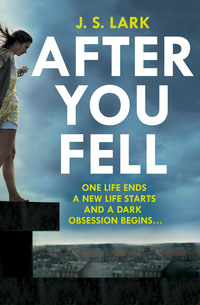

After You Fell

I look down at my phone and touch it to open the news story.

The parents of the woman who fell from a Swindon car park are calling for witnesses.

I touch the link as the train slows.

Louise’s parents have been on a local radio station asking for people to come forward if they saw Louise on the day she died.

The train draws into the station. The music player walks away.

I open Facebook on my phone and look at Robert Dowling’s account. His profile image is a picture of him and his wife. They must have been leaving to do that interview when I saw them. They still care about their daughter. She’s dead and they will not let her go. They’re the parents I dreamed of as a child.

An empty sensation swells inside me, just below my ribs, deep in my stomach. A space for love, that was supposed to have been filled by my parents. It is parent-shaped. Neither Simon nor Dan ever filled that gap. My parents left it empty. Instead of having love to warm me like a radiator, exuding a sense of safety from the inside out, there is a cold vacuum in me. A black hole, pulling at everything, dragging my consciousness back to the things I have missed out on because they went away.

At times in my life that black hole eats me alive.

If I had parents like Louise’s how different would my life have been?

My thumb slides over the screen on my phone, scrolling through happy family pictures.

There are lots of pictures of the blond children.

Why did Louise fall from that car park?

The friend button stares at me in the way Robert Dowling did through the car’s windscreen. I touch it to send a request. I want to help them.

‘How did the interview go?’ Simon hands me a pile of knives and forks.

This time of the evening, when Simon has just walked through the door, the house has the activity of a trout pond at feeding time, there is such a rush to get the tea on the table.

‘I like doing the cutlery.’ Liam grasps the sharp ends and pulls the knives and forks out of my hand.

‘Careful, you’ll cut yourself,’ Mim warns.

‘I can carry the plates.’ Kevin bounces over to take them from Mim. Then braces them on his forearms, to carry them safely.

‘Thank you,’ Mim acknowledges as the pile of china wobbles.

‘The interview, Helen …’ Simon pushes at me.

I glance over with no excuse left to avoid the conversation. ‘It went all right.’

‘I’m not sure you’re ready to go back to work, though. I think you should wait.’ He’s running cold water to fill a plastic jug to put on the table. ‘You don’t need to worry about getting back to work. There’s no hurry.’

I turn to the cupboard to fetch plastic cups for the children. He couldn’t have said anything better. ‘I’m not worried. If I get a job I wouldn’t start until January, for the spring term.’

‘Good. We like you staying here.’

The boys are climbing onto their chairs. They lift their knives and forks upright in an impatient gesture. I reach over and put down their cups. Simon walks around to fill their cups.

‘But I am excited about getting back to work.’ Just busy doing something else. ‘This just wasn’t the right job.’

Simon sits down as I turn to get three glasses.

Mim puts a dish full of steaming cottage pie on the table as I put down our glasses for Simon to fill.

Mim and Simon share a look that communicates something.

The smell of the cheese that has melted into the mashed potato stirs my appetite.

When I sit down, an image of the children from Robert Dowling’s Facebook posts comes into my head. An image of them sitting around a table. It is one of Louise’s memories. She can’t make me hear her words, but she sometimes succeeds in making me see her past.

What’s the conversation at their dinner table tonight? They must all miss Louise, and I know she misses them.

Her sadness pulls at me like the flow of an outgoing tide that drags all the sand out from around my feet, sucking at my legs and trying to pull me out with the tide. I am no-longer hungry.

Emotions and visions are connecting me to Louise with a slowly firming knot – like a lace being pulled as I walk, gradually tightening an accidental knot that’s formed itself in the place where a bow has been. If I want to untie it, I’ll struggle now.

Mim passes Simon the spoon to dish up.

‘Hold up your plate, Helen,’ he says.

I lift the plate so he can fill it. ‘Stop. That’s enough.’

He’s not looking at me but telling Mim about his day at work. I put my plate down. The serving spoon falls against the rim of the pot as she tells him something about her day too. There is nothing to be said about my day. I fill up my fork and blow on the steaming meat and potato to cool it.

I force myself to eat four mouthfuls, then set the knife and fork to rest on the edge of the plate and push the plate away by a couple of centimetres. ‘I’m not hungry tonight. I think I’m going to go to bed.’

Simon looks from Mim to me. ‘Did you do too much today? It was—’

‘I’m fine. I promise. Just tired. Everyone gets tired occasionally.’

A slight frown creases his forehead, making several rows of long thin lines. He looks about ten years younger than he is until the moment he frowns and those wrinkles show.

I take my plate away and scrape the leftovers into the bin. It’s a waste. The lid of the pedal bin falls with a sharp ring. When I turn around Simon is looking at me. I smile, widely, probably overdoing the happy show, walk over, bend down and wrap my arms around his neck. The movement makes the scar on my chest pull but it doesn’t hurt much. ‘I love you,’ I say quietly against his ear; they are words that are just for his ears. He pats my shoulder as I pull away.

‘Goodnight,’ I say to Mim.

I walk around the table and kiss Liam on the top of his head, then Kevin on the top of his head.

My laptop is in the living room. I stop to pick it up so I can take it upstairs. I’m going to bed to look up Robert Dowling’s interview. It will be on the iPlayer Radio.

‘Simon …’ Mim’s voice reaches from the kitchen behind me, with a tone of warning; the tone that comes before the boys get a ‘ten seconds to do something’ countdown.

‘Don’t,’ is his answer; a full stop that ends a conversation that never began, and then there is no sound except the scraping of cutlery on plates.

I listen to the interview in the dark, in bed, with an earphone in my left ear, my head sinking into the pillow. The cotton releases the smell of Mim’s lavender-scented washing conditioner. It is a smell of safety. My whole body calls this bed mine but it is Simon’s and Mim’s spare bed, for guests, not a permanent place for me.

I have no home.

Nowhere that I can call mine. I think it makes it worse that the only place I have ever thought of as mine is now Dan’s and his new woman’s. But I couldn’t be the one who kept the flat because I was too ill to live in it alone.

If I’d had parents, I would have had a home to always go back to. A home like Louise’s, with a flower bed full of scented roses, and parents who loved her. There’s that vacuum again.

The emotion in me is envy. It is my emotion. Louise had what I always wanted.

When the vacuum sucks everything away this is what’s left: darkness. Envy. Anger. Pain. These are the emotions that can take over when bipolar slips into what people call manic depression.

The Dowlings’ radio interview is eleven minutes long. They talk for four minutes then there is a break for a song and another seven minutes.

I want to help. I wish I had something I could say that would help. Their love for Louise flows in the cadence of their voices. There is a moment when Robert says something to his wife, Patricia. ‘I know, Pat, I feel that way too.’ I imagine him holding her hand as she makes a sound, a slight acknowledgement that says she is reassured.

An ache presses through my heart, as it makes itself heard, in a gentle rhythm as I listen to the Dowlings again.

Louise’s sadness becomes a lead weight in my chest and there’s a tension in my throat; she wants to cry.

If I were her, I would be crying.

I want to know love like that.

In Louise’s body, while she was alive, I think this heart would have clasped tight with love when she heard these voices.

The Dowlings mean everything to one another and Louise must have been enveloped in that love too.

When I was young, I imagined myself in a happy sitcom family. But Louise’s family are painting a new mental picture of what life would have been like with parents. What her life was like. What mine could have been like – still might be like.

I look up the one image of Louise that I have access to and play the recording from the beginning, listening for her voice inside me. I can’t hear the words but I hear her: a whisper that’s out of reach.

I want to hear her. I want to understand what she’s saying. I want to understand what she wants me to do.

Chapter 10

6 weeks and 1 day after the fall.

When I leave the railway station, a strong breeze sweeps at me like a broom trying to push me back through the sliding doors.

An answering shiver rattles through my body, up my spine and into my shoulders.

When I dressed this morning, I chose a thin jumper, not thick enough to keep out the cold. I haven’t mastered the forecasting skills required for being outside in the British weather, and the chill in the air is a reminder that in just over two weeks it will officially be autumn.

But perhaps the shiver came from the sense I have that Louise is watching me walking the streets of Swindon – a someone-has-just-walked-over-my-grave sort of shiver.

Her spirit feels more active today. Louder. My heart is pulsing hard and there is a hum of energy in my blood that is making her undeterminable whispers stronger. It is like having someone fidgeting impatiently in my body.

The crossing that is in front of me will take me to the shopping area.

There are tall buildings all around the station but the multi-storey car park is farther away.

Other people who disembarked from the 11.27 train cross the road beside me while the green walking man counts down. The knowing pace of the man in front of me leads me in the right direction, across paved pedestrian areas.

The shopping area is busier than I expected. It will be even busier in fifteen minutes when the office-workers spill out of the high buildings, like ants from an aggravated nest, to buy lunch.

A young boy who is close by complains to his mother. ‘Get in the pushchair!’ she yells, provoking a tirade of screams.

Blustery breezes stir up children. They want to run. Children in a playground are like birds when they play on a strong breeze. There is excitement and expectation in the air of a good breeze.

A young woman sweeps past on a skateboard, putting one foot down to push the skateboard on as she cuts in front of me. She weaves quickly through the people ahead. My gaze follows her until she disappears into the crowd. Then I see it.

The car park is a looming shadow stealing the sunlight from the street farther on; a concrete mass that peers over the top of the shops in the structure of a layer cake.

This is the street that Louise fell into.

At the top of the car park there is a wall. Somehow Louise fell over the top of that wall.

The sky is an innocent, denying blue today. Nothing happened up here, it tries to say.

But something did.

Picture after picture of this street and that car park are in my head. The images I have studied on my laptop in the last two days.

What happened, Louise?

I think she knows I have come here to find out. I think this is what she wants me to do.

The flow of people carries on into the town. A fast-running river of humanity.

I am looking for the narrow alley I have seen on Google Earth images that runs between two of the shops, to a pedestrian entrance at the side of the car park.

Three woman cross the pavement in front of me, from one shop to another. I stop to let them pass.

There is another skateboarder ahead, using a metal bicycle stand as an obstacle to perform tricks. The stand is outside a shop door that I have stared at in news articles.

It is the door.

The shop.

Louise fell onto this pavement, in that place.

I do not walk on. I can’t move. My feet are stone. The ground is thick mud to be waded through and my trainers are stuck in the sludge.

There is no mark, no rusty iron-looking bloodstain to say she was here. Nothing. It is as if the fall that ended her life, and began mine, did not happen. The sky, the car park and pavement all cry out. It was not me! Nothing happened here!

But something very wrong happened here. Women don’t just fall over car-park walls.

This heart must have pumped the blood through her broken body while she lay here.

The alley I have been looking for is on the left: a metre-and-half-wide rabbit-hole.

The block paving carpeting most of the town centre doesn’t reach into the shadowy environment of the alley. This area of Swindon, that’s hiding behind the shops, must have been built in the 1970s concrete explosion.

No one else is walking through here but there’s a man sitting on the floor a few metres ahead, on a filthy sleeping bag, with a dog; both have their legs stretched out. The man’s back rests against the wall, his hand repeatedly stroking the dog that’s lying flat beside him.

The man’s dirt-stained jeans are torn and fraying at the knees.

The dog is a small crossbreed that must include some sort of terrier DNA. Its brown eyes look at me, without any movement of its head.

There’s a presence around the man, more than in his brown-shaded aura, that says he’s given up hope of being anywhere else but on the street.

Three takeaway coffee cups stand beside the dog. I presume they’re empty and probably left there to say he doesn’t want gifts of coffee, just money. But money for what? He needs to feed the dog as well as himself and most hostels will not feed the dog.

I have change in my pocket, left over from buying a coffee at Paddington Station.

The dog’s gaze follows my approach.

I hold out the coins even though the man hasn’t asked for money.

He looks at me; the bit of his face I can see between hair and beard is tanned, leathery skin, tainted by a difficult life spent mostly outdoors.

A shaky hand lifts, palm open, outstretched. ‘Thanks.’ A Special Brew beer can is tucked beside his hip; it is hidden when his arm lowers.

‘You’re welcome. Do you always sit here?’

‘Unless the police move me on.’ His fingers have fisted around the precious coins.

‘Were you here the day a woman fell from the car park a few weeks ago?’

‘No, love. I never saw anythin’. Did you know ’er? Don’t y’u think the police did their job?’

‘I – I just wondered.’

‘Well, I never saw ’er. I wasn’t ’ere at the time.’

‘Okay. Thank you anyway.’ I walk on because there’s nothing else to say.

The air in the side entrance for the car park smells of mildew. I grip the cold metal handrail, which is covered in peeling green paint, and climb the steps. The doors into the parking floors have blue paint that is scarred by numerous initials carved into the wood. Just above the door to the second floor the smell of stale urine taints the air.

The steps are made of bare concrete and the outer wall is constructed with green-painted metal bars that I can see between. The man in the alley is sifting through the coins.

Did Louise climb these steps that day?

The higher I climb, the more I have a sense of her in my chest.

My heart, her heart, is racing with that heavy pulse that I can’t ignore. Listen. Listen. Listen.

I know she wants to tell me something, or persuade me to tell someone else something.

At the top I push the scarred blue door wide and step out on the top floor. I expect to walk into sunshine, but the horizon is grey now.

There are about a dozen cars sprinkled across the space but no one else is up here.

What a place to die. Why was Louise here? Was she alone?

A full rainbow appears, arching over the buildings on the other side of the town.

The side of the car park that hangs over the shops slightly is only a few metres away from the stairwell. The shop Louise fell in front of is under the corner there.

I try to hear Louise’s voice as I walk to the corner where I know she stood. But I can’t make out any words. ‘What happened?’

Beyond the rainbow, the horizon is blurred by the rainstorm.

The wall is bare, rough concrete, like the rest of the car park. I imagined the wall would be waist-high but the top of the wall is chest height.

Louise could not have fallen accidentally; she must have been picked up, or climbed up.

My elbows rest on the wall as I look down. Even on my toes I can only just see the shops on the far side of the pedestrian area.

A breeze tosses the hair away from my face and makes it dance as the air sweeps up from below.

I want to see what Louise would have seen that day. I feel as though I should know why she was here. I’m hoping that being here will increase the connection I have with her. I look for images in my memory, memories that are not mine, but I can’t find them.

My hands press on the wall and I scrape the toes of my trainers as I scramble and pull myself up. The rough concrete catches at strands of the fine wool in my jumper and scuffs my jeans while I manoeuvre my legs so I can sit on the wall with a leg dangling either side.

The area below is flooded with people walking into the town centre.

I have never been afraid of heights. Living with a weak heart that threatened to kill me any day meant nothing else scared me as a child. I was always reckless and careless, rather than cautious. I was either in hospital or pushing the boundaries and packing in as much enjoyment as possible before the next time.

But my periods of enjoyment were manic. Out of control at times, as I tried to fill up the vacuum in me. I was scared and lonely for large parts of my life, even with Simon as a surrogate father, in his school and college days. He was so much older and there were times when I wanted him, and he wasn’t in reach.

What about Louise? Was she scared that day?

Surely someone must have been here with her? The wall is too high for it to have been an accident. Someone must know how she fell.

I look down and see a vivid image of her broken body lying on the pavement. Louise would have realised she was falling and, in the next moment, hit the ground.

I look up at the rainbow and the haze of the rain in the distance.

The only reason Louise would have been here alone was if she had chosen to fall. Which means this heart must have been unbearably sad. But I know sadness can drag people down into the strong undercurrents of a black, thrashing sea.

The rainbow is brighter now, defying the dark grey behind it. I don’t want to think of Louise broken on the floor down there. ‘I will think of the hope you are giving me.’ Even though I can’t hear her, perhaps she can hear me, and she must know how grateful I am.

The wooden skateboard scrapes on the metal of the cycle rack, pulling my gaze down to the youth practising his tricks.

I see a free runner when I look back at the tops of the high buildings; I see bravery and body strength to balance, watching an imaginary me jump along the tops of the buildings. Me. A Marvel superhero making this world mine. If I weren’t ill, I might have become someone with that much freedom. Not a superhero, obviously. But unrestrained. That was the good thing about my bipolar: it made me vibrant at times, capable of anything.

I will not be a free runner now, but Louise’s gift means I will be able to do other things to set this heart on fire with adrenalin.

The colours of the rainbow fade.

A girl’s laugh rises from somewhere in the lower levels of the car park and a mother’s sing-song voice responds.

A child – that is what I want to set this heart on fire. I just want to fill this heart with love. To fill the hole in me.

A sadness that is overwhelming pushes through my chest, forcing its way in. I think it is Louise’s sadness. I don’t feel sad.

Perhaps I have made her think about her children. They’re orphans now. Like me. But not like me, because they have grandparents.

‘Why were you here, Louise?’ The words are swept away on the breeze, without answer. She had parents who loved her, and children.

‘How did you fall? You can’t have wanted to leave your children.’

The long grey smudge of rain is moving past Swindon, along the outskirts, over the distant hills, blown by the wind higher up in the atmosphere.

I swing my leg over and drop down onto the tarmac.

There is somewhere else I want to go before I catch the train back to London.

There’s space on a park bench next to a young woman. I perch on the edge because there’s a missing piece of wood in the seat.

The heels of my shoes tap a quick beat on the pavement. It is a nervous habit that I have had for as long as I remember – ‘You have a twitchy leg,’ Simon used to say when we were sitting in waiting areas for whoever would collect us next.

There is dust from the wall on my jeans. I brush it off.

The woman is looking at two young boys who are feeding the ducks. A swan is hissing at the boys to persuade them to drop their bread. They throw the bread into the lake and run to the woman beside me, shouting at the swan, ‘Go away.’

There’s a picture of the blond children feeding ducks in this park. Perhaps Louise walked along this path to reach the car park?

Perhaps Robert and Pat walk here with the children.

Louise tells me that they do, without words; it is just a knowledge that I seem to have always had. I look along the path as if I’ll see them. She wants me to see them.

The path wraps around one edge of the lake.

They’re not here.

On the other side of the park there’s a grass area where they might be. I can’t leave the park without looking.

I get up and walk around to look.

They’re not there.

On the way to the railway station, thoughts spin in my head. They distort and jump like a vintage LP. Louise could not have fallen accidentally. But why would she have chosen to die when she had children who love her?

Was it murder?

Are the police investigating her death?

I stand on the station platform, looking along the track for the train to appear, with one question in my mind, which escapes my lips. ‘Do I have your heart for a reason?’ I want her to answer. ‘Tell me.’

I won’t know unless she answers.

Was I chosen or found?

Pump-pump.

Pump-pump.

The same banging but no answers.

Why won’t she put the answer in my mind?

‘Did you leave a space for me to take?’ Is that it?

She has nothing to say about her death, so is she looking for me to step in and fill the gap she’s left in the children’s and her parents’ lives?

Chapter 11

21.35.

‘Are you decent?’ Simon’s call resonates through the bedroom door.

‘Yes.’

The door opens in a hesitant way that says he has come to be a father, not a brother.

I smile as I say, ‘Yes,’ again, in a tone that adds, go on, then, speak up. I move my leg so he can sit on the edge of the bed.

He holds out the stack of medicine packets. I left them on the kitchen work surface. I should’ve put them in the cupboard away from the boys.