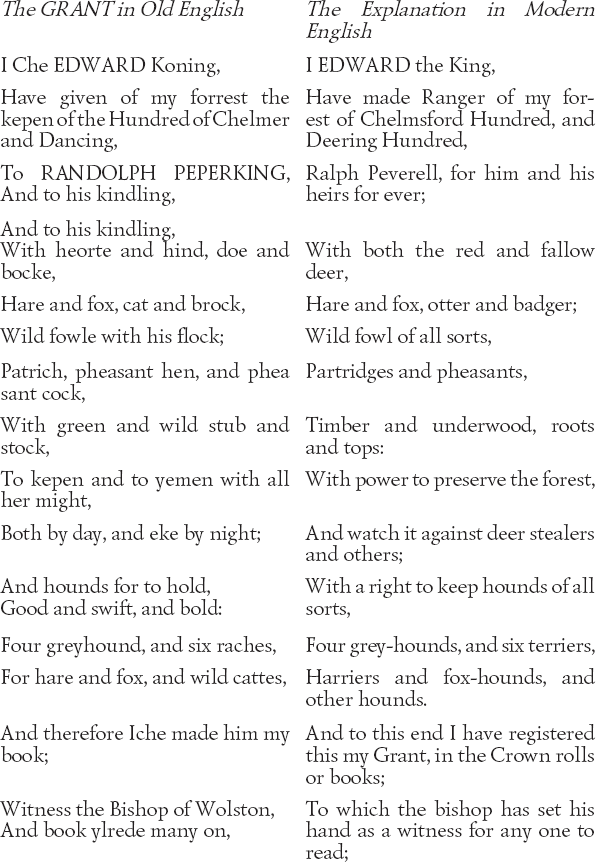

The constitution of this forest is best seen, I mean, as to the antiquity of it, by the merry grant of it from Edward the Confessor, before the Norman Conquest to Randolph Peperking, one of his favourites, who was after called Peverell, and whose name remains still in several villages in this county; as particularly that of Hatfield Peverell, in the road from Chelmsford to Witham, which is suppos’d to be originally a park, which they call’d a field in those days; and Hartfield may be as much as to say a park for deer; for the stags were in those days called harts; so that this was neither more nor less than Randolph Peperking’s Hartfield; that is to say, Ralph Peverell’s deer-park.

N. B. This Ralph Randolph, or Ralph Peverell (call him as you please) had, it seems, a most beautiful lady to his wife, who was daughter of Ingelrick, one of Edward the Confessor’s noblemen: He had two sons by her, William Peverell, a fam’d soldier, and Lord or Governor of Dover Castle; which he surrender’d to William the Conqueror, after the Battle of Sussex; and Pain Peverell, his youngest, who was Lord of Cambridge: When the eldest son delivered up the castle, the lady his mother, above nam’d, who was the celebrated beauty of the age, was it seems there; and the Conqueror fell in love with her, and whether by force, or by consent, took her away, and she became his mistress, or what else you please to call it: By her he had a son, who was call’d William, after the Conqueror’s Christian name, but retain’d the name of Peverell, and was afterwards created by the Conqueror, Lord of Nottingham.

This lady afterwards, as is supposed, by way of penance, for her yielding to the Conqueror, founded a nunnery at the village of Hatfield-Peverell, mentioned above, and there she lies buried in the chapel of it, which is now the parish-church, where her memory is preserv’d by a tomb-stone under one of the windows.

Thus we have several towns, where any antient parks have been plac’d, call’d by the name of Hatfield on that very account.

As Hatfield Broad Oak in this county, Bishop’s Hatfield in Hertfordshire, and several others.

But I return to King Edward’s merry way, as I call it, of granting this forest to this Ralph Peperking, which I find in the antient records, in the very words it was pass’d in, as follows: Take my explanations with it, for the sake of those that are not us’d to the antient English.

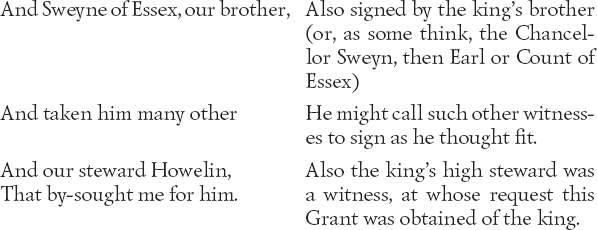

He might call such other witnesses to sign as he thought fit.

Also the king’s high steward was a witness, at whose request this Grant was obtained of the king.

There are many gentlemen’s seats on this side the county, and a great assemblee set up at New-Hall, near this town, much resorted to by the neighbouring gentry. I shall next proceed to the county of Suffolk, as my first design directed me to do.

From Harwich therefore, having a mind to view the harbour, I sent my horses round by Maningtree, where there is a timber bridge over the Stour, called Cataway Bridge, and took a boat up the River Orwell, for Ipswich; a traveller will hardly understand me, especially a seaman, when I speak of the River Stour and the River Orwell at Harwich, for they know them by no other names than those of Maningtre-Water, and Ipswich-Water; so while I am on salt water, I must speak as those who use the sea may understand me, and when I am up in the country among the in-land towns again, I shall call them out of their names no more.

It is twelve miles from Harwich up the water to Ipswich: Before I come to the town, I must say something of it, because speaking of the river requires it: In former times, that is to say, since the writer of this remembers the place very well, and particularly just before the late Dutch Wars, Ipswich was a town of very good business; particularly it was the greatest: town in England for large colliers or coal-ships, employed between New Castle and London: Also they built the biggest: ships and the best, for the said fetching of coals of any that were employed in that trade: They built also there so prodigious strong, that it was an ordinary thing for an Ipswich collier, if no disaster happened to him, to reign (as seamen call it) forty or fifty years, and more.

In the town of Ipswich the masters of these ships generally dwelt, and there were, as they then told me, above a hundred sail of them, belonging to the town at one time, the least of which carried fifteen-score, as they compute it, that is, 300 chaldron of coals; this was about the year 1668 (when I first knew the place). This made the town be at that time so populous, for those masters, as they had good ships at sea, so they had large families, who liv’d plentifully, and in very good houses in the town, and several streets were chiefly inhabited by such.

The loss or decay of this trade, accounts for the present pretended decay of the town of Ipswich, of which I shall speak more presently: The ships wore out, the masters died off, the trade took a new turn; Dutch fly boats taken in the war, and made free ships by Act of Parliament, thrust themselves into the coal-trade for the interest of the captors, such as the Yarmouth and London merchants, and others; and the Ipswich men dropt gradually out of it, being discouraged by those Dutch flyboats: These Dutch vessels which cost nothing but the caption, were bought cheap, carried great burthens, and the Ipswich building fell off for want of price, and so the trade decay’d, and the town with it; I believe this will be own’d for the true beginning of their decay, if I must allow it to be call’d a decay.

But to return to my passage up the river. In the winter time those great collier-ships, abovemention’d, are always laid up, as they call it: That is to say, the coal trade abates at London, the citizens are generally furnish’d, their stores taken in, and the demand is over; so that the great ships, the northern seas and coast being also dangerous, the nights long, and the voyage hazardous, go to sea no more, but lie by, the ships are unrigg’d, the sails, &c. carry’d a shore, the top-masts struck, and they ride moor’d in the river, under the advantages and security of sound ground, and a high woody shore, where they lie as safe as in a wet dock; and it was a very agreeable sight to see, perhaps two hundred sail of ships, of all sizes lye in that posture every winter: All this while, which was usually from Michaelmas to Lady Day, The masters liv’d calm and secure with their families in Ipswich; and enjoying plentifully, what in the summer they got laboriously at sea, and this made the town of Ipswich very populous in the winter; for as the masters, so most of the men, especially their mates, boatswains, carpenters, &c. were of the same place, and liv’d in their proportions, just as the masters did; so that in the winter there might be perhaps a thousand men in the town more than in the summer, and perhaps a greater number.

To justify what I advance here, that this town was formerly very full of people, I ask leave to refer to the account of Mr. Camden, and what it was in his time, his words are these.

«Ipswich has a commodious harbour, has been fortified with a ditch and rampart, has a great trade, and is very populous; being adorned with fourteen churches, and large private buildings».

This confirms what I have mentioned of the former state of this town; but the present state is my proper work; I therefore return to my voyage up the river.

The sight of these ships thus laid up in the river, as I have said, was very agreeable to me in my passage from Harwich, about five and thirty years before the present journey; and it was in its proportion equally melancholly to hear, that there were now scarce 40 sail of good colliers that belonged to the whole town.

In a creek in this river call’d Lavington-Creek we saw at low water, such shoals, or hills rather, of muscles that great boats might have loaded with them, and no miss have been made of them. Near this creek Sir Samuel Barnadiston had a very fine seat, as also a decoy for wild ducks, and a very noble estate; but it is divided into many branches since the death of the antient possessor; but I proceed to the town, which is the first in the county of Suffolk of any note this way.

Ipswich is seated, at the distance of 12 miles from Harwich, upon the edge of the river, which taking a short turn to the west, the town forms, there, a kind of semi-circle, or half moon upon the bank of the river: It is very remarkable, that tho’ ships of 500 tun may upon a spring tide come up very near this town, and many ships of that burthen have been built there; yet the river is not navigable any farther than the town itself, or but very little; no not for the smallest boats, nor does the tide, which rises sometimes 13 or 14 foot, and gives them 24 foot water very near the town, flow much farther up the river than the town, or not so much as to make it worth speaking of.

He took little notice of the town, or at least of that part of Ipswich, who published in his wild observations on it, that ships of 200[2] tun are built there: I affirm, that I have seen a ship of 400 tun launch’d at the building-yard, close to the town; and I appeal to the Ipswich colliers (those few that remain) belonging to this town, if several of them carrying seventeen score of coals, which must be upward of 400 tun, have not formerly been built here; but superficial observers, must be superficial writers, if they write at all; and to this day, at John’s Ness, within a mile and half of the town it self, ships of any burthen may be built and launched even at neap tides.

I am much mistaken too, if since the Revolution, some very good ships have not been built at this town, and particularly the Melford or Milford-gally, a ship of 40 guns; as the Greyhound frigate, a man of war of 36 to 40 guns, was at John’s Ness. But what is this towards lessening the town of Ipswich, any more than it would be to say, they do not build men of war, or East-India ships, or ships of 500 tun burthen, at St. Catherines, or at Battle-Bridge in the Thames? when we know that a mile or two lower, (viz.) at Radcliffe, Limehouse, or Deptford, they build ships of 1000 tun, and might build first-rate men of war too, if there was occasion; and the like might be done in this river of Ipswich, within about two or three miles of the town; so that it would not be at all an out-of-the-way speaking to say, such a ship was built at Ipswich, any more than it is to say, as they do, that the Royal Prince, the great ship lately built for the South-Sea Company, was London built, because she was built at Lime-house.