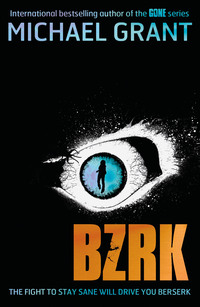

BZRK

Vincent wiped his mouth with his napkin.

He pushed back his chair.

V2 turned and ran from the four near and many farther-off nanobots. More were scurrying down the optic nerve. They weren’t a problem: using their four legs, the nanobots were slower than a biot. Only when they had a fairly smooth surface could the nanobots switch to their single wheel and outrun a biot.

Unfortunately the eyeball was perhaps the ultimate smooth surface.

V2 motored its legs at full speed. Back around the eyeball.

Vincent made his way slowly across the room toward Liselotte Osborne.

V2 waited until two of the nanobots were close enough to open fire. Their fléchettes ate a second leg away.

Vincent felt the echo of the pain in his own leg.

V2 sprayed sulfuric acid to left and right simultaneously. It wouldn’t kill the nanobots, but it would slow them, bog them down in puddles of melting flesh. And even on just four legs and dragging stumps he could maybe outrun the remaining nanobots.

Liselotte Osborne cried out suddenly.

“Oh! Oh!”

She pressed fingers over her eye.

“What is it?” one of the men asked, alarmed.

V2 was nearly crushed by the pressure, but Osborne’s fingers were to the north of it now, blocking the nanobots, and V2 had a clear path ahead.

“My eye! Something is in my eye. It’s rather painful.”

Vincent moved smoothly forward. “I’m a doctor; it could be a stroke. We need to lay this woman down.”

Funny how effective the phrase “I’m a doctor” can be.

Vincent eased Osborne from her chair and laid her flat on her back. He crouched over her, pushed her hand gently away from her face, and touched the surface of her eye with his finger.

Through V2’s optics he saw the massive wall of ridged flesh descending from the sky and ran to meet it.

Vincent’s free hand went into his pocket and came out, unnoticed, holding something black that might have been an expensive pen. He pressed the end of it against the base of Osborne’s skull.

V2 leapt onto the finger just as two nanobots emerged in the clear from the acid cloud.

Vincent pressed the clip on the pen and springs pushed three inches of tungsten-steel blade into Osborne’s medulla.

Vincent gave the blade a half-twist then pressed the clip again and withdrew what looked for all the world exactly like a nice Mont Blanc.

“This woman needs help,” Vincent said.

V2 ran up the length of his finger and dug barbs into his flesh.

Vincent stood up abruptly. “I’m going to summon an ambulance.” He turned and walked toward the exit.

It would be ten minutes before Liselotte Osborne’s friends and coworkers realized the doctor had not summoned anyone or anything at all. And by then the pool of blood beneath her head had grown quite large, and she was no longer complaining of pain in her eye.

SIX

Vincent was already in the air on his way back to the States, Nijinsky was relaxing with a drink at his London hotel and betting that Noah would show up for testing the next day, and Burnofsky was halfway through a bottle of vodka and thinking about his pipe, by the time Bug Man arrived home and found Jessica waiting for him.

She was standing three steps up on the stoop, bouncing a little to keep warm. She was two years older than he was, eighteen, from one of those North African countries, Ethiopia or Somalia, he could never remember which.

She had possibly the longest legs he had ever seen. She was taller than he was. And all parts of her were perfect. Crazy full lips and big, light brown eyes, and skin like warm silk, and hair in sort of loose, curly dreads that dangled down over her forehead and tickled Bug Man’s face when she was on top and kissing him.

“Hi, babe,” Bug Man said. “You must be freezing.”

“You’ll warm me up,” she teased, stepped down the stairs and held her arms open for him.

A kiss. A really good kiss, with steam coming from their lips and all her body heat transferring straight to his body, warming him through and through.

“You could have gone in to wait for me,” he said.

“Your mother doesn’t like me much,” Jessica said, not complaining.

He shrugged.

The Bug Man lived with his mother and her sister, Aunt Benicia, in Park Slope, up closer to Flatbush. The neighborhood was mostly white, well-off, infested by people in what was left of the publishing business. Writers and editors and so on. People who would go out of their way to smile at the black teenager with the strangely Asian eyes and the wide smile. They wanted him to know he was welcome. Despite, you know, being a black teenager in an upscale white neighborhood.

Bug Man didn’t live in one of the three-story townhomes the latte creatures spent small fortunes decorating. He and his little family had a nice three-bedroom, second floor, with too few windows and an inconvenient single bathroom. They’d lived there since moving to the States from London eight years ago. After Bug Man’s father had died of a stroke.

Aunt Benicia had some style, and Bug Man’s mother, Vallie Elder, had been careful investing the money from his father’s life insurance. And of course Bug Man kicked in a bit from his well-paying job in the city.

He was a video-game tester for the Armstrong Fancy Gifts Corporation. That’s what he told people. And how was anyone to know any different? Armstrong Fancy Gifts Corporation, you could Google it. They’d been in business since, like, the Civil War. You could go into one of their stores in malls or airport shopping areas. Bug Man could point out some of the games he had tested. There they were in the store or on the Web site.

Bug Man led Jessica inside. “It’s me,” he yelled. Preoccupied, his mother called back something from the direction of the kitchen. If Aunt Benicia was home, she said nothing.

“You want anything to eat?” Bug Man asked.

“Mmm-hmm,” Jessica said, breathing into his neck.

Oh yeah, that worked for Bug Man. That still made his heart miss a couple of beats. It had been a lot of complicated spinner work, hundreds of hours twitching his spinner-bots, identifying and cauterizing her inhibition centers. And then implanting images of the Bug Man in her visual memory and tying them with wire or pulse transmitters to her pleasure centers.

Exhausting work, since he had had to do it all on his own time. But so worth it. The girl was his. If Bug Man was honest, he’d admit he was maybe a six or seven on the looks scale. Jessica was off the scale. People on the street would see them together, and their jaws would drop and they’d get that “Life isn’t fair,” look, or maybe begin to form that “Man, what has that guy got going on?” question.

That was why his mum didn’t really like Jessica. She figured Jessica had to be after his money. As much as she loved her son, she knew better than to think it was his charm or his body.

Bug Man had an encrypted transmitter in his pocket, an innocuous key chain. He squeezed it and unlocked the door of his room.

With what he made at his job, the Bug Man’s room could have been a high-tech haven—plasma TVs and the latest electronic toys. But Bug Man got plenty of that at work. His room was a Zen sanctuary. A simple double bed, white sheets and a white headboard, the mattress centered on an ebony platform that seemed almost to float in the center of the room.

There was a cozy seating area with two black-leather-and-chrome armchairs angled in on a small tea table.

His desk, really just a simple table of elegant proportions, bore the weight of his somewhat old-fashioned computer—he couldn’t very well be completely cut off from the world—but was concealed from view by a mahogany windowpane shoji screen.

The real high tech in the room was all concealed from view. A sensor bar was imbedded in the edges of his door. It scanned the floor and doorjamb at a very high refresh rate, looking for anything at the nano level. The same technology was embedded in the window and in the walls around the electrical sockets.

The nanoscan technology wasn’t very good—lots of false positives. People who lived their whole lives in the macro didn’t know a tenth of what was crawling around down there in the floor dust.

And in any case, at the nano level the walls and baseboards were like sieves. But in Bug Man’s experience a twitcher would take the easy way in if possible—door, window, or riding on a biological. A biological being a human or a cat or dog, which explained why Bug Man didn’t let Aunt Benicia’s yappy little dog into his room.

The big weakness of nanobot technology was the need for a control station. Biots could be controlled brain to bot, but nanobots needed computer-assist and gamma-ray communication. Close and direct was best. Via repeaters if necessary, though the repeaters were notoriously glitchy.

Which meant that Bug Man took some risks being here in an insecure place. The alternative was having another twitcher running security on him day and night. That was not happening. Damned if he was letting one of those guys tap his optics and watch while he and Jessica were going at it.

Bug Man gave up enough for his job. He wasn’t giving up Jessica. She was the best thing that had ever happened to him. Those legs? Those lips? The things she did?

The work he had invested in her?

No, there were limits to what he’d do for the Twins. And there were limits to what the Twins could demand, because when it came down to battle in some pumping artery or up in someone’s brain, throwing down in desperate battle with Kerouac or Vincent—wait. He’d forgotten: Kerouac was out. Kind of a shame, really. Kerouac had serious game.

Well, as long as Vincent was still twitching and still undefeated, the Twins couldn’t say shit to Bug Man.

So, no, the Bug Man was not going to let some other newbie nanobot handler crawl up inside him while Jessica was crawling all over him. Sorry. Not happening.

Jessica shivered a little but shed her coat.

Bug Man locked the door.

“What do you want today, baby?” Bug Man asked, pulling her toward him.

“Whatever you want,” she whispered.

“Yeah. I thought you might say that.”

A soft trilling sound came from behind the shoji screen. Bug Man hesitated. “No,” he said.

The tone sounded again, louder.

“Hell, no,” he snapped.

“Don’t go,” Jessica said.

“Believe me when I say I don’t want to,” Bug Man said.

“Believe that. Don’t move. I mean, you can move, but mostly in a way that involves you having less clothing on. Let me just go see what this is.”

He walked a bit awkwardly from the bed to the concealed computer. A tiny red exclamation point pulsed in the upper-right corner of the screen. Bug Man cursed again. But he sat down in the chair, popped earbuds in, and tapped in a thirty-two-character code.

He’d expected to see Burnofsky’s ugly face. This was worse. Far worse. Because there on his screen were the Twins: the freak of nature comprising Charles and Benjamin Armstrong.

He masked the look of revulsion on his face. He’d met the Twins face-to-face on two occasions. This was an improvement—he couldn’t see that three-legged body—but not much of one. Not so long as he had to look at the nightmare that was their heads. The image barely fit on the screen. Two heads melted or melded or something into one.

“Anthony,” Charles Armstrong said. He was the one on the left. He usually did more of the talking.

“Yeah. I mean, good evening, sirs.”

“We are sorry to intrude. You deserve rest and relaxation after the important work you did earlier today. Truly, we are grateful, as all of humanity will someday be grateful.”

Bug Man’s mouth was dry. He had long since stopped giving a damn about the Armstrong Twins and their vision for humanity, all that Nexus Humanus bullshit. He was a twitcher, not an idealist. He loved the game. He loved the power. He loved the beautiful creature in his bed. The rest was just talk. But you couldn’t say that to Charles and Benjamin Armstrong. Not unless you had a much bigger pair than Anthony Elder happened to have, because Twofer—as the Twins were called behind their back—it, or they, or whatever was the correct way to say it, scared the hell out of the Bug Man.

“It seems that Vincent is in London,” Benjamin said. “As well as at least one other. We don’t know who.”

“Okay,” Bug Man said guardedly. The earbuds were crackling. Bad connection. He pulled them out and let the voice go to speaker. It wasn’t like Jessica would understand or care.

Charles smiled. When he did, the center eye—the eye they shared—swerved toward him.

Jesus. H. Christ.

“Time to press our advantage,” Charles said. “We are going ahead with our great plan, Anthony. Our latest intelligence is that the main target will be in New York.”

Bug Man rewarded his freak bosses with a sharp intake of breath. Jessica was suddenly forgotten. It had been all depression and frustration when word came that POTUS—the president of the United States—would skip the UN General Assembly and send the secretary of state instead.

“I thought she was Burnofsky’s target,” Bug Man said.

In order to shake their conjoined head Twofer had to move its, his, their entire upper body. The effect could have been comical. It wasn’t. “No, Anthony. Burnofsky has other duties as well. And as it happens, we’ve, for the moment, lost the pathway to your original target.”

Pathways were the macro means to a nano end. A nanobot couldn’t cross long distances. They didn’t fly. They didn’t go very fast in macro terms. In the nano a foot was a considerable distance. So pathways had to be found—carriers, people who would, wittingly or not, carry a nanobot to its target. For the kind of targets they had in mind the pathway had several steps, each step a person who would take the nanobots one stage closer.

Bug Man stared at that massive indented forehead. Tried not to look at that eye that so should not be there. But tried to imagine what was going on inside that creepy-ass head. People whispered that Twofer actually shared a part of their brain, just like they shared that center eye and, if legend was true, at least one other part as well.

The faces were framed against night sky and the green-lit spire of the Empire State Building, in what everyone called the Tulip. The Tulip was the top five stories of the Armstrong Building, what would have been floors sixty-three through sixty-seven, except that the pinnacle of the Armstrong Building was made of a polymer nanocomposite that was transparent looking out, and rose-colored frost for those looking in. The Twins lived their entire lives within that space, high above the city, invisible to outside eyes but wide open to spires and sky.

Bug Man’s original target had been the British prime minister. It had seemed right, what with Bug Man being British by birth.

But what had happened to the pathway? They’d had a clear one to the PM.

Anthony had been studying up on Prime Minister Bowen, looking through the man’s well-documented history, searching for the triggers he could pull in the old man’s brain. Oh, you like horses, do you, Mr Prime Minister? And you had a bad experience with your sister’s drowning? And your favorite chocolate bar is a Flake? All of that data was stored up in that wrinkly wad of goo called a brain.

A lot of wasted schoolwork, that, if someone else would be taking Bowen.

“What happened to the pathway?”

“As my brother mentioned, Vincent was in London.”

“It was not done at the nano,” Benjamin said, correctly guessing Bug Man’s thought. “Our friend Vincent did it the old-fashioned way. He stabbed her in the brain, Anthony. You should remember that. Because these are the lunatics we are fighting.” The Twins leaned forward, which put that third eye right up way too close, way too close, to the camera. The Bug Man leaned away.

“They are ruthless in a demonic cause,” Benjamin said, getting heated, getting worked up. “We would unite humanity! We would create the next human, the next step in evolution: a united human race! They fight to keep humanity enslaved to division, to hatred, to the loneliness of a false individuality.”

The sound of a fist pounding. The image wobbled.

“It begins as soon as you can come in,” Charles said. Calmer than his brother. “There’s a car waiting out front. You will come?” A simultaneous Twofer grin. “As a favor to us?”

“Yes, sirs,” he said. Because Bug Man didn’t want to try to guess what happened to people who refused to do “favors” for Twofer.

Bug Man emerged, serious and shaky, from behind the screen. Jessica was waiting.

“I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I’ve got to go. Big problem at work.”

Jessica pouted, and that was about enough to break Bug Man’s will, but no, he wasn’t ready to keep the Twins waiting.

“But I only need you for five minutes.”

The next five minutes, and all the rest of the conversation, was overheard by a single biot.

The biot—a specialized model adapted to picking up the kinds of large sound waves made by a vocal chord longer than their entire body—had spent six weeks inside Jessica’s right ear. Six weeks of earwax and near misses with Q-tips the size of blimps and earbuds blasting music that was sheer vibration.

Six weeks, weakening day by day, holding on despite everything, and now just days from death unless the biot could be taken out in a clean extraction.

In the coffee shop across the street Wilkes sat typing away on her laptop, pretending to be working on a novel, headphones on her ears.

Wilkes wasn’t the best twitcher—she wasn’t looking for a battle with Bug Man. But little Buggy hadn’t found her, had he? He had come close a few times, close enough that she could read the serial numbers of his nanobots and clearly see his creepy exploding head logo. But she had lain low. She had frozen in place. And the nanobots that might have killed her biot and driven Wilkes to madness had gone scurrying past.

Wilkes was not a great fighter down in the nano. She was much more capable in the macro, because when pushed, Wilkes was a little rage-o-holic. She affected a tough-girl style that wasn’t just style. She didn’t wear those big Doc Martens to look cool, she wore them to make her kicks count when she applied them.

Wilkes had a few interesting tattoos. Her right eye had dark flames painted downward, maybe more like shark’s teeth or the stylized teeth of a ripsaw. On the inside of her left arm she wore a QR-code tattoo. Shoot a picture of it with your phone and you’d be taken to a page that just had a picture of Wilkes’s raised middle finger and a circular logo that showed a Photoshopped pic of Wilkes stabbing a dragon in the eye.

There was a second QR-code tattoo in a, shall we say, less public location. It led to a different sort of page altogether.

She was a troubled teen, Wilkes was. Troubled, yes. And trouble, too.

But she could be patient when she had to be. Six weeks of this coffee shop, and a crappy little basement hole-in-the-wall apartment next door to Bug Man’s home.

In a weary voice Wilkes said, “Gotcha, Buggy. Got you good.”

ARTIFACT

To: Lear

From: Vincent

Summary:

Wilkes’s surveillance of Bug Man’s girlfriend has paid off.

1) Confirmed: Bug Man was the twitcher for the McLure hit.

2) Bug Man is being given a strategic as well as tactical role. This may indicate a serious problem with Burnofsky.

3) Confirmed: AFGC plans move at UN. POTUS is target #1. Other heads of state as well.

Recommend:

1) Given our need for biot resources, especially in view of the AFGC initiative and paralysis at McLure corporate, I recommend finalizing the Violet approach.

2) Accelerated training of new recruits.

Note: I am not Scipio.

SEVEN

Inside Sadie McLure’s head was a bubble. Sort of like a water balloon. Only it was the size of a grape and filled with blood.

It was thirty-three millimeters long, about an inch and a quarter. It was a brain aneurysm. Quite a large one. A place where an artery wall weakened and blood pressure formed the water balloon of death.

Because if it ever popped, blood would go gushing uncontrolled into the surrounding brain tissue. And Sadie would almost certainly die. And if not die, then lose parts of her brain, perhaps be left a vegetable.

There was an operation that could be done in some cases. But not in this case. Because the balloon inside Sadie’s head was buried down deep.

She had seen the CT scans, and the MRI scans, and even the fabulously detailed, nearly artistic digital subtraction angiography. That had involved shooting dye through an artery in her groin.

Ah, good times. Good times.

If she had stayed in the hospital, they’d have done a CT looking for bleeding. Then they’d have done an MRI to get a closer look at the aneurysm.

That’s when they would have noticed something unusual. A certain thickening of the tissue around the aneurysm.

So they’d have done the digital subtraction thing and then, yep, then they’d have had a pretty good picture of something that would make their hair stand up.

They’d have seen what looked like a pair of tiny little creatures, no bigger than dust mites, busily weaving and reweaving tiny strands of Teflon fiber to form a layer over the bulging, straining, grape-size water balloon.

They’d have seen Grey McLure’s biots, busy at the job of keeping his daughter alive.

Sadie could see them now as Dr Chattopadhyay—Dr Chat to her patient—swiveled the screen to show her.

“There are the biots in the first image.” She tapped the keyboard to change pictures. “And here they are half an hour later.”

“They haven’t moved.”

“Yes, they are immobile. Presumably dead.” Dr Chat was in her fifties, heavy, dark-skinned, skeptical of eye and immaculate in her lab coat over sari. “You know of course that I and my whole family mourn for your father and brother.”

Sadie nodded. She didn’t intend to be curt or dismissive. She just couldn’t hear any more condolences. She was suffocating in condolences and concern.

Over the last twenty-four hours she had absorbed the deaths. Absorbed, not coped with, accepted, gotten over, or properly mourned. Just absorbed. And somehow seeing those tiny dead biots was one step too far.

What her father had created was a revolution in medicine. It had taken him years. He had thrown more than a billion dollars into it, which had required him to buy back his own company from stockholders just so he could spend that kind of money without having to explain himself.

He had worked himself half to death, he and Sadie’s mother. Then, the cancer, and he was even more desperate to finish the work, to send his tiny minions in to kill cancer cells and save his wife.

The pressure he had endured.

But the biot project was too late for Sadie and Stone’s mother, Grey’s wife.

For three months after Birgid McLure’s death Grey was virtually invisible. He lived at work. And then . . . the miracle.

The biot. A biological creature, not a machine. A thing made of a grab bag of DNA bits and pieces. Spider, cobra, jellyfish. But above all, for the control mechanism that allowed a single mind to see through the eyes of a biot and run with a biot’s legs and cut with a biot’s blades, for that, human DNA.

The biot was not a robot. It was a limb. It was linked directly to the mind of its creator. It was a part of its creator.

Grey McLure’s biots had been injected as close to the aneurysm as was safe. They had set up a supply chain that ran through her ear canal to shuttle in the tiny Teflon fibers. And then they began to weave, a sort of macro-actual tiny, but micro-subjective huge, basket around the aneurysm.