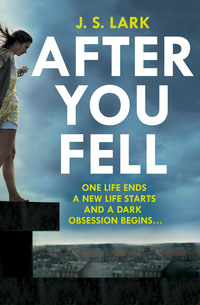

After You Fell

When I walk through the back door into the kitchen, Mim is straining the water from a saucepan of peas.

She glances over her shoulder. ‘Hello.’

‘Hello.’

‘Did you have a good afternoon?’ She puts the saucepan down, but there’s an odd stiffness in the movement that hints at the fact she feels uncomfortable.

I smile, slightly. ‘Yes. Thank you. Can I do anything?’ Maybe it’s because I could do more to help, and she’s fed up of me being as much work as a child. I should help with the cooking and looking after the boys now that I can. I’ve taken more than my share of Simon’s concern and money over the years. The boys are in a play club all day at the moment until the school holidays end but perhaps I could entertain them in the evening and put them to bed. It would be nice to join in with the children’s bedtime routine – be the one to read their goodnight story.

‘Everything’s done, I’m just dishing up. But you can call the boys and Simon and tell the boys to wash their hands.’

‘Kevin. Liam. Simon,’ I shout as I walk across the room, directing my voice through the door on the far side.

Simon leans his head around the door frame within a second, holding onto the frame on the far side. ‘No need to shout, we’re here.’ His words are punctuated with a grin.

‘The boys need to wash their hands.’

‘They’ve already gone to do it. They smelled the sausages.’

An emotional urge that’s not a thought-out decision makes me walk towards him. He knows why without me speaking. He lifts his arms, waiting for me to wrap my arms around his middle and hold on. This is the black hole speaking.

His arms fall onto my shoulders to embrace me and he presses a kiss on my temple. Then he lets go and moves on, talking to Mim as he walks around me.

This is his life. His family. I want my own. That’s all I want to do with this new heart. I don’t want a job. I want a family.

A cry, or something more like a wail, a scream of longing, rips through my head. It is the loudest sound that I have heard in Louise’s voice.

The anger in her impatience is making her spirit stronger.

My hands slide into the back pockets of my jeans, restraining the thoughts in my head, to stop them from slipping out of my mouth. I see Louise’s children in my mind, not her memories, but images of them from the pictures on Robert Dowling’s Facebook page.

Simon would call my thoughts abnormal. He would say I shouldn’t let myself become emotionally attached to the children of the woman I think donated my heart. But I can’t help myself. I already am.

It feels right.

That I have her heart.

That I know where her children are.

That I know where her parents are.

But without being able to understand what it feels like to have a sixth sense, to feel Louise’s emotions, Simon, like Chloe, will think I am going mad.

Since I was sectioned and diagnosed at fourteen, Simon’s favourite phrase has been, ‘You do not have a sixth sense, you have bipolar.’ He’s never believed.

It’s better that I don’t tell him or Chloe anything.

It’s better to lie.

I won’t be able to get closer to Louise’s family if I tell the truth.

‘Have you heard about that job today, Helen?’ Simon asks when we are sitting around the dinner table.

‘I didn’t get it.’ I accept a plate of sausages, mashed potatoes, peas and dark thick gravy from Mim.

‘Why?’ Simon says. ‘Not that I’m complaining about that.’ He takes his plate.

‘I didn’t ask why, but I think working with a class of primary school children might be too much for a little while anyway. I’m well enough to look after a couple of children so I think I’m going to look for a nanny job instead.’

Simon’s lips purse as he picks up his knife and fork, his eyebrows quirking in that paternal expression.

‘What’s wrong with that?’

‘Simon,’ Mim protests, on my behalf. Or perhaps hers, if she wants me out of their house.

‘Nothing. Not really. I agree it’s a better idea to take that step first. I just don’t like the thought of you living with strangers …’

‘I didn’t say I would live in. Although it would be good if I could.’ My heart claps its hands and taps its heels at the idea of living in. Because I do not want to be anybody’s nanny, I want to be Alex Lovett’s nanny. I want to look after Louise’s children, and if I can live in the house …

My heartbeat skips.

Chapter 15

7 weeks and 3 days after the fall.

The coffee inside the takeaway cup resting on my knee is cold. I’ve been sitting on this old iron park bench for nearly two hours.

I’ll have to go soon. Simon and Mim will be back from her parents’ in three hours. Simon will question me if I get home too long after them. He expects me to be there when they walk through the door.

The only movement in the house on the far side of the park has been a single view of the nanny; she walked past a window on the right-hand side on the first floor. I haven’t seen anyone else. Sitting here has shown me nothing. But I’m closer to the children and my heart feels happier.

I think there’s an entrance to the cellar of Alex Lovett’s house on the other side of the park. A door cuts through the wall beneath the iron railing that’s topped by the Fleur de Lys. The ground of the park drops into a ditch that is more than a metre below the street level, and there’s a row of short doors in the wall supporting the street; one for each house. Those doors were probably used for deliveries for things like coal, blocks of ice or bags of flour years ago. Today, though, they must still provide access, through a tunnel under the road, to the basement floor of the houses.

I stand, only because my bottom and legs are numb from sitting here so long. I walk to the left, because when I turn at the corner I’ll be able to look at the house for the longest period of time.

There’s so little activity in the house, I think Alex has taken the children out.

It is Saturday.

I throw the cup of cold coffee in a rubbish bin.

Frustration grips as a pain in my stomach again – right in the middle of me. I want to see the children. The frustration starts to bubble, like fizz rising in lemonade, but it feels as if in a moment it is going to boil like water that tries to jump out of a saucepan.

They are my children, a voice says – a voice that might be Louise’s.

She’s frustrated too.

I walk across the park in the direction of the house, listening again for Louise’s voice, but nothing else is said.

A knocker rattles, announcing that a door is opening. Conversation tumbles into the street.

It is Alex Lovett’s front door. Children’s voices carry on the air and they come out into the street.

I walk down the slope, into the valley at the edge of the park, towards the wall, towards the house.

‘Granny,’ the boy says, looking at a woman I do not know. She’s past middle age. There’s an older man with the children too. I haven’t seen either adult in Facebook posts.

I guess they’re Alex’s parents.

The door closes without an appearance from Alex.

It is less than two months since Louise died.

They need their father.

Their mother.

He should be with the children.

I walk up to the railing, and hold the bottom of the metal rails, watching from my rat’s-eye-view, as they walk off along the street.

Chapter 16

7 weeks and 6 days after the fall.

The edge of the plastic lid scratches my lip, then the coffee burns the roof of my mouth. I move the cup away, flinching.

I am trying to look like a casual occupant of the park bench.

Day by day I am claiming this bench as mine.

It is the perfect place to watch Alex’s house from.

He usually leaves the house at 8.20 to walk the boy to a holiday club. I followed them the first day I’d come here early, but I can’t follow them every day because it will be too obvious. He holds the girl’s hand but the boy keeps a little distant and tucks his thumbs inside the shoulder straps of his backpack denying any chance of contact with his father.

Alex returns at 8.50, with his daughter. They go back inside the house and then at 9.00 the door opens again, and he comes out with keys rattling in his hand as he either walks off down the street or goes to a large Range Rover.

I do not know what time he comes home after work. It is too late for me to stay and watch.

The door opens now, following the same routine.

I put the cup up against my lip and hold up my phone as though I am looking at the screen and look beyond it.

The curls in Alex’s hair are disordered, untidy in a way that suggests his hair has not seen a comb or had a cut for weeks. He’s not shaven either and the growth of blond hair on his chin denies any thought of grooming. The shirt he’s wearing is rumpled.

Watching him is fascinating, like studying an animal. I hear David Attenborough narrating the family’s movements in my head.

I need to understand Alex’s life if I’m going to work out a way to become a part of the children’s lives. I need to spot a weakness – a door that’s been accidentally left open, that I’ll be able to push my way through.

The girl holds onto his hand, which hangs loose. Alex looks back into the house and calls for the boy, who squeezes past his dad and sister and runs ahead.

Louise’s heart pulses with a rush of emotion every day when I see them come out through the door.

‘Wait for us!’ Alex’s call stretches across the park that contains me and two people with their dogs.

His aura’s strange. I have never seen anything so dark before; it is greys, black in places, like a terrible storm wrapping about him.

Alex and the children disappear around a corner.

I drink the cooling coffee and look through Robert Dowling’s pictures on Facebook while I wait.

My life is now paused and played on Alex’s command.

It’s cold today; my free hand slides into the pocket of my coat. There are several used train tickets and the one I need to get home in my pocket. The price of a ticket is extortionate at this time of day.

I have savings: a lump sum put away when Dan told me to get out of the flat; a pay-off for all the jointly purchased white goods and furniture I left behind, and the half of the deposit I lost. But I can’t afford to travel backwards and forwards to Bath every day for long.

You are getting obsessed, Simon’s voice whispers through my head.

I can become an addict of anything, because of bipolar. It is like a gambling addiction, or drug abuse – I can’t stop once I have started believing something. My mind becomes fixated.

This is strange, Chloe’s voice tells me.

It is strange. I know it is. But being given someone else’s heart is strange, especially when that woman steps into your body and tells you to find her family. But this is real. And the house is the jigsaw puzzle that’s waiting for me to step into place and complete it.

I owe this to Louise and I want it for me.

The distant sound of conversation pulls my attention back to the corner that Alex and his daughter appear from. She is half running, taking four or five steps with her short legs compared to his two strides. He’s rushing today.

He opens the front door of his house with the key, but doesn’t close the door after he’s taken the girl inside. Then after a moment of some sort of exchange behind the half-closed door he reappears.

When he walks away from the door the headlights of the Range Rover flash as the car doors unlock.

I wait until he’s in the car and pulling away from the kerb, then stand.

Once he’s gone I usually go somewhere to eat breakfast. Then I come back.

There’s the rattle of a doorknocker that has a looser sound than anyone else’s. I look back to see the front wheels of a pushchair appear from Alex’s house.

The third child will be in that pushchair.

I have only seen the youngest child in a few of Robert Dowling’s pictures.

The nanny steers the pushchair over the threshold, then looks back and says something to the girl who follows.

I think the girl is three years old. She captures my attention more than the others. She’s so small and pretty. I have always wanted a girl and she’s my dream child. My hands want to reach out for her every time I see her. That’s Louise’s desire too, but I know my own feelings are the same, not just hers.

I feel as if Louise would simply pick the children up and run.

I can’t do that; I would not be able to keep them. And I want to keep them. I want to make them mine.

The girl holds onto the pushchair as the nanny locks the door.

The nanny turns the pushchair in my direction, to cross the street.

For the second time, someone is looking at me looking at them.

Perhaps she’s come out of the house to investigate me – the strange woman who has started sitting in the park every day, staring at their windows.

The little girl speaks and the nanny looks down.

A dummy rolls across the tarmac. The little girl picks it up and holds it out. They are in the middle of the street. The noise of the traffic on the busy road behind me feels like a threat but they are in a street with a dead end; the traffic is not near her.

The nanny takes the dummy, wipes it on her top then gives the dummy back to the child.

I am not OCD about cleanliness but I am qualified to look after children and the five-second rule doesn’t apply to children who have barely started developing their immunity.

I start walking as the nanny tips the buggy back so it can get over the kerb on this side of the street. Called into action by her ineptitude.

Louise and I are on the same page. I may not want to take the children, but I want to get rid of that nanny. The children need me; Louise and I know that.

People who do not look after children properly do not deserve to have them.

They walk along the path on the other side of the park’s railing.

I walk in the same direction, towards the park’s exit.

The woman looks to be in her late teens or early twenties. Too young.

The small girl is on the far side of the pushchair so I can’t see her.

I want to see her.

I walk quicker to get ahead of them. I can see the girl’s expression is compliant as she looks at the pavement, silent.

The colours in her aura have faded, as sadness dances around her. Children often have splashes of colour, not layers. She has a cloud that is blended to a point it is hard to pick out the different shades.

The girl’s sadness lances through me, cutting into the flesh of my heart with a quick thrust. Things are not right in that house.

I want to help the children. I know what it is like to grow up without a mother. They must be feeling broken. Black holes will be forming, stealing all their happiness.

They need me.

I am so glad you brought me here, Louise. Thank you. I know you are right.

The park’s exit is at the tip of its triangle shape. The path I am walking on and the path they are walking on brings us closer.

The nanny looks at the main road.

I pretend to look at my phone as I walk, and laugh, as though I have seen something funny, then lift the phone to aim the camera. Tap. Tap. Tap. It will not be the best picture, the nanny is side on, but it is something for me to use to help me find her on social media.

The distance between us becomes a few paces.

I grip one of the fleur-de-lys at the corner of the iron railing for a second as I walk out while she takes the last few steps. I think she’s going to walk on along the pavement, so I wait, to let her pass, but she turns the pushchair into the park.

An intense urge begs me to bend down and touch the little girl’s head. To run my fingers through her curls. To touch her shoulder, reach for her hand and help her run. But all I do is smile at the woman I hate and step out of the way.

She walks past me with no acknowledgement as though I am nothing.

I think she’s going to the playground in the farthest corner of the park.

I want to walk along the path by the railing, so I can keep watching them. But that would be too obvious.

I press the button for the pedestrian crossing, stop the traffic and walk away.

I turn the key and open Simon and Mim’s door long before they will be home. Simon will not know I have been out today.

When Simon comes in the back door, I am lifting a fish pie with a golden, crispy mashed-potato top out of the oven. A steamy smoked-cod smell fills the room. I made the pie before Mim got home with the boys and I’m proud of it. No one would call me a cook. Dan and I lived on ready meals, but that was out of necessity in the last years of my incapability. This pie is a triumph over a fate that tried to kill me.

Louise changed that fate.

Perhaps she was a good cook?

I know that today has spurred me into wanting to play happy families with her children. All I can think about is looking after them. My head is running through the images of my life with them. They are not Louise’s memories, they’re my hopes.

Simon smiles at me as I straighten up, put the hot dish on top of the oven and push the oven door shut with my toes.

His gaze moves to Mim and the boys, who are sitting around the table. ‘Hello,’ he says as the boys scramble to say good evening, their chairs scraping on the floor.

Their arms wrap around his legs.

I see Louise’s children greeting me like that.

He slides the rucksack he uses for work off his shoulder and unzips it, looking at me again and deploying the grin the boys have inherited from him.

He pulls a magazine out of his bag and holds it out. ‘For you.’

A copy of The Lady hovers in front of me.

I pull off the blue striped oven mitts and drop them down beside the pie dish.

‘I agree.’ His voice lifts with conviction. ‘You should find a nanny job, but you don’t have to take one that will be too much hard work. If you are going to get a job go for the best position, somewhere they will not expect you to do the cleaning and the cooking too.’

I take the magazine.

But I do not want to be anyone’s nanny. I want to be Alex Lovett’s nanny.

I just need to get rid of the useless girl he has now.

Chapter 17

9 weeks and 4 days after the fall.

My hand is in my jeans pocket gripping the key for the front door of the house I rent a room in.

The church bells are ringing from two different directions but otherwise the streets are quiet.

There’s something unique about the city of Bath. Perhaps it’s because the city centre is so much smaller than London and the size develops a sense of intimacy.

I run slightly, in a jog, along the pavement of the last street until the point it meets the main road, then I slow to a walk.

The excitement is buzzing in my ears. Fizzing words and thoughts through my head. I can’t believe I am here. Out in the world on my own and focusing on a future that I can see clearly. I just need to work out how to get from this to that. I have spent all night trying to think of a plan.

But with Louise’s help, I will come up with a way. I’ll get into the house somehow.

It is the first time I have come here on a Sunday. Only a couple of cars pass by on the main road.

Most people are still in bed, eating breakfast, drinking coffee and reading papers.

Jive music tumbles out from the old railway station near the crossing that is now used as an antique market. The music calls to the few of us who have risen early, pulling passers-by inside. I am not drawn.

The railing-imprisoned park is opposite.

I ought to have a reason to sit in there, though. I haven’t bought a coffee yet. I rushed, because I was so glad to be able to walk out of a door and come straight here.

I turn back towards the music and the open door. There will be somewhere inside that sells takeaway coffee.

The small door leading into the under-cover market is deceptive; inside it is a huge space with a towering vaulted glass ceiling, held in place by a backbone of wrought-iron arches.

The scattering of antiques stalls is belittled by the architecture and there are scarce customers; it is mainly the stallholders talking to each other as they eat rolls bursting with bacon.

A freshly ground coffee aroma wafts from the far end where the stallholders must have bought their rolls.

When I leave the market the coffee in the cup is so hot it burns my hand through the insulated cardboard. I cross the road, hurry into the park and rush for my bench, then put the cup down on the seat beside me, claiming the bench.

All the pressure and excitement of the last few days slips away on my outbreath.

I have lied so many times to Simon and Chloe my mythical life is a tangled ball of yarn that could unravel at any moment. They think I start a job here on Monday, but I have been vague about the family and the address so they can never try to find where they think I work.

I don’t like having so many secrets between me and them, but Louise and her family come first now. They must come first. This is a place that’s been prepared for me. She’s chosen me to fill the gap in her family, to love her children.

This is my job.

I am starting to feel as if the reason for my life since birth was to be ready to fill her space. Left alone by my parents so that I would want hers. Born with a faulty heart so that I would need hers. Prevented from having children so that I can love hers.

But I know that can’t be true.

I am renting a room in a woman’s house. I spotted it for rent only a few streets away on SpareRoom and rushed to move because I didn’t want to lose the chance.

I have moved to Bath, and I am going to sit here and live on the last of my savings until I find a way to be with the children.

I am due to meet Alex in just over a week, for the fake appointment. I’ll need to create more lies then. But I am becoming a very good liar, with Louise as my cheerleader, pushing all these shameless tall tales out of my lips. But if lying means I can have what I want, I am happy to lie.

The rungs of the chilly metal seat press into the backs of my thighs. The cold creeping through my jeans.

I take my phone out of my back pocket but I don’t look at it, I look in through the first-floor windows of Alex’s house. Into his living room.

I came last night and saw Alex walk across the room when there was a light on. I couldn’t see very much, but I saw enough to know it’s the living room.

If Alex or the nanny see me, I imagine they barely notice me. I am probably just the woman who sits in the park.

The phone shivers in my hand. The single vibration of a message from Chloe.

‘Good morning. What’s life like in Bath?’

‘Nice. Laid-back.’ I reply via WhatsApp.

‘At least you’re only a short train journey away. If you’d moved farther away I would have hated you.’

‘I promise we’ll see each other—’ my thumb stops, hesitating over the letters when I hear the familiar rattle of a doorknocker ‘—often,’ I type and send without looking back down.

I leave the phone resting in my lap and take a sip of coffee that scalds my tongue.

A woman with long pitch-black hair has stepped out of the house and turned back to face Alex, who is standing in the doorway.

She’s wearing a sequin-covered black mini dress and high heels – nothing else. No jumper. No coat.

The sequins catch the sunlight. She wobbles slightly, balancing on killer thin black patent stilettos. She’s gripping a small evening bag with both hands.