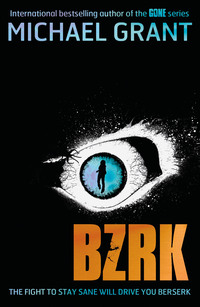

BZRK

Stone fell through in a tangle with his father. The two of them hit Kelly’s seat and crashed into the instrument panel, smashed into the windshield. Pain shot through Stone’s knees, his elbow, his shoulder. Didn’t matter because now the green field was so near. Zooming up at him.

A flash of Kelly’s face, eyes blank, mouth bleeding from hitting the instrument panel, short-cut gray hair matted, staring hard in horror. Staring at something maybe only she could see.

A flash of the stands full of people.

His father flailing, legs tangling, something broken, head hanging the wrong way, too confused to . . .

“Dad!” A sob, not a shout.

Stone pushed himself back from the instrument panel and somehow found the stick with his right hand and pulled hard.

Kelly turned to look at him. Like Stone’s action was puzzling to her. Like she was amazed to find him there. With dreamy slowness she reached for the stick.

The three of them tangled together in a heap and the field rushing up at them. So fast.

Way too fast.

And Stone knew it.

But he pulled back on the stick and yelled, “Dad!” for no reason because there wasn’t anything Stone could do but look at him with eyes full of horror and so sad; so, so sad.

“Dad!”

The jet began to respond. The nose started to come up. The stadium seats looked like they were falling away, and now the top of the stadium, the upper rim was in view.

And some remote, still-functioning part of Stone’s brain realized they were actually inside the stadium. A jet. Inside a bowl. Climbing toward safety.

Faces. Stone could see thousands of faces staring up at him and so close now he could see the expressions of horror and see the eyes and open mouths and drinks being spilled, legs tripping as they tried to run away.

He saw team shirts.

A redheaded kid.

A mother pulling her baby close.

An old guy making the sign of the cross, like he was doing it in slow motion.

“Dad.”

Then the jet flipped. Up was down.

The jet was moving very fast. But not quite the speed of sound. Not quite the speed of sound, so the crunch of the aluminium nose hitting bodies and seats and concrete did reach Stone’s ears.

But before his brain could register the sound, Stone’s honest brow and strong nose and broad shoulders and his brain and ears, too, were smashed to jelly.

Stone was instantly dead, so he did not see that his father’s body was cut in two as it blew through the split side of the cockpit.

He did not see that a section of Grey’s shattered-melon head flew clear, bits of gray-and-pink matter falling away, a trail of brain.

A small piece—no bigger than a baby’s fist—of one of the great minds of modern times landed in a paper cup of Coors Light and sank into the foam.

Then the explosion.

THREE

Sadie McLure didn’t see the jet until it was far too late.

The boy she was with—Tony—was not a boyfriend. Not really. But maybe. If he grew up a little. If he got past being weird about the fact that his father was just a department manager at McLure Industries. That he lived in a house half the size of the McLure home’s garage.

“Sorry about these seats,” Tony said for, oh, about the tenth time. “I thought I might get access to my buddy’s skybox, but . . .”

Yeah, that was the problem for Sadie: not being in a skybox while she watched a game she didn’t understand or like.

Until Tony had brought it up, Sadie had had no idea what a skybox was.

So not the most important thing in the world, that disparity in income. If she limited herself to dating the kids of other billionaires, she wasn’t going to have much to choose from.

“I enjoy mixing with the common people,” Sadie said.

He looked startled.

“That was a joke,” she said. Then, when he didn’t smile, she added, “Kidding.”

Try to be nice, she told herself.

Try to be more flexible.

Sure, why not a football game? Maybe it would be fun. Unless of course it involved some otherwise perfectly attractive and intelligent boy apologizing for his five-year-old Toyota and his jacket, which was just . . . she didn’t even remember what brand, but he seemed to think it wasn’t the right brand.

If there was a downside to being well-off—and there weren’t many—it was that people assumed you must be a snob. And no amount of behaving normally could change some people’s mind.

“Have a nacho,” Sadie said, and offered him the cardboard tray.

“They’re pretty awful, aren’t they?” he replied. “Not exactly caviar.”

“Yeah, well, I’ve already had my caviar for the day,” Sadie said. And this time she didn’t bother to explain that that was a joke. Instead she just scooped up a jalapeño and popped a chip in her mouth and munched it gloomily.

This was going to be a long date.

Sadie could be described as a series of averages that added up to something not even slightly average. She was of average height and average weight. But she had a way of seeming far larger when she was determined or angry.

She was of average beauty. Unless she was flirting or wanted to be noticed by a guy, and then, so very much not average. She had the ability to go from, “Yeah, she’s kinda hot,” to “Oh my God, my heart just stopped,” simply by deciding to turn it on. Like a switch. She could aim her brown eyes and part her full lips and yes, right then, she could cause heart attacks.

And five minutes later be just a good-looking but not particularly noticeable girl.

At the moment she was not in heart-attack-causing mode. But she was getting to the point where she was starting to seem larger than she was. Intelligent, perceptive people knew this was dangerous. Tony was intelligent—she’d never have gone out with him otherwise—but he was not perceptive.

Jesus, Sadie wondered, probably under her breath, how long did these football games last? She felt as if it was entering its seventy-fifth hour.

She couldn’t just walk away, grab a cab, and go home; Tony would think it was some reflection on his lack of a diamond-encased phone or whatever.

Could she sneak a single earbud into the ear away from Tony? Would he notice? This would all go so much better with some music or an audiobook. Or maybe just white noise. Or maybe a beer to dull the dullness of it all.

“Clearly, I need a fake ID,” Sadie said, but too quietly for Tony to hear it over a load groan as a pass went sailing over the head of the receiver.

Sadie noticed the jet only after it had already started its too-sharp turn.

She didn’t recognize it as her father’s. Not at first. Grey wasn’t the kind of guy who would paint his plane with some company logo.

“That plane,” she said to Tony. She poked his arm to get his attention.

“What?”

“Look at it. Look what it’s doing.”

And the engine noise was wrong. Too loud. Too close.

A frozen moment for her brain to accept the impossible as the inevitable.

The jet would hit the stands. There was no stopping it. It was starting to pull up but way too late.

Sadie grabbed Tony’s shoulder. Not for comfort but to get him moving. “Tony. Run!”

Tony dug in his heels, scowled at her. Sadie was already moving and she plowed into him, knocked him over, skinned her knee right through her jeans as she tripped, but levered one foot beneath herself, stepped on Tony’s most excellent abs, pushed off, and leapt away.

The jet roared over her head, a sound like the end of the world, except that the next sound was louder still.

The impact buckled her knees as it earthquaked the stands.

Then, a beat. Not silence, just a little dip in the sound storm.

Then a new sound as tons of jet fuel ignited. A clap of thunder from a cloud not fifty feet away.

Fire.

Things flying through the air. Big foam fingers and the hands that had been waving them. Paper cups and popcorn and hot dogs and body parts, so many of those, tumbling missiles of gore flying through the air.

The blast wave so overwhelming, so irresistible, that she wouldn’t even realize for several minutes that she had been thrown thirty feet, tossed like a leaf before a leaf blower, to land on her back against a seat, the impact softened by the body of a little girl. Thrown away like a doll God was tired of playing with.

She felt the heat, like someone had opened a pizza oven inches from her face. And set off a hand grenade amid the cheese and pepperoni. The first inch of hair caught fire but was quickly extinguished as air rushed back to the vacuum of the explosion.

The next minutes passed in a sort of loud silence. She heard none of the cries. Could no longer hear the sounds of falling debris all around her. Could hear only the world’s loudest car alarm screaming in her brain, a siren that came not from outside her head but from inside.

Sadie rolled off the crushed form of the girl. On hands and knees between rows of seats. Something sticky squishing up through her fingers. Something red and white: bloody fat. Just a chunk of it, the size of a ham.

Should do something, should do something, her brain kept saying. But what? Run away? Scream?

Now she noticed that her left arm was turned in a direction arms didn’t turn. There was no pain, just the sight of bones—her own bones—sticking through the skin of her forearm. Thin white sticks jutting from a gash filled with raw hamburger.

She screamed. Probably. She couldn’t hear, but she felt her mouth stretch wide.

She stood up.

The fire was uphill from her in the stands, maybe thirty rows up. A tail fin was intact but being swiftly consumed by the oily fire. A pillar of thick, greasy smoke swirled and filled her nostrils with the stench of gas stations and barbecued meat before finding its upward path.

The main fire burned without much color to the flame.

Bodies burned yellow and orange.

Unless he had been blown clear, Tony’s would be one of them.

A fat man crawled away, pulling himself along on his elbows as fire crawled up his legs.

A boy, maybe ten, squatted beside his mother’s head.

Sadie realized a different scene of madness was going on behind her. She turned and saw a panicked crowd shoving and pushing like a herd of buffalo on the run from a lion.

But others weren’t running away but walking warily toward the carnage.

A man reached her and mouthed words at her. She touched her ear, and he seemed to get it. He looked at her broken arm and did an odd thing. He kissed his fingertips and touched them to her shoulder and moved along. Later it would seem strange. At that moment, no.

The tail of the plane was collapsing into the fire. Through the smoke Sadie just made out the registration number. She’d already known, somewhere down in her shocked brain. The number just confirmed it.

She wanted to believe something different. She wanted to believe her father and brother were not in that hell of fire and smoke. She wanted to believe that she was breathing something that was not the smoke of their roasted bodies. But it was hard to pretend. That took an effort she couldn’t muster, not just yet.

Right now she could believe that everyone, everywhere was dead. She could believe she was dead.

She looked down then and saw blood all down one trouser leg. Saturated denim. She stared at this, stupid, something going very wrong with her brain.

And then the stadium spun like a top and she fell.

*

“Good twitch,” the Bug Man whispered to himself, a quiet congratulations. Satisfaction at a victory. Not that it was much of one. However dramatic the end result might be in the macro, in the nano it had just been a long wire job. There’d been no bug-on-bug fighting. Just wiring, connecting image to action.

Anyone could have done it. But could they have done it as fast? Could they have wired the pilot’s brain in three days? And set her up to have a switch thrown as dramatically as this?

Hell, no.

He pulled his left hand from the glove. Then his right hand. They came free with a slight sucking sound. And with his hands freed he reached up and worked the tight helmet off his head.

Had to get that back strap adjusted right. It was still digging into the back of his head where the flesh of his neck met the close-cropped skull.

He was alone. There were larger rooms here on the fifty-ninth floor, and other twitcher stations with as many as four consoles. But the Bug Man rated a private space. Had he pressed the button for the motorized shade, he’d have seen the spire of the Chrysler Building a block to the west. No other twitcher had that view—not that he looked at it much. It wasn’t about the view, it was about having the right to it.

The room was simple, scarcely furnished aside from the console. The light was low, just a glow coming from the Peace Pearl aromatherapy candles in their elegant crystal dish. And the gray light of static on the monitor.

The Bug Man breathed.

A win. Take it, rack it, add it to the total.

He had known it was done when all eighteen nanobots—two fighters and sixteen frantic spinners—in the pilot had gone dark at the same instant.

Could anyone else have run eighteen bugs at once, with sixteen actively laying wire? Even platooned? No. No one. Let them try.

Still, just a wire job. Now if Vincent had been coming at him, yeah, then it would have been mythic. Could he have pulled that off? Maybe. No good would come from underestimating Vincent. Vincent had twitch.

The Bug Man glanced at the display panel, checking a readout from the telemetry off the lone “sneaker” nanobot on Sadie McLure’s date, hiding out up in his hair where no one would look. The readout showed a sudden spike from ambient temperature of twelve Celsius to sixty-three Celsius.

Fireball.

But not enough to kill the kid. Not enough to kill Sadie unless she was a lot closer to the explosion or else took some shrapnel.

Success. But not total. In all likelihood there was still a McLure.

Bug Man knew they’d all be waiting outside his room to congratulate him. He dreaded it because they would have the TV on and they’d be watching it all in lurid color, hanging on the tension-pitched voices of reporters in helicopters.

Bug Man didn’t like postmortems. It was enough to succeed. There was no point in wallowing in it and high-fiving and all the rest.

He wished he didn’t have to go out at all. But he needed to pee in the worst way.

He fumbled for his phone and stuffed the earbuds in. He found the music he was looking for.

When enemies start posing as friends, To keep you even closer in the end, The rooms turn to black. A kitchen knife is twisting in my back.

Bug Man had no friends. Not in this life. Not in this job. And plenty of people would put a knife in his back. Paranoia? Hah. Paranoia was common sense.

He pulled the hood of his sweatshirt over his head and, with a deep, bracing breath, opened the door.

Sure enough, Jindal was waiting with a high-five. Jindal was . . . well, what was he, exactly? A sort of office manager for twitchers? He saw himself as being in some kind of position of authority. The twitchers saw him as the guy who made sure the fridge had plenty of Red Bull.

Thirty-five years old, grinning ingratiatingly at a sixteen-year-old kid in a hoodie. Sucking up. Even doing a little dance move, like he was trying to impress the Bug Man with a flash of ghetto. Bug Man was from Knightsbridge, a pricey neighborhood in London. He was not from the Bronx. But what did Jindal know? Any black face had to be ghetto.

“The damn signal repeater on the blimp went weak on me, Jindal,” Bug Man said, a little too loud over the music in his ears. “I was down to eighty percent.”

Let’s see if Jindal wanted to dance about a glitchy repeater. Bug Man pushed past him.

But Burnofsky was a different thing. Couldn’t really just blow off Burnofsky. He might be a sixty-year-old burnout with a six-day growth of white whiskers and a drunk’s chewed-up nose, but Burnofsky had game. No one was a better twitcher than Anthony Elder aka Bug Man, but if there was a close number two it was Burnofsky.

After all, he had created the game.

Bug Man pulled out one earbud. The band was going on about watching the company that you keep. Burnofsky was making that twisted, sneering face that was his most pleasant expression.

“S’matter, Bug? You don’t want to see the video?”

“Bugger off, Burnofsky. I need a slash.”

Burnofsky must have already been hitting the Thermos where he kept his chilled vodka. He grabbed Bug Man’s shoulder and spun him around. “Come on, kid. Don’t you want to see the macro? This is an accomplishment. A great moment for all of us.”

Bug Man knocked the old drunk’s hand away, but not before being exposed to a high-def visual of devastation. Looked like a camera angle from that same blimp, too steady to be a helicopter. Smoke and bodies.

Bug Man turned away. Not because it was too terrible to see, but because it was irrelevant. “I just play the game, old man.”

“The Twins will want to thank you,” Burnofsky taunted. “You going to tell them to ‘bugger off’, too? I mean, you struck a major blow today, kid. Grey McLure and his boy are charcoal briquettes. You’ve stepped up to the big times, Anthony: you’re a mass murderer now, up in the macro, not just shooting spiders down in the meat. And we’re all one step closer to a world of perfect peace, happiness, and universal brotherhood.”

“I just want to be one step closer to the loo, man,” Bug Man said.

“It’s called the restroom in this country, you little British bastard.”

He started to move away, but Burnofsky stepped suddenly closer, put his bloodless, papery-fleshed hands on Bug Man’s neck, pulled him close, and breathed eighty-proof fumes into his ear. “You’ll grow up some day, Anthony. You’ll know what you did.” He lowered his voice to a whisper. “And it will eat you alive.”

Bug Man shoved him back, but not so hard as to knock him down. “How stupid are you, Burnofsky?” Bug Man grinned and shook his head. He pointed a finger at his own temple. “I just rewired that pilot’s brain. You think I won’t rewire my own? You know, if I ever feel the need?”

That shut Burnofsky up. The old man took a step back, frowned, and waved his hand like he was trying to block the sight of Bug Man’s smooth face.

“The macro is all micro, old man. You drown your conscience in booze or whatever it is you smoke that makes you smell like roadkill . . .” He saw Burnofsky glance nervously back at Jindal. So: Burnofsky thought that was a secret, did he? Old fool. “You do what you have to do, Burnofsky. It’s not my business, is it? But I have a better way. Snip snip, wire wire. I mean, you know, if I ever get old and soft in the head like you. Now: I either go to the toilet or pee on your leg.”

FOUR

Sadie McLure had passed out in the ambulance on the way to the ER.

She’d awakened in bits and pieces, in flashes of light, and hovering faces, and tiled ceilings and fluorescent fixtures rushing by overhead. Images of green scrubs, masks, tubes, and shiny metal instruments.

Like a dream. Not a good dream.

Sharp, breathtaking pain from her arm when someone jostled it.

And with the scrubs came the black suits. Security. Protect the McLure. That was her now: the McLure.

A stab of pain that was not from any nerve ending, a stab like a cold knife wielded by her own soul.

Then muzzy relief flowed through her veins as the opiates arrived to take the edge off.

Sleep. And terrible nightmares of falling into an oozing mass of burning flesh. Like overcooked marshmallow. And it wasn’t her father or brother burning but her mother, who hadn’t burned, who had died in a bed like this one, her insides eaten by cancer.

Sadie woke. How much later? No way to know. There was no calendar or clock in the room. What there was was a man in a black suit, white shirt, black tie, and an earpiece. He was sitting in the chair, legs crossed, reading a graphic novel.

He would have a gun. He would also have a stun gun. And probably a second gun in an ankle holster.

Sadie’s body was one massive bruise. She did a quick inventory and decided, yes, every single inch of her hurt. Inside and outside, she hurt.

She was on her back, head slightly elevated, a needle taped to her right arm. A clear plastic bag hung beside the bed.

Her left arm was wrapped in hard plastic sheathing, bent into a lazy L and suspended from a wire.

Something had been inserted in her urethra. It hurt, but at the same time she had the feeling it had been there for a while.

“Who are you?” she asked. It sounded perfectly clear in her head, but she had the impression it came out as a whisper.

The man’s eyes flicked up from his book.

“Water,” Sadie gasped, suddenly overwhelmed by the sensation of thirst.

The man rose quickly. He came to the bed and pressed a button. The door opened within seconds, and two nurses came in. No, a nurse and a doctor, one was wearing a stethoscope.

“Water,” Sadie managed to say in a semicoherent voice.

“First we have to—” the doctor said.

“Water!” Sadie snapped. “First: water.”

The doctor took a step back. She would not be the first or last to take that step back.

The nurse had a drinking bottle with a bent straw. She let Sadie swallow a little. A blessing.

Nurses, Sadie remembered. That’s what her mother had said as she lay dying. Doctors can all go to hell; nurses go straight to heaven. Not that Birgid McLure took either heaven or hell literally.

Alone.

Sadie was alone. The realization scared her.

Just me, she thought.

She thought she might be crying, but she couldn’t feel tears, only the need to shed them.

A second guy in a black suit was in the room. Older. The corporate security chief. Sadie knew him. Should remember his name, but she didn’t. A third man, sleek in a very expensive striped suit, might as well have had “lawyer” tattooed on his forehead.

The corporation was swinging into action. Lawyers, security, all of it too damned late.

She had a stupid question to ask. Stupid in that she already knew the answer. “My Dad. And Stone.”

“Now isn’t the time,” the nurse said kindly.

“Dead,” the security chief answered.

The nurse shot him a dirty look.

“She’s my boss,” the man said flatly. “She’s McLure. She asks a question, I answer.”

The doctor was busy reading the chart. The nurse peered at Sadie, as if measuring her courage. She was Jamaican, maybe, judging from the accent. Or from one of those other islands where they do cool things to the English language.

She gave a slight shrug and let Sadie take another blessed, blessed sip of water.

“I need to know how soon I can move her,” the security chief said. Stern. That was his name. Something Stern. He had one of those faces that always looked as if he had just come from shaving. His tie was neat, but the collar was twisted a bit sideways around his neck. And although he was trying hard to look impassive, the corners of his mouth kept tugging downward. His eyes were red. He had cried.

“Move her?” the doctor yelped. “What are you talking about? She has a compound fracture of the ulna and radius, a concussion, internal bleeding—”

“Doctor,” Stern said. “I can’t keep her safe here. We have a place. Our own doctors, our own facilities. And air-tight security.”

“She needs an MRI. We need to see if there’s any brain damage.”

“We have an MRI machine,” the lawyer said, oozing confidence. A Harvard Law voice. A voice with which you were simply not allowed to argue. “I am Ms McLure’s temporary legal guardian, and her attorney. And I think Ms McLure would rather have our own doctors. And frankly, you and this hospital would rather not have the media camped outside twenty-four/seven.”